The Benefits of Breastfeeding

New evidence suggests that breastfeeding may have long term positive effects on children’s oral health.

This course was published in the September 2013 issue and expires September 2016. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the research on the association between breastfeeding and early childhood caries and orofacial growth and development.

- Identify the benefits of breastfeeding on systemic and oral health.

- Explain the suggested recommendations for breastfeeding mothers to support the oral health of their children.

On the other hand, few comprehensive studies have examined the oral implications of breastfeeding beyond an infant’s first 6 months of life. Some studies have suggested that prolonged breastfeeding may affect caries risk, quality of masticatory function, orofacial growth and development, and occlusion.3–9 Current research, however, has not demonstrated a significant association between breastfeeding and early childhood caries (ECC).4,10,11 Emerging evidence suggests that extended breastfeeding supports proper masticatory function and facial growth and development,3,7,9 and that poor oral hygiene, low socioeconomic status, and negative parental behaviors—rather than breastfeeding—may be greater risk factors for caries formation.4,5,12

In light of current information, oral health professionals should promote and support breastfeeding in concert with good oral hygiene practices. Additionally, with the increasing incidence of ECC among vulnerable populations in the United States (eg, those with complex medical problems, and/or social needs), rigorous inquiry into the effect of prolonged breastfeeding on caries risk is merited.4

EARLY CHILDHOOD CARIES

Caries, and the reduction of its incidence, is of great concern in pediatric dentistry. Infants who are exclusively breastfed are not immune to the threat of ECC, which in the past was thought only to affect bottle-fed infants and earned the moniker “baby bottle mouth.” The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry describes ECC as “the presence of one or more decayed, missing (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a child under the age of 6.”13

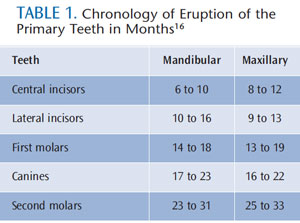

Severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) is a subcategory, distinguished from ECC by its progressive nature and acute symptoms. S-ECC is defined according to age: among children 3 years and younger, it is the presence of any smooth surface lesions; in children between the ages of 3 and 5, it is characterized by the presence of one or more maxillary anterior lesions, or a decayed/ missing/ filled teeth score of four, five, and six for ages 3, 4, and 5, respectively.14 Children with S-ECC are more likely to suffer an intense disease experience and are at greater risk for advanced disease progression.15 Because maxillary incisors are the first to erupt, they are the most susceptible to the cariogenic challenge and caries assault. If the challenge is discontinued and/or managed by proper self-care and fluoride, teeth that erupt later—such as primary canines, first molars, and primary second molars—may not be affected (Table 1).16

Clinically, early signs of ECC appear as a dull white, demineralized band of enamel that progresses to brown or black frank lesions along the gingival margin of the labial and lingual surfaces of primary maxillary incisors.17 Epidemiological evidence indicates that caries among preschool-age children occurs in both developed nations (12%) and underdeveloped nations (45% in Africa and Southeast Asia).18 Notably, the prevalence of ECC in children who are considered high risk within developed countries—specifically those belonging to ethnic minority groups and low-income families with poor parental attitudes and behaviors, such as smoking—is as high as 50% to 80%.17 Repercussions of ECC include increased risk for new caries lesions in both primary and permanent dentitions, frequent hospital and emergency department visits with exorbitant costs, loss of school days with impaired ability to learn, and delayed physical growth and development, as well as diminished quality of life.19

The correlation between breastfeeding and increased caries risk is subjective, with literature providing contrasting results. Literature reviews note a lack of consistency in methodology, clarity, and definitions, making it virtually impossible to compare practicality of multiple studies.4,5,10,20 Epidemiological overviews track breastfeeding habits and oral health indicators of the children in question, but often fail to address the complex and potentially confounding variables of fluoride exposure, presence of enamel hypoplasia, carbohydrate consumption, oral self-care routines, access to care, infrequent dental visits, socioeconomic factors, ethnicity, and environmental risk factors (smoking).4,5,10,20

Subjective, biased, and inconsistent reviews leave dental health professionals struggling to draw conclusions regarding recommendations to new mothers. In the absence of strong evidence, professionals fall back on traditional recommendations based on tooth eruption patterns. For example, the presence of new teeth and the perceived increase in risk for ECC may lead dental professionals to recommend infants be weaned from breast milk at 6 months.4 And, although the rationale and evidence for doing so are unclear, the current American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry policy statement on ECC recommends that “ad libitum breastfeeding should be avoided after the first primary tooth begins to erupt and other dietary carbohydrates are introduced.”13 Ribeiro and Ribeiro questioned whether the decision to avoid spontaneous breastfeeding is based on combining on-demand and nighttime breastfeeding into one category, as their issues may differ.20 Additionally, the authors state the biomechanics of breastfeeding are such that breast milk is directed into the soft palate and swallowed, avoiding contact with teeth for protracted periods.20 This policy to restrict breastfeeding conflicts with the WHO 2013 and the American Academy of Pediatrics 2005 and 2012 breastfeeding recommendations.1,2

Furthermore, because breast milk production is proportional to infant demand, restrictions may decrease supply and disrupt feeding patterns. In its revised policy, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry “encourages breastfeeding of infants to ensure the best possible health and developmental and psychosocial outcomes, with care to wiping or brushing as the first primary tooth begins to erupt and other dietary carbohydrates are introduced.”21 In vitro studies22,23 indicate that compounds found in breast milk may have the ability to inhibit the adhesion and proliferation of Streptococci mutans on tooth surfaces, although there is no epidemiological evidence to suggest breastfeeding reduces the risk for caries in infants.5 In its support of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations for breastfeeding, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry cautions that “the potential for [ECC] is related to extended and repetitive feeding times, with prolonged exposure of teeth to fermentable carbohydrates without appropriate oral hygiene measures.”24 It recommends that nighttime feedings be replaced with tap water,23 providing the additional benefit of fluoride protection to developing teeth in communities with fluoridated water. Careful consideration must be exercised in regard to a child’s general health when determining omission of breast milk for water. Such decisions should be made only after consultation with the child’s pediatrician. Any decrease in feeding patterns potentially impacts yield, and may affect the nutritional requirements of the young child.

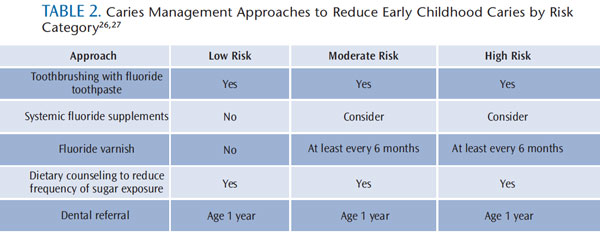

Comparative studies between breast milk and milk-alternatives indicate the amount of fluoride passed from mother to infant via breast milk is negligible,25 therefore, fluoride is one of a number of hygiene changes that should be considered with the arrival of teeth. Mothers may not be making significant enough adjustments as their infants’ teeth begin to erupt. Oral health professionals should emphasize that eruption of teeth in infants marks the beginning of routine dental check-ups and implementation of a caries management protocol according to risk (Table 2).26,27

OROFACIAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

OROFACIAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Though caries risk is the foremost concern in pediatric dentistry, this stage of growth could set the trajectory for other vital developments.

Although genetics plays a role in occlusion, negative lifestyle factors can cancel out positive genealogical traits.6 There appears to be a positive correlation between early cessation of breastfeeding and Class II malocclusions.7 This indicates breastfeeding may be viewed as a positive influence in preventing dental malpositioning. Much of the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding can be viewed as a lesser benefit of one behavior than an absence of exposure to harmful alternatives. One study suggests that infants weaned from breast milk before 6 months of age are four times more likely to develop other sucking habits.6

The breast itself is soft and easily adapts to the shape of an infant’s mouth; bottles and pacifiers have a less yielding structure, and force the infant’s mouth to change around them.3 Bottle feeding uses a different sucking action, which requires the tongue to move in a piston-like manner, pressing the artificial nipple against the hard palate. This frequently results in a tongue-thrusting motion that may cause further damage to occlusion in the future.3 Weaning prior to 6 months often signals the beginning of other oral habits that serve no nutritive or developmental purpose, but force oral structures out of alignment. Research on nonnutritive sucking habits suggests the resultant pacifier and finger-sucking habits may be responsible for skeletal changes that narrow the maxillary palate.8 Malocclusions that may result include posterior crossbite, anterior open bite, and excessive overjet, in addition to Class II malocclusions. The long-term effects of these malocclusions can lead to esthetic problems and difficulty chewing, speaking, and swallowing.8

Breastfeeding also has long-term effects on craniofacial development. The jaw movement associated with feeding from the breast stimulates growth of the temporomandibular joint, as well as the maxilla and mandible. According to Viggiano et al,28 breastfeeding “draws milk, pulling both the nipple and the areola into the mouth; the movement of the lips and tongue contribute more to squeezing than to sucking.” During breastfeeding, the tongue moves in a peristaltic-like motion, creating functional stimulus to the jaw and associated facial structures that is conducive to normal development.28 Sucking associated with bottle and pacifier use results in a different functional stimulus, which may damage the process of facial development.9

Breastfeeding plays an important role in the development of facial structures, muscles, and habits, and it may be linked to a lower incidence of developmental disorders. Additionally, healthy breastfed children are at a reduced risk for obstructive sleep apnea and sudden infant death syndrome because of the immunological and anti-inflammatory qualities of breast milk.3,11

MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH BENEFITS

Breastfeeding provides short- and long-term health benefits, and simultaneously reduces health risks in mothers who breastfeed.29 Breastfeeding may prevent language and motor skill development delays.30 Additionally, milk contains bioactive substances—including hormones, growth factors, immunological factors (IgA and IgG) and anti-inflammatory properties31—that reduce the risk for health problems, such as acute otitis media, gastroenteritis and diarrhea, leukemia-related viruses, asthma, obesity, and type 2 diabetes.29 In terms of benefits to mothers, breastfeeding may protect against breast and ovarian cancers through reduction of certain hormone levels, and suppression or delay of ovulation.32

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

WHO advises mothers to exclusively breastfeed during the first 6 months of an infant’s life, and recommends the continuation of breastfeeding, in addition to other suitable sources of nutrition, for up to 2 years or beyond.2 And, given the preponderance of evidence regarding its benefits and the lack of consistent research linking breastfeeding to the development of ECC, dental professionals should support current recommendations for breastfeeding.4 There is no right time to stop breastfeeding, and mothers should be encouraged to continue as long as they wish.10 When making the decision to wean an infant, each situation must be assessed carefully, and according to the child’s individual needs.

The first dental visit should occur within 6 months of eruption of the first tooth and no later than 12 months of age. Also, because decreasing the levels of cariogenic bacteria (especially S. mutans) reduces caries risk and improves oral health, counseling should begin with expectant parents to determine oral health status and limit bacterial transmission.33 Oral health professionals should emphasize good oral hygiene practices for the entire family, as well as the newborn.

After breastfeeding and once the first tooth has emerged (and when additional dietary carbohydrates are offered), the tooth should be wiped and brushed with a clean washcloth or a child’s soft toothbrush. An infant finger toothbrush may be used in place of a traditional toothbrush (Figure 1). When supplementing breastfeeding with food, caregivers need to reduce the frequency and consumption of sugar-dense foods and drinks. Also, some over-the-counter and prescription medications contain sugar and acidic preparations that put patients at risk for caries and dental erosion—particularly when used frequently and during bedtime.34 Parents and caregivers should be educated regarding the importance of caring for infant teeth, which includes wiping teeth and gingiva after breastfeeding or eating/ drinking. Parents should consider asking a pediatric specialist for sugar-free alternatives to medication (if available), and dental professionals should campaign for and promote increased availability of sugar-free pediatric medications from pharmaceutical companies.

With the appearance of the first tooth, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry recommends that the parent/ caregiver brush the child’s tooth/ teeth twice daily. For children up to age 2, a smear (0.1 mg) of fluoride toothpaste is recommended; for children age 2 and older, brushing twice daily with a pea-size amount of fluoride toothpaste (0.2 mg) is sufficient.35 Oral health professionals also need to advise breastfeeding mothers that if a fluoride supplement is indicated, it should be administered 30 minutes prior to or after ingestion of breast milk, as its absorption and effectiveness can be reduced by the calcium in milk.

Finally, oral health professionals may want to consider creating a written breastfeeding policy that is regularly communicated to staff members. Keep in mind that all infants, regardless of how they are fed, require scrupulous monitoring of growth and illness, with appropriate interventions undertaken when clinically indicated.

CONCLUSION

Breastfeeding offers widespread systemic benefits, making it impractical to recommend its reduction for the purpose of caries prevention, as has been suggested in the past. Evidence demonstrates that in the absence of other harmful factors, such as potential disease transmission from mother to child or transmissible environmental pollutants, breastfeeding has positive effects that go beyond immunological and nutritive benefits. Based on the role that proper feeding techniques play in ideal development of the occlusion, masticatory function, and bone and muscle development of the face, breastfeeding should be encouraged as long as it remains desirable for both mother and child.

In 2011, the US Surgeon General released a call to action for health care providers to be educated and trained about the importance of breastfeeding, and to provide patients with evidence-based information in its support.36 Although more research is needed to demonstrate associations between breastfeeding and ECC—in particular within vulnerable populations—efforts should be made to pair breastfeeding with optimal oral health maintenance practices to promote proper orofacial and occlusal development, and to prevent the formation of ECC. The implementation of effective and consistent breastfeeding policies based on scientifically sound studies is recommended.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Pediatrics. AAPReaffirms Breastfeeding Guidelines. Available at: www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-pressroom/pages/AAP-Reaffirms-Breastfeeding-Guidelines.aspx. Accessed August 20, 2013.

- World Health Organization. Ten facts on breastfeeding. Available at: www.who.int/features/factfiles/breastfeeding/en. Accessed August 20, 2013.

- Agarwal M, Ghousia S, Konde S, Raj S.Breastfeeding: nature’s safety net. InternationalJournal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2012;5(1):49?53.

- White V. Breastfeeding and the risk of early childhood caries. Evid Based Dent.2008;9:86?88.

- Kramer MS, Vanilovich I, Matush L, et al. The effect of prolonged and exclusive breast-feeding on dental caries in early school-age children.New evidence from a large randomized trial. Caries Res. 2007;41:484?488.

- Luz C, Garib D, Arouca R. Association between breastfeeding duration and mandibular retrusion: a cross-sectional study of children inthe mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:531?534.

- Nowak AJ, Warren JJ. Infant oral health and oral habits. Pediatr Clin North Am.2000;47:1043?1066.

- New Malocclusion Study Results Reported from Federal University. Available at: www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-290907758.html.Accessed August 20, 2013.

- Pires, S, Giugliani, E, Caramez da Silva, F.Influence of the duration of breastfeeding on quality of muscle function during mastication in preschoolers: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:934.

- Valaitis R, Hesch R, Passarelli C, Sheehan D,Sinton J. A systematic review of the relationship between breastfeeding and early childhoodcaries. Can J Public Health. 2000;91:411?417.

- Hauck FR, Thompson JM, Tanabe KO, MoonRY, Vennemann MM. Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta analysis.Pediatrics. 2011;128:103?110.

- Lida H, Auinger P, Billings RJ, Weitzman M.Association between infant breastfeeding and early childhood caries in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120:944?952.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry,American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy of early childhood caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatr Dent. 2008;34:50?52.

- Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, Maertens MP, Rozier RG, Selwitz RH. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. A report of a workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Health Care FinancingAdministration. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:192?197.

- Powell LV. Caries prediction: a review of thel iterature. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol.1998;26:361–371.

- Tooth eruption, the primary teeth. J Am DentAssoc. 2005;11:1619.

- Berkowitz RJ. Causes, treatment, and prevention of early childhood caries: a microbiologic perspective. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:304?307.

- Vadiakas G. Case definition, a etiology and risk assessment of early childhood caries (ECC): are visited review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9:114?125.

- Colak H, Dulgergil CT, Dalli M, Hamidi MM.Early childhood caries update: A review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013;4:29?38.

- Ribeiro NM, Ribeiro MA. Breastfeeding and early childhood caries: a critical review. J Pediatr(Rio J). 2004;80(Suppl 5):S199?S210.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.Policy on dietary recommendations for infants,children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:54?58.

- Danielsson Niemi L, Hernell O, Johansson I.Human milk compounds inhibiting adhesion of mutans streptococci to host ligand-coatedhydroxyapatite in vitro. Caries Res. 2009;43:171?178.

- Holgerson P, Vestman NR, Claesson R, et al.Oral microbial profile discriminates breast-fed from formula-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:127?136.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.Policy on breastfeeding. Pediatr Dent.2003;25:111.

- Koparal, E, Ertugrul, F, Oztekin, K. Fluoride levels in breast milk and infant foods. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2000;24:299?302.

- Brown A, Lowe E, Zimmerman B, Crall J,Foley M, Nehring M. Preventing early childhood caries: lessons from the field. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:553–560.

- Vogel S. General anesthesia in the treatmentof early childhood caries. Dimensions of DentalHygiene. 2012;10(10):19–22.

- Viggiano D, Fasano D, Moncaco G,Strohmenger L. Breastfeeding, bottle feeding,and non-nutritive sucking; effects on occlusion indeciduous dentition. Arch Dis Child. 2004; 89: 1121?1123.

- Salone LR, Vann WF, Dee DL. Breastfeeding:an overview of oral and general health benefits.J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:143?151.

- Dee DL, Li R, Lee LC, Grummer-Strawn LM.Associations between breastfeeding practices and young children’s language and motor skill development. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 1): S92?S98.

- Garofalo R. Cytokines in human milk.J Pediatr. 2010;156(Suppl 2):S36–S40.

- Stuebe A. The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Rev Obstet Gynecol.2009;2:222?231.

- Kishi M, Abe A, Kishi K, Ohara-Nemoto Y,Kimura S, Yonemitsu M. Relationship of quantitative salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and S. sobrinus in mothers to caries status and colonization of mutans streptococci in plaque in their 2.5-year-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:241?249.

- Neves BG, Pierro VS, Maia LC. Pediatricians’ perceptions of the use of sweetened medications related to oral health. J Clin PediatrDent. 2008;32:133?137.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.Frequently Asked Questions, Toothpaste: when should we begin using it and how much should we use? Available at: www.aapd.org/ resources/frequently_asked_questions/. Accessed August 20, 2013.

- US Department of Health and HumanServices. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action toSupport Breastfeeding. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/ library/ calls/ breastfeeding/calltoactiontosupportbreastfeeding.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2013.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2013; 11(9): 46–50