Treating the EDS Patient

Patients with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome have specific oral implications that must be understood in order to safely treat them in the dental office.

This course was published in the April 2009 issue and expires April 2021. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

- Discuss the dental manifestations associated with EDS.

- Describe the clinical management of a dental patient with EDS.

Patients with EDS have very specific oral implications that dental professionals must be aware of in order to provide safe dental care. Appropriate referrals to other health care professionals may also be necessary.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

EDS was noted as early as 400 BC by Hippocrates with descriptions of “lax of joint” and “multiple scars.” Formal reports of EDS began in 1657 by Van Meekeren, a surgeon, who described the hyperelasticity of the skin of a sailor. It was later characterized in 1901 by a Danish dermatologist, Edward Ehlers, and in 1908 by a French dermatologist, Henri-Alexandre Danlos.1 By the 1930s the condition had been assigned the name Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Early descriptions of the syndrome began with insensitive terminology like “elastic man,” “the human pretzel,” or “rubber woman.”2 The conditions of the syndrome are so unusual that people with EDS have displayed their symptoms in circuses and other such shows.

DEFINITION

EDS is a heterogeneous and multisystemic collection of inherited disorders that directly affects collagen structure and function.2,3Collagen is a fibrous protein that provides integrity, strength, and elasticity to connective tissues. Skin, muscles, ligaments, organ walls, cartilage, bone, and blood vessels all require collagen to meet their specific functions and purpose within the body.

PREVALENCE

According to recent statistics by the Ehlers-Danlos National Foundation, one in 5,000 to one in 10,000 people are currently affected by some form of the syndrome.4 EDS has been documented throughout the world without gender, racial, or ethnic associations.1,2,5

CLASSIFICATION

The classification of EDS began in the late 1960s followed by a formalized nosology (classification of diseases) in 1997 to serve as guidelines for diagnosis and management.3 Currently, EDS can be classified into eight major groups according to the symptoms presented by the patient (Table 1). The most common types are classical, hypermobility, and vascular, while kyphoscoliosis, arthrochalasis, dermatosparaxis, and chromosome X types are rare.6 The periodontal type is similar to the classical type with the presence of periodontal issues.

INHERITANCE PATTERNS

There are two known inheritance patterns that have a role in the disorder: autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive (Table 1). Autosomal dominant inheritance (classical, hypermobility, vascular, and arthrochalasia types) exists when one parent has an abnormal gene pair (one functioning, one mutant). There is a 50% possibility with each pregnancy that the child will receive the mutant gene. On the other hand, kyphoscoliosis and dermatosparaxis types are inherited as autosomal recessive. In autosomal recessive inheritance, both parents have an abnormal gene pair. There is a 25% chance the child will receive the common recessive gene from both parents, subsequently acquiring EDS.4

Family history determines the type and severity (mild, moderate, severe) of the syndrome. A mother with hypermobility type, for example, could have a child with hypermobility type, but not arthrochalasis type.1,2,4,5

DIAGNOSIS

Most diagnoses of EDS are based on clinical findings and family history. A confirmed laboratory diagnosis can only be made in four types (vascular, kyphoscoliosis, arthrochalasia, and dermatosparaxis) through biochemical and molecular tests, skin biopsies, and prenatal testing.1,2,5

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

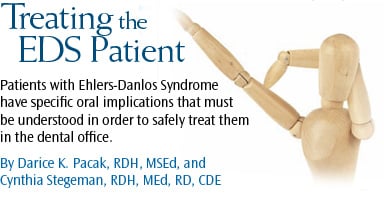

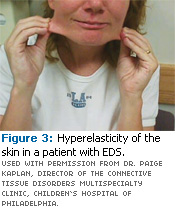

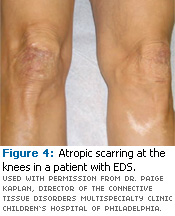

Physical characteristics of EDS include joint hypermobility (Figures 1 and 2); joint dislocation; hyperelasticity of the skin (Figure 3); soft, velvet-like, thin, and fragile skin; atrophic scarring (described as “cigarette-paper” scars) at pressure points, such as knees (Figure 4), elbows, shins, and forehead; a tendency toward excessive bleeding; spontaneous arterial rupture; easy bruising with a brown discoloration; and ecchymosis and hematomas.1,2,5,6,7 The patient may experience musculoskeletal pain. In addition, extraoral signs documented by a dental professional may involve large, widely spaced eyes; small corneas; a thin nose; lobeless ears; short stature; club feet; and thin hair.2,5,7 The medical history of a patient with EDS may include scoliosis, osteopenia, and shortened bones.2,7

DENTAL IMPLICATIONS

A direct correlation exists between EDS and generalized aggressive periodontitis and several other oral manifestations.7 A thorough assessment, including an intra- and extraoral examination, can identify some of the physical and oral characteristics of EDS. This will alert the practitioner to clinical precautions that may need to be considered when treating patients with this syndrome.

Of particular interest to the dental hygienist is the link between periodontal EDS (type VIII) with oral and maxillofacial conditions.1 Aggressive generalized periodontitis is one of the single most significant oral manifestations of EDS. In turn, this relationship frequently results in clinical attachment loss, tooth mobility, root resorption, and/or loss of teeth (deciduous and permanent).8 Early management of periodontal complications is recommended.

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMJ) is related to the hypermobility of the joint. It is thought to be associated with the excessive mobility of the discs and looseness of the ligaments related to abnormal collagen formation.9 Repeated subluxations of the TMJ along with pain, trismus, crepitus, and clicking of the TMJ may also be present.1,5,7

Oral manifestations can include a fragile mucosa in the floor of the mouth, ventral surface of the tongue, inside of the lips or soft or hard palate, and gingiva. Fragile mucosa can tear easily when manipulated during orthodontic treatment, dental instrumentation, the eating of hard foods, and aggressive oral selfcare, which will cause excessive gingival bleeding.1,2,5 This is a concern due to the prolonged and deficient tissue healing of patients with EDS.

Radiographic observations frequently show pulpal calcifications and abnormal pulp shape; abnormal root morphology (short, deformed, and dilacerated); and dentin that contains structural irregularities.1,2,5 These have the potential to compromise endodontic treatment. Other oral conditions that can be present include hypoplasia of the enamel, deep fissures, and long cusps in premolar and molar teeth, microdontia, and the presence of supernumerary teeth.1,2,5

The periodontal ligament space is very fragile, so fewer forces are required for orthodontics.1,2,5 The teeth move very rapidly with regular forces. Treatment of orthodontics should proceed slowly and with caution because of the fragile state of the periodontal ligament and mucosa and the increased risk of tooth resorption and tooth loss.1,2,7,8 Relapse is frequently seen in orthodontic cases and a longer period of treatment is recommended.1,2

Scarring and hematomas can easily occur from slight trauma.1,2,5 In addition, absence of the inferior labial and lingual frena, slow or poor wound healing, and vascular abnormalities due to the impaired extracellular matrix structure may exist in patients with EDS. Oral observations frequently include a vaulted palate and/or a supple tongue. Approximately 50% of those with EDS can touch the end of their nose with their tongue (Gorlin’s sign).2

TREATMENT PLANNING

Currently there is no cure for EDS. The American Dental Association and the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons do not have a specific standard of care for prophylaxis or peri-operative hemorrhagic control for EDS patients at the present time.1 Since the patient with EDS will vary in symptoms and severity, the dental hygienist should use reasonable judgment when planning and treating patients with EDS.

EDS patients should be instructed on meticulous and gentle oral hygiene care, using modified brushing techniques with ultrasoft toothbrushes. The high plaque index of many patients with EDS may be related to difficulties with oral self-care from chronic pain in the hands or arms, restricted joint mobility, or concern of excessive bleeding from fragile mucosa.5 Frequent dental recare appointments should be recommended to prevent complications or detect issues early. To avoid tissue trauma during recare appointments, careful instrumentation and minimal use of ultrasonic scaling instruments are recommended. Patient positioning in the dental chair should be accommodated according to patient need for enhanced comfort.

Nutrition is an important component of the management of EDS. Patients with EDS need to consume the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of vitamin C, which helps collagen synthesis and enhances wound healing. The RDA is 90 mg per day for men and 75 mg for women, which can usually be met by consuming one serving per day of foods high in vitamin C such as citrus fruits, cantaloupe, green and red peppers, broccoli, and strawberries. The recommendation for vitamin C may be increased when patients are faced with stress, healing, infections, and drug use (tobacco, alcohol, and oral contraceptives). An addition of 35 mg per day may be beneficial in these situations. The tolerable upper intake (UL) is 2,000 mg/day. Intakes exceeding this may result in gastrointestinal distress, diarrhea, and interfere with vitamin B12 absorption.10

Nutritional counseling by the dental hygienist regarding adequate dietary intake should be a component of the treatment plan, using the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 (www.healthierus.gov/dietary guidelines) and the MyPyramid Food Guidance System (http://mypyramid.gov). More complex nutritional concerns should be referred to a dietitian.11

EDS patients tend to have a higher incidence of caries. An assessment of the patient’s carbohydrate consumption behaviors and dietary counseling are warranted. Encouragement of meticulous oral self-care is also needed.

Office visits should be kept short to prevent dislocation of the TMJ.1,2 When administering local anesthesia, caution should be given due to the possibility of causing a hematoma.1,2 Oral and maxillofacial surgery should be avoided if possible.2

CONCLUSION

EDS affects the tissues of the oral cavity, as well as many other systems of the body. A thorough assessment of the patient can lead to the recognition of the signs of EDS and early referral of the patient. Having the information prior to treatment allows the dental hygienist to synthesize a tailored plan for optimal patient care, as dental procedures must be performed with caution in this patient population. In addition, consultation with other health care professionals is necessary.

REFERENCES

- Abel MD, Carrasco LR. Ehler-Danlos syndrome: classifications, oral manifestations, and dental considerations. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol, Oral Radiol, Endod. 2006;102:582-590.

- Létourneau Y, Pérusse R, Buithieu H. Oral manifestations of Ehler-Danlos syndrome. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:330-334.

- Beighton P, De Paepe A, Steinmann B, Tsipouras P, Wenstrup RJ. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Am J Med Genet. 1998;77:31-37.

- Ehler-Danlos National Foundation. Available at: www.ednf.org. Accessed January 23, 2009.

- De Coster PJ, Martens LC, De Paepe A. Oral health in prevalent types of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:298-307.

- Calewaert B, Malfait F, Loes B, De Paepe A. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and Marfan syndrome. Best Prac Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:165-189.

- Moore MM, Votava JM, Orlow SJ, Schaffer JV. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VIII: periodontitis, easy bruising, Marfanoid habitus, and distinctive facies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:S41-S45.

- Bandauy CM, Gomes SS, Filho MSA, Chies JAB. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) type IV. Review of the literature. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11:183-187.

- McDonald A, Pogrel MA. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: an approach to surgical management of temporomandibular joint dysfunction in two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:761-765.

- American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: fortification and nutritional supplements. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:1300-1311.

- Stegeman CA, Davis JR. The Dental Hygienists’ Guide to Nutritional Care. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier. In press.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2009; 7(4): 42-45.