GARYSLUDDEN/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

GARYSLUDDEN/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Meeting Patients’ Pain Management Needs

Mastering the art of dental anesthesia helps support the highest levels of patient-centered care.

Oral health professionals who put patient-centered care first may find the “art of anesthesia” to be a straightforward concept. Patient-centered care seeks to deliver therapy that is humane and characterized by good communication and shared decision-making—thus, the focus is person-centered.1 The Commission on Dental Accreditation standards emphasize the importance of educational processes and goals for comprehensive patient care, and encourage patient-centered approaches in teaching and oral healthcare delivery. All team members involved in the delivery of care are expected to develop and implement practices, operations, and evaluation methods so that comprehensive, patient-centered care is the norm.

Furthermore, the concept considers patient needs, training of allied personnel, and evaluating practice and outcomes to improve the quality and efficiency of care.2 Practitioners striving to master the art of anesthesia are in alignment with these standards.

Providers who implement this concept tend not to rely on novel approaches or popular opinion (such as found on social media), but instead go back to the foundational knowledge to help them understand what best meets the patient’s needs. Effective pain management in patient-centered care requires thoughtful reflection of the various components that comprise the process, and assessment of whether the clinician’s current approach truly meets today’s standard of practice.

ANESTHETIC DELIVERY EXPERIENCE

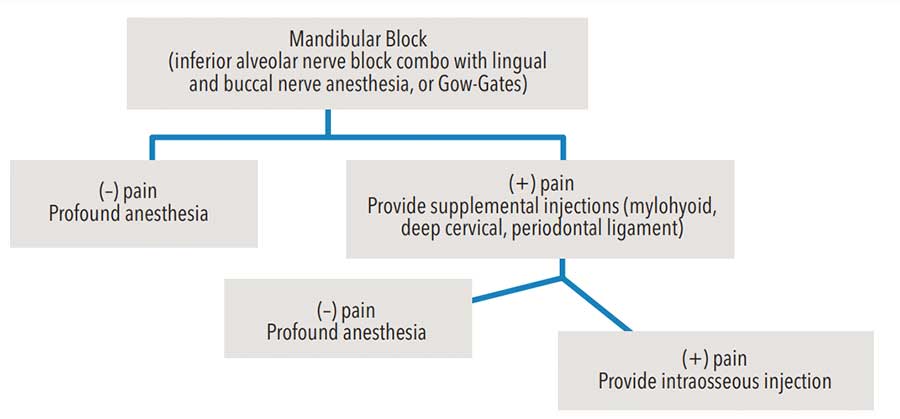

Proficiency in local anesthetic injections can be learned in part through education and literature, but experience is equally important. Techniques and algorithms of clinical recommendations are also available to help advance oral health professionals’ understanding of the science and enhance their skill sets.3,4 For example, a mandibular molar presenting with symptoms of irreversible pulpitis would greatly benefit from a mandibular block injection, followed with supplemental techniques, such as buccal/lingual infiltrations and an intraligament/periodontal ligament injection, as well as further intraosseous administration (Figure 1).4

Consistently successful injections are rooted in a thorough understanding of the patient’s anatomy. Gently palpating the landmarks to prepare for the injection is good practice to gauge the area best suited for needle insertion. A panoramic radiograph may also affirm the best injection technique for a specific patient.5 Additionally, palpation familiarizes the provider with any atypical features. This includes recognizing a flared mandible, which dictates the starting position for a mandibular block injection. Gently wiping a 2×2-inch gauze over the injection site initiates the placement of topical anesthetic prior to the injection.3 Maintaining taut tissue is an important factor in ensuring comfortable needle insertion.6 The application of a topical anesthetic prior to injection may be helpful in sensitive patients. Furthermore, speed of anesthetic delivery is a key component that speaks to a clinician’s expertise and mindfulness of patient comfort.7

TWO-WAY COMMUNICATION

One of the most crucial aspects of mastering effective, individually tailored pain management is the ability to clearly communicate with patients. Oral health professionals who are transparent in their explanations and build trust with patients tend to receive word-of-mouth referrals.8–10 In addition, children and some patients with special needs tend to respond better to treatment when the operator uses a “tell-show-do” approach.11 Patients may also feel more comfortable with clinicians who speak their language and fully explain all aspects of the treatment plan.12,13

Listening is a form of communication that is often overlooked in clinical practice. Acknowledging and listening to the concerns of patients are great practice-builders, as they demonstrate the clinician is genuinely interested in patient-centered care. Patients not only favor providers who take the time to listen, good communication also supports effective patient education and collaboration in treatment decisions.14

While effective communication with patients can be challenging at times, understanding how the patient receives the recommendation for treatment will enhance the success of any care plan. There is an aspect of empathetic listening that needs to occur between the provider and patient to prepare the patient for any upcoming invasive treatment. The oral health professional has the training to choose the appropriate technique and anesthetic agent for treatment,15 and with empathetic listening, this can become a collaborative effort that helps make the patient more comfortable during the provision of care.14,16

PAIN MANAGEMENT ARMAMENTARIUM

Devices in the dental marketplace are evolving to aid in the overall delivery and experience of local anesthesia. Many of the advances are focused on reducing pain and achieving more profound results.17 One example is computer-controlled local anesthetic delivery, an automated technology that controls the deposition rate to slowly administer the anesthetic agent for improved patient comfort during the injection.

Again underscoring the importance of effective two-way communication, a patient may state in the initial conversations that he or she is “allergic” to epinephrine. After reviewing the comprehensive medical history, the oral health professional should educate the patient regarding true allergies to epinephrine, and be willing to spend time informing the patient about the benefits of a vasoconstrictor. This should include details about the longer duration of anesthesia and reduced risk of toxicity of the anesthetic while present in the patient’s system.18

Patients sometimes complain of heart palpitations that may arise when an anesthetic containing epinephrine is used for an injection. Prudent providers may decide to use a plain anesthetic agent for these patients or in cases in which the individual is classified as ASA III under the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) Physical Status Classification System.19

Other innovations in pain management acknowledge patients’ desires to reverse the feeling of numbness20 after a procedure and suggest which anesthetic agents are optional for analgesia.21 While there is great benefit to having multiple options and tools in the pain management armamentarium, the art of dental anesthesia is grounded in simplicity.

EVER-EVOLVING OPTIONS

The following is an example of how clinicians can combine communication and supplemental drug options for anesthetic management in the delivery of patient-centered care. For the patient who wants to return to work at normal capacity (ie, no feeling of numbness or speech dysfunction), phentolamine mesylate (PM) has been studied to help in the reversal of soft tissue anesthesia.20 In both adult and pediatric patients, PM is delivered toward the end of the appointment, with the understanding the patient will begin to return to normal feeling 30 minutes to 60 minutes sooner than the intended length of anesthetic duration. According to the manufacturer, PM is a vasodilator and should be given in a 1:1 ratio in comparison to the original anesthetic that was delivered at the beginning of the appointment.22 For instance, if 1.7 ml of anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor was delivered in a Gow-Gates injection, the same technique and amount of PM needs to be delivered at the deposition site. Communication with the patient is suggested to advise of possible soreness from two injections delivered at the same location during the appointment.

Local anesthetics are more profound when the lipid solubility of tissue is present and the tissue is healthy. Anesthetics are generally acidic, but when mixed with careful calculations of sodium bicarbonate, the anesthetic becomes more neutral for delivery into tissue. Many studies have been conducted to determine the results of buffering anesthesia. A recent meta-analysis reported that buffered anesthesia is more effective than nonbuffered agents for dental procedures.23 The authors noted the high success of buffered anesthetic in anterior maxillary teeth, and a 20% to 56% success rate in teeth with irreversible pulpitis in the mandible after receiving a block injection.

CLINICAL CHALLENGES

When a patient claims “it is hard to get me numb,” oral health professional may want to consider using higher-concentration anesthetics or changing their technique combination in order to achieve profound anesthesia. Before considering additional or alternative techniques, however, it is essential to first determine if the case is appropriate for a specific injection technique being considered.

A comprehensive medical and dental history will identify if the patient has history of orthognathic surgery or trauma affecting the position of the condyle or compromising the deposition site of the injection. For example, when delivering a Gow-Gates block, a patient having difficulty with maximum opening and unable to have a bite block comfortably placed on the contralateral side may not experience profound results from this specific block technique. For pediatric and adolescent patients especially, the importance of palpating and understanding the anatomy of the patient are crucial to the success of the injection.24

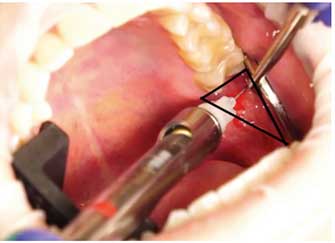

Reviewing anatomy is essential when attempting an injection other than the traditional inferior alveolar nerve block. To review the specifics of a profound injection technique, consider providing a Gow-Gates block. Clinicians should review the anatomical landmarks for this injection, which outline a reverse triangle.25 Using a Gow-Gates injection block has a 90% success rate in anesthetizing the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (Figure 2).26–28 With 1.8 ml of anesthetic delivered 1 mm from the neck of the mandibular condyle, the anesthetized nerves include the inferior alveolar and lingual, and sometimes buccal, auriculotemporal, and mylohyoid. Clinicians should consider following up with a supplemental infiltration injection using a 4% articaine HCl 1:100,000 epinephrine solution to help achieve more profound anesthesia.29

CONCLUSION

As a care delivery concept, mastering the art of dental anesthesia is achievable and essential for effective patient-centered care. Practitioners should strive for clear communication and empathetic listening, as these will support collaboration with patients during treatment planning and therapy. Together with expert knowledge of anatomy, slow delivery, mindfulness, and evidence-based decision making, selecting appropriate and case-specific techniques and anesthetics will help clinicians provide the best care possible. When established through repetition, this clinical approach will allow providers to deliver consistently effective pain management and optimal treatment outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Scambler S, Delgado M, Asimakopoulou K. Defining patient-centred care in dentistry? A systematic review of the dental literature. Br Dent J. 2016;221:477–484.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Current Accreditation Standard. Available at: ada.org/en/coda/current-accreditation-standards. Accessed February 8, 2021.

- Ogle OE, Mahjoubi G. Local anesthesia: agents, techniques, and complications. Dental Clin North Am. 2012;56:133–148.

- Reader A, Nusstein J, Drum M. Successful Local Anesthesia for Restorative Dentistry and Endodontics. Batavia, Ilinois: Quintessence Publishing; 2011:120–129.

- Afsar A, Haas DA, Rossouw PE, Wood RE. Radiographic localization of mandibular anesthesia landmarks. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:234–241.

- David HT, Aminzadeh KK, Kae AH, Radomsky SC. Instrument retraction to avoid needle-stick injuries during intraoral local anesthesia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:e11–e13.

- Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, Corbett IP, Meechan JG. Articaine buccal infiltration enhances the effectiveness of lidocaine inferior alveolar nerve block. Int Endod J. 2009;42:238–246.

- Gremler DD, Gwinner KP. Customer-employee rapport in service relationships. J Service Res. 2000;3:82–104.

- Gremler DD, Gwinner KP, Brown S. Generating positive word-of-mouth communication through customer-employee relationships. Int J Service Industry Manag. 2001;12:44–59.

- Jung YS, Hae‐Young Y, Youn‐Hee C, et al. Factors affecting use of word‐of‐mouth by dental patients. Int Dent J. 2018;68:314–319.

- Allen KD, Stanley RT, McPherson K. Evaluation of behavior management technology dissemination in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 1990;12:79–82.

- Yamalik N. Dentist‐patient relationship and quality care 3. Communication. Int Dent J. 2005;55:254–256.

- Rowland ML. Enhancing communication in dental clinics with linguistically different patients. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:72–80.

- Wener ME, Schönwetter DJ, Mazurat N. Developing new dental communication skills assessment tools by including patients and other stakeholders. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:1527–1541.

- Haas DA. An update on local anesthetics in dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:546–552.

- Jones LM, Huggins TJ. Empathy in the dentist-patient relationship: review and application. NZ Dent J. 2014;110:98–104.

- Malamed SF, Tavana S, Falkel M. Faster onset and more comfortable injection with alkalinized 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013;34(Spec No 1):10–20.

- Rosenberg PH, Veering BT, Urmey WF. Maximum recommended doses of local anesthetics: a multifactorial concept. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:564–575.

- Southerland JH, Gill DG, Gangula PR, Halpern LR, Cardona CY, Mouton CP. Dental management in patients with hypertension: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2016;8:111–120.

- Daubländer M, Liebaug F, Niedeggen G, Theobald K, Kürzinger ML. Effectiveness and safety of phentolamine mesylate in routine dental care. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148:149–156.

- Malamed SF. Local anesthetics: dentistry’s most important drugs, clinical update 2006. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2006;34:971–976.

- Tavares M, Goodson JM, Studen-Pavlovich D, et al. Reversal of soft-tissue local anesthesia with phentolamine mesylate in pediatric patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1095–1104.

- Kattan S, Karabucak B, Korostoff JM, Hunter PS. Do buffered local anesthetics provide more successful anesthesia over non-buffered solutions in patients requiring dental therapy? A systematic review & meta-analysis. Dental Theses. 2017:19.

- Yamada A, Jasstak JT. Clinical evaluation of the Gow-Gates block in children. Anesth Prog. 1981;28:106.

- Wolfe SH. The Wolfe nerve block: a modified high mandibular nerve block. Dentistry Today. 1992;11(5):34–37.

- Wilson S, Johns P, Fuller PM. The inferior alveolar and mylohyoid nerves: an anatomic study and relationship to local anesthesia of the anterior mandibular teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;108:350–352.

- Madan N, Shashidhara Kamath K, Gopinath AL, Yashvanth A, Vaibhav N, Praveen G. A randomized controlled study comparing efficacy of classical and Gow-Gates technique for providing anesthesia during surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molar: a split mouth design. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017;16:186–191.

- Sherman MG. Anesthetic efficacy of the Gow-Gates injection and maxillary infiltration with articaine and lidocaine for irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2008;34:656–659.

- Fan S, Chen WL, Pan CB, et al. Anesthetic efficacy of inferior alveolar nerve block plus buccal infiltration or periodontal ligament injections with articaine in patients with irreversible pulpitis in the mandibular first molar. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:e89–e93.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2021;19(3):16, 18, 21.