Caries Prevention for Kids

The systemic use of fluoride provides many benefits in reducing tooth decay.

Reducing the risk of caries and enamel demineralization is key to improving the oral health of our youngest patients.1 Fluoride therapy, in addition to healthy nutrition, good oral hygiene, and professional dental care, is an important tool in the caries prevention armamentarium.2 While fluoride can be delivered topically through varnish, dentifrices, mouthrinses, gels, and foams, it can also be used systemically, which is the focus of this article.

FLUORIDE FACTS

Fluoride is a naturally occurring trace mineral. Like calcium, iron, and other minerals, it is often found in natural sources of ground water. Fluoride’s caries-preventive action was first discovered in the 1920s and 1930s in one of nature’s own experiments. The incidence of dental caries in areas with naturally occurring fluoride in the water supply was 50% lower than in areas with reduced fluoride levels.1,2 This discovery was followed by studies in which dental epidemiologists and dental practitioners performed water fluoridation trials in the 1940s and 1950s, establishing the foundation for the systemic use of fluoride today.3 Further research showed that fluoride prevents caries by promoting enamel remineralization and altering bacterial metabolism.4,5

MECHANISM OF ACTION

Dental caries begins with a disturbance in the balance between enamel demineralization and remineralization. On the enamel surface, fluoride ions replace hydroxide groups and combine with calcium and phosphate within enamel to form fluorohydroxyapatite. This form of crystalline mineral is more resistant to the acid produced by cariogenic bacteria, thus reducing the risk of enamel demineralization and increasing the rate of remineralization.6 Fluoride that is ingested, either from food or water, enters the bloodstream and becomes incorporated into enamel during dental development. In addition, some systemic fluoride delivery methods, such as water, chewable pills, and drops, can produce low concentrations of fluoride ions in saliva, thereby creating a topical effect on the biofilm. When used topically, even a small amount of fluoride is effective in shifting the demineralization/remineralization balance toward remineralization.

Fluoride also affects the physiology of dental bacteria.5,7 Its antimicrobial effects may support its anticaries efforts. Fluoride anion efficiently enters bacterial cells at acidic pH levels, and dissociates when exposed to the more neutral intracellular environment.5 This disassociated form of fluoride can alter the metabolism and growth of many bacterial organisms including Streptococcus mutans.5 The balance between pathological and preventive factors can be weighed toward prevention through the efforts of the dental team, particularly the dental hygienist.8

SYSTEMIC DELIVERY

Well-controlled clinical trials have validated the safety and anticaries effects of fluoride supplementation, and community water fluoridation has been named by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as one of the top 10 public health achievements of the 20th century.9 The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Dental Association (ADA) all recommend fluoride intake either via drinking water or dietary supplements for children age 6 months to 16 years who are at moderate to high risk of dental caries.10,11

Fluoridated water at optimal levels supports the oral health of all children but provides the greatest benefits to those with limited access to professional dental care. Water fluoridation reduces the need for restorative dentistry, tooth loss, time away from work or school, and anesthesia-related risks associated with dental treatment.10 Studies have also shown that the long-term use of fluoride in children can reduce the cost of oral health care by as much as 50%.12

Fluoridated water is now frequently included in processed foods and beverages, which has created the so-called “halo” effect. In addition to drinking water, fluoridated water can be found in infant formulas and foods, milk, fruit juices, carbonated soft drinks, raisins, tea, and cereal. Because of the halo effect and changing patterns of water consumption, particularly in warmer regions of the country, the US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Environmental Protection Agency have revised the recommended optimal levels of water fluoridation from a range of 0.7 mg/l to 1.2 mg/l to simply 0.7 mg/l.13 This new recommendation is subject to publication of final approval.

In order to recommend the appropriate type and dosage of fluoride therapy, the child’s daily fluoride exposure must be determined. The CDC maintains a website that allows consumers and dental providers to check the fluoridation status of their community water supply (apps. nccd.cdc.gov/ MWF/ Index.asp).14

All sources of dietary fluoride should be considered when determining total exposure.15 This can often be difficult because many manufacturers of foods, beverages, and infant formula do not include fluoride concentration with the nutritional information on food labels. Because determining a child’s total fluoride exposure is challenging, the decision to prescribe fluoride supplementation should be made with care and as much information as possible.

Determining the appropriate fluoride exposure in infants is particularly challenging. An ADA expert panel report encourages clinicians to follow the American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines for infant nutrition. These guidelines recommend exclusive breastfeeding for children from birth to 6 months and continued breastfeeding until at least 1 year.16 For children using infant formula, powdered or liquid concentrate infant formulas reconstituted with optimally fluoridated drinking water is recommended while noting the potential risk of enamel fluorosis.16 If there is a risk of enamel fluorosis, ready-to-feed formula should be used, which usually contains fluoride at lower than optimal levels.

When the risk of fluorosis is a concern and parents prefer powdered or liquid concentrate formula, they should be reconstituted with nonfluoridated water or water that has a low concentration of fluoride.16 Water labeled “purified,” “demineralized,” “deionized,” and “distilled” is typically fluoride free or contains low concentrations.

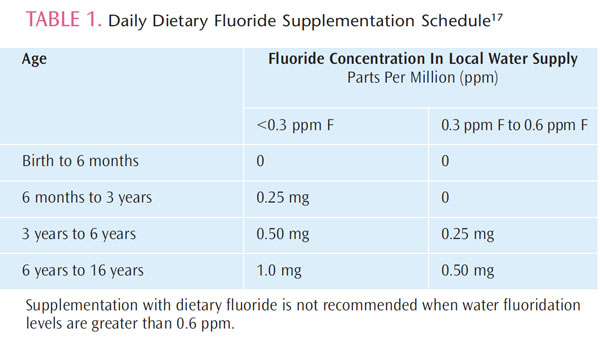

Special care should be taken when measuring a child’s total fluoride intake if water filters are used in the home. Countertop filters and pitcher-type filters usually don’t remove fluoride, but other filters, such as the reverse osmosis kind, can remove fluoride. If fluoride daily intake is suboptimal (less than 0.6 ppm), and the child’s caries risk is moderate or high, then supplementation should be considered. The AAPD provides a supplementation schedule to determine the daily fluoride supplement dosage (Table 1).17

In general, fluoride tablets or drops are not prescribed when public water supplies are fluoridated. Performing a comprehensive prenatal and infant medical history is critical to ascertain all sources of fluoride exposure. For example, many infants are prescribed vitamin drops that may contain fluoride. The use of prenatal fluoride supplements is not recommended.17

TOO MUCH OF A GOOD THING

While fluoride is safe and effective, too much exposure has negative consequences. Enamel fluorosis is the most common side effect. This mainly cosmetic issue usually marks the maxillary central and lateral incisors with white specks or streaks. Fluorosis is caused by ingesting too much fluoride while the enamel is forming, typically between the ages of 1 and 4. The most common cause of fluorosis is children consuming too much dentifrice while toothbrushing or “eating” toothpaste straight from the tube.16 Caregivers should supervise the dispensing of toothpaste and toothbrushing until a child is 7—especially during the high risk period between ages 1 and 4. Taking fluoride supplements when a child is already receiving enough fluoride exposure from other sources may also lead to fluorosis. On the whole, however, the anticaries benefits provided by fluoride outweigh the risk of mild fluorosis, but parents should be educated about the consequences of excessive fluoride exposure.

REFERENCES

- Peterson J. Solving the mystery of the Colorado brown stain. J Hist Dent.1997;45:57–61.

- Herschfeld JJ, Frederick S. McKay and the “Colorado brown stain.” Bull Hist Dent. 1978;26:118–126.

- Adair SM. Evidence-based use of fluoride in contemporary pediatric dental practice. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:133–142.

- Featherstone JD. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:877–899.

- Breaker RR. New insight on the response of bacteria to fluoride. Caries Res. 2012;46:78–81.

- Pizzo G, Piscopo MR, Pizzo I, Giuliana G. Community water fluoridation and caries prevention: a critical review. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11:189–193.

- Koo H. Strategies to enhance the biological effects of fluoride on dental biofilms. Adv Dent Res. 2008;20:17–21.

- Featherstone JD. Caries prevention and reversal based on the caries balance. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:128–132.

- Public Health Service Department of Health and Human Services. Review of Fluoride: Benefits and Risks. February 1991. Available at:www.health.gov/environment/ReviewofFluoride. Accessed January 15, 2013.

- Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. Ten great public heath achievements—United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.1999;48:241–243.

- American Dental Association. ADA Fluoridation Policy and Statements—Fluoridation. Available at: www.ada.org/4045.aspx. Accessed January 15, 2013.

- Griffin SO, Jones K, Tomar SL. An economic evaluation of community water fluoridation. J Pub Health Dent. 2001;61:78–86.

- S Department of Health and Human Services. HHS and EPA announce new scientific assessments and actions on fluoride. Available at:www.hhs.gov/news/press/2011pres/01/20110107a.html. Accessed January15, 2013.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.My Water’s Fluoride. Available at: www.apps.nccd.cdc.gov/MWF/Index.asp.Accessed January 15, 2013.

- Levy SM, Kohout FJ, Kiritsy MC, Heilman JR, Wefel JS. Infants’ fluoride ingestion from water, supplements and dentifrice. J Am Dent Assoc.1995;126:1625–1632.

- Berg J, Gerweck C, Hujoel PP, et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding fluoride intake from reconstituted infant formula and enamel fluorosis: a report of the American Dental AssociationCouncil on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:79–87.

- American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Liaison with Other Groups Committee; American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on ClinicalAffairs. Guideline on fluoride therapy. Pediatr Dent. 2011–2012;33:153–156.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2013; 11(2): 34, 36–37.