Dietary Influence on Inflammation

Consuming a Middle Eastern diet could reduce systemic and periodontal inflammation compared with a Western diet.

This course was published in the January 2018 issue and expires January 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the mechanism of inflammation.

- Identify foods that induce and prevent systemic inflammation.

- Compare the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties of two diets

- Use the government sources of dietary recommendations to provide dietary counseling.

Consuming anti-inflammatory foods has been shown to deter and reduce inflammation in the body.2 Consuming a diet containing fewer pro-inflammatory foods and more anti-inflammatory foods may create less systemic and periodontal inflammation.5 This article presents novel information about how consuming a Middle Eastern diet could reduce systemic and periodontal inflammation. A Middle Eastern diet is eaten by individuals from countries such as Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, Egypt, and Lebanon.

MECHANISMS OF INFLAMMATION

C-reactive proteins (CRP) and cytokines are biomarkers of systemic inflammation. Cytokines include tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFa), interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8. They mediate inflammation by recruiting other inflammatory cells and increasing vascular permeability.4 Cytokines have the ability to initiate bone loss and damage tissues in chronic inflammatory diseases.4 Their role in initiation and progression of periodontitis has been established.

Leukocytes used to fight inflammation produce reactive oxidative species (ROS) that aim to eliminate pathogens during phagocytosis.5 ROS are molecules that contain oxygen, often noted as free radicals.4 ROS destroy cells which then stimulates the production of cytokines, triggering inflammation.5 If antioxidants are present, they can counteract the damage from oxidative stress.5 However, high levels of ROS cannot be mediated by antioxidants alone.5 Antioxidants are substances that can reverse the damaging effects from oxidation.4 Sources of antioxidants include vitamins A, C, and E, curcumin, green tea, red wine, and coffee.5 Recent research is focused on the role antioxidants play in preventing periodontal destruction. Periodontal tissues experience oxidative stress from inflammation.5 Antioxidants scavenge ROS, thus reducing the severity of periodontal inflammation.5

PRO-INFLAMMATORY FOODS

Pro-inflammatory foods trigger or prolong the systemic inflammation. Pro-inflammatory foods include refined carbohydrates, refined sugar, saturated fat, trans fat, most omega-6 fatty acids, some types of alcohol, red meat, and processed meat.1,6

Refined carbohydrates fuel the production of advanced glycation end-products (AGE) that stimulate inflammation.6 AGE production is a part of normal metabolism, but if excess AGE reaches tissues and circulation, it can become pathogenic.7 Refined carbohydrates are also known to create oxidative stress and are linked to higher levels of CRP.8 Excess consumption of refined carbohydrates is also linked to higher levels of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6.4 Refined carbohydrates are found in white flour products, white rice, white potato products (instant mashed potatoes and French fries) and many cereals.6 Table sugar (sucrose) triggers the release of cytokines interleukin-1, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and TNFa.4,6 Higher levels of interleukin-6 and CRP are associated with consumption of red meat, processed grains, refined carbohydrates, and high-fat dairy products.9

THE EFFECTS OF LIPIDS

Lipids affect the body in several ways. Diets rich in saturated fats increase oxidative stress.10 Saturated fats also increase the intensity of and duration of inflammation.10 Saturated fats are found in butter; cream; regular-fat milk and cheese; lard; chicken skin; fatty cuts of beef, pork, and lamb; and processed meats, such as salami and sausage. Trans-unsaturated fatty acids (trans-fats) increase production of cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and TNFa.11 Trans-fats can be found in fried products, processed snack foods, frozen food products, cookies, donuts, crackers, and margarine.8 Excess consumption of omega-6 fatty acids can trigger the body to produce pro-inflammatory chemicals.6 Omega-6 fatty acids are found in vegetable oil, corn oil, sunflower oil, salad dressings, fast food, cookies, cakes, chips, pork, beef, and butter.6,8

Omega-3 fatty acids have an opposite effect compared with omega-6 fatty acids and saturated fats. Omega-3 fatty acids stimulate antibody formation which will help fight infection.10 A 2009 study performed by Micallef et al12 found that increased consumption of omega-3 fatty acids reduces CRP levels. Omega-3 fatty acids are found in canola oil, soybeans, walnuts, chia seeds, flaxseeds, mackerel, salmon, tuna, and sardines.8

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY FOODS

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY FOODS

Foods thought to reduce inflammation are called anti-inflammatory foods. Foods containing vitamins A, C, D, and E have been noted for their ability to reduce systemic inflammation.4 Fruits and vegetables are generally considered healthy food choices. Lower levels of CRP are found in those who consume high amounts of fruits and vegetables on a regular basis.9 Foods containing vitamin A include cod liver oil, carrots, liver, sweet potatoes, broccoli, and leafy vegetables.5 Foods containing vitamin C include oranges, lemons, limes, grapefruits, pineapples, kiwis, blueberries, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, tomatoes, onions, bell peppers, broccoli, collard greens, cabbage, and liver.5,13 Foods containing vitamin D include fish, eggs, mushrooms, liver, and milk.5 Foods containing vitamin E include poultry, pork, olive oil, fish, almonds, sunflower seeds, and cereals.5,13 Because food preparation can inactivate vitamins, consuming raw fruits and vegetables may be beneficial. Green tea and coffee contain phenol, which is an antioxidant.8 Beneficial omega-3 fatty acids are found in canola oil, soybeans, walnuts, pecans, chia seeds, flaxseeds, mackerel, salmon, tuna, and sardines.13 Curcumin is found in the spice turmeric and may also be beneficial.14

DIETARY DIFFERENCES

Foods traditionally eaten in the Middle East are similar to the Mediterranean diet. The Mediterranean diet is known for its anti-inflammatory properties.13 It includes more fresh foods and fewer processed foods.13 Middle Eastern dishes commonly contain spices like dill, garlic, mint, cinnamon, oregano, parsley, pepper, turmeric, cumin, and coriander.15 The Middle Eastern diet is low in refined carbohydrates; rich in omega-3 fatty acids; high in vitamins C, D, and E; and rich in fiber. Table 1 (page 35) lists foods and drinks consumed in a Middle Eastern diet.15,16

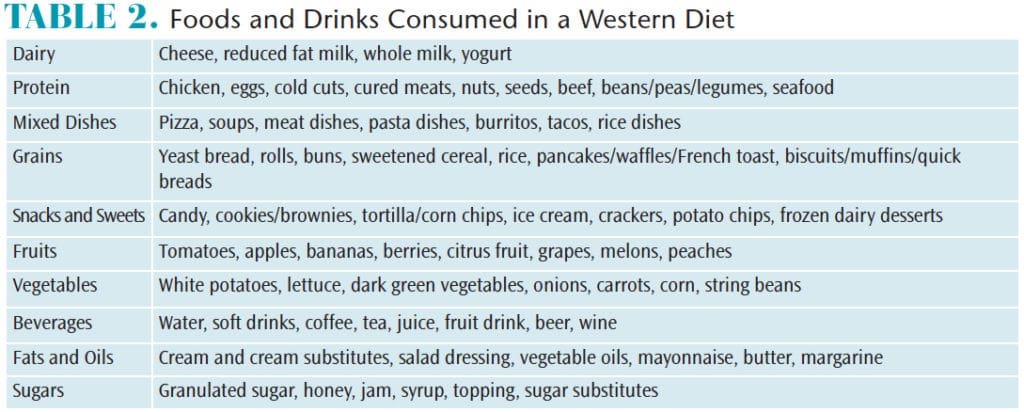

Many foods in the Western diet are highly processed.17 A survey published by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2016 listed the foods that are commonly eaten in the US.18 The items were divided by food groups and the most consumed items are listed first in each category. Table 2 lists the most frequently consumed foods and drinks found in the Western diet.18

At first glance, it appears that the USDA survey indicates that few, if any anti-inflammatory foods are consumed. Anti-inflammatory foods were listed in the survey, but results indicated they were infrequently eaten. The Western diet contains elevated levels of many pro-inflammatory foods, such as processed grains, refined carbohydrates, omega-6 fatty acids, red meat, and high-fat dairy products.8,19

More anti-inflammatory foods are incorporated in the Middle Eastern diet than in the Western diet. The Western diet has a deleterious, higher ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids.8 Fewer nutrients are lost from fruits and vegetables through food preparation in the Middle Eastern diet.

Consuming a Middle Eastern diet may promote less systemic inflammation and periodontal inflammation than the Western diet. A pilot study performed by Woelber et al8 suggested that a diet low in carbohydrates, high in omega-3 fatty acids, rich in vitamins C and D, and high in fiber may reduce gingival and periodontal inflammation. Despite limited science, it is not unreasonable to suggest that switching from a Western diet to a Middle Eastern diet may reduce gingival inflammation.

![]() DIETARY COUNSELING

DIETARY COUNSELING

Providing nutritional advice to patients is within the scope of practice for dental hygienists in the US. The 2016 American Dental Hygienists’ Association Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice indicate that dental hygienists should assess nutrition history and dietary practices of all patients.20 This assessment should be used to determine the patient’s level of risk related to caries, nutritional deficiencies, inflammation, obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and more. While some dental hygienists may not feel dietary counseling is part of their role, the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans suggest that everyone has a role in supporting healthy eating patterns.21 Dental hygienists practicing in the US should become familiar with and provide recommendations to patients based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Dental professionals can provide nutrition assistance tailored to the needs of the patient. Healthy eating patterns should be flexible to accommodate both traditional and cultural foods.21The Dietary Guidelines for Americans include the Healthy Mediterranean-Style Eating Pattern, a modified version of the Mediterranean diet.21 This dietary plan is the Healthy US-Style Pattern modified to include more fruits and seafood and less dairy.21It is not an exact replica of the Mediterranean diet, but one that is a closer match to the dietary recommendations with which Americans are familiar.21 The Healthy US-Style Pattern includes a variety of fruits and vegetables, grains consisting mostly of whole grains, fat-free or low-fat dairy, a variety of protein sources including seafood, lean meat, poultry, eggs, legumes, nuts, seeds, and soy.21 Individuals who follow this dietary plan should consume 2.5 cups of fruits and 2.5 cups of vegetables each day as part of a 2,000-calorie diet.21 It also recommends limiting saturated fats, trans-fats, added sugars, and sodium.21

Dietary counseling may include a discussion of the effect that diet has on systemic inflammation. This is especially helpful for patients who are obese or who are at risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Patients may be guided to healthier options, such as the Mediterranean diet.

When treating a patient with gingival inflammation, anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory foods should be discussed. Provide the patient with examples of each of the foods recommended. Gingival inflammation may be reduced through supplementation with fish oil.22 Periodontal tissues are more likely to heal better after nonsurgical periodontal therapy when fruits and vegetables are consumed regularly.23 For this reason, post-treatment recommendations should include consuming fruits and vegetables each day. Chewing raw fruits and vegetables may stimulate pain during the first few days after nonsurgical periodontal therapy, so juices and smoothies should be considered as an alternate method of incorporating fruits and vegetables.

Even though most dental professionals feel dietary counseling is important, studies suggest that they do not regularly provide nutritional advice to patients.24 Barriers preventing dental professionals from providing dietary counseling include time, patient knowledge of nutrition topics, patient compliance with recommendations, counseling skills, and practitioners’ knowledge of nutrition.24One reason why dental hygienists may not feel prepared to provide dietary counseling is that the level of training in this area may not be consistent among all educational programs.

EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS

There are no educational standards set by accrediting bodies for dietary counseling in dental hygiene education.25 For this reason, the level of training from program to program may differ greatly. One method of ensuring that dental hygienists can provide dietary counseling that meets the goals of Healthy People 2020 initiatives is to incorporate a standardized nutrition model into dental hygiene education programs.25 Healthy People 2020 is an initiative to create healthier American citizens. One of the goals of Healthy People 2020 is to “promote health and reduce chronic disease risk through the consumption of healthful diets and achievement and maintenance of healthy body weights.”26 Objectives of this goal include strategies that can be used by dental hygienists during nutritional counseling.They include increasing the percentage of medical offices who provide nutrition-related education, increasing the intake of fruits and vegetables, and reducing the consumption of calories from trans-fats, saturated fats, and added sugars.26 The baseline data and target data for these objectives are included in the report. The target for each objective is much lower than the recommendations found in the Healthy US-Style Pattern from the Dietary Guidelines mentioned before. These targets can be used as recommendations for patients and become standards for dietary counseling in education programs.

While changing educational standards is beneficial to future dental hygienists, a different approach is needed for those who are already practicing. State-level continuing education requirements for dental professionals could require a course in a nutrition-related topic each renewal cycle. This may increase the likelihood that licensed dental hygienists remain current and feel more comfortable advising patients on nutrition.

REFERENCES

- Cordain L, Eaton S, Sebastian A, et al. Origins and Evolution of the Western Diet: Health Implications for the 21st Century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:341–354.

- Varela-López A, Giampieri F, Bullón P, Battino M, Quiles JL. A systematic review on the implication of minerals in the onset, severity, and treatment of periodontal disease. Molecules. 2016;21:1183.

- Ly V, Bottelier M, Hoekstra P, Vasquez A, Buitelaar J, Rommelse N. Elimination diets’ efficacy and mechanisms in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26:1067–1079.

- Gehrig J, Willmann D. Foundations of Periodontics for the Dental Hygienist. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2016; 229-243, 290-299.

- Najeeb S, Zafar M, Khurshid Z, Zohaib S, Almas K. The role of nutrition in periodontal health: an update. nutrients. Nutrients. 2016;8:9.

- Arthritis Foundation. Food Ingredients and Inflammation. Available at: arthritis.org/living-with-arthritis/arthritis-diet/foods-to-avoid-limit/food-ingredients-and-inflammation-2.php. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S, et al. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:911–916.

- Woelber JP, Bremer K, Vach K, et al. An oral health optimized diet can reduce gingival and periodontal inflammation in humans – a randomized controlled pilot study. BMC Oral Health. 2016;17:1.

- Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu F, Willett W. Fruit and vegetable intakes, C-reactive protein, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1489–1497.

- Varela-López A, Giampieri F, Bullón P, Battino M, Quiles J. Role of lipids in the onset, progression and treatment of periodontal disease. a systematic review of studies in humans. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1202.

- Han S, Leka L, Lichtenstein A, Ausman L, Schaefer E, Meydani S. Effect of hydrogenated and saturated, relative to polyunsaturated, fat on immune and inflammatory responses of adults with moderate hypercholesterolemia. J Lipid Res.2002;43:445–452.

- Micallef M, Munro I, Garg M. An inverse relationship between plasma n-3 fatty acids and C-reactive protein in healthy individuals. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:1154–1156.

- Harvard Health Publications. Foods that Fight Inflammation. Available at: health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/foods-that-fight-inflammation. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- Pulido-Moran M, Moreno-Fernandez J, Ramirez-Tortosa C, Ramirez-Tortosa M. Curcumin and Health. Molecules.2016;21:264.

- Nolan JE. Cultural Diversity: Eating in America-Middle Eastern. Available at: ohioline.osu.edu/ factsheet/hyg-5256. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Canadian Arab Community. Arabic Cuisine. Available at: canadianarabcommunity.com/ arabiccuisine.php. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Manzel A, Muller D, Hafler D, Erdman S, Linker R, Kleinewietfeld M. Role of “Western Diet” in Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14:404.

- United States Department of Agriculture. What We Eat in America Food Categories 2013-2014. Available at: ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/ 1314/Food_categories_2013-2014.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu F, Willett W. Dietary patterns and markers of systemic inflammation among Iranian women. J Nutr. 2007;137:992–998.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed December 27,2017.

- US Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Agriculture. 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Available at: health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Sculley DV. Periodontal disease: modulation of the inflammatory cascade by dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Periodontal Res. 2013;49:277–281.

- Dodington DW, Fritz PC, Sullivan PJ, Ward WE. Higher intakes of fruits and vegetables, β-carotene, vitamin c, α-tocopherol, epa, and dha are positively associated with periodontal healing after nonsurgical periodontal therapy in nonsmokers but not in smokers. J Nutr. 2015;145:2512–2519.

- Hayes MJ, Wallace JP, Coxon A. Attitudes and barriers to providing dietary advice: perceptions of dental hygienists and oral health therapists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2016;14:255–260.

- Johnson DL, Gurenlian JR, Freudenthal JJ. A study of nutrition in entry-level dental hygiene education programs. J Dent Educ. 2016;80:73–82.

- Healthy People 2020. Nutrition and Weight Status. Available at: healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/nutrition-and-weight-status. Accessed December 27, 2017.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2018;16(01):34-36,39.

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY FOODS

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY FOODS DIETARY COUNSELING

DIETARY COUNSELING

Great information for a hygienist to have to inform patients and motivate progressive changes.