Successful Management of Adult Patients With Cerebral Palsy

Personalized education and treatment are critical to effective dental hygiene care.

This course was published in the April 2020 issue and expires April 2023. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define cerebral palsy (CP) and its four main classifications.

- Identify oral health risks related to CP.

- Role of medication regimens on the oral health of individuals with CP.

- Identify strategies to ensure successful provision of dental hygiene care for adults with CP.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a disorder caused by encephalic damage that occurs during fetal development or infancy; it impairs motor coordination, cognitive function, sensation, perception, and communication abilities. A lifelong disability, CP increases the risk for oral health disparities and comorbidities in adulthood. The disabilities presented by CP are not progressive, but they are permanent, and they impact health and well-being. As treatment has improved, life expectancies of those with CP have continued to grow, which has increased the demand for inclusive oral-systemic healthcare to enhance quality of life.1–10

CLASSIFICATIONS OF CEREBRAL PALSY

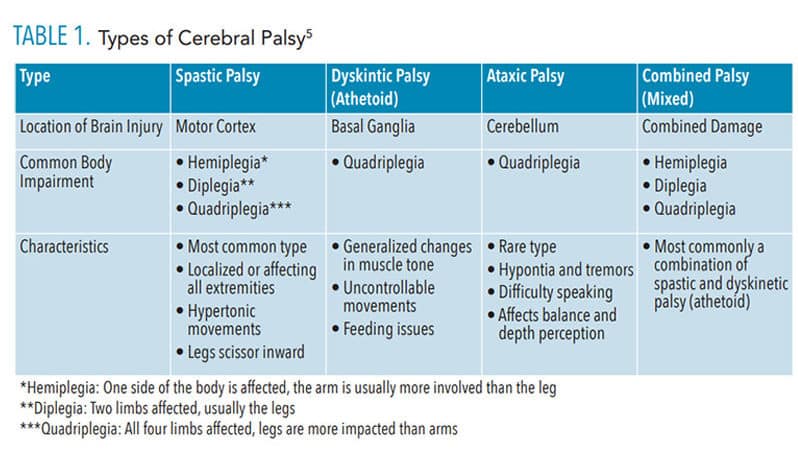

There are four main classifications of CP: spastic, dyskinetic (athetoid), ataxic, and mixed (Table 1). Spastic palsy is the most prevalent (80% to 95%) and causes stiff, rigid muscles; affects the limbs unilaterally or bilaterally; and often leads to the appearance of legs that “scissor” inward. Dyskinetic (athetoid) palsy impacts approximately 7% of those with CP and is identified by uncontrolled or involuntary movements, muscle tone abnormalities, hypokinesia, and/or hypertonia. Of adults with CP, 4% have ataxic palsy, which results in distortion of balance and depth perception, generalized hypotonia with abnormal force, and/or inaccuracy of movement. A combination of impairments and brain damage leads to mixed palsy with spasticity and dyskinesia as the most common impairments. Individuals with mixed palsy may exhibit a range of the above symptoms. Oral health professionals with knowledge of the CP classifications will be best prepared to provide the most effective and safe care.1,2,5

The severity of the peripartum brain injury determines the damage to functional abilities and is described by the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) I-V for children and young adults.1,2,4,11 The system rates these impairments as follows:4,11

- Walks without restrictions; limitations for running and jumping

- Walks with assistance from small appliances and/or crutches; slight community ambulation limitations

III. Walks with the assistance of walker and/or crutches; community ambulation difficulties

- Walks with the assistance of walker but with limitations; requires a wheelchair for community ambulation

- Severely limited mobility, even with appliances and adaptations; wheelchair adaptations required

As CP is a life-long disability, any limitations to motor function will remain into adulthood. Dental hygienists may use their knowledge of GMFCS to identify risks of chronic diseases. The system may also help dental hygienists to develop clinical interventions and patient education customized to individual patients.

CARIES, PERIODONTAL DISEASES, AND BRUXISM

Dental hygiene assessment of risk factors impacting oral health is imperative for prevention and management of oral diseases among adults with CP. This patient population is at elevated risk for caries and periodontal diseases due to difficulty with biofilm control, loss of motor function, and decreased access to oral healthcare. The combination of high biofilm indices, mouth breathing, and infrequent dental visits are contributing factors for both diseases.4,12–14

Studies show that caries risk is elevated among children with CP, but the literature is deficient regarding caries prevalence for adults with CP.13,15,16 Al-Allaq et al15 reviewed the 2008-2009 dental records of 478 adults with CP. While not statistically significant, the authors found that caries risk increased along with the age of individuals with CP, and that oral motor function impairments and difficulty with oral hygiene execution enhanced caries risk. In 2014, Santos et al13 studied 65 individuals with CP from ages 6 to 13 and found the subjects’ level of motor skills and ability to clear food from the oral cavity impacted caries risk and severity.

Considering motor function impairments are lifelong among those with CP, a caries prevention plan is imperative for this population. Providing customized recommendations for oral self-care products and aids to patients and caregivers is critical to caries prevention. Additionally, a tailored schedule for fluoride therapy should be provided based on individual risk factors and disease progression.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is common among those with CP, and it increases the risk of erosion and caries.4,5,13,16 Dental hygienists may want to consider prescription and/or dentist-dispensed antimicrobial products to combat these risks. Silver diamine fluoride may also help arrest caries or prevent the progression of carious lesions found in adults with CP.17

The severity of periodontitis has also been associated with the degree of rigidity and muscle tone among those with CP, as it impacts the ability to perform self-care.18 Many of these patients rely on others to help them with activities of daily living, including oral self-care, which can inhibit the success of an oral hygiene regimen. Minihan et al19 surveyed 808 caregivers of individuals with development disabilities of which 125 were caregivers of adults with CP. Many reported that physical difficulties were a significant barrier to providing oral self-care. Caregivers were also less likely to recognize the symptoms of periodontal diseases, which inhibited the likelihood that individuals with CP received professional oral healthcare.

The oropharyngeal muscles common among those with CP impact nutrition and diet.20 Oral motor disorders affect swallowing and contribute to feeding difficulties.6,21 As a result, undernutrition is a concern and vitamin C deficiency is common, which can raise the risk of periodontal diseases.20,22 Periodontal risk assessment is important to prevent disease progression. Identifying reasonable self-care regimens, shortened recare intervals, adjunctive chemotherapeutic agents, and dietary counseling should be part of the dental hygiene care plan for this patient population.

Bruxism is also common among adults with CP. The onset of bruxism is associated with malocclusion and behavioral and genetic patterns. Other contributing factors are decreased muscle tone (hypotonia) of oral structures with consequent tongue thrusting and mouth breathing. In addition, cognitive and motor impairments increase the severity of bruxism’s impact on oral structures.6,21 In 2009, Dougherty14 published a review that cited higher rates of dental trauma associated with malocclusion, specifically angle class II with an anterior open bite, in individuals with CP. Rodriguez et al16 found that 21% of 120 individuals with CP had experienced dental trauma. Results also showed that the prevalence of dental injuries seemed to increase with higher rates of malocclusion.

Uncontrollable head movements and epileptic seizures are often responsible for dental injuries among individuals with CP.16,23 During dental hygiene care, conducting a thorough hard tissue assessment with intraoral photography may be helpful in monitoring changes. Subsequent treatment for bruxism may be indicated based on clinical manifestations and observed changes.

ROLE OF MEDICATION REGIMENS

Medications taken by adults with CP may also impact oral health. Five main drug classes are commonly prescribed to control CP symptoms:24,25

- Anticholinergics to control muscle spasms, sialorrhea, and urinary incontinence

- Anticonvulsants for epileptic episodes

- Antidepressants for depression; antispastic/muscle relaxant for muscle spasms

- Anti-inflammatory medication for pain

These medications are often used in combination to treat multiple symptoms simultaneously. Common side effects include xerostomia, gingival hyperplasia, and increased risk of bruxism.25–27

Anticonvulsants commonly prescribed to manage seizures may cause gingival hyperplasia and xerostomia, which raises caries risk.12,26 Gingival hyperplasia can cause damage to the periodontium’s lymphatic and vessel system, which may increase the likelihood of periodontal diseases.

Adults with CP may take anticholinergics to reduce sialorrhea (drooling).21 These drugs may cause side effects such as xerostomia, constipation, and urinary incontinence.26 Xerostomia increases biofilm accumulation and food retention and raises the risk for caries and periodontal inflammation. An alternative treatment for sialorrhea is injection of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) into the salivary glands, which has provided positive results with fewer side effects.21 Oral health professionals should understand the impact of medication regimens for CP on oral health so they can help their patients ameliorate those risks.

INCREASING THE SUCCESS OF DENTAL APPOINTMENTS

To effectively care for adults with CP, dental hygienists should be prepared to collaborate with other healthcare providers, caregivers/family members, and social workers. In addition, dental hygienists should support autonomy of adults with CP to make their own oral healthcare decisions.10

Determining what type of modifications may be needed to increase the success of the dental appointment is a prudent strategy. Inquiring about what time of day and how long the patient can remain in the dental chair should inform appointment scheduling. Depending on the level of motor function and potential cognitive impairment, scheduling short morning appointments at the beginning of the week may be beneficial to ensure the individual is best able to tolerate the appointment.1

The dental chair may need to be adjusted so that it is more upright, and pillows should be provided to add support behind the neck to enhance patient comfort. The upright positioning of the dental chair may result in dental hygienists performing “standing” hygiene. Additionally, a wheelchair transfer or wheelchair-based care may be needed. Contacting the patient or caregiver in advance to determine necessary modifications may be helpful. Dental hygienists should inquire about the extent and frequency of the patient’s involuntary movements to provide a safe environment as well.5 Adults with CP may require protective stabilization equipment, such as velcro straps, to prevent involuntary movements, specifically with arms.

Dental hygienists may also need to modify the dental hygiene appointment and patient education to the patient’s level depending on GMFCS scores. Adults with CP may have sensory issues related to textures, scents, and sounds.1,2 This may make the use of ultrasonic scalers and slow-speed handpieces and implementation of polishing and fluoride agents challenging. In addition, oral health professionals will need to consider the cognitive, sensory, and functional status of patients when recommending a self-care regimen. A thorough interview with the patient and caregiver before delivering dental hygiene care or developing a self-care regimen may increase the success of the dental appointment and improve patient compliance.

CONCLUSION

Adults with CP are at greater risk for oral health problems, and dental hygienists are well-positioned to provide effective care as well as effectively educate patients and their caregivers and suggest appropriate self-care regimens.

REFERENCES

- Bax M, Goldstein M, Rosenbaum P, et al. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:571–600.

- Wimalasundera N, Stevenson VL. Cerebral palsy. Pract Neurol. 2016;16:184–194.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data and Statistics for Cerebral Palsy. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/cp/data.html. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Park EY, Kim WH. Prevalence of secondary impairments of adults with cerebral palsy according to gross motor function classification system. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29:266–269.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Practical Oral Care for People With Cerebral Palsy. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-09/practical-oral-care-cerebral-palsy.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Yogi H, Alves LAC, Guedes R, Ciamponi AL. Determinant factors of malocclusion in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;154:405–411.

- Healthy People 2020. Disabilities and Health. Available at: healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/disability-and-health. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General executive summary. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2000;28:685–695.

- World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF—the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Available at: who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Orlin MN, Cicirello NA, O’Donnell AE, Doty AK. The continuum of care for individuals with lifelong disabilities: role of the physical therapist. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1043–1053.

- Palisano RJ, Copeland WP, Galuppi BE. Performance of physical activities by adolescents with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. 2007;87:77–87.

- Sun D, Wang Q, Hou M, et al. Clinical characteristics and functional status of children with different subtypes of dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(21):e10817.

- Santos MT, Biancardi M, Guare RO, Jardim JR. Caries prevalence in patients with cerebral palsy and the burden of caring for them. Spec Care Dentist. 2010;30:206–210.

- Dougherty NJ. A review of cerebral palsy for the oral health professional. Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53:329–338.

- Al-Allaq T, DeBord T, Liu H, Wang Y, Messadi DV. Oral health status of individuals with cerebral palsy at a nationally recognized rehabilitation center. Spec Care Dentist. 2015;35:15–21.

- Rodríguez JPL, Ayala-Herrera JL, Muñoz-Gomez N, et al. Dental decay and oral findings in children and adolescents affected by different types of cerebral palsy: a comparative study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2018;42:62–66.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Use of silver diamine fluoride for dental caries management in children and adolescents, including those with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39:146–155.

- Ryan JM, Allen E, Gormley J, Hurvitz EA, Peterson MD. The risk, burden, and management of non-communicable diseases in cerebral palsy: a scoping review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60:753–764.

- Minihan PM, Morgan JP, Park A, et al, Must A. At-home oral care for adults with developmental disabilities: a survey of caregivers. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:1018–1025.

- Ziegler J, Spivack E. Nutritional and dental issues in patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149:317–321.

- Botti Rodrigues Santos MT, Duarte Ferreira MC, de Oliveira Guaré R, Guimarães AS, Lira Ortega A. Teeth grinding, oral motor performance and maximal bite force in cerebral palsy children. Spec Care Dentist. 2015;35:170–174.

- Tada A, Miura H. The relationship between vitamin C and periodontal diseases: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2472.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Drug treatments. Available at: ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Hope-Through-Research/Cerebral-Palsy-Hope-Through-Research#3104_17. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Colver A, Fairhurst C, Pharoah PO. Cerebral palsy. Lancet. 2014;383:1240–1249.

- Wolff A, Joshi RK, Ekström J, et al. A guide to medications inducing salivary gland dysfunction, xerostomia, and subjective sialorrhea: a systematic review sponsored by the World Workshop on Oral Medicine VI. Drugs R D. 2017;17:1–28.

- Papadakou P, Bletsa A, Yassin MA, Karlsen TV, Wiig H, Berggreen E. Role of hyperplasia of gingival lymphatics in periodontal inflammation. J Dent Res. 2017;96:467–476.

- Chowdhury N, Sewatsky M, Kim H. Transdermal scopolamine withdrawal syndrome case report in the pediatric cerebral palsy population. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:e151–e54.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2020;18(4):38-41.