ZEPHYR/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

ZEPHYR/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

The Complexity Of Multiple Sclerosis

Patients with this neurodegenerative disorder need a customized dental care plan to maintain both oral and overall health.

This course was published in the December 2016 issue and expires December 31, 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the classifications for multiple sclerosis (MS).

- Discuss the diagnosis and treatment of MS.

- List strategies for helping patients with MS receive professional dental care.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disorder of the myelin sheath where plaques are created on the central nervous system (CNS) and alter nerve function.1 The exalammation is suspected.2 Progression of MS and new plaque formations lead to CNS changes in motor, sensory, and cognitivct cause of MS is unknown, but a combination of genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, immune system response, and systemic infe functions that create different degrees of symptoms and severity for each individual.2–4

MS is categorized into four groups according to type and severity of relapse and recovery. About 85% of MS diagnoses are relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).1–3 Individuals with RRMS experience symptom flare-ups, followed by periods of improvement where symptoms appear less severe.1 Relapses occur over a 24-hour to 96-hour period, last for days to weeks, and gradually resolve.5 Approximately 50% of relapses cause permanent damage to the CNS.1 As RRMS progresses and damage to the CNS becomes permanent, the disease can develop into secondary progressive MS.1 For most individuals with MS, disease progression and worsening of symptoms are a gradual process.3 Primary progressive (PPMS) and progressive-relapsing (PRMS) are rare and serious forms of MS, in which the disease onset is sudden and the neurological effects are significant.1 Medications successful in reducing inflammation and preventing further nerve damage in RRMS are not beneficial for PPMS or PRMS.1

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

MS most frequently occurs in white women ages 20 to 45, although anyone can be affected.1,2 Contributors to MS development and relapse include: infection; inflammation; presence of immune system disorders, common cold, and influenza; vitamin deficiencies; and smoking.2,6 New theories regarding the etiology of MS—such as genetic code changes, gut flora, and chronic stress—are currently under investigation.7,8

Common physical symptoms of MS are pain, vision problems, motor impairment, and fatigue.2,9 Severe symptoms include bladder and bowel problems, sexual dysfunction, concentration and memory problems, and depression.9 Facial pain—such as trigeminal neuralgia and partial facial paralysis or spasms, and difficulty with speech and swallowing—are frequently reported.2,9 As many as 64% of patients with MS experience paresthesia, dysesthesia, hyperesthesia, and anesthesia.9

Fatigue is the most ubiquitous complaint in individuals with MS.10 As many as 78% of patients experience severe fatigue that interferes with their activities of daily living.10 Among individuals with MS, 50% to 60% experience depression and 25% to 40% develop anxiety.1,11

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

An MS diagnosis is often determined using a system of symptom inclusion.5 Awareness of the differential diagnoses that mimic MS symptoms (eg, Lyme disease, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus, vasculitis, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematous, hereditary cerebellar degeneration, vitamin deficiencies, and structural damage to the CNS) may help expedite a diagnosis.5 If a patient presents with unresolved health issues, oral health professionals may want to encourage him or her to visit their primary care provider.12

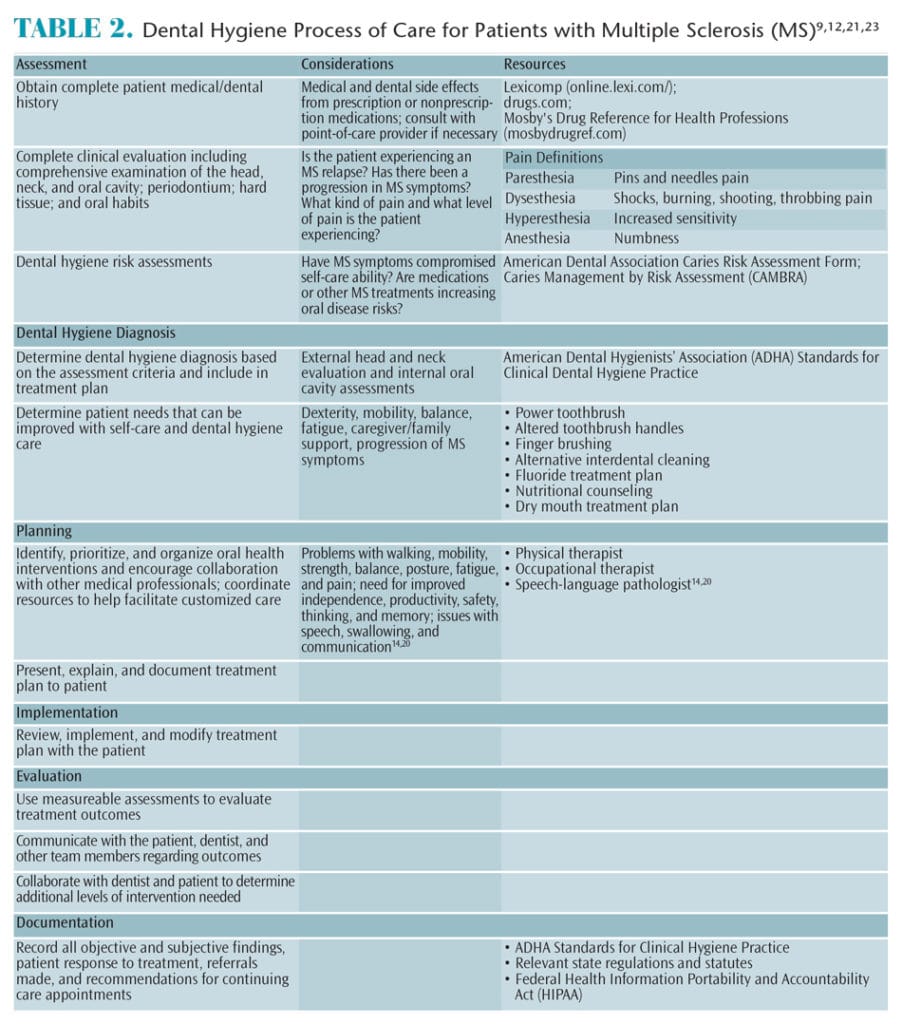

While there is no cure for MS, a variety of medications and alternative therapies can be used to help prevent future relapses and relieve symptoms.1–3,7,9,13 The primary treatment goal is to slow the disease process and reduce the number and frequency of relapses.9 Injectable, oral, and infused medications are used to treat MS (Table 1).9,13,14 Medication therapy at the onset of an MS diagnosis can help prevent cumulative and permanent nerve damage.3 Individuals who do not comply with treatment are more likely to experience MS relapse symptoms and incur higher medical expenses then those who follow treatment protocol.3

Many individuals with MS use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) to alleviate side effects.9 CAM therapies may include relaxation therapy, cognitive training, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, acupuncture, bowel cleansings, amalgam and root canal removal, and mineral supplements.9,15,16 While CAM therapies may provide some relief, scientific studies substantiating their efficacy are not available.9,15,16 CAM therapies that may reduce MS symptoms include the use of relaxation techniques to decrease anxiety and depression and cognitive rehabilitation programs to improve learning, memory, and activities of daily living.9,15,16 Oral health professionals should inquire whether patients are using CAM during the health history to ascertain any effects on oral health status and treatment planning.12

Drug research includes suppressing areas of the immune system that damage the CNS, while allowing other areas of the immune system to continue to operate normally.17 Research on the use of vitamin A to decrease inflammation and increase tolerance of autoimmunity is promising.18 Stem cell research is a complex process that has demonstrated a low risk/high reward treatment option, especially when used in conjunction with other disease-modifying agents.19 Additionally, remyelination drug therapies are being investigated to regenerate nerves damaged by MS.20,21

ORAL HEALTH RISKS

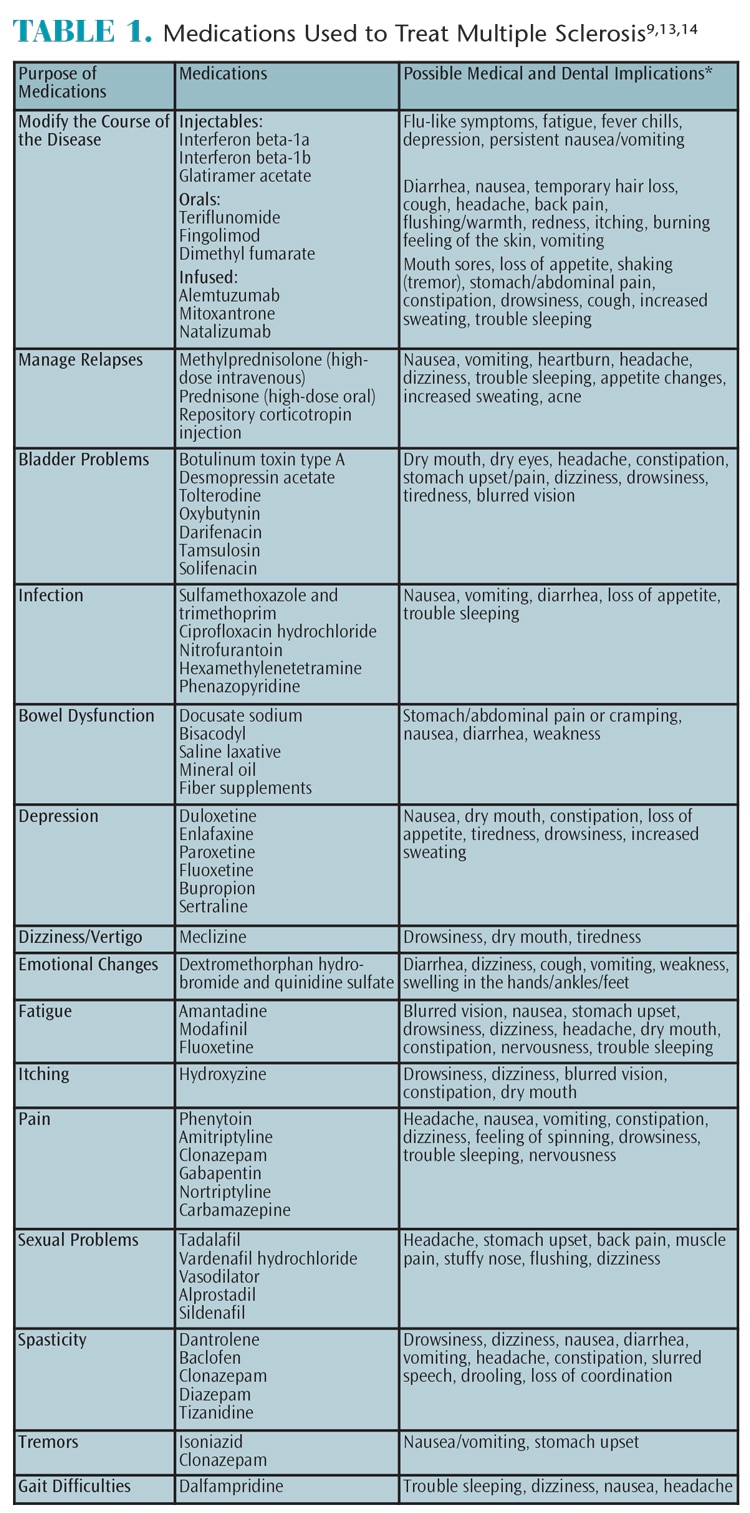

Individuals with MS are at increased risk for dental caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis due to the physical effects of MS, as well as reduced immune response.2,22 Specific and customized dental hygiene treatment planning and customized oral hygiene regimens need to be developed and implemented.2,12,22 Table 2 illustrates how to utilize the dental hygiene process of care when treating patients with MS.9,12,21,23

Systemic inflammation is a trigger for MS and chronic periodontitis contributes to inflammation.2,22 Basic periodontal treatment removing supra- and subgingival biofilm and calculus can reduce the inflammatory response in the entire body.2,22 Patients with MS tend to have more extensive gingival disease and increased numbers of decayed, missing, and filled teeth compared to those without MS.5,21

Physical disability is a barrier to performing adequate oral hygiene.2,5,21 Power toothbrushes or modified toothbrush handles are helpful with biofilm removal when manual dexterity is compromised.2 If dexterity, strength, and/or balance are concerns, a caregiver can provide physical support by holding onto the individual’s elbow or hand. If adequate oral hygiene is a concern, short but more frequent recare intervals at the dental office may help improve overall oral health.2

A caries risk assessment including defects of the hard tissue, existing restorations, fixed and removable appliances, fluoride exposure, xerostomia, diet, facial pain, and reduced dexterity can help determine a patient’s customized oral health treatment needs.2,12 In particular, nutritional counseling can help reduce caries risk.2,12 A patient with high caries risk should be placed on a fluoride treatment plan that includes at-home prescription fluoride products and in-office fluoride varnish applications.2,12

Common side effects of MS therapeutic medications are xerostomia, gingival hyperplasia, mucositis/ulcerative stomatitis, dysgeusia, candidiasis, angular cheilitis, and reactivation of herpes viruses.9,13 If patients are taking immunosuppressants, they may be at increased risk of opportunistic infections and cancers.23 Patients experiencing xerostomia need saliva substitutes and proper instruction on how to use them.9 Patients with candidiasis and/or angular cheilitis require anti-fungal medication, while those with herpetic lesions should receive anti-viral therapy.23 A complete list of a patient’s possible medical and oral health side effects will help determine which issues need to be addressed by the oral health professional.9 Obtaining a patient’s medical and prescription information prior to the appointment is helpful.9

Not only does smoking contribute to the worsening of MS symptoms, it encourages progression from RRMS to PPMS.8 When oral health professionals provide behavioral interventions for tobacco cessation, individuals may be more likely to quit tobacco use or avoid starting the use of tobacco products.24 Oral health professionals should be able to direct individuals to smoking cessation resources.

Many factors need to be considered when treating patients with MS. Short morning appointments are best when providing routine dental and dental hygiene care.2,23 Oral health professionals will need to alter treatment plans and procedures if the patient is experiencing pain, paralysis, spasticity, difficulty swallowing, and/or physical fatigue associated with MS.9 Most patients with MS can adequately state personal preferences for care and oral health values.11 Those with more advanced stages of disease might need a caretaker/guardian included in discussions about oral hygiene methods and the most comfortable treatment adaptations in the dental office. Oral health professionals need to listen attentively to the concerns expressed by the patient and/or caretaker in order for dental care to be successful.9

DENTAL OFFICE ADAPTATIONS

Individuals experiencing mild MS symptoms are more likely to continue regular oral health care visits than individuals with moderate to severe MS symptoms, especially if accessing care is difficult.21 Dental patients diagnosed with MS experience barriers to care such as difficulty accessing parking, the dental office building, waiting room, dental operatory, and restrooms.21 Oral health professionals can help patients with mobility issues stay safe and feel comfortable by keeping outdoor and indoor walkways clear of obstacles; noticing changes in the patient’s gait, mobility, and dexterity; choosing an easy access operatory; helping patients open building and restroom doors, if needed; scheduling follow-up appointments in the operatory instead of the reception counter; remaining flexible with appointment objectives, as all procedures may not be able to be completed in one visit; keeping up to date on medical transportation options; and initiating an open dialogue as to how future appointments can be improved.1,2,9,21 The entire dental team can contribute to the well-being of patients with MS as the disease symptoms change.

CONCLUSION

Patients with MS face many oral health risks—not only from loss of dexterity and side effects of medication usage, but also from cognitive, emotional, and social factors. Oral health professionals can create an environment that is conducive to patient needs and provide oral hygiene education that is appropriate for individual health concerns. By understanding the complexity and possible progression of MS symptoms, the dental team can facilitate an environment that encourages individuals with MS to seek appropriate oral health care for a lifetime.

REFERENCES

- Holland NJ, Schneider DM, Rapp R, Kalb RC. Meeting the needs of people with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, their families, and the health-care community. Int J MS Care. 2011;13:65–74.

- Elemek E, Almas K. Multiple sclerosis and oral health: An update. The Dental Assistant. 2014;83(5):32–39.

- Hanson KA, Agashivala N, Wyrwich KW, Raimundo K, Kim E, Brandes DW. Treatment selection and experience in multiple sclerosis: survey of neurologists. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:415.

- Kelly SB, Fogarty E, Duggan M, et al. Economic costs associated with an MS relapse. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:678–683.

- Toledano M, Weinshenker, BG, Solomon AJ. A clinical approach to the differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15:1–57.

- Hemmer B, Kerschensteiner M, Korn T. Role of the innate and adaptive immune responses in the course of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:406–419.

- Wekerle H. Nature plus nurture: the triggering of multiple sclerosis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;145:w14189–w14189.

- Briggs FB, Green MC, Ritterman Weintraub ML. Role of socioeconomic position in multiple sclerosis etiology. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2015;5:333–343.

- Simmer-Beck M. Providing Evidence-Based Oral Health Care to Individuals Diagnosed With Degenerative Disorders, Part 1: Multiple Sclerosis. Available at: dentalcare.com/en-us/professional-education/ce-courses/ce444/medications-to-modify-the-course-of-disease. Accessed November 28, 2016.

- Strober LB. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A look at the role of poor sleep. Front Neurol. 2015;6:1–7.

- Ghasemi M, Gorji Y, Ashtar F, Ghasemi M. A study of psychological well-being in people with multiple sclerosis and their primary caregivers. Adv Biomed Res. 2015;4:49.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2017.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Medications and Rehabilitation. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Available at: nationalmssociety.org/Treating-MS/Medications. Accessed November 28, 2016.

- WebMD. Drugs & Medications A–Z. Available at: webmd.com/drugs/index-drugs.aspx. Accessed November 28, 2016.

- Bogosian A, Chadwick P, Windgassen S, et al. Distress improves after mindfulness training for progressive MS: A pilot randomized trial. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1184–1194.

- Gich J, Freixanet J, García R, et al. A randomized, controlled, single-blind, 6-month pilot study to evaluate the efficacy of MS-Line!: A cognitive rehabilitation programme for patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1332–1343.

- Steinman L. The re-emergence of antigen-specific tolerance as a potential therapy for MS. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1223–1238.

- Fragoso Y, Stoney P, McCaffery P. The evidence for a beneficial role of vitamin A in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:291–299.

- Martinkaitytë P, Griðkevièiûtë R, Balnytë R. Stem cell therapy in multiple sclerosis: Current progress and future prospects. Neurologijos Sminarai. 2016;20(2):73–81.

- Kremer D, Küry P, Dutta R. Promoting remyelination in multiple sclerosis: Current drugs and future prospects. Mult Scler. 2015;21:541–549.

- Baird WO, McGrother C, Abrams KR, Dugmore C, Jackson RJ. Factors that influence the dental attendance pattern and maintenance of oral health for people with multiple sclerosis. Br Dent J. 2007;202:E4.

- Santa Eulalia-Troisfontaines E, Martínez-Pérez EM, Miegimolle-Herrero M, Planells-Del Pozo P. Oral health status of a population with multiple sclerosis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e223–e227.

- Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. Little and Falace’s Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 8th ed. 2013. St. Louis: Elsevier; 516–519.

- Carr A, Ebbert J. Interventions for tobacco cessation in the dental setting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;13:CD005084.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2016;14(12):44–47.