Manage the Immune Response

Diabetes and HIV infection generate different immune responses that can significantly impact oral health and periodontal treatment.

This course was published in the September 2012 issue and expires September 2015. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss how the innate and adaptive immune systems work.

- Identify the dental considerations for patients with type 2 diabetes.

- Explain how human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) affects the adaptive immune system.

- Detail the dental considerations for patients with HIV infection.

More than 25 million Americans have diabetes, with 90% presenting with type 2 diabetes.1 Over 1 million adolescents and adults in the United States are infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), with approximately 50,000 new cases emerging each year.2 Of those infected, one in five are unaware of their condition.2 Diabetes and HIV infection both generate different immune responses, which can greatly affect oral health and the provision of professional dental care. Periodontal diseases are common among both patient populations, but the type of disease, contributing factors, and susceptibility are very different. Both patient cohorts suffer from a distressed immune system, which plays a part in their periodontal disease risk, however, the mechanism for this immunocompromised response is unique.

Diabetes causes multiple systemic disturbances, including the dysregulation of the innate immune system and an increase in the inflammatory response. Patients with HIV experience a much morse specific disturbance of the adaptive immune system. While periodontitis is common among both groups, the body’s response to the disease and the therapies aimed at treating it can be quite different. Understanding these differences is critical to providing the most effective periodontal care.

THE HUMAN BODY’S DUAL IMMUNE SYSTEMS

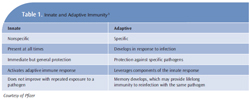

The human body is armed with two major systems of immunity—the innate and the adaptive immune systems (Table 1).3 The innate immune system is the one that humans are born with. The body uses this system immediately after exposure to almost any microbe in order to prevent infection. Unlike the adaptive immune system, the innate system does not recognize every possible invader. It is designed to recognize certain essential molecules that are shared by a number of related pathogenic microbes.4 The innate immune system response does not improve with repeated exposure to a particular pathogen.4 The adaptive immune system develops throughout life. It reacts to specific foreign invaders, also known as antigens (antibody generators), by binding them with B-cell (B-lymphocytes) secreted antibodies. This antibody binding marks the invading pathogen, making it easier for the innate immune system’s phagocytic cells to destroy them.4

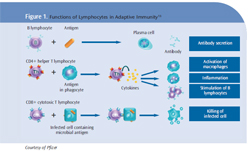

Additional groups in the cell-mediated adaptive immune response are activated T-lymphocytes or T-cells and T-helper cells. T-cells react against foreign antigens. In order for the adaptive immune system to be effective, the body develops massive numbers of T-cell and B-cell clones that allow the system to recognize the antigens it may encounter.4 This system improves with repeated exposures to a given stimuli or antigen. The ability to distinguish foreign from self is a fundamental feature of the adaptive immune system. Failure to recognize self can lead to destruction of the host’s own molecules as is the case in type 1 diabetes when the beta cells of the pancreas are destroyed.4

DIABETES AND THE INNATE IMMUNE SYSTEM

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder that leads to a number of complications, including the dysregulation of the innate immune system and a heightened inflammatory response. This dysregulation leads to the excessive formation and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in tissues and is one of the most common causes of diabetic complications.5 The presence of bacteria in the periodontal pocket triggers the innate immune system to send neutrophils in an attempt to phagocytize the invading bacteria and initiate a rapid inflammatory response.6

When micro-organisms overcome this first line of defense, a second line is activated in the innate immune system, which includes macrophages, lymphocytes, and cytokines.6 It appears that AGEs may be deposited on polymorphonuclear cells that produce a hyper-inflammatory state, which amplifies the body’s response to cytokines released upon contact with an antigen.7 These activated neutrophils show a heightened response upon contact with the lipopolysaccharide of Gram-negative bacteria, such as the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis found in subgingival biofilm.8 This heightened neutrophil behavior consequently triggers an exaggerated inflammatory cascade, which increases the destruction of periodontal connective tissue.8

DENTAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR PATIENTS WITH TYPE 2 DIABETES

Periodontal disease is one of many known complications of diabetes.1 The effect of diabetes on the innate immune system is thought to play a major role in the progression of periodontal disease, in part, through the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.9 The process by which diabetes contributes to this increased virulence of periodontal disease is complex and continues to be investigated. Resulting complications include enhanced gingival bleeding, increased loss of attachment, greater pocket depth formation, increased loss of alveolar bone, and poor wound healing.10 The presence of opportunistic infections, such as oral candidiasis, may also be a manifestation of systemic immuno supression associated with diabetes.11

Practitioners must be aware of these effects on nonsurgical and surgical periodontal treatment modalities. While uncontrolled diabetes is an absolute contraindication to elective procedures, even with good control, delayed wound healing is expected. This is due to diabetes-induced hypoxia, dysfunction in fibroblasts and dermal cells, impaired angiogenesis, and other factors including damage from AGEs and decreased host immune resistance.9 If periodontal or other oral surgery is planned, positive glycemic control will support better healing and treatment response. A number of criteria are available to help determine this. The HbA1c test for glycated hemoglobin is the best indicator of long-term diabetes control.11 Response to initial nonsurgical scaling and root planing may help predict outcomes and prognosis of subsequent treatment, including post-surgical healing.12

Treating patients with diabetes necessitates a focus on prevention, aggressive treatment planning as opposed to watching and waiting, meticulous follow-up care, and consistent communication with other members of the patient’s health care team. Oral infections must be treated immediately and consistent recare is required.11

HIV AND THE ADAPTIVE IMMUNE SYSTEM

HIV infection affects the adaptive immune system and is more specific than the generalized disruption of the innate immune system seen with diabetes. HIV-related disruption affects the T-lymphocyte branch of the immune system, destroying CD4+ T-helper cells.2 The terms “T-cell” and “CD4 cell” are used interchangeably because they refer to the same type of cell and, while there are many different types of T-cells, these particular cells have a specific receptor site on their surface called the CD4 receptor site. HIV uses this particular receptor to latch on to the T-cell, making it a prime target for infection (Figure 1).2,13In the face of infection, the adaptive immune system generates a population of “memory” B-cells that quickly mount an antibody response if the invading antigen is encountered again.4 HIV infection creates an unusual population of exhausted and nonresponsive B-memory cells, which diminish the immune response. When faced with an HIV infection, the body usually mounts a strong antibody response. Initially, the viral load diminishes significantly. It is thought that the production of nonresponsive B-memory cells allows the HIV to reassert itself, thus leading to increasing numbers of HIV. The infection is allowed to continue and may, eventually, overwhelm the body’s ability to respond appropriately.14

DENTAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR PATIENTS WITH HIV

HIV positive patients may present with conditions such as acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, acute necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis, oral candidiasis, herpes simplex and zoster viruses, recurrent apthous ulcers, and chronic periodontitis.15 Research16 has shown that the degree of attachment loss is greater among HIV-infected patients with pre-existing chronic adult periodontal disease, particularly when CD4 counts drop below 200 cells/mm3.

Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1995, HIV disease has become a manageable chronic illness. HAART has become the standard of care in the treatment of HIV/AIDS and appears to have decreased the prevalence, severity, and course of associated periodontal disease. HAART therapy generally increases the CD4 cell count above 200 cells/mm3 and is thought to decrease inflammation and immune activation while exhibiting fewer side effects than previous antiretroviral therapies.17

Although there is still concern that periodontal surgical procedures, including scaling and root planing, may cause a systemic bacteremia (blood infection) and subsequent systemic infections, evidence18 supports the idea that the resultant bacteremia returns to normal in a short time among patients with a CD4 count above 200 cells/mm3. However, bacteremia may occur not only as a result of professional dental manipulation, but by routine daily activities such as eating, brushing, and other oral self-care procedures. Good oral hygiene and gingival health are associated with reduced risk of bacteremia, making continuing care especially important in this population.19,20

While HIV infection may initially lead to a particular depression of the adaptive immune system and subsequent increase in opportunistic infections, it does not appear to alter the overall ability of the body to heal, which is very different from diabetes. Research and review of treatment has demonstrated that HIV positive patients with CD4 counts above 200 cells/mm3 generally have normal healing times following periodontal surgery, including implant placement.21

CONCLUSION

Oral health practitioners must remain vigilant in their care of patients with diabetes and HIV infection. Through intraoral examination, dental professionals may be the first to recognize signs of systemic pathology. A patient’s health history may present clues indicative of undiagnosed diabetes. Additionally, poor response to periodontal treatment, even in the face of ideal self-care, may raise the practitioner’s suspicions.

While simple in-office testing for blood sugar levels and HIV infection22 are available, referral to a physician for testing and diagnosis may be the first line of care for the patient who is not receiving routine medical care. All possible risk factors must be weighed when diagnosing and treating each patient. Periodontal treatment plans created for patients with type 2 diabetes or HIV infection should be customized based on current medical and social history, appropriate lab test results, diagnosis of oral findings, and consideration of current evidence. Understanding patients’ current medical status will help ensure the provision of the safest, most efficient, and effective dental care possible.

REFERENCES

- Mealey BL, Oates TW, American Academyof Periodontology. Diabetes mellitus andperiodontal diseases. J Periodontol.2006;77:1289–1303.

- Centers for Disease Control andPrevention. HIV in the United States.Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/PDF/us.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2012.

- Murphy K, Traver P, Walport M. Basicconcepts in immunology. In: Janeway’s Immunobiology. 7th ed. New York: Garland Science; 2008:1–108.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M,Roberts K, Walters P. Molecular Biology of theCell. 4th Edition. New York: Garland Science;2002.

- Vlassara H. Recent progress in advancedglycation end products and diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1997;46(Suppl):S19–S25.

- Offenbacher S. Periodontal diseases:pathogenesis. Ann Periodontol.1996;1:821–878.

- Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a two-way relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:51–61.

- Bascones-Martinez A, Matesanz-Perez P,Escribano-Bermejo, M, Gonzalez-Moles MA,Bascones-Ilundain J, Meurman JH.Periodontal disease and diabetics—review ofthe literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal.2011;16:e722–729.

- Guo S, DiPietro LA. Factors affectingwound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–229.

- Salvi G, Beck J, Offenbacher S. PGE2, IL-1and TNF- responses in diabetics as modifiers of periodontal disease expression. AnnPeriodontol. 1998;3:40–50.

- Ship JA. Diabetes and oral health: anoverview. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(Suppl):4S–10S.

- Lalla E, Hsu WC, Lamster IB. Dental andmedical co-management of patients withdiabetes. In: Genco RJ, William RC, eds.Periodontal Disease and Overall Health:A Clinician’s Guide. Yardley, Pa: Professional Audience Communications Inc; 2010:224.

- Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A. Diseases of the immune system. In: Robbins and Coltran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed.Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:1–15.

- Kardava L, Moir S, Ho J, et al. Attenuationof HIV-associated human B cell exhaustion by siRNA down regulation of inhibitory receptors.J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2614–2624.

- Winkler JR, Murray PA, Grassi M,Hammerle C. Diagnosis and management ofHIV-associated periodontal lesions. J Am DentAssoc. 1989;(Suppl):25S–34S.

- Yeung SC, Stewart GJ, Cooper DA,Sindhusake D. Progression of periodontal disease in HIV seropositive patients.J Periodontol. 1993;64:651–657.

- Parveen Z, Acheampong E, Pomerantz RJ,Jacobson JM, Wigdahl B, Mukhtar M. Effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy on HIV-1-associated oral complications. Curr HIV Res.2007;5:281–292.

- Lucartorto FM, Franker CIC, Maza J. Postscaling bacteremia in HIV-associated gingivitisand periodontitis. Oral Med.1992;73:550–554.

- Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Thornhill M, etal. Poor oral hygiene as a risk factor for infective endocarditis–related bacteremia.J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;3:20–26.

- Roda RP, Jiminez Y, Carbonell E, Gavalda C,Munoz MM, Perez GS. Bacteremia originating in the oral cavity. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:355–362.

- Kolhatkar S, Khalid S, Rolecki A, Bhola M,Winkler JR. Immediate dental Implant placement in HIV-positive patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: a report oftwo cases and a review of the literature of implants placed in HIV-positive individuals. J Periodontol. 2011;82:505–511.

- FDA. Vaccines, Blood and Biologics.Available at:www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/BloodBloodProducts/ApprovedProducts/PremarketApprovalsPMAs/ucm310436.htm.Accessed August 7, 2012.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2012; 10(9): 46-49.