Treating Patients with Cystic Fibrosis

As the number of adults living with this genetic disorder increases, dental hygienists should be prepared to provide individualized attention to this patient population.

This course was published in the September 2013 issue and expires September 2016. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the etiology of cystic fibrosis (CF), and list the disease’s characteristic effects and secondary conditions.

- Discuss available treatments, medications, and dietary recommendations for patients with CF.

- Explain the effect of CF on the dentition and oral tissue encountered findings in dental radiographs.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a life-shortening autosomal recessive gene disorder that affects the body’s secretory glands, which are responsible for supplying mucus and sweat.1,2 Affecting one in every 2,500 births per year,1 CF is the most common fatal recessive inherited disease among the Caucasian population in the United States. It is less common among other ethnicities.

Most healthy individuals have two working copies of the CF regulator gene.2 A person who has only one working copy and one mutated CF regulator gene caries CF, but does not have the disease.2 Rather, CF develops when a fetus inherits a mutated CF regulator gene from both the mother and the father.2 More than 1,500 types of mutations for the CF regulator gene exist, with mutations affecting individuals in singular patterns.1 The CF regulator gene defect, however, leads to a mutation in a chloride channel found in the epithelial tissues of the lungs, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and skin.2 This mutation affects the transport of salt and water across the epithelia, changing the viscosity of the mucus that lines these organs from watery and slippery to thick and sticky.2 Thick and viscous mucus results in blockages in the lungs, pancreatic ducts, and other organs, and also creates an environment that facilitates overgrowth of bacteria in the affected tissues.2

Advancements in treatments have positively affected life expectancy for individuals with CF. In 1987, the median survival age for people with CF was 27 years; the present median survival age is 40.1 Children with CF born today are expected to live more than 50 years.3 The four main approaches to CF treatment include: nutritional repletion; clearance of airway obstruction; addressing airway infection; and suppressing infection. Advances in these areas, such as better enzyme formulations and stronger, more target have made a difference in longevity. Lifespan among those with CF is related to genetics, environmental exposure, health care, and socioeconomic status (some of which cannot be controlled), and an increase in the knowledge base surrounding CF has helped this population live longer, healthier lives than ever before. Additionally, children with CF who maintain a healthy weight and have positive forced expiratory volume (amount of air that can be exhaled in 1 second) and forced vital capacity (maximum amount of air exhaled after deep inhalation) scores fare the best when it comes to life expectancy.3

The most common symptoms of CF include difficulty breathing and insufficient pancreatic enzyme production.1 Secondary conditions, such as CF-related diabetes and osteoporosis, may develop.1 CF is not curable; however, many of the symptoms and secondary conditions can be treated or prevented with medications, nutrition, exercise, and physical therapy. Dental hygienists can also play an important role in promoting the health of patients with CF.

THE LUNGS

CF causes thick and sticky mucus to build up in the lungs and airways. The irritation from thick mucus results in frequent coughing and, sometimes, the buildup of fluid containing blood.2 Over time, damage to the lungs increases and may lead to respiratory infection and failure. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death for individuals with CF.2 Thick mucus enables bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, to infect the lungs (Figure 1).2 Other common lung infections include pneumonia and bronchitis.2 For these reasons, medications, including long-term antibiotic treatment, inhaled drugs, and nebulizers, are typically used by individuals with CF.4

In addition to medications, chest physical therapy and exercise are common lung treatments. Chest physical therapy involves chest percussion to loosen mucus deposits (Figure 2). Loosened mucus may then be expectorated.2,4 Aerobic exercise to increase heavy breathing helps loosen the mucus in the airways prior to expectoration. Since CF causes loss of sodium via increased exercise induced perspiration, an increase in dietary salt may be indicated.2 Caution must be taken while exercising, as the loss of salt can lead to dehydration, increased heart rate, fatigue, weakness, decreased blood pressure, heat stroke, and, rarely, death.2

EXOCRINE PANCREATIC INSUFFICIENCY

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is present in 85% of individuals with CF.5 The pancreas normally secretes digestive enzymes (lipase, protease, and amylase) into the duodenal lumen where the breakdown of nutrients occurs.5 Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is characterized by maldigestion, malnutrition, weight loss, flatulence, and foul-smelling, loose stools.5 These clinical symptoms are primarily due to problems digesting fat.5

Inadequate treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency can have serious consequences on nutritional status, lung function, and survival.5 Treatment for this condition includes receiving pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, which allows for efficient fat and nitrogen absorption and improvement in clinical symptoms and body weight.5

In the absence of the pancreatic enzymes necessary to breakdown nutrients, the intestines are unable to efficiently absorb fats and proteins, resulting in vitamin deficiency and malnutrition. Individuals with CF present with poor growth and low weight gain, due to nutritional deficiency. Optimal nutritional status is essential from infancy.6 By age 4, children with CF within the 50th percentile for weight demonstrate healthier lung function, increased life expectancy, spend fewer days in the hospital, and grow taller than individuals with CF whose weight registers in the less than 50th percentile.6 In addition, the risk of developing CF-related diabetes is up to five times greater in individuals with CF who have experienced severe early malnutrition.6

DIABETES

CF-related diabetes presents in 20% of adolescents, and 40% to 50% of adults with CF.9 CF-related diabetes shares some common features of type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes, but is different enough to warrant a distinct classification.7 Type 1 diabetes is characterized by the complete absence of insulin production, while type 2 is related to insulin resistance. CF-related diabetes is a combination of insulin deficiency and insulin resistance.7 Individuals with CF related diabetes experience severe pulmonary disease, pulmonary exacerbations, high prevalence of sputum pathogens, low nutritional measurements, and a high prevalence of liver disease.7 Mortality rates are higher among those with CF-related diabetes than those with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, though these data have recently improved due to routine blood glucose screening and aggressive treatment with insulin.7 All patients with CF have exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, although only a percentage present with CF-related diabetes. The reason for this is unclear.7

OSTEOPOROSIS

CF does not cause osteoporosis, however, osteoporosis can result from multifactorial clinical manifestations. Malabsorption of vitamin D, poor nutritional status, physical inactivity, glucocorticoid therapy, and delayed pubertal maturation all contribute to osteoporosis.8 Decreased quantity and quality of bone mineral resulting from these factors can lead to pathological fractures decades earlier than expected.8 Severe bone disease can exclude patients from becoming candidates for lung transplantation, often a life-saving operation.8 The prevalence of bone disease increases with the severity of lung disease and malnutrition.8 Prevention, early recognition, and effective treatment recommendations are the most predictable strategies for maintaining bone health.8

NUTRITIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS

Ample caloric nutrition to control several facets of CF is required. High-fat, high-carbohydrate diets and between-meal snacks are often prescribed for individuals with CF.2,4,6 Supplementation of vitamins A, D, E, and K may be taken to replace malabsorption of the fat-soluble vitamins in the intestines. In some instances, a feeding tube to deliver extra calories may be used during sleep.2,4 Other treatments for nutritional deficiency may include reducing intestinal blockages with enemas and mucus-thinning medicines.2

ORAL IMPLICATIONS

Individuals with CF follow a high-fat, high carbohydrate diet, and dental hygienists may expect to see tooth decay; however, reports of caries rates in individuals with CF conflict. Several studies have reported that individuals with CF present with a low caries prevalence.9-13 However, a recent systematic review of dental caries prevalence in children and adolescents with CF reported a reduced risk for dental caries among children with CF, and a potentially increased risk for caries among adolescents with CF.14 In addition, individuals with CF are more likely to develop enamel defects.15 More than 90% of individuals with CF have at least one enamel defect, including demarcated opacities, diffuse opacities, and enamel hypoplasia.15 Although early studies reported that individuals with CF had less plaque than those without CF,13 more recent studies have shown that the plaque levels tend to be the same among both groups.10-12 Studies have also shown that those with CF experience fewer gingival bleeding sites than people without CF.9-12 Patients with CF are at an increased risk of candidiasis, due to the use of inhaled steroids and long-term antibiotic regimens, and from the effects of CF-related diabetes.16,17

There are several theories as to why individuals with CF may be at reduced risk of dental caries and periodontal diseases. In regards to the decreased caries rate, one hypothesis suggests that the natural pH buffering effects created by consuming a diet high in dairy products protects the dentition from decay.9,11 Another theory purports that because patients with CF undergo long-term antibiotic regimens (in addition to pancreatic enzymes), they may be less likely to develop caries and gingival bleeding, as these agents can change the microbial flora in the mouth.9-13 Azithromycin is frequently prescribed for individuals with CF, and it is particularly effective against Gram-negative bacteria.4 Azithromycin is able to penetrate dental biofilm, has good periodontal tissue penetration, and is retained in the periodontal pocket for up to 14 days.18 Additionally, individuals with CF have altered salivary content with higher calcium and phosphate concentrations, which may increase the saliva’s buffer capacity.9,11-13 A possible explanation for the potential increase in dental caries among adolescents with CF is that the new generation of antibiotics, which targets Pseudomonas aeruginosa, does not affect Streptococcus mutans. Therefore, adolescents with CF may lose the caries protective benefits experienced in childhood.14

PROCESS OF CARE

Dental hygienists promote oral health and use scientific-based research to attain knowledge. Lifelong learning involves developing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that support a value for overall health.19 When a patient with CF presents for dental care, the six components of the dental hygiene process of care—assessment, dental hygiene diagnosis, planning, implementation, evaluation, and documentation—should be addressed. Patients with CF typically have medical evaluations every 3 months.2 Therefore, health history updates should be thorough and used to determine health status, lung function, history of hospitalizations, contraindications to care, and need for medical consultation at continuing care appointments.

Changes in medications are possible, and the medication history should always be updated. Blood pressure should be taken at the initial dental hygiene appointment to identify hypertension.20 Blood pressure should be checked at subsequent dental hygiene visits.21 If a patient has CF-related diabetes, blood glucose levels should be monitored for disease control and to identify the risk for hypoglycemia, a common medical emergency among those with diabetes.20 Patients with CF should be screened for candidiasis, caries, and periodontal diseases.19 Dental hygienists should also assess patients with CF for disease control, nutritional status, and status of their oral hygiene regimens.

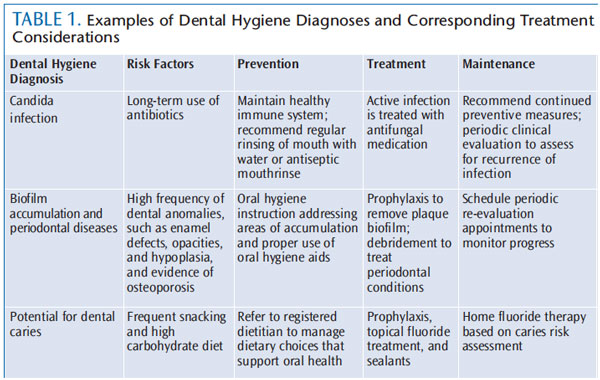

According to the American Dental Hygienists’ Association, “The dental hygiene diagnosis is the identification of an existing or potential oral health problem that a dental hygienist is educationally qualified and licensed to treat.”19 Dental hygienists should analyze all data collected during assessments to recognize potential or actual problems.19 This information can be used for patient information and medical consultations.19 Table 1 provides examples of dental hygiene diagnoses, and corresponding treatment considerations.

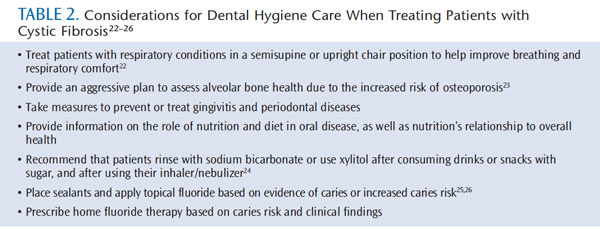

The care plan may include interventions such as referrals, oral hygiene instruction, nutritional counseling, and periodontal maintenance. Appointment scheduling needs to be flexible because patients with CF may be spending several hours per day receiving breathing treatments and keeping other medical appointments. Dental hygienists should begin the treatment plan with the patient’s goals in mind. Table 2 lists specific considerations that should be taken when treating patients with CF.22–26

Evaluation of patients with CF is similar to that required for all patients. At the periodontal maintenance appointment, oral conditions should be assessed and further treatments recommended. The dental hygienist’s findings at the evaluation appointment may lead to a new diagnosis, revised goals, and alternative interventions. Thorough documentation is essential for patients with CF because there are many different health care professionals involved with their care. Documentation serves as a communication tool, provides a guideline for consistent care and accountability, and protects both the patient and the dental hygienist.19

TREATING PATIENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Patients with special needs may require adaptation to experience successful dental hygiene appointments. Appointment times, appointment length, chair position, which operatory to provide treatment in, background noise (such as music or movies), and the choice of dental hygiene instruments should all be adjusted to suit individual patient needs. Many children with special needs have sensory issues, require wheelchair transfers, take oxygen supplementation, and may exhibit behavioral issues, which can make the provision of dental hygiene care challenging. Dental hygienists should consider alterations in management of care while taking the medical and dental history, and be prepared to modify the traditional delivery of dental hygiene treatment.

Oral hygiene care recommendations need to address patients’ unique needs.25 Individuals with special health care needs may be at an increased risk for oral diseases throughout life, which can have a direct and devastating impact on the health and quality of life.25 Failure to accommodate patients with special health care needs is considered discrimination and a violation of the law.25 Patients with special needs experience fear, anxiety, and stress regarding dental appointments.2 Dental hygienists should speak directly to patients and demonstrate empathy to help establish rapport. Communication with patients should be in a language appropriate for age, culture, and learning style.18

CONCLUSION

Goals of CF treatment include preventing and controlling lung infections, treating exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and managing any complications or secondary conditions that may result from this disease. A team of health care providers can work together to provide optimal health care for individuals with CF. Dental hygienists can be a valuable team member in providing care to promote oral and overall health. While the prevalence of CF remains steady, more adults than ever before are living with this disease.1 Dental hygienists need to be prepared to provide excellent dental hygiene care specifically tailored to this patient population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- DAVID MACK / SCIENCE SOURCE

- FIGURE 1. SIMON FRASER / SCIENCE SOURCE

- FIGURE 2. WILL & DENI MCINTYRE / SCIENCE PHOTO

REFERENCES

- Leitch AE, Rodgers HC. Cystic fibrosis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2013;43:144?150.

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.What Is Cystic Fibrosis? Available at:www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/healthtopics/topics/cf/. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Simmonds NJ. Cystic fibrosis and survivalbeyond. Annals of Respiratory Medicine.2011;2(1):55–61.

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Therapies forCystic Fibrosis. Available at: www.cff.org.Accessed August 27, 2013.

- Kuhn RJ, Gelrud A, Munck A, Caras S. CREON(Pancrelipase Delayed-Release Capsules) for the treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Adv Ther. 2010;27:895?916.

- Yen EH, Quinton H, Borowitz D. Betternutritional status in early childhood isassociated with improved clinical outcomesand survival in patients with cystic fibrosis. JPediatr. 2013;162:530?535.

- Laguna TA, Nathan BM, Moran A. Managingdiabetes in cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Obes Metab.2010;12:858?864.

- Aris RM, Merkel PA, Bachrach LK, et al.Guide to bone health and disease in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2005;90:1888–1896.

- Aps JK, Van Maele GO, Martens LC. Oralhygiene habits and oral health in cystic fibrosis. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2002;4:81?187.

- Ferrazzano GF, Orlando S, Sangianantoni G,Cantile T, Ingenito A. Dental enamel defects inItalian children with cystic fibrosis: an observational study. Community Dent Health.2012;29:106-–109.

- Aps JK, Van Maele GO, Martens LC. Cariesexperience and oral cleanliness in cysticfibrosis homozygotes and heterozygotes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod.2002;93:560–563.

- Narang A, Maguire A, Nunn JH, Bush A.Oral health and related factors in cystic fibrosis and other chronic respiratory disorders. ArchDis Child. 2003;88:702–707.

- Kinirons MJ. The effect of antibiotic therapy on the oral health of cystic fibrosis children. IntJ Paediatr Dent.1992;2:139–143.

- Chi DL. Dental caries prevalence in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: aqualitative systematic review and recommendations for future research. Int JPaediatr Dent. 2013;23:376–386.

- Azevedo TD, Feijo GC, Bezerra AC. Presence of developmental defects of enamel in cystic fibrosis patients. J Dent Child (Chic).2006;73:159–163.

- Chotirmall SH, Greene CM, McElvany NG.Candida species in cystic fibrosis: A road less travelled. Med Mycol. 2010;48(Suppl 1):114–124.

- Gammelsrud KW, Sandven P, Hoiby EA,Sandvik L, Brandtzaeg P, Gaustad P. Colonization by Candida in children with cancer, children with cystic fibrosis, and healthy controls. ClinMicrobiol Infec. 2011;17:1875–1881.

- Hirsch R. Periodontal healing and boneregeneration in response to azithromycin. Aust Dent J. 2010;55:193–199.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association.Standards For Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice.Available at: www.adha.org/resourcesdocs/7261_Standards_Clinical_Practice.pdf.Accessed August 27, 2013.

- Pickett FA, Gurenlian JR. Preventing MedicalEmergencies: Use of the Medical History. 2nd Ed.Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2010:1–19.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood PressureInstitute. The Seventh Report of the JointNational Committee on Prevention, Detection,Evaluation, and Treatment of High BloodPressure. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2013.

- Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL.Pulmonary Disease. In: Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 8th ed. St.Louis: Elsevier Inc; 2013:93–118.

- Redlich K, Smolen JS. Inflammatory boneloss: pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention.Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:234?250.

- Featherstone JBD. Dental caries management by risk assessment. In: Darby ML,Walsh M, eds. Dental Hygiene Theory andPractice. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier;2010:284?304.

- Beauchamp J, Caufield PW, Crall JJ, et al.Evidence-based clinical recommendations for the use of pit and fissure sealants: a report of the American Dental Association Council onScientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc.2008;139:257?268.

- American Dental Association Council onScientific Affairs. Professionally applied topical fluoride: evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc.2006;137:1151?1159.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2013; 11(9): 63–67