BYMURATDENIZ/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

BYMURATDENIZ/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Impact of Diet on Oral Health

Providing nutritional counseling is an important part of dental hygiene care to improve both oral and systemic health.

This course was published in the April 2020 issue and expires April 2023. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the role nutrition plays in oral health.

- Identify popular diet trends and their impact on oral and systemic health.

- Explain how to provide a nutritional assessment and nutritional counseling.

As healthcare providers, dental hygienists help improve patients’ oral and systemic health through education. Medical history review, oral examination, and a nutritional assessment enable dental hygienists to identify behaviors or components of a patient’s diet that cause or contribute to oral disease. Taking a nutritional history is an important part of the dental hygiene process of care, as it allows oral healthcare providers to assess an individual’s risk for potential nutritional deficiencies based on dietary choices.1 Patient education should focus on the treatment and/or prevention of disease through oral hygiene practices and diet and nutritional counseling.

The United States Department of Agriculture and the US Department of Health and Human Services update the Dietary Guidelines for Americans every 5 years. The guidelines recognize there are many factors that influence individuals’ dietary choices. However, the most profound impact comes from the settings in which individuals live, learn, work, and play.2 This means patients may be getting their nutritional advice from the people around them and not necessarily from reliable sources. Oral health professionals are well-suited to identify, educate, and address nutritional issues as they relate to the oral cavity.

IMPACT OF NUTRITION ON ORAL HEALTH

The relationship between diet and caries is well documented, yet, the consumption of fermentable carbohydrates remains a significant factor in caries development.3 Disaccharides (sucrose) are carbohydrates found in foods such as candy, sweets, and soda. For many years, sucrose was thought to be the most cariogenic substance; however, current research shows that polysaccharides (starch), when combined with sucrose and monosaccharides (simple sugars such as glucose), are equally detrimental to tooth structures.4 Reducing or eliminating these types of foods is ideal especially for high-risk patients. Encouraging patients to make changes, such as rinsing with water after the consumption of a carbohydrate-containing food, chewing xylitol-containing gum, and maintaining good oral hygiene practices will help offset the impact of fermentable carbohydrates on tooth structures.5

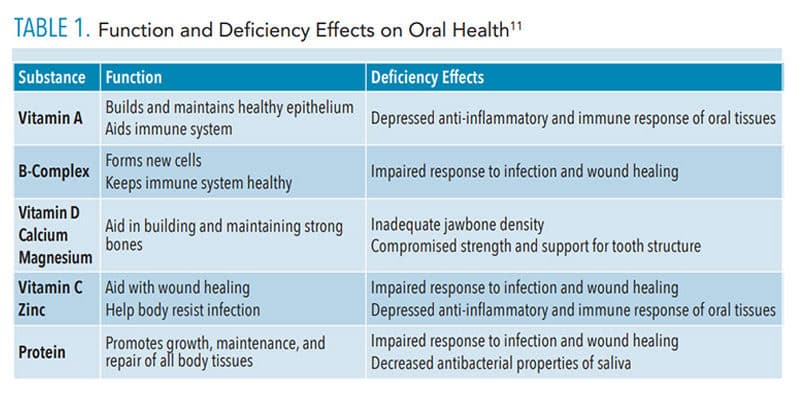

Periodontitis is a bacterial disease characterized by bleeding, inflammation, and loss of bone and supporting structures.6 The prevention, treatment and management of any disease, including periodontal inflammation, relies on the normal function of the immune system, which is supported by proper nutrition.7 While chronic deficiencies are more apparent, subtle, acute deficiencies are difficult to detect and their impact on the periodontium is less obvious. As the oral mucosa is often the first tissue to show signs of nutrient deficiencies or excesses, dental hygienists must be aware of the role nutrition plays in oral health.

POPULAR DIET TRENDS

With more than 70 million Americans in the obese category, it is no surprise that diet trends and fads are common in the US. In order to help patients maintain their oral health and prevent negative effects on oral and systemic health, oral health professionals need to be aware of popular diets and determine what, if any impact they may have on the oral cavity.

Ketogenic Diet. One of the more recent diet trends is the ketogenic diet, also known as keto. Often categorized with the Atkins diet, keto is a high-fat, moderate-protein, low-carbohydrate plan. By significantly restricting carbohydrates to 50 g or less per day, the body goes into metabolic physiological ketosis. This is different than the pathological form of ketosis that affects individuals with uncontrolled diabetes. Ketogenesis initiates the breaking down of fats into ketones, which the body then uses as its energy source. When the body burns ketones, it produces acetone, acetoacetate, and beta-hydroxybutyrate. The body flushes out these ketones through exhalation and urination. This can lead to the unpleasant side effect of fruity smelling or acetone scented “keto” breath and xerostomia.8 When the body breaks down protein, it also produces ammonia, which is eliminated through urination and exhalation.9 Ammonia can contribute to oral malodor as well.

Anytime there is an elimination or restriction of specific food groups, nutritional deficiencies become possible. In the case of the ketogenic diet, all carbohydrates including whole grains, fruits, beans/legumes, some nuts, and vegetables are avoided. For patients with diets previously high in refined carbohydrates, this restriction may seem beneficial as it inherently decreases the number of acidic events on enamel due to the absence of fermentable carbohydrate consumption. However, with the restriction of all carbohydrates, including fruits and vegetables, this diet could lead to a reduction of important micronutrients. Vitamin A, found in starchy vegetables, such as carrots and sweet potatoes, helps to build and maintain healthy epithelium.10 Vitamin C, most commonly found in fruits and vegetables, aids with wound healing and resisting infection. Folate found in beans, lentils, and fruit promotes cellular growth and repair.10 When these micronutrients are deficient, there is a depressed anti-inflammatory and immune response, which allows for an invasion of pathogenic organisms, resulting in abnormal redness and bleeding of the oral mucosa (Table 1).10,11 Diets low in antioxidants from eliminating vegetables, fruits, carotenoids, and other nutrient dense foods have been associated with an increased risk of oropharyngeal cancer, the eighth most common cancer in the US.12 Therefore, individuals following a ketogenic diet should consult a nutrition expert to ensure they are getting an adequate amount of these nutrients.

When educating patients on the ketogenic diet, oral health professionals should focus on the need for thorough oral hygiene, especially in the presence of bleeding and xerostomia. To help address keto breath, patients should be encouraged to increase water consumption and eat more healthy fats and less protein.

The Paleo Diet. This eating pattern is often compared to the keto diet, although there are significant differences between the two. Where the keto diet is heavily focused on fat intake, the Paleo diet is primarily a plant-based plan. The diet focuses on eating significant amounts of nutrient-dense foods such as vegetables and fruits, lean meats, and seafood, and eliminating inflammatory foods such as grains, dairy, refined sugars, refined oils, and processed foods.13 In a study by Frassetto et al,14 subjects who followed a Paleo diet for as little as 2 weeks, showed “improvements in blood pressure and glucose tolerance, a decrease in insulin secretion and an increase in insulin sensitivity, and a great improvement in their lipid profiles.” However, with the elimination of grains and dairy, intake of fiber, protein, and calcium may be decreased, all important nutrients for periodontal health.13 By encouraging the increased consumption of green leafy vegetables and lean animal meats, deficiencies are unlikely.

The Paleo Diet. This eating pattern is often compared to the keto diet, although there are significant differences between the two. Where the keto diet is heavily focused on fat intake, the Paleo diet is primarily a plant-based plan. The diet focuses on eating significant amounts of nutrient-dense foods such as vegetables and fruits, lean meats, and seafood, and eliminating inflammatory foods such as grains, dairy, refined sugars, refined oils, and processed foods.13 In a study by Frassetto et al,14 subjects who followed a Paleo diet for as little as 2 weeks, showed “improvements in blood pressure and glucose tolerance, a decrease in insulin secretion and an increase in insulin sensitivity, and a great improvement in their lipid profiles.” However, with the elimination of grains and dairy, intake of fiber, protein, and calcium may be decreased, all important nutrients for periodontal health.13 By encouraging the increased consumption of green leafy vegetables and lean animal meats, deficiencies are unlikely.

Intermittent Fasting. Another common dietary practice is intermittent fasting, an eating pattern in which food intake is limited to a specific number of hours per day. Although a common practice in many ethnic cultures and religions, it recently has become a diet fad used for weight loss. A common pattern is 16:8; however, a variety of methods are used based on personal preference. In the 16:8 intermittent fasting pattern, the person eats during a designated 8-hour time frame and then fasts for the remaining 16 hours.15 This pattern usually follows the circadian cycle, which has been shown to increase weight-controlling hormones, such as human growth hormone and ghrelin. Overnight fasting increases gluconeogenesis, which is the conversion of noncarbohydrate sources into energy, including fat.16 Limiting the eating phase to only 8 hours decreases the length of time the saliva pH drops to an acidic level. During the fasting state, there is a restriction of food and caloric beverages but drinking water is strongly encouraged. Remaining hydrated eliminates xerostomia and helps with normal saliva production, buffering the effects of low pH.

The intermittent fasting diet typically does not prohibit the consumption of specific food groups, it simply restricts the number of hours in which someone can eat. Therefore, the consumption of carbohydrates is not necessarily reduced. Decreased mastication can lead to reduced saliva production, increased risk of xerostomia and caries, and gingival inflammation.17 Oral hygiene instruction and the impact of fermentable carbohydrates in the presence of xerostomia should be the focus of patient education.

Vegetarian/Vegan Diet. There are many types of vegetarian diets, and individuals often choose one based on personal or religious beliefs or due to ethical reasons. For example, a lacto-ovo vegetarian will eat dairy, such as eggs and cheese, but avoids meat, fish, and poultry. A lacto vegetarian is similar but eliminates eggs. Meanwhile, a vegan eliminates all animal products entirely.18 The Academy of General Dentistry notes that patients who follow a vegan or a vegetarian diet may have deficiencies in vitamin D, calcium, vitamin B12, and riboflavin.19 The lack of calcium and vitamin D could result in tooth and bone loss as well as preventing remineralization of susceptible tooth surfaces. Even though vitamin D can be obtained through sunlight and a deficiency is rare, it can occur in people who do not consume milk or fish and avoid or limit sun exposure.19 Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is found in meat, eggs, and dairy products. Glossitis, angular cheilitis, recurrent ulcers, and oral candidiasis are among some of the indicators of a vitamin B12 deficiency.20 Oral health professionals can recognize these signs early and refer for treatment.

Vegetarian diets may negatively impact saliva. In a study published in the Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research, the saliva of vegetarians and nonvegetarians was compared. Results showed that the subjects who remained on vegetarian diets for extended periods gradually lost the ability for their saliva to act as a barrier to free radicals and various bacterial contaminants present in food.21 Another study found that a diet high in antioxidants from fruits and vegetables positively impacted periodontal health by protecting tissues from oxidative damage and altering the inflammatory response in periodontitis.22 However, individuals following a vegetarian diet high in fruit and vegetable consumption, may be more susceptible to tooth erosion.22 Tooth erosion is the dissolution of hard tissues due to consumption of acidic foods and beverages. During enamel erosion, calcium and phosphate are released and demineralization and softening of the tooth surface occurs, increasing sensitivity and the risk for decay.23

Vegetarians and vegans may be at risk for protein deficiency due to the elimination of certain complete protein sources from their diet. Complete proteins contain all nine essential amino acids needed by the body. Protein is critical to the structural integrity and support structures of the dentition and for the resistance of oral pathogens.24 The main sources of complete proteins include meat, cheese, dairy, and eggs. Vegetarians can prevent a protein deficiency by eating a diet rich in whole grains, seeds, nuts, and soy.

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENTS

Taking a nutritional history is an important part of the dental hygiene process of care. In order to assess, plan, and implement dietary guidance, dental hygienists need to determine the best method for collecting nutritional information. Many assessment tools are available online, and the choice will depend on the goals of the assessment, which may include anything from helping patients make better dietary choices to identifying those at risk for malnutrition.

Current dietary intake can be assessed several ways. Asking the patient to recall what he or she ate in the past 24 hours provides a snapshot of the patient’s daily food intake.10 A more involved assessment includes a diet history. This is a questionnaire that identifies usual eating patterns and factors that influence choices, such as convenience, cost, and cultural or religious reasons.10 By understanding patients’ rationale for selecting certain foods, the dental hygienist and patient can determine where changes could be willingly made.

A food frequency questionnaire determines how often a patient eats a particular food. A list of commonly eaten foods is provided, and the patient circles the number of times per day, week, or month he or she consumes that item. This can be completed by the patient in the waiting room and is especially helpful in determining caries risk. For patients who require a more comprehensive dietary assessment, a food diary is an option. Patients record all food and drink consumed for 3 days to 7 days, including a weekend day. Patients are asked to record when the food was eaten along with weighing and measuring the amount consumed. It is the most effective method for gathering dietary information; however, it has the lowest rate of compliance. The burden of recording, weighing, and measuring deters patients from being accurate and they may begin to underestimate food intake and portion sizes.10

NUTRITIONAL COUNSELING

Information gathered during the assessment should be used to determine the effect of dietary practices on oral health. Nutritional counseling should begin with educating the patient about the relationship between diet and oral health. Dental hygienists need to evaluate where patients are in their level of understanding and willingness to change, and then identify specific dietary concerns and provide strategies and resources for addressing them. Effective counseling is often a compromise between clinicians and patients and their environments. Financial resources also influence patient compliance. Scheduling a follow-up appointment for evaluation of patient progress and, if needed, providing a referral to an appropriate health care provider, such as a registered dietitian or nutritionist, are prudent strategies.

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists are well-positioned to identify nutritional deficiencies and behaviors that may impact oral health. Understanding the relationship between nutrition and oral disease helps to identify risk factors and implement strategies to improve both oral and systemic health.

REFERENCES

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020. Available at: health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/introduction/developing-the-dietary-guidelines-for-americans/#stage-3.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- Sheiham A, James WP. A reappraisal of the quantitative relationship between sugar intake and dental caries: the need for new criteria for developing goals for sugar intake. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:863.

- Gupta P, Gupta N, Pawar AP, Birajdar SS, Natt AS, Singh HP. Role of sugar and sugar substitutes in dental caries: a review. ISRN Dent. 2013;2013:519421.

- Nayak PA, Nayak UA, Khandelwal V. The effect of xylitol on dental caries and oral flora. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2014;6:89–94.

- American Academy of Periodontology. Periodontal Disease Fact Sheet. Available at: perio.org/newsroom/periodontal-disease-fact-sheet. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- Najeeb S, Zafar MS, Khurshid Z, Zohaib S, Almas K. The role of nutrition in periodontal health: an update. Nutrients. 2016;8:530.

- Paoli A. Ketogenic diet for obesity: friend or foe? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:2092–2107.

- Solga SF, Mudalel ML, Spacek LA, Risby TH. Fast and accurate exhaled breath ammonia measurement. J Vis Exp. 2014;88:51658.

- Stegeman C, Davis JR. The Dental Hygienist’s Guide to Nutritional Care. 5th ed Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019:186–206, 396–398.

- Sroda R. Nutrition for a Healthy Mouth. Philadelphia; Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006:152.

- Bravi F, Bosetti C, Filomeno M, et al. Foods, nutrients and the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2904–2910.

- Mayo Clinic. Nutrition and Healthy Eating. Available at: mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/paleo-diet/art-20111182. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- Frassetto L.A, Schloetter M, Mietus-Synder M, Morris RC, Sebastian A. Metabolic and physiologic improvements from consuming a paleolithic, hunter-gatherer type diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:1376.

- Purcell S. Intermittent Fasting—healthy or hype? Available at: nutrition.org/intermittent-fasting-healthy-or-hype/. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- Stockman MC, Thomas D, Burke J, Apovian CM. Intermittent fasting: is the wait worth the weight? Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7:172–185.

- Gil-Montoya JA, de Mello AL, Barrios R, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bravo M. Oral health in the elderly patient and its impact on general well-being: a nonsystematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:461–467.

- Wolfram T. Vegetarianism: the basic facts. Available at: eatright.org/food/nutrition/vegetarian-and-special-diets/vegetarianism-the-basic-facts. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- American Academy of General Dentistry. Dentists should advise vegetarians on good oral health. Available at: knowyourteeth.com/infobites/abc/article/?abc=D&iid=315&aid=1273. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- Shipton M, Thachil J. Vitamin B12 deficiency—a 21st century perspective. Clin Med. 2015;15:145–150.

- Amirmozafari N, Pourghafar H, Sariri R. Salivary defense system alters in vegetarian. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2013;3:78–82.

- Palacios C, Joshipura K, Willett W. Nutrition and health: guidelines for dental practitioners. Oral Dis. 2009;15:369–381.

- Baumann T, Carvalho TS, Lussi A. The effect of enamel proteins on erosion. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15194.

- Pflipsen, M., Zenchenko, Y., Nutrition for oral health and oral manifestations of poor nutrition and unhealthy habits. Available at: agd.org/docs/default-source/self-instruction-(gendent)/gendent_nd17_aafp_pflipsen.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2020.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2020;18(4):34-37.

We want to offer you sexual content as well https://hdpornxnxx.org