The Use of Miswak to Improve Oral Health Outcomes

Commonly used in many cultures, miswak is a potential alternative oral hygiene method.

This course was published in the January 2021 issue and expires January 2024. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the properties of miswak that benefit oral health.

- Compare and contrast miswak with toothbrushing and rinsing with chlorhexidine gluconate.

- Recommend ways to integrate miswak in professional practice.

Oral health professionals recommend many methods, such as toothbrushing, flossing, and mouthrinses, to maintain oral health. Patients who are unable to implement proper oral hygiene care are at higher risk for infections such as gingivitis, periodontitis, and dental caries.1 Those with advanced stages of oral diseases are often prescribed medications, such as chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinse, to help reduce further infections and overgrowth of bacteria.2 For patients who prefer a holistic approach, the use of miswak is a potential alternative method.

Toothbrushes are common oral hygiene implements in European and North American cultures. However, in Arabian, African, Asian, and South American cultures, chewing sticks are the preferred tool for oral cleaning.3,4 Miswak is such a stick, originating from a plant known as Salvadora persica. The use of miswak as an oral aid can be traced back to the Babylonians around 7,000 BCE and then used again later by the Roman, Greek, Egyptian, and various Muslim empires.3,5,6 In different parts of the world, miswak is also referred to as sewak, sewaki, datun, and mefaka, and has been used to remove oral malodor, improve taste, strengthen gingiva, and relieve toothaches.7–9

Miswak is an effective tool that can be used to maintain oral health without side effects. Studies demonstrate that miswak offers several advantages including concurrent analgesic, antiplaque, antifungal, anticariogenic, and antimicrobial properties.3,5,6 Miswak comes in different forms, including a mouthrinse and a chewing stick.5,8,10 The World Health Organization recommends miswak as an adjunct for patients without access to traditional oral hygiene products.3,10 Furthermore, miswak is inexpensive and may be a great recommendation for individuals looking for a natural approach to oral hygiene care.

DENTAL CARIES AND SALIVARY FLOW

The use of miswak may help to reduce the formation of caries.6,11 Miswak roots contain fluoride and gallotannins-a phenolic compound reported to be bactericidal to cariogenic bacteria. These compounds inhibit the growth of oral pathogens, particularly Streptococcus mutans, because they interfere with the streptococcal attachment to dental biofilm.5,12,13 In 2004, Almas and Al-Zeid14 conducted a clinical study in 40 healthy men to assess the antimicrobial effect of miswak on S. mutans and Lactobacilli, using a commercial caries risk test. The subjects were divided equally into four groups: miswak group, 50% miswak extract group, standardized toothbrush group, and saline group (control). Results showed a greater reduction of S. mutans in the miswak groups than in the toothbrush group. There were no significant differences in Lactobacilli count between all four groups.

Chewing the miswak stick also stimulates salivary flow, which helps reduce caries risk. Saliva plays a vital role in maintaining homeostasis by balancing the pH in the oral cavity.15,16 In 2013, Khalil et al16 studied the relation of electrolytes and pH in miswak and toothbrush users. An electrolyte and ion selective electrode analyzer and pH measurement were used to measure calcium, phosphate, sodium, and potassium content of the acquired samples. The researchers noted a significant difference in miswak users, who displayed a higher amount of salivary sodium, calcium, plaque calcium, and phosphate content when compared to toothbrush users. Saliva promotes remineralization of the enamel. The increase of phosphate and calcium ions stimulated from the miswak buffers the dental biofilm pH, suggesting that the miswak has a potential role in caries prevention.15

PERIODONTAL DISEASES

In addition to caries prevention, miswak is effective in reducing dental biofilm and gingivitis when preceded by professional instructions regarding its correct use.6,17,18 In 2014, Malik et al17 conducted a clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of a miswak stick with a toothbrush in biofilm removal and gingival health. Overall, the miswak stick provided the same or even greater mechanical and chemical cleansing of oral tissues compared with a toothbrush. The results demonstrated a significant decrease in the biofilm score compared to the baseline. In 2012, Patel et al18 compared the effectiveness of combining both a toothbrush and miswak in removing biofilm on 30 subjects. The results showed that the biofilm score and gingival health improved significantly when using a toothbrush and miswak together in comparison to using miswak or toothbrushes alone. In both studies, oral hygiene instructions were provided to subjects. Dental hygienists need to educate patients on the proper use of a toothbrush and miswak stick for effective outcomes.

ORAL CANDIDIASIS

Miswak also has antifungal effects helpful against oral candidiasis, which commonly occurs in immunocompromised individuals.3,5,19 In 2008, Al-Bayati et al19 suggested that the antifungal effect of miswak is due to its chemical contents: chlorine, trimethylamine, alkaloid resin, and sulfur compounds. In 2002, Al-Mohaya et al20 assessed the relationship between miswak and oral candidiasis in renal transplant patients. The participants were classified into two groups: miswak user group (n=25) and nonmiswak user group (n=33). The results showed that eight of 33 (24.2%) nonmiswak users had oral candidiasis, which was significantly higher than one out of 25 (4%) of miswak users. Overall, renal transplant patients who used the miswak had lower prevalence of oral candidiasis than those who did not use the miswak. Moreover, miswak in the extracted phase (dried miswak and methanol mixture) still had the same antifungal effect as the miswak stick.19 In 2014, Naeine et al21 found that miswak’s alcohol extracts have strong to moderate effects against Candida species, including C. albicans. This suggests that miswak may be effective in counteracting oral candidiasis in immunocompromised patients.

DENTAL STAINING

Miswak’s embedded crystals act as an abrasive agent by removing the pigment and biofilm on tooth surfaces. In 2017, Halib et al22 examined the S. persica fibers with a scanning electron microscope and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. They found the miswak’s fibers were composed of a spongy structure embedded with irregular-shaped crystals. The researchers further assessed the use of S. persica crystals to alleviate extrinsic tooth staining, compared to a commercial whitening toothpaste. Both the S. persica paste and toothpaste were applied to a toothbrush with a rounded brush head. Based on the whitening shade guide, the concentrated S. persica paste showed a two-shade to three-shade improvement within minutes of exposure, compared to the toothpaste, which reduced extrinsic staining by only one shade.

TOOTHBRUSHING AND TOOTHBRUSHES

In comparison to a toothbrush, miswak has a fibrous stick tapered on one end and frays into a brush-like form (Figure 1).3 The brush-like edge of the miswak stick starts to shred after being used several times and becomes ineffective.3 The end of the miswak stick can be further cut off and chewed to expose a fresh new end.23 The natural oral aid allows patients to use it several times for a series of weeks or until the stick has reached its limit. Furthermore, the bristle-like fibers allow patients with embrasure spaces to access and clean interproximal areas. In other words, patients with type II and type III embrasure spaces can use a miswak stick instead of an additional interproximal oral aid to maintain oral hygiene.

In 1990, Gazi et al3 showed miswak decreased biofilm when used five times a day as compared to using the toothbrush twice a day. In short, patients who use miswak need to brush more frequently in order to see a noticeable reduction in biofilm and gingivitis.

The miswak stick is more than a toothbrush because its root and stem contain phytochemicals that replenish teeth with natural properties such as chloride, an antiplaque chemical, and vitamin C, a collagen stimulant that accelerates the gingival healing process.23 Benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC) is an important antibacterial and anticariogenic component found in miswak.3,24 In 2011, Sofrata et al25 found the BITC in S. perisca roots to be bactericidal to Gram-negative periodontal pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregaticbacter actinomycetemcomitans.3,25

USE OF MOUTHRINSES

Miswak mouthrinse can be used as an alternative to 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinses in the management of periodontal health. In 2017, Nishad et al26 performed a randomized clinical trial on 60 subjects who were divided equally into three groups: chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinse, Azadirachta indica (similar to miswak) mouthrinse, and distilled water (control). The trial showed that A. indica mouthrinse effectively reduced the quantity of S. mutans colonies similar to chlorhexidine gluconate. Comparably to miswak, the A. indica mouthrinse was also effective in reducing both the plaque index and gingival index.

Additionally, in 2018, Niazi et al27 compared the antiplaque effects of two herbal mouthrinses composed of 10% S. persica (miswak) and 10% A. indica with two synthetic mouthrinses containing either 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate or 0.05% cetylpyridinium. The S. persica group showed a significant reduction in dental biofilm compared to the 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate.

Chlorhexidine gluconate, like the miswak, is safe and effective in breaking down existing dental biofilm; however; chlorhexidine use comes with some side effects. The common long-term side effects of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate include extrinsic brown staining of the teeth and tongue, and accelerated development of supragingival calculus.28

The chemical components of the miswak mouthrinse are similar to the compounds found in the root of the miswak stick. In 2002, Ismail et al29 conducted an in vitro study that examined miswak’s root extract to identify the anionic components using capillary electrophoresis techniques. The results showed the presence of polyatomic ions including chloride, sulfate, nitrate, and thiocyanate in the aqueous extract of the miswak root and stem. Both sulfate and thiocyanate are effective against bacteria that initiate oral biofilm formation and other exogenous accretions from the tooth surface.3,29 The bioactive compounds in miswak extract were found to be beneficial by interfering with the gingipains and leukotoxins respectively produced by P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans in destroying tooth-supporting tissues.3,30

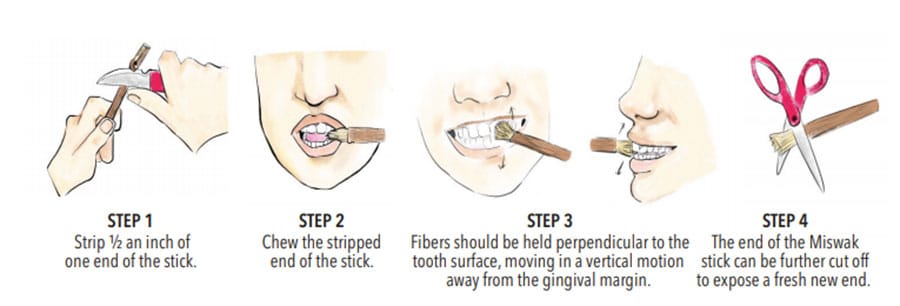

HOW TO USE THE MISWAK STICK

To use a miswak stick, first strip half an inch of one end of the stick, then chew it (Figure 2). Next, patients will hold the other end of the stick using a pen grasp to clean each tooth. The fibers should be held perpendicular to the tooth surface moving in a vertical motion away from the gingival margin on both buccal and lingual margins. The end of the miswak stick can be further cut off and chewed to expose a fresh new end. Similar to a toothbrush, miswak can be gently brushed in areas such as on or under the tongue, gingiva, palate, and buccal mucosa.6 Educating patients on the proper angulation and usage of the stick is essential to preventing problems caused by incorrect use, such as abrasion and gingival recession.9

Patients may purchase miswak from a variety of in-person and online retailers, and comes as a stick, mouthrinse, powder, toothpaste, and brush heads. Patients should seek advice from an oral health professional to help determine which type of miswak is suitable for their needs.

ROLE OF ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

Oral health professionals should remain current in their knowledge of miswak, among other alternative oral hygiene products, and recommend a diverse array of oral hygiene aids to improve patients’ oral health. Moreover, oral health professionals can educate miswak users on proper brushing technique to prevent tooth abrasion, recession, and gingival trauma. For patients with limited access to dental care and/or in financial constraints, miswak agents, such as stick and rinses, can be recommended as an economical alternative. Lastly, oral healthcare professionals can promote miswak benefits to patients who prefer a more holistic and natural approach to oral hygiene care.

CONCLUSION

Miswak is a versatile, cost-effective, user-friendly, natural oral aid that may appeal to those who prefer a more holistic approach to traditional oral hygiene care. Available in a variety of forms, research demonstrates its effectiveness in reducing the risk of oral diseases from caries to periodontitis. Additional research is needed to determine additional benefits of miswak use on oral health.

REFERENCES

- Hitz Lindenmüller I, Lambrecht JT. Oral care. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2011;40:107–115.

- da Costa LFNP, Amaral CDSF, Barbirato DDS, Leão ATT, Fogacci MF. Chlorhexidine mouthwash as an adjunct to mechanical therapy in chronic periodontitis: a meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148:308–318.

- Mohammad H, Saeed A. A review of the therapeutic effects of using Miswak (Salvadora persica) on oral health. J Saudi Med. 2016;36:530–543.

- Dahiya P, Kamal R, Luthra RP, Mishra R, Saini G. Miswak: a periodontist’s perspective. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012;3:184–187.

- Niazi F, Naseem M, Khurshid Z, Zafar MS, Almas K. Role of Salvadora persica chewing stick (miswak): a natural toothbrush for holistic oral health. Eur J Dent. 2016;10:301–308.

- Aumeeruddy MZ, Zengin G, Mahomoodally MF. A review of the traditional and modern uses of Salvadora persica L. (miswak): toothbrush tree of Prophet Muhammad. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018; 213:409–444.

- Halawany H. A review on miswak (Salvadora persica) and its effect on various aspects of oral health. Saudi Dent J. 2012;24:63–69.

- Akhtar J, Siddique KM, Bi S, Mujeeb M. A review on phytochemical and pharmacological investigations of miswak (Salvadora persica Linn). J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3:113–117.

- Wu CD, Darout IA, Skaug N. Chewing sticks: timeless natural toothbrushes for oral cleansing. J Periodontal Res. 2001;36:275–284.

- Basil H. The miswak (Salvadora persica L.) chewing stick: cultural implications in oral health promotion. Saudi J Dent Res. 2014;5:9–13.

- Al-Qudah IH, Radaideh AA, Ahmed N, Mathew A. Comparison of antibacterial efficacy of miswak extract to conventional mouth washes—a microbiological study. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia. 2017;14:99–104.

- Kang MS, Oh JS, Kang IC, Hong SJ, Choi CH. Inhibitory effect of methyl gallate and gallic acid on oral bacteria. J Microbiol. 2008;46:744–750.

- Gan RY, Kong KW, Li HB, et al. Separation, identification, and bioactivities of the main gallotannins of red sword bean (Canavalia gladiata) coats. Front Chem. 2018;6:39.

- Almas K, Al-Zeid Z. The immediate antimicrobial effect of a toothbrush and miswak on cariogenic bacteria: a clinical study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2004;5:105–114.

- Abhary M, Al-Hazmi AA. Antibacterial activity of miswak (Salvadora persica L.) extracts on oral hygiene. J Taibah Univ Sci. 2016;10:513–520.

- Khalil WA, MY Sukkar, BG Gismalla, Oral health and its relation to salivary electrolytes and pH in miswak and brush users. Khar Med J. 2013;6:859–863.

- Malik AS, Shaukat MS, Qureshi AA, Abdur R. Comparative effectiveness of chewing stick and toothbrush: a randomized clinical trial. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:333–337.

- Patel PV, Shruthi S, Kumar S. Clinical effect of miswak as an adjunct to tooth brushing on gingivitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:84–88.

- Al-Bayati FA, Sulaiman KD. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Salvadora persica L. extracts against some isolated oral pathogens in Iraq. Turk J Biol. 2008;1:57–62.

- Al-Mohaya MA, Darwazeh A, Al-Khudair W. Oral fungal colonization and oral candidiasis in renal transplant patients: the relationship to miswak use. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:455–460.

- Naeini A, Naderi NJ, Shokri H. Analysis and in vitro anti-Candida antifungal activity of Cuminum cyminum and Salvadora persica herbs extracts against pathogenic Candida strains. J Mycol Med. 2014;24:13–18.

- Halib N, Nuairy NB, Ramli H, et al. Preliminary assessment of Salvadora persica whitening effects on extracted stained teeth. J App Pharm Sci. 2017;7:121–125.

- Yasmin W, Ramli H, Alias A. Miswak: the underutilized device and future challenges. J Dent Oral Hyg. 2019;11:6–11.

- Farag MA, Fahmy S, Choucry MA, Wahdan MO, Elsebai MF. Metabolites profiling reveals for antimicrobial compositional differences and action mechanism in the toothbrushing stick “miswak” Salvadora persica. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2017;133:32–40.

- Sofrata A, Santangelo EM, Azeem M, Borg-Karlson AK, Gustafsson A, Pütsep K. Benzyl isothiocyanate, a major component from the roots of Salvadora persica is highly active against Gram-negative bacteria. PLos One. 2011;6:e23045.

- Nishad A, Sreesan NS, Joy J, Lakshmanan L, Thomas J, Anjali VA. Impact of mouthwashes on antibacterial activity of subjects with fixed orthodontic appliances: a randomized clinical trial. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2017;18:1112–1116.

- Niazi FH, Kamran MA, Naseem M, AlShahrani I, Fraz TR, Hosein M. Anti-plaque efficacy of herbal mouthwashes compared to synthetic mouthwashes in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment: a randomised controlled trial. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2018;16:409‐416.

- Salehi P, Momeni DS. Comparison of the antibacterial effects of persica mouthwash with chlorhexidine on Streptococcus mutans in orthodontic patients. Daru. 2006;14:178–182.

- Ismail AD, Alfred C, Nils S, Per KE. Identification and quantification of some potentially antimicrobial anionic components in miswak extract. Indian J Pharm. 2000;32:11–14.

- Sofrata AH, Claesson RL, Lingström PK, Gustafsson AK. Strong antibacterial effect of Miswak against oral microorganisms associated with periodontitis and caries. J Periodontal. 2008;79:1474–1479.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2021;19(1):40-43.