CREATAS IMAGES/CREATAS/THINKSTOCK

CREATAS IMAGES/CREATAS/THINKSTOCK

Improving the Oral Health of Older Adults

As the ranks of older adults continue to grow, oral health professionals must adapt their clinical approaches to meet the needs of this patient population.

This course was published in the December 2016 issue and expires December 31, 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the increasing number of older adults who present for dental care, and a proposed classification system that focuses on these patients’ functional abilities.

- Explain the factors that affect the oral and overall health of this patient population.

- List common types of visual impairment affecting older adults and appropriate adaptations in clinical approach to care.

- Recognize the signs of elder abuse, and know the reporting requirements when abuse is suspected.

The population of the United States is aging,1 and it will continue to do so as advances in medicine help Americans live longer.2 In 2014, life expectancy across the total US population was 76.4 years for men and 81.2 years for women.3 In light of this, oral health professionals are likely to treat older adults—defined as individuals age 65 or older1—with increasing regularity. Dental hygienists must be prepared to meet the needs of this aging population, and to make dental visits easier by recognizing the challenges they face.3

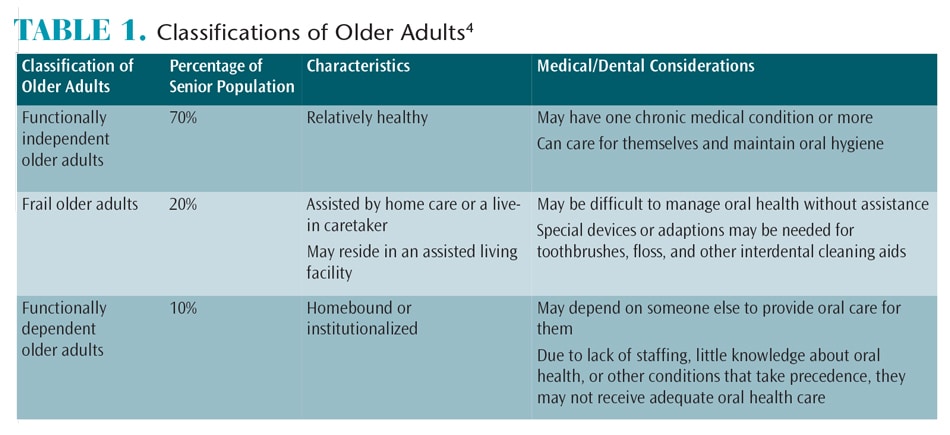

Ettinger and Beck4 suggested a classification of older adults that focused on the functional abilities of the aging population. It divided these individuals into three groups: functionally independent older adults, frail older adults, and functionally dependent older adults (Table 1). An individual’s health can quickly change due to events such as a stroke, heart attack, or fall. This may impact the individual’s dependency classification.

According to the 2010 US Census Report, there were 40.3 million Americans age 65 and older, up 3.5% from 2000.5 It is estimated that by 2030, 72 million Americans (or 19% of the US population) will be age 65 or older. And by 2050, it is projected that 89 million Americans will be 65 or older.6

There are two generations of older adults, and it is helpful to understand the major forces that shaped each generation. Individuals born between 1922 and 1945 are known as traditionalists, and are sometimes referred to as the silent generation. The oldest traditionalist is 94 and the youngest is 71. Traditionalist lived through or participated in World War II, or were children of World War II veterans. Older traditionalists remember the stock market crash of 1929 and lived through the Great Depression. As a result, traditionalists are likely to be thrifty, loyal, and hardworking, with respect for authority and traditions.7

When traditionalists’ lives began to return to normal following World War II, approximately 76 million US births occurred between 1946 and 1964. These individuals are known as the baby boomer generation. The US Census Bureau reported that in 2012 there were 65.2 million Americans in this category. The oldest baby boomer is 70 years old and the youngest is 52. In terms of the older adult population, boomers are turning 65 at a rate of approximately 8,000 per day. This generally is a hardworking and confident generation, characterized by individuals who are independent, self-reliant, competitive, and goal oriented.7

DENTAL CHALLENGES

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2006, approximately 25% of the US population age 60 and older were edentulous.8 It also notes that 23% of individuals between age 65 and 74 have severe periodontal diseases, and that older Americans may experience caries at rates that surpass those found in children.8 The CDC reports that oral and pharyngeal cancers—which are diagnosed in 31,000 Americans each year—result in 7,400 deaths each year, and that these cancers are primarily found in older adults.8 As such, older adults should be encouraged to maintain recare intervals that allow dental professionals to monitor oral health and screen for precancerous and cancerous lesions.

Many factors contribute to the oral health challenges faced by this patient population. Lack of adequate dental insurance, either public or private, is a major consideration for older adults, who may be on Medicare or have a fixed income. Medicare does not cover routine dental services (eg, prophylaxis, restorations, or dentures) unless additional coverage, such as Medicare Advantage, is purchased.9 Due to financial considerations, older adults may wait until they have a serious dental condition before seeking treatment. They may also elect less costly treatment than what is recommended.

In addition, disabilities, illnesses, and logistics may affect the decision to seek dental care. Older adults may have transportation issues, which can be especially problematic if multiple appointments are needed. A wide range of medications can affect oral health, and individuals within this patient population typically use multiple medications to treat chronic conditions. Many prescribed medications inhibit salivary flow and, as a side effect, may cause xerostomia—which, in turn, can contribute to the caries process. These individuals may also have medical or physical conditions that make it difficult to perform effective self-care. These challenges can contribute to decreased coping abilities during dental appointments.

ADAPTATIONS FOR TREATING OLDER ADULTS

Gerontology is defined as the treatment of dental problems specific to an advanced aging population.10 Many factors must be considered when treating older adults. Seventy million individuals age 55 or older have at least one chronic medical condition,11 and multimorbidity is common. According to a systematic review of the literature, the prevalence of multimorbidity in older adults ranges from 55% to 98%.12

The most common chronic conditions among this patient cohort are arthritis, hypertension, hearing loss, heart disease, and visual impairment.13 Other conditions that can affect these patients include limited manual dexterity, diminished peripheral circulation, loss of taste, and functional or organic mental disorders. Limited dexterity and diminished peripheral circulation can put patients at increased risk of caries and periodontal diseases due to difficulty with oral self-care. Devices, either homemade or commercially available, can assist patients by adapting the toothbrush or interdental cleaning aid so it is easier to use. As part of efforts to manage self-care, oral health professionals should be prepared to offer appropriate recommendations and encourage regular dental visits.

One in three Americans age 65 or older experiences hearing loss.14 When treating patients with hearing impairments, oral health professionals should eliminate background noises whenever possible. Clinicians are advised to face the individual and talk slowly and distinctly. Some patients may be able to hear, but have difficulty distinguishing sounds. Because consonants are more difficult to hear than vowels, choosing words carefully or using alternate expressions can be helpful. It may also be necessary to repeat questions or instructions. When appropriate—and if not providing treatment—oral health professionals may remove their masks so patients can see their lips as they talk. If the procedure requires the removal of hearing aids (such as when taking a panoramic radiograph), issue instructions to the patient before the hearing aids are removed.

If caregivers are present, oral health professionals should be sure to speak to the patient, not about the patient. That said, caregivers play a vital role, and—with the patient’s permission—it is often helpful to communicate directly about the patient’s dental care. Providing written communication regarding treatment and self-care can also help improve the oral health of older adults.

Multiple types of visual impairments can affect older adults, and it is important to understand these conditions and what can be done to help patients during a dental visit. Patients with glaucoma, for example, may have tunnel vision, so it is helpful for clinicians to remain in the patient’s central line of vision.

The opposite effect occurs with macular degeneration. Although these patients can see peripherally, they cannot see well in the center of vision. Magnifying glasses may be helpful if patients with macular degeneration must read material, such as consent forms, during the dental visit. When possible, keep the lights low in the treatment area. Clinicians are also advised to remain in patients’ peripheral vision area, and not in the central line of vision.

Another condition that can affect one or both eyes is hemianopia or hemianopsia. An individual with this condition has a lack of vision on one side. When addressing this patient, oral health professionals should stay out of the area that is blocked, and remain aware of obstacles in the patient’s way.15

Patients with cataracts see through a cloudy fog. It may be difficult for these individuals to read materials or walk through the office without help. In general, patients with vision impairments may have difficulty focusing on objects, adjust slowly to changes in lighting, and experience decreased depth perception. This can increase risks associated with navigating their surroundings, particularly in clinical environments.16

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

The loss of taste is another part of the aging process. A baby is born with 10,000 taste buds, but, by age 50, an adult will start losing taste buds. Contributing factors include medication usage, vitamin deficiencies, xerostomia, changes in salivary composition, diseases, and surgeries. Among older adults, the loss of taste can affect eating habits, potentially resulting in weight loss, poor nutrition, and vitamin deficiencies. It may be difficult for older adults to take medications.17

Mental disorders are categorized as functional or organic. A functional mental disorder has no physical cause. Depression, for example, can occur due to multiple factors, including the loss of family or loved ones. Older adults may lose their feeling of self-worth, or experience isolation from family and friends or relocation from their home. They may no longer feel as if they are contributing to society.

Delirium is another type of functional mental disorder. It is reversible and often caused by medications or alcohol use. Signs of delirium include an acute confused state. Organic mental disorders, including dementia, are irreversible. These conditions occur gradually and are caused by progressive deterioration of the brain cells. A variety of diseases can result in dementia, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and stroke.18

RECOGNIZING ELDER ABUSE

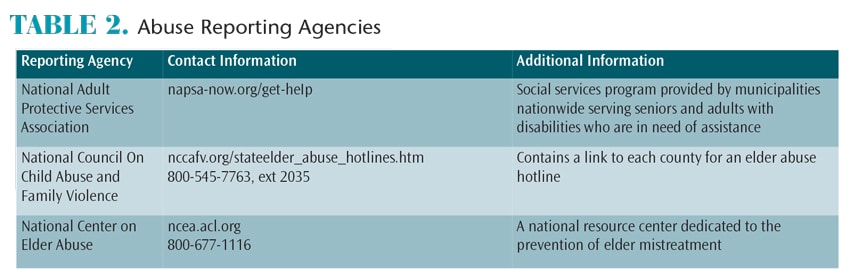

As health care providers, dental professionals must know the signs of elder abuse and how to report suspected cases (Table 2). Failure to report suspected abuse is a misdemeanor in most states. It is estimated that 5 million Americans age 65 or older have been injured, exploited, or mistreated by someone upon whom they depend for care and protection.19 Elder abuse can occur in lower, middle-, or upper-class households, and in rural, suburban, or urban areas. Defined as intentional withholding of care or services to someone who is dependent for care, neglect occurs in 58% of reported cases. Abuse includes touching or battery, but it can also involve a verbal element—which happens in 15% of reported cases.20

Although recognizing the signs and symptoms of elder abuse is important, clinicians should also realize that not every bruise or fracture is a sign of abuse. Oral health professionals should look for repeated or unexplained conditions. Bite marks, scars, lacerations and abrasions, fractured teeth, burns, bruises, poor personal hygiene, malnutrition, and signs of over- or under-medication could all be signs of abuse.

Clinicians should likewise be aware of caregiver stress that could potentially lead to an incident of elder abuse. Caregivers who are in distress may exhibit one or more symptoms, including denial about oral diseases and their effects on the person in their care. Such individuals may express anger at the person with the disease or illness, or show signs of anxiety, depression, exhaustion, irritability, or lack of concentration.

Dental teams should be prepared to share information about appropriate resources, including agencies and caregiver support groups at the local, state, and federal levels. The US Department of Health and Human Services’ Eldercare Locator (800-677-1116; eldercare.gov) and the American Association of Retired Persons’ Caregiving Support Line (877-333-5885; aarp.org) are two helpful contacts.

SUMMARY

Regardless of the patient’s circumstances, oral health professionals can assist older adults in achieving and maintaining oral health. For example, dental hygienists can recommend products and product modifications that can help patients perform effective self-care. Older adults should be encouraged to seek routine dental treatment and be educated about the risk of oral cancer and techniques for self-examination of oral tissue.

Dental teams should consult with patients’ physicians to coordinate care—a critical step in integrating oral care into overall health care, particularly for patients with comorbidities. When taking medical histories, include a complete list of prescriptions and over-the-counter medications being taken. Teams should also receive training in older adult care, including wheelchair transfers and compensating for vision or hearing impairments.

Due to physical and/or psychological conditions, older adults may have compromised coping skills, and additional care may be needed when communicating with patients. With consent, caregivers can be included in the discussions. Clinicians should avoid patronizing or stereotyping older adults, as most are competent to make health care decisions. Additionally, oral health professionals should be sensitive to transportation issues, scheduling constraints, and financial limitations that older adults might face.

Given the aging US population and advances in health care, an increasing number of older adults will present in the traditional dental practice. Regardless of age, the fundamentals of oral health care remain the same. Among this patient population, clinicians can increase the likelihood of successful outcomes by remaining sensitive to older adults’ health conditions, communicating clearly, and adapting techniques and procedures to accommodate their unique needs.

References

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. Available at: census.gov/content/dam/Census/ library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Mann D. Americans Living Longer, Healthier Lives. Available at: webmd.com/healthyaging/news/ 20111006/americans-living-longer-healthier-lives. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Arias E. Changes in Life Expectancy by Race and Hispanic Origin in the United States, 2013–2014. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/ db244.htm. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Ettinger RL, Beck JD. Geriatric dental curriculum and the needs of the elderly. Spec Care Dent. 1984;4:207–213.

- Branden E. 65-and-Older Population Soars. Available at: money.usnews.com/money/retirement/ articles/2012/01/09/65-and-older-population-soars. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Lukes S. Treating the geriatric dental patient. Available at: perioimplantadvisory.com/articles/ 2014/06/treating-the-geriatric-dental-patient.html. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- West Midland Family Center. Generational Differences Chart. Availabe at: wmfc.org/uploads/ GenerationalDifferencesChart.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health for Older Americans Fact Sheet. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/factsheets/adult_oral_health/adult_older.htm. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Your Medicare Coverage: Dental services. Available at: medicare.gov/coverage/dental-services.html. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- van der Putten GJ, de Baat C, De Visschere L, Schols J. Poor oral health, a potential new geriatric syndrome. Gerodontology. 2014;31(Suppl 1):17–24.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Percent of U.S. Adults 55 and Over With Chronic Conditions. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/ adult_chronic_conditions.htm. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Valachovic RW. Current Demographics and Future Trends of the Dentist Workforce. Available at: nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Workforce/oralhealthworkforce/2009-Feb-09/1%20-%20Valachovic.ashx. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- National Academy on an Aging Society. Chronic Conditions: A Challenge for the 21st Century. Available at: agingsociety.org/agingsociety/ pdf/chronic.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Hearing Loss Association of America. Basic Facts About Hearing Loss. Available at: hearingloss.org/ content/basic-facts-about-hearing-loss. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Hemianopsia.net. Hemianopsia (Hemianopia). Available at: hemianopsia.net. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Heiting G. How Your Vision Changes As You Age. Available at: allaboutvision.com/over60/vision-changes.htm. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Sollitto M. Loss of Taste in the Elderly. Available at: agingcare.com/Articles/Loss-of-Taste-in-the-Elderly-135240.htm. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Gagliardi JP. Differentiating among depression, delirium and dementia in elderly patients. Virtual Mentor. 2008;10:383–388.

- Rosen AL. Where mental health and elder abuse intersect. Generations. 2014;38:75–79.

- Watson E. Elder abuse: definition, types and statistics, and elder abuse (mistreatment and neglect) laws. J Legal Nurse Consult. 2013;24:40–42.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2016;14(12):48,51–53.