REDHUMV/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

REDHUMV/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

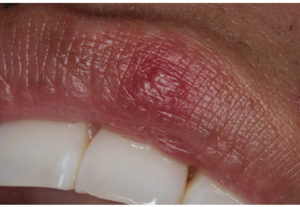

Treating Herpetic Lesions With Laser Therapy

Healing time and pain can be reduced.

This course was published in the April 2020 issue and expires April 2023. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the role of laser therapy in the treatment of herpetic lesions and its effectiveness.

- Identify important safety protocols that must be used during laser therapy.

- Explain the regulations surrounding the ability of dental hygienists to use dental therapy in the treatment of herpetic lesions.

Globally, an estimated 3.7 billion people younger than 50 (67%) have herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 infection, which primarily affects the lips, producing what are commonly called cold sores or fever blisters.1 Oral herpes infections are often asymptomatic, but can cause mild to severe symptoms for many, with painful blisters or ulcers at the site of infection.2 Oral ulcers have been associated with infections, autoimmune diseases, and inflammation. Antiviral medications, such as acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir, available as tablets, capsules, and topical ointments, are the most commonly prescribed and effective medications.3 These medications can help reduce the severity and frequency of symptoms, but cannot cure the infection.

An alternative treatment for herpes labialis infection is the diode laser. This treatment option alters cell and tissue function, and decreases healing time.3 Based on dental hygiene practice acts and appropriate education and certification, dental hygienists can be assets in the use of diode lasers for the treatment of herpetic lesions.

The laser energy kills the surface virus, thus inactivating the lesion. In this process, nerve endings are cauterized, allowing the patient’s symptoms to resolve. The reduction in healing time is due to the process of photo biomodulation (PBM), a form of infrared light therapy at a specific wavelength that stimulates cells to produce natural healing and reduce pain.4 Wound healing is increased by the formation of fibroblasts, motility of human keratinocytes, promotion of early epithelization, and enhancement of neovascularization.5

TREATMENT PROCESS

Laser therapy should be conducted at the first sign of an HSV-1 outbreak. With laser therapy, the healing time for a herpes lesion may be reduced by 10 days to 14 days and the resultant pain/discomfort should decrease.6

When treating herpetic lesions, the tip of the laser must be a noninitiated tip. This provides the laser’s light energy, compared to initiated tips, which provide heat energy and are often referred to as “hot tips.” Each tip must be individually autoclaved before use and disposed of afterward; they are single use. A noninitiated tip provides a more dispersed laser beam, enabling greater surface area coverage of the herpetic lesion. In contrast, an initiated tip is used for periodontal therapy, in which a hot tip is needed to burn off the diseased tissue and microbial products in the pocket.

The noninitiated tip is used in a back-and-forth or circular motion around the lesion. A circular motion is most commonly used for smaller lesions, starting at the outer edges of the lesion, slowly moving closer to the center of the lesion, while holding the tip about 5 mm from the lip.7 If the lesion is large, clinicians may find the back-and-forth method to be more thorough. No anesthesia is needed for the use of laser therapy in the treatment of herpes labialis.8

EFFECTIVENESS OF LASER THERAPY

Evidence demonstrates the efficacy of laser use in the treatment of herpetic lesions. In a double-blind study, Brignardello-Peterson6 used a low level laser on 60 patients; the control group received no laser therapy. Results showed a reduction of healing time for participants receiving laser treatment for a herpes labialis lesion. Participants reported less pain and a reduction in lesion size, compared to the group that did not receive laser therapy.

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 50 participants with herpes labialis lesions, De Paula Eduardo et al9 found a significant reduction in healing time and a decrease in the recurrence of herpes lesions.

Namar et al8 reported a reduction in microorganisms post-laser therapy, resulting in faster healing. It remains unclear whether healing time improved due to exposure of the actual phototoxicity or the indirect thermal changes. The researchers suggest that healing time will vary depending on the use of longer or shorter settings on the laser wand.

CASE REPORTS

The following two case reports involve a one-time application of laser therapy for the treatment of herpetic lesions. The initiation times of the herpetic lesions were different in each case, but both patients reported the following post-laser therapy: less discomfort, lesions did not grow in size, and lesions crusted over within 1 day of treatment. The most significant change reported was that lesions showed signs of healing and shrinkage much quicker than lesions they had experienced in the past that did not receive laser therapy.

Both cases received the following treatment:

- Laser therapy with noninitiated tip

- Power setting at 1.0 watts

- Stroke:

* Began at 5 mm away from lesion and slowly moved to 2 mm from the lesion

* Circular stroke was used on lesions

* The stroke extended over the border of the lesion by 2 mm

Case One (Figure 1 and Figure 2) and Case Two (Figure 3 and Figure 4) are both women who received treatment with a diode laser immediately upon the presentation of a lesion with vesicles.

The Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature (CDT) provides an efficient means of accurately documenting and processing dental claims. The code submitted for this procedure is: D7465—Destruction of Lesion. According to the National Dental Advisory Service’s Fee Report Schedule, cost can vary dramatically from $356 to $706, and is also scheduled differently from third party payers with varying submittal requirements (photos with scale, etc).

SAFE LASER USE

As with any device that emits radiation, clinicians must follow all safety rules applicable to laser use. The Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses (AORN) has established recommended safety practices when using a laser for patient care.10 Every dental practice that uses a laser for direct patient care should have an employee identified as its laser safety officer. The AORN recommends that all equipment be located on one cart, including the laser itself, eye protection (patient and operator), evacuation system, signs, and masks.10 An organized laser therapy cart promotes efficient operation and can help to prevent any untoward effects on patients or clinicians.

The human eye is extremely sensitive to the concentrated laser beam, which can damage the retina either temporarily or permanently.10 Protective eyewear is essential for both operators and patients. Clinicians must wear safety lenses that protect against wavelengths up to 940 nm.11 The safety glasses must be of the proper thickness, otherwise the provider’s retina may be damaged. Retinal damage is less likely among patients, so typical safety glasses are deemed acceptable protective eyewear.11

Compared with providers, patients are at greatest risk for skin damage. As the laser produces thermal energy, patients are susceptible to soft tissue burns.12 The operator controls and minimizes any potential burn by consistent monitoring of laser settings and appropriate direction of the laser beam. Dark skinned individuals may not be ideal candidates for laser treatments due to their higher melanin pigmentation. The greater melanin level will absorb more of the laser beam, making these individuals more prone to burning and skin damage, regardless of the setting.13 Mustached or bearded men, or women with any stray hairs in the mouth area could result in burning because the laser beam is drawn to the facial hairs, burning them and thus the skin.14

Using a laser to treat soft tissue lesions releases a plume into the air, which may consist of carcinogens, mutagens, irritants, and fine dusts. Plumes may also contain bioaerosols, viruses, blood fragments, and bacteria depending on the type of procedure.9,10 They also contain carbon monoxide, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, and various toxic gases and vapors, and chemicals such as formaldehyde, hydrogen cyanide, acrolein, and benzene.15

Currently, there are no Occupational Safety and Health Administration standards for laser plume hazards; however, these are needed.16 A high-volume evacuation system must always be used when the laser is firing. This will keep the site cool and remove the plume. Nose filters can be added to the personal protective equipment to reduce any viral plume from being inhaled. Nose filters are lightweight, discreet, latex free, and available in multiple sizes. Face masks are required for all patient care procedures and vary in micron thickness.17 The mask used during laser procedures must be 0.1 microns. This will filter 99.9% of all viruses as well as controlling any plume crossing into the mask.18

Reflective surfaces must be minimized in the patient operatory during laser therapy. When reflective surfaces are not covered or removed, the laser can be redirected by bouncing off the metal or mirrored surfaces, possibly injuring the eye. Examples of reflective surfaces are mirrors, earrings, and any metal with a reflective surface.12

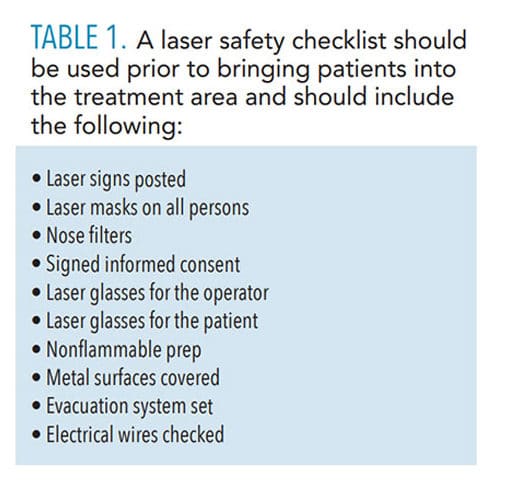

Operatories used in laser therapy must be properly marked with warning signs so that others in the office (staff and patients) do not enter the room without the proper safety equipment. The safety zone for laser use is 8 feet.12 A laser safety checklist should be used prior to bringing the patient into the treatment area (Table 1).

![]() SCOPE OF PRACTICE

SCOPE OF PRACTICE

Dental hygienists interested in using laser therapy must ensure it is within their state practice acts. The Academy of Laser Dentistry has a map demonstrating which states allow the use of laser therapy by dental hygienists. Sixteen states have a written policy that explicitly allows laser use by licensed dental hygienist. Thirty states have a range of regulations, from no mention of laser use, to stipulating the use of lasers by dentists only, to allowing dental hygienists to use laser therapy only for gingival curettage. The remaining four states are either developing a policy or simply do not allow dental hygienists to use laser therapy in any circumstance.19

Laser therapy is not a required part of dental hygiene education so the level of instruction provided on its use varies widely. Dental hygienists who want to learn how to use laser therapy may take a course approved by the state in which they plan to practice.20 Dental hygienists should check with their State Board of Dental Examiners to find a certified class.

CONCLUSION

The use of the diode laser on herpes labialis lesions can be of immense value to both patients and clinicians, reducing bacterial activity and pain.7,9,15 Laser therapy for the treatment of HSV-1 is a service that all dental hygienists should be able to provide (depending on state law).

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Herpes simplex virus. Available at: who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Basirat M. The effects of low power lasers in healing of oral ulcers. Journal of Lasers in Medical Sciences. 2012;3(2):79.

- Honarmand M, Farhadmollashahi L, Vosoughirahbar E. Comparing the effect of diode laser against acyclovir cream for the treatment of herpes labialis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry. 2017;9(6):e729–e732.

- de Paula Eduardo C, Bezinelli LM, de Paula Eduardo F, et al. Prevention of recurrent herpes labialis outbreaks through low-intensity laser therapy: a clinical protocol with 3-year follow-up. Lasers in Medical Science. 2012;27(5):1077–1083.

- Chawla, K, Lamba,AK, Tandon, S, Faraz, F, Gaba, V. Effect of low-level laser therapy on wound healing after depigmentation procedure: A clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2016;20:184.

- Brignardello-Petersen R. Treatment of lesions associated with herpes labialis with low level laser therapy may result in a decrease of pain and recovery time compared with acyclovir. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148:e153.

- Tumlinson J. Getting started with lasers in hygiene. Available at: cdeworld.com/courses/21371-getting-started-with-lasers-in-hygiene. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Namvar MA, Vahedi M, Abdolsamadi H, Mirzaei A, Mohammadi Y, Azizi Jalilian F. Effect of photodynamic therapy by 810 and 940 nm diode laser on herpes simplex virus 1: an in vitro study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2019;25:87–91.

- de Paula Eduardo C, Mello Bezinelli L, de Paula Eduardo F, et al. Prevention of recurrent herpes labialis outbreaks through low-intensity laser therapy: A clinical protocol with 3-year followup. Lasers in Medical Science. 2012;27(5):1077–1083.

- Castelluccio, D. Implementing AORN recommended practices for laser safety. Available at: aornjournal-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/doi/pdfdirect/10.1016/j.aorn.2012.03.001. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Schirmacher A. Eye protection for short and ultra-short pulsed laser system. Medical Laser Application. 2010,25:93–98.

- Singh S, Gambhir RS, Kaur A, et al. Dental lasers: a review of safety essentials. Journal Lasers Medical Science. 2012;3(3):91–96.

- Gorai MA, Kurdysh LF, Popova OI, Kutelmakh OI. Efficient improvements of herpex Simplex labialis treatment using diode laser and “tebodont” gel. Ukrainian Dental Almanac. 2018;1:21.

- Laser and Electrolysis Hair Removal by Aleya. Causes of getting burned during a laser session and how to prevent it. Available at: laserbyaleya.com/blog/causes-of-getting-burned-during-a-laser-session-and-how-to-prevent-it. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety. Laser Plumes—Health Care Facilities. Available at: ccohs.ca/oshanswers/phys_agents/laser_plume.html. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Laser/Electrosurgery Plume. Available at: osha.gov/SLTC/laserelectrosurgeryplume/index.html. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Greco P, Lai C. A new method of assessing aerosolized bacteria generated during orthodontic debonding procedures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:79–87.

- Jankovic J, Ogle B, Zontek T. Suitability of polycarbonate safety glasses for UV laser eye protection. Journal of Chemical Health and Safety. 2016;23(2):29–33.

- Academy of Laser Dentistry. State by State Quick Reference Chart on Laser Use by Dental Hygienists. Available at: laserdentistry.org/uploads/files/Reg%20Affairs/Regulatory%20Chart%20ALL%204_2018%20-%20ALL%20STATES.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- International Center for Laser Education. Laser Certification. Available at: amdlasers.com/pages/free-6-ce-training-with-test. Accessed March 27, 2020.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2020;18(4):42-45.

SCOPE OF PRACTICE

SCOPE OF PRACTICE