Treating Patients with Bell’s Palsy

Individuals with this type of facial paralysis often experience negative oral health effects.

Dental hygienists learn about a variety of conditions that affect oral health in the course of their clinical education, some of which are rarely encountered in private practice. While Bell’s palsy—a paralysis that affects the muscles responsible for facial expressions—is not common, it does negatively impact oral health. Dental professionals should be prepared to identify the signs and symptoms of Bell’s palsy, as well address its effects on the oral cavity.

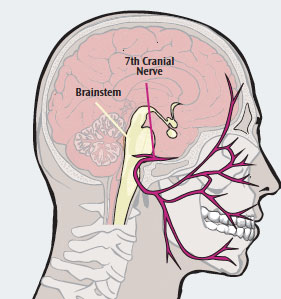

Bell’s palsy, named after 19th century anatomist Charles Bell, is a condition characterized by acute facial paralysis.1 Patients affected by this condition experience a sudden weakness on one side of the face that causes the muscles to droop (Figure 1). The condition results in damage to the facial, or 7th cranial nerve (Figure 2).1 Between 30,000 to 40,000 people in the United States are impacted by Bell’s palsy, which may occur at any age.1

The exact cause of the cranial nerve damage that results in Bell’s palsy is unclear.1 One theory is that the nerve is compressed as it passes through the fallopian canal, from the internal acoustic meatus to the stylomastoid foramen of the temporal bone in the skull.1,2 Symptoms often occur overnight and range from mild to severe, peaking within 3 days to 1 week. The signs of Bell’s palsy, such as a drooping face, are similar to stroke, which can interfere with the diagnostic process. In addition, the eye on the affected side will be difficult to close and the corners of the mouth will sag.3 Patients may also experience a loss of taste sensation in the anterior part of the tongue and have difficulty smiling or making facial expressions. Numbness or twitching may occur on the affected side of the face, accompanied by pain in or behind the ear.3 Bell’s palsy is not permanent, with symptoms usually disappearing within several weeks of onset.1

RISK FACTORS

A specific cause for Bell’s palsy has not been established.4 The scientific literature includes several possible theories about its etiology, including exposure to a viral infection—specifically the herpes simplex virus.1 A direct association between the herpes virus and Bell’s palsy, however, has not been demonstrated.5

Pregnant women in the third trimester, mothers who have recently given birth, and individuals recovering from upper respiratory infections, such as cold or flu, are at greatest risk for Bell’s palsy.4 It is also associated with flu-like symptoms, headaches, middle ear infection, high blood pressure, diabetes, Lyme disease, and facial trauma.1 Research on a definitive cause for Bell’s palsy is ongoing.

DIAGNOSIS

A thorough medical history is necessary to diagnose Bell’s palsy. Without an available laboratory test for diagnosis, a differential diagnosis is usually needed. Electromyography (EMG) and imaging scans may be useful.4 The EMG can confirm the presence and severity of nerve damage. Imaging scans, such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, may be needed to rule out other potential causes of pressure on the facial nerve (ie, tumor or skull fracture).4 It is important to reassure patients that Bell’s palsy is not related to stroke, which would most likely impact the arms and legs of the affected side, in addition to the face. Patients who experience sudden weakness on one side of the face should seek medical care immediately to rule out other possible health problems.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Bell’s palsy affects every individual differently. In mild cases, symptoms resolve without treatment within 2 weeks. For moderate or severe cases of Bell’s palsy, certain medications can mitigate the symptoms. Corticosteroids, such as prednisone, may be beneficial in reducing inflammation and limiting nerve damage.6 They work best when implemented immediately after the symptoms first appear.

Antiviral medications have also been used to treat Bell’s palsy, due to a potential link between the condition and the herpes virus. There is little evidence, however, that demonstrates the effectiveness of antiviral medications in mitigating the symptoms of this condition.7 Applying moist heat and performing physical therapy exercises may help restore full muscle function, though more clinical trials on the efficacy of these approaches are needed.8 In the past, surgery was used to relieve the pressure on the cranial nerve, but the evidence does not support this invasive approach, and it has been generally abandoned.9

Most people affected by Bell’s palsy will completely recover within 1 month to 2 months, with or without treatment. A small number of affected individuals will experience permanent muscle weakness. Bell’s palsy can recur for unknown reasons, and may affect the same or opposite side of the face.1

CONSIDERATIONS FOR DENTAL PROFESSIONALS

Bell’s palsy can cause negative oral health effects. Nerve damage may result in the overproduction or reduced production of tears and saliva.3 Patients with decreased salivary flow may experience xerostomia, which increases the risk for dental caries.10 There are a number of products available to address the effects of xerostomia, including those containing fluoride, calcium phosphate technologies, antimicrobials, sodium bicarbonate, and xylitol.11 These products can increase lubrication and decrease the loss of minerals from tooth surfaces by improving the buffering ability of saliva.11 Due to the increased risk of caries in this population, dental hygienists may want to consider these strategies, as well as the application of fluoride varnish and/or prescription home-based fluoride therapies.

Patients may develop angular cheilitis as a result of muscle tone loss and excessive drooling, which can be treated with antifungal medications.4,10 The loss of muscle tone on the affected side may interfere with the patient’s ability to chew food.4 Food can also become trapped in the vestibule of the cheek due to the impaired buccinator muscle that normally aids in moving food onto the occlusal plane.12 This may lead to an increase in dental biofilm accumulation. Dental hygienists, therefore, need to emphasize the importance of twice daily brushing and flossing to patients with Bell’s palsy. The addition of a therapeutic mouthrinse and irrigation with a dental water jet to the self-care regimen may be indicated. If flossing compliance is an issue, interdental brushes and flossing aids should be recommended. Patients also need to rinse with water after eating to remove food particles that may be trapped in the vestibule.12

The muscles surrounding the eye are impacted in Bell’s palsy, which results in difficulty closing the eyelid on the affected side.4 The eyelid may need to be taped closed at night, and protective eyewear must be used during dental treatment. Eye dryness or excessive tearing is common in Bell’s palsy.10 Dry eyes may be relieved with moisturizing eye drops.1

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists should be aware of Bell’s palsy and its resultant oral manifestations. Patients who present with facial paralysis should be examined by a medical provider to rule out more serious medical conditions. Dental hygienists’ can assist in managing the symptoms of Bell’s palsy and be a valuable resource for patients with this condition.

REFERENCES

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Bell’s Palsy Fact Sheet. Available at: ninds.nih.gov/disorders/bells/detail_bells.htm. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- Fehrenbach MJ. Herring SW. Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011.

- ADAM Medical Encyclopedia. Bell’s Palsy. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmedhealth/PMH0001777. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- Mayo Clinic. Diseases and Conditions: Bell’s Palsy. Available at: mayoclinic.com/health/bell-palsy/DS00168. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- Linder TE, Bodmer D, Sartoretti S, Felix H, Bossart W. Bell’s palsy: still a mystery? Otol Neurol. 2002;23(Suppl 15):abstract.

- Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Daly F, Ferreira J. Corticosteroids for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD001942.

- Allen D, Dunn L. Aciclovir or valaciclovir for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:CD001869.

- Teixeira LJ, Valbuza JS, Prado GF. Physical therapy for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD006283.

- McAllister K, Walker D, Donnan PT, Swan I. Surgical interventions for the early management of Bell’s palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD007468.

- Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Su N, Marek CL, Ching V, Grushka M. Caries prevention for patients with dry mouth. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:85.

- Fidanoski B. Bell’s Palsy (Facial Paralysis): Dental Hygiene Perspective. Available at: fidanoski.ca/dentalhygiene/2011/bellspalsy.htm. Accessed February 4, 2014.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2014;12(3):40,42