LADIMIRFLOYD/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

LADIMIRFLOYD/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Xerostomia Diagnosis and Management

Early detection and treatment are important to effectively manage this common oral condition.

Xerostomia, or perceived dry mouth, has a broad range of prevalence, ranging from 5.5% to 65%, while also considered under-reported by patients and under-recognized by practitioners.1,2 As such, it is important for oral health professionals to remain well-versed in xerostomia, its etiologies, and its diagnosis. Oral health professionals should be confident in assessing patients for xerostomia and providing strategies to improve quality of life for those with this common condition.

True dry mouth is related to salivary gland hypofunction (SGH) and may be caused by medication usage, alcohol or tobacco use, dehydration, medical treatment, or systemic/autoimmune disorders. Categorized as temporary, intermediate or severe, xerostomia is characterized by the subjective reporting of symptoms caused by low salivary flow. It is a common symptom of SGH but can occur without measurable reduction in salivary flow.1-4

Dental hygienists often recognize the clinical aspects of xerostomia, yet patients may deny experiencing symptoms. The severity of symptoms varies from mild to moderate to severe dryness. Severe dryness affects individuals’ ability to speak, chew, swallow, and wear dentures comfortably.3,4 Xerostomia also increases the risk for caries, periodontal and gingival diseases, and oral malodor.1-4

ETIOLOGIES

Symptoms of xerostomia are caused by changes in composition and amount of saliva produced, and may include full dysfunction of salivary glands.1–3 The causes of xerostomia are multifactorial and may not be identifiable in all cases. Many cases of mild to moderate (temporary or intermediate) dry mouth can be attributed to anxiety, smoking, and alcohol consumption. Causes of more severe symptoms include polypharmacy (ingestion of multiple medications at once), chemotherapy or radiotherapy that damages salivary glands, and systemic or autoimmune diseases that result in salivary gland dysfunction.1–3

The simplest cause of xerostomia is dehydration, yet the most common cause is polypharmacy.3,4 More than 500 of the most frequently prescribed medications list xerostomia as a side effect. The drugs most closely associated with xerostomia are:1–4

- Anticholinergics (dementia, asthma)

- Antihistamines and decongestants (allergies)

- Antihypertensives (blood pressure)

- Opioids (pain management)

- Psychotropic (antidepressants and antipsychotics)

- Ulfonylureas (diabetes)

- Skeletal muscle relaxants

Xerostomia is more a function of increased medication use than a result of age.1–3 In fact, the prevalence of dry mouth among adolescents is growing due to their increased use of inhalers, medications used to treat diabetes and attention deficit disorders, mouth breathing, and dehydration.5,6

ROLE OF SALIVA

Typical salivary production ranges from 0.5 liters to 1.5 liters daily. It primarily consists of water; electrolytes, including sodium, potassium, calcium, bicarbonate, and phosphate; and immune and nonimmune salivary proteins, such as immunoglobulins, proteins, enzymes, and mucins.4–6 Proteins and mucins from minor salivary glands act as lubricants, coating oral tissues and protecting the mucosa from chemical, microbial, and physical injury. Saliva’s role also includes keeping tissues moist, aiding in the mastication and digestion processes, and cleansing and buffering the pH of the oral cavity, helping to prevent demineralization. Reduction in quality and quantity of saliva can increase biofilm accumulation and biofilm-related gingival diseases, along with increased caries risk and malodor.4,7,8

Patients become symptomatic when salivary flow drops by 40% to 50%.5 Dry mouth symptoms may worsen at night due to reduced salivary output, as the human body reaches its lowest circadian levels during sleep, which can also be exacerbated by mouth breathing.4,7

ASSESSMENT

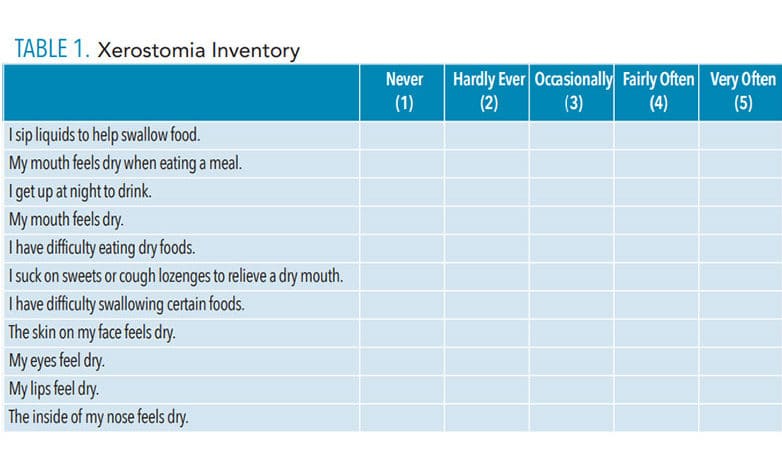

Dental hygienists are prepared to clinically detect xerostomia, often identifying its presence long before a patient reports it. Assessment tools are available to aid oral health professionals in the detection of dry mouth. These include the patient’s health history, Xerostomia Inventory (Table 1), and Clinical Oral Dryness Scale (CODS), which can be accessed at: nature.com/articles/sj.bdj.2011.884.9–11 The health history provides important information about the patient’s systemic health, current medications, and social habits (alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and hydration). The Xerostomia Inventory questionnaire consists of 11 questions.9,10 Each question is answered based on the frequency of symptoms, scoring from 1 to 5:

- Never

- Hardly ever

- Occasionally

- Fairly often

- Very often

The patient answers the following statements referring to the preceding 4 weeks: I sip liquids to aid in swallowing food; my mouth feels dry when eating a meal; I get up at night to drink; my mouth feels dry; I have difficulty in eating dry foods; I suck sweets or cough lozenges to relieve dry mouth; I have difficulties swallowing certain foods; the skin of my face feels dry; my eyes feel dry; my lips feel dry; the inside of my nose feels dry. The score provides information about who is most likely to need management recommendations or a referral. The greater the score, the greater the need for intervention.9,10 The input also helps clinicians to start a conversation about the possibility of xerostomia.

The symptom information gleaned from the Xerostomia Inventory can be discussed in tandem with findings from a quick clinical evaluation using the CODS.11 The CODS is a 10-point scale, with a score of 1 or 0 assigned to each item indicating the presence or lack of a clinical sign. A higher score indicates increased severity and supports the need for management or referral to a salivary specialist. This tool uses images and descriptions of oral dryness to assess the patient. The severity level of clinical oral dryness is determined with scores of:

The symptom information gleaned from the Xerostomia Inventory can be discussed in tandem with findings from a quick clinical evaluation using the CODS.11 The CODS is a 10-point scale, with a score of 1 or 0 assigned to each item indicating the presence or lack of a clinical sign. A higher score indicates increased severity and supports the need for management or referral to a salivary specialist. This tool uses images and descriptions of oral dryness to assess the patient. The severity level of clinical oral dryness is determined with scores of:

1–3: Mild

4–6: Moderate

7–10 Severe

Each item (1 through 10) is worth either 0 or 1 point. Clinical signs of mild xerostomia are described as “mirror sticks to buccal mucosa, mirror sticks to tongue, and/or saliva is frothy.” The second section describes more severe signs as “no saliva pooling on floor of mouth, tongue shows sign of generalized shortened papilla (mild depapillation, Figure 1) and/or altered gingival architecture (ie, smooth). The third section describes the most severe signs as “glossy appearance of oral mucosa, especially palate; tongue lobulated, fissure; cervical caries (more than two teeth); and/or debris on palate or sticking to teeth.”11

THE IMPORTANCE OF STRATEGY

Multiple strategies are available to assist patients in managing xerostomia. Their purpose is to reduce symptoms and/or increase salivary flow, thus reducing the incidence of oral disease. The patient can consider increasing fluid intake and decreasing use of caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco. Patients may also be advised to increase humidity at night, avoid using toothpastes that contain sodium lauryl sulphate, which may be irritating, and stop consuming crunchy/hard foods. They should use soft toothbrushes, mouthrinses with fluoride or prescription-strength fluoride, and sugar-free chewing gums/candy to stimulate salivary flow.7 While chewing stimulates salivary flow, only gums that list xylitol as their first ingredient should be used.12,13 There are several over-the-counter mucosal lubricants , saliva substitutes, and saliva stimulants with xylitol, including in oral-adhering discs, that help maintain the feeling of moisture in the mouth.

Dental hygienists must consider how their treatment may impact the patient with xerostomia in the course of a typical appointment. In-office management must be tailored to include the use of fine prophy pastes, which are less abrasive to tissue, limiting the use of air polishers or prophy jets, regular plaque removal and application of fluoride, vigilance in caries assessments (coronal and cervical), and continuous monitoring for oral lesions and recession. Evaluating dental appliances and prosthetics (nightguards, full and partial removable dentures) for fit and noting any need for adjustments. Ongoing nutritional counseling to reduce sugar and carbohydrate consumption is also important. Regular review of the patient’s medications so those that cause dry mouth may be replaced with an alternative or reduced after discussion with his or her primary care physician.

When a patient presents with severe xerostomia/SGH, it may be necessary to meet with the supervising dentist to discuss a more significant intervention. Prescription medications (systemic sialogogues) are prescribed to improve salivary flow resulting from salivary gland dysfunction. This may be warranted for patients who have undergone head and neck radiotherapy or have Sjögren syndrome.1–4,14

Systemic sialogogues, such as pilocarpine and cevimeline, are highly effective at returning salivary flow, yet they have significant extended effects such as excessive sweating, nausea, rhinitis, chills, flushing, and excessive urination. Both medications are cholinergic agonists or anti-cholinergic drugs, which act to block the “flight” part of the autonomic fight or flight reaction, thus turning secretions (including saliva) back on. While they are effective on dysfunctional salivary glands they also act elsewhere.12,13

CONCLUSION

Maintaining open and clear communication with patients is essential to their well-being. Patients with xerostomia require dental hygienists to detect this common disorder early and provide coordinated management for positive health outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Navazesh M, Kumar SK. Xerostomia: prevalence, diagnosis, and management. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2009;6;326–332.

- Plemons JM, Al-Hashimi I, Marek CL. Managing xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction: a report of the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:867–873.

- American Dental Association. Xerostomia. Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/xerostomia. Accessed March 11, 2020.

- Villa A, Connell CL, Abati S. Diagnosis and management of xerostomia and hyposalivation. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:45–51.

- Pappa E, Vastardis H, Rahiotis C. Chair-side saliva diagnostic tests: An evaluation tool for xerostomia and caries risk assessment in children with type 1 diabetes. J Dent. 2020;93:103224.

- Dubey S, Saha S, Tripathi AM, Bhattacharya P, Dhinsa K, Arora D. A comparative evaluation of dental caries status and salivary properties of children aged 5–14 years undergoing treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, type I diabetes mellitus, and asthma in vivo. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2018;36:283–289.

- Hemalatha VT, Julius A, Kishore Kumar SP, Periyasamy TT, Mani Sundar N. Xerostomia: a current update for practitioners. Journal: Drug Invention Today. 2019;12(3):388–392.

- Brand RW, Isselhard D, Erdman K. Anatomy of Orofacial Structure: A Comprehensive Approach. 8th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2018:352–353.

- Thomson WM, Chalmers JM, Spencer AJ, Williams SM. The Xerostomia Inventory: a multi-item approach to measuring dry mouth. Community Dent Health. 1999;1:12–17.

- Thomson WM, van der Putten GJ, de Baat C, et al. Shortening the Xerostomia Inventory. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:322–327.

- Osailan SM, Pramanik R, Shirlaw P, Proctor GB, Challacombe SJ. Clinical assessment of oral dryness: development of a scoring system related to salivary flow and mucosal wetness. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;5:597–603.

- Chandrashekar JC, Kumar VD, Joseph J. Xylitol in preventing dental caries: A systematic review and meta analyses. J Nat Sc Biol Med. 2017;8:16–21.

- Mäkinen KK, Isotupa KP, Kivilompolo T, Mäkinen PL, Toivanen J, Söderling E. Comparison of erythritol and xylitol saliva stimulants in the control of dental plaque and mutans streptococci. Caries Res. 2001;35:129–135.

- Garlapati K, Kammari A, Badam RK, Surekha BE, Boringi M, Soni P. Meta-analysis on pharmacological therapies in the management of xerostomia in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2019;41:2:312–318.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2020;18(4):22-24,26.