Stub Out the Tobacco Habit

An evidence-based approach is most appropriate when helping patients quit using tobacco.

This course was published in the November 2014 issue and expires November 30, 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the negative health effects caused by tobacco use and the prevalence of smoking in the United States.

- Identify the health benefits of quitting tobacco use.

- Explain behavioral and pharmacotherapeutic strategies for tobacco cessation.

Since Luther Terry, MD, the United States Surgeon General, first reported the danger of tobacco use in 1964, more than 20 million Americans have died prematurely due to cigarette smoking.1 Smoking causes disease through different pathways. Firsthand smoke is linked causally to 25 health problems, including, but not limited to, cancer of the bladder, cervix, lung, oral cavity, pancreas, stomach and kidney; pulmonary disease; and cardiovascular disease.2 Cigarette smoking causes pregnancy complications, low bone density, ulcers, cataracts, overall diminished health status, and increased morbidity.2 It is associated with diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and colorectal cancer.1 In terms of economic burden, cigarette use creates more than $193 billion in health care costs and loss of productivity annually.1

Secondhand or environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) is associated with cancer, respiratory disease, cardiovascular diseases, and negative effects on the health of infants and children.1 While ETS doesn’t cause periodontal diseases, it increases the risk two-fold of moderate to severe periodontitis—regardless of other contributing factors.3 Tobacco exposure is linked to inflammation and immune system dysfunction.1

According to 2012 data, one in five adults in the US smokes. More men use tobacco than women, although the prevalence of smoking-associated health problems, such as lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cardiovascular disease, is now evenly distributed across both genders due to women’s increased use of tobacco.1,4 There is a relationship between socioeconomic status and tobacco use, as well. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s report Tobacco Use Among US Adults—2012–2013, smoking is most common among American households with annual incomes below $20,000 and the least common among households with annual incomes greater than $100,000.4 Education also affects smoking rates—as education increases, tobacco use declines.4

Interest in quitting tobacco has grown in the US, and societal patterns of its use are changing as more people smoke fewer cigarettes but continue to use nicotine through other avenues, such as e-cigarettes or hookah smoking. Young people often use multiple nicotine-containing products, which increases initiation rates and impedes tobacco cessation.1 At the current rate of smoking cessation in the US, the Healthy People 2020 objective of reducing smoking prevalence to 12% will not be met.5

PROMOTING CESSATION

Encouraging patients to quit smoking is just a small part of health care providers’ responsibility to improve health. The Healthy People 2020 objectives include reducing illness, disparity, and mortality due to tobacco use or secondhand smoke.5 Another objective set by Healthy People 2020 is to increase tobacco screening in dental care settings so that 39.3% of tobacco cessation counseling is offered in the oral health care arena. This would be a 10% increase from the amount provided in dental settings in 2010. Arming patients with quitting strategies and providing assistance are standards of comprehensive care.6

At the heart of the push for tobacco cessation is the danger of exposure to both tobacco and nicotine. Nicotine itself is a powerful drug that has many effects on the body (Table 1). Research suggests that nicotine may be as addictive as heroin, cocaine, or alcohol.7,8 Nicotine use stimulates the release of dopamine, which causes pleasurable feelings. After repeated use, the body begins to develop a tolerance to the effects and “craves” more nicotine to induce the pleasurable feelings. With consistent use of nicotine, the body creates more nicotinic receptors. Thus, over time, tobacco users need more nicotine to achieve the feeling they desire.9

At the heart of the push for tobacco cessation is the danger of exposure to both tobacco and nicotine. Nicotine itself is a powerful drug that has many effects on the body (Table 1). Research suggests that nicotine may be as addictive as heroin, cocaine, or alcohol.7,8 Nicotine use stimulates the release of dopamine, which causes pleasurable feelings. After repeated use, the body begins to develop a tolerance to the effects and “craves” more nicotine to induce the pleasurable feelings. With consistent use of nicotine, the body creates more nicotinic receptors. Thus, over time, tobacco users need more nicotine to achieve the feeling they desire.9

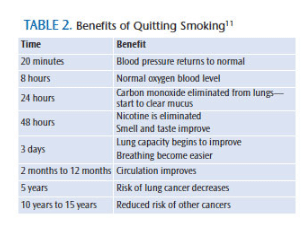

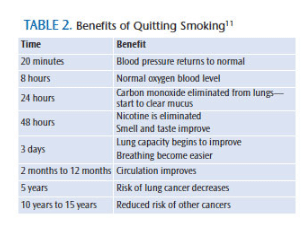

Quitting smoking has immediate, as well as long-term benefits that reduce disease risks (Table 2).1 Smoking harms nearly every organ of the body. In the case of lung cancer, the single largest opportunity to modify risk factors for this particular disease is smoking cessation.10 Individuals who quit by age 30 eliminate nearly all excess risk associated with smoking. Smokers who quit between the ages of 35 and 44 decrease their risk of dying due to smoking-related disease significantly.11 Individuals who quit by age 50 cut in half their risk of dying within the next 15 years.11 As health care providers, dental professionals must discuss the effects of tobacco use with patients and encourage cessation.

Each year, more than half of smokers and tobacco users attempt to quit.1,6 Approximately 69% of adult smokers report they would like to stop tobacco use completely. Unfortunately, less than 10% succeed. Withdrawal symptoms from tobacco use can be difficult for patients to overcome. Symptoms include insomnia, hunger, fatigue, irritability, dry throat, and chest tightness as the body adjusts to the change in nicotine and tobacco consumption.1,7

Between 65% and 75% of smokers who try to quit are unsuccessful because they do not use evidence-based cessation counseling or medications.12,13 In 2010, less than half of smokers who had visited a health care professional in the past year had received advice on quitting.14 As such, many smokers attempt to quit without any assistance, leading to high rates of relapse. Even with multiple interventions, tobacco cessation rates are only between 13% and 25%.7 Many tobacco users will make multiple attempts at quitting before they achieve success, and many will require repeated interventions.1

Between 65% and 75% of smokers who try to quit are unsuccessful because they do not use evidence-based cessation counseling or medications.12,13 In 2010, less than half of smokers who had visited a health care professional in the past year had received advice on quitting.14 As such, many smokers attempt to quit without any assistance, leading to high rates of relapse. Even with multiple interventions, tobacco cessation rates are only between 13% and 25%.7 Many tobacco users will make multiple attempts at quitting before they achieve success, and many will require repeated interventions.1

In order for cessation to be successful, a multifaceted approach should be utilized. Tobacco use creates a dependence and addiction to nicotine, but it has a behavioral component, too. A successful approach for cessation needs to contain components that work for both of these addictions. Cessation counseling and pharmacotherapy are effective in improving quit outcomes. While each approach works separately, their efficacy is much greater when used together.1 The US Public Health Service has developed clinical guidelines that are detailed in the report Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence.7 The guidelines support the use of a combination of prescription medications and behavior counseling, such as motivational interviewing, as the gold standard of smoking-cessation treatment.7

The US Public Health Service has developed the “5 A’s Intervention” (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange) for utilization with current tobacco users or those who have recently quit. Successful intervention begins with identifying which approach is most appropriate based on the user’s willingness to quit.15 This method encourages the clinician to openly discuss tobacco use with patients, inform them of the importance of quitting tobacco, and provide resources and support to begin the process toward a tobacco-free life.

Brief cessation advice and counseling by health care providers can be effective and should be offered.7 Counseling helps control the addictive behaviors associated with tobacco dependence. Studies indicate that 25% of smokers who use adjunctive quit medications stay smoke-free for more than 6 months.16 Success rates tend to increase when used in combination with counseling and other types of emotional support.16 Individual, group, and telephone counseling options are available. The intensity of the counseling, such as the length and number of sessions offered, increases the effectiveness of the cessation attempt.

Telephone quitlines offer counseling that is far reaching and effective with diverse populations.1 Quitlines can serve as a resource for health providers who are only able to briefly discuss intervention and medications; tobacco users can then be linked to quitlines for more intensive counseling.17 One example, 1-800-QUITNOW, is a service offered 24 hours per day, 7 days a week, at no cost.18 This particular quitline employs trained tobacco counselors who answer questions, help callers create a quit plan, and provide support in several languages. Multiple online programs are available for both practitioners and patients that provide guidance on how to quit tobacco, set up tobacco cessation programs in dental offices, and provide educational materials. Agencies—such as the National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, and American Lung Association—provide such programs for little or no cost.19,20 State and local agencies offer assistance to tobacco users through support groups and programs available online or on-site, such as Nicotine Anonymous groups.

CESSATION MEDICATIONS

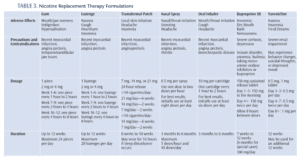

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved seven medications specifically for smoking cessation. Research is still needed to determine their effectiveness in smokeless tobacco cessation. Five of the seven medications are nicotine-replacement therapies (meaning they contain nicotine).14 Nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) are used to reduce physical withdrawal from nicotine. A variety of delivery mechanisms are available for NRTs, including chewing gum, lozenge, transdermal patch, oral inhaler, and nasal spray. Both oral inhalers and nasal sprays are available with prescriptions, while the gum, lozenge, and patch are available over the counter.7 NRTs are available with different levels of nicotine. Patients should choose the nicotine level that best correlates to the number of cigarettes they smoke daily. The length of use among the NRTs varies from a minimum of 8 weeks to 6 months. NRTs are not a quick fix and patients must use them consistently to achieve cessation success.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved seven medications specifically for smoking cessation. Research is still needed to determine their effectiveness in smokeless tobacco cessation. Five of the seven medications are nicotine-replacement therapies (meaning they contain nicotine).14 Nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) are used to reduce physical withdrawal from nicotine. A variety of delivery mechanisms are available for NRTs, including chewing gum, lozenge, transdermal patch, oral inhaler, and nasal spray. Both oral inhalers and nasal sprays are available with prescriptions, while the gum, lozenge, and patch are available over the counter.7 NRTs are available with different levels of nicotine. Patients should choose the nicotine level that best correlates to the number of cigarettes they smoke daily. The length of use among the NRTs varies from a minimum of 8 weeks to 6 months. NRTs are not a quick fix and patients must use them consistently to achieve cessation success.

Two other prescription medications are available that do not contain nicotine. Varenicline is a non-nicotine cessation aid that decreases the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal while blocking the stimulation responsible for reinforcement and reward associated with the pleasurable sensation delivered by smoking.21 Buproprion SR is a slow-releasing tablet that works against the nicotine receptors and can be used in conjunction with NRTs.21

Each medication is used differently and requires that health care providers educate patients on how to use these products. These medications should be used for at least 12 weeks to help with cessation. Each medication has contraindications, warnings, and side effects that should be well known to both patients and health care providers. Patients are advised to work with a health care provider to determine which medications are appropriate to help them in the process of tobacco cessation.

CHANGE IN CESSATION AIDS

As smoking has become less popular, tobacco companies have begun promoting alternative products that are marketed as ways to help individuals reduce or eliminate their smoking habit. Products, such as smokeless tobacco, dissolvable tobacco products (orbs, sticks, and strips), snus, and e-cigarettes, have been introduced by cigarette manufacturers. In regard to smokeless tobacco, manufacturer claims suggest that the risks posed by its use are less than smoking.22 While smokeless tobacco contains less nicotine and no tar or carbon monoxide, these products are addictive and associated with an increased risk of multiple health conditions (oral, esophageal, and pancreatic cancer; myocardial infarction and stroke; oral disease; and reproductive problems).7,23 Promoting tobacco- or nicotine-containing products as cessation aids provides users with an increased risk for multiple negative health outcomes, a false sense of security, and the potential for cancer.

The use of e-cigarettes—a new product that provides nicotine to users through a vapor, as opposed to smoke—is growing in the US. E-cigarette use rose among Americans from 0.6% in 2009 to 2.7% in 2010.24 E-cigarettes contain a cartridge that has nicotine, propylene glycol, an atomizer, and a battery. A vapor results from heating the liquid when users inhale and provides the sensation of smoking. Multiple flavors are available for the nicotine cartridge. The level of nicotine concentration per cartridge is also variable, which has prompted the FDA to begin a review of e-cigarettes and their cartridge contents.25 The research is mixed on whether these devices are effective cessation aids. Though the FDA acknowledges that e-cigarettes may have short-term smoking reduction benefits, the long-term health effects are unknown.26 As nicotine is an addictive agent, the quicker the delivery, rate of absorption, and attainment of high concentrations, the greater the potential for addiction; thus, e-cigarettes need to be further evaluated before being promoted as a cessation strategy. At this time, the FDA does not regulate e-cigarettes, their contents, or the amount of nicotine available.27

Today, apps are available for use with smartphones to promote tobacco cessation. Continued research should be done to determine whether these apps offer evidence-based support for users. The apps need to be based on existing evidence that supports the use of approved medications and counseling, and should be able to connect users to quitlines or support groups with a proven track-record for successful outcomes.28 As smartphones become more ubiquitous, apps may become an increasingly important part of tobacco cessation efforts.

CONCLUSION

As tobacco use continues in the US and around the world, the need for programs to assist health care providers in their ability to support patients in cessation efforts is crucial. Tobacco companies continue to promote their products, which will lead to a new generation of tobacco users.1 Health care providers’ continued advocacy, encouragement to seek counseling, and support in using pharmacotherapy should continue to be the standard of care in tobacco cessation.

REFERENCES

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion US Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion US Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004.

- Sutton JD, Ranney LM, Wilder RS, Sanders AE. Environmental tobacco smoke and periodontitis in U.S. non-smokers. J Dent Hyg. 2012;86:185–194.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Use among US Adults—United States, 2012–2013. Available at: cdc.gov/tobacco/data_ statistics/mmwrs/byyear/2014/mm6325a3/intro.htm. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020 Objectives. Available at: healthypeople.gov/2020/ topicsobjectives2020/default Accessed October 21, 2014

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Office on Smoking and Health. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: the Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010.

- US Public Health Service. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Update 2008. Available at: ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelinesrecommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Nicotine Addiction and Tobacco. Available at: asam.org/advocacy/find-a-policy-statement/view-policy-statement/public-policy statements/2011/12/15/nicotine-addiction-and-tobacco. Accessed October 21, 2014

- Benowitz NL. Neurobiology of nicotine addiction: implications for smoking cessation treatment. Am J Med. 2008:121:S3–S10.

- Jacobson FC, Jaklitsch MT. Tobacco cessation and health promotion. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108:312–314.

- Jha P. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Cancer. 2009; 9:655–664.

- Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1513–1519.

- Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prevent Med. 2008;34:102–111.

- Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Coverage for Tobacco Use Cessation Treatments. Available at: cdc.gov/TOBACCO/ quit_ smoking/cessation/coverage/index.htm. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Five Major Stepts to Intervention. Available at: ahrq.gov/professionals/ cliniciansproviders/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/5steps.html. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- American Cancer Society. Stay Away from Tobacco. Available at: cancer.org/healthy/ stayawayfromtobacco/index. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control. Available at: cdc.gov/tobacco/ stateandcommunity/best_practices/pdfs/2014/comprehensive.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Tobacco Control Research Branch of the National Cancer Institute. 1-800-QuitNow. Available at: smokefree.gov/talk-to-an-expert. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- American Cancer Society. Quit For Life Program. Available at: quitnow.net/Program. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- American Lung Association. Freedom from Smoking. Available at: ffsonline.org. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- University of California, San Francisco. RX for Change. Available at: rxforchange.ucsf.edu. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Mejia AB, Ling PM. Tobacco industry consumer research on smokeless tobacco users and product development. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:78–87.

- Popova L, Ling PM. Alternative tobacco product use and smoking cessation: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:923–930.

- Noel JK, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Electronic cigarettes: a new ‘tobacco’ industry? Tob Control. 2011;20:81.

- Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube DR, Arrazola R. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tob Control. 2013;22:19–23.

- Henry R, Henderson R. The rise of e-cigarettes. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2014;12(5):46–50.

- Federal Register. Deeming Tobacco Products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Regulations on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products. Available at: federalregister.gov/a/2014-09491. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Abroms LC, Padmanabhan N, Thaweethai L, Philips T. iphone apps for smoking cessation—a content analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:279–285.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2014;12(11):60–62,65.