Strategies for the Safe Treatment of Cardiovascular Patients

As the prevalence of heart disease grows, dental hygienists must be aware of its implications for dental care.

This course was published in the May 2015 issue and expires May 31, 2018. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, and myocardial infarction.

- Identify the implications of cardiovascular disease on dental hygiene treatment.

- Discuss the need for adequate anesthesia among patients with cardiovascular disease.

CORONARY HEART DISEASE

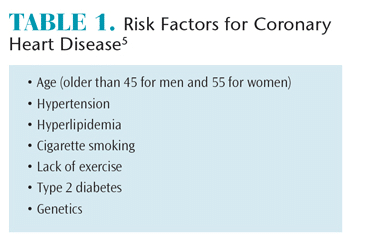

In the US, coronary heart disease, also referred to as ischemic heart disease, has the highest mortality rate of all cardiovascular diseases. In developed countries, coronary heart disease is the leading cause of disability and death and has the largest economic impact of any other disease category.3,4 Table 1 provides a list of risk factors for coronary heart disease.5 This disease is more frequently found in men (9.1%) than women (7%) and women tend to develop the disease approximately 10 years later than men. The estrogen present in premenopausal women may play a protective role.5

In coronary heart disease, the myocardium receives less blood, most commonly due to atherosclerosis, which narrows blood vessel walls partially or fully, blocking blood flow.6 This narrowing occurs over years, and symptoms typically do not manifest unless the coronary artery has been narrowed by at least 70%.7,8

The pathophysiology of coronary heart disease is closely related to inflammation and fatty fibrous plaques progressively narrowing the lumen of coronary arteries.9,10 Atherosclerotic plaques—composed of lipids, white blood cells, smooth muscle cells, connective tissue, and cholesterol—lie under the endothelial lining of the artery wall and develop in three stages.11,12 In stage 1, excess lipoproteins start to accumulate and transpose into arterial walls. Over time, excess fat becomes stuck and forms streaks along the arterial walls. In stage 2, white blood cells respond to the unhealthy masses of lipids. Coronary artery walls become inflamed, increasing the buildup of atherosclerotic plaques.9,10 White blood cells fill up with fat droplets, enlarge, and form foam cells, which are present in the fatty streaks. In stage 3, foam cells secrete substances that cause smooth muscle to migrate into the lining of the artery, causing fatty deposits to thicken, grow in arterial walls, and bulge into the blood stream. This results in a narrowing of the blood vessel.9,13 Subsequently, coronal arteries lose their ability to dilate, causing an imbalance in oxygen supply. Disturbed plaques may also cause blood clots, which can block the artery.8

The pathophysiology of coronary heart disease is closely related to inflammation and fatty fibrous plaques progressively narrowing the lumen of coronary arteries.9,10 Atherosclerotic plaques—composed of lipids, white blood cells, smooth muscle cells, connective tissue, and cholesterol—lie under the endothelial lining of the artery wall and develop in three stages.11,12 In stage 1, excess lipoproteins start to accumulate and transpose into arterial walls. Over time, excess fat becomes stuck and forms streaks along the arterial walls. In stage 2, white blood cells respond to the unhealthy masses of lipids. Coronary artery walls become inflamed, increasing the buildup of atherosclerotic plaques.9,10 White blood cells fill up with fat droplets, enlarge, and form foam cells, which are present in the fatty streaks. In stage 3, foam cells secrete substances that cause smooth muscle to migrate into the lining of the artery, causing fatty deposits to thicken, grow in arterial walls, and bulge into the blood stream. This results in a narrowing of the blood vessel.9,13 Subsequently, coronal arteries lose their ability to dilate, causing an imbalance in oxygen supply. Disturbed plaques may also cause blood clots, which can block the artery.8

Inflammation plays a dominant role in this process, as inflammatory cells migrate to the artery endothelium and cause extracellular molecules to debond within the plaques.8,11,13 This inflammatory response causes the arterial endothelium to demonstrate procoagulant properties instead of anti-coagulant properties, resulting in ruptured plaques and blood clot formation.8,11,13 Periodontal pathogens and associated inflammatory mediators have been implicated in atheroma buildup in blood vessel walls, although the exact relationship between coronary heart disease and periodontitis is still under investigation.12,14–16

ANGINA PECTORIS

Defined as a transient episode of chest pain, angina pectoris is the most common type of coronary heart disease. Chest pain, caused by a temporary interruption of oxygen and nutrients to the myocardium, results from stenosis or spasm of a coronary artery.6,7 Transient ischemia causes weakened myocardial cells at the cellular and tissue levels.8 When the myocardial cells’ demand for oxygen exceeds supply, they become ischemic, which manifests as a burning and/or squeezing that radiates down the ulnar side of the left arm and the mandible. Patients may also report pain in one arm or both, dyspnea, and faintness.17 Rest minimizes the heart’s need for oxygen and often relieves symptoms momentarily as normal blood flow is achieved. If blood flow is not restored, a myocardial infarction results.13 Stable angina is most often associated with exercise, exertion, and emotional upsets, as these stressors can increase the oxygen demand on the heart.8,10,13 Stable angina is predictable and short in duration.

Unstable angina is characterized by angina at rest or upon minimal exertion, new onset of pain, and/or pain that progresses in intensity.11 Indicating severe stenosis of a coronary blood vessel or thrombosis, unstable angina is a major risk factor for a myocardial infarction. Symptoms of heart ischemia that continue after 5 minutes to 10 minutes of rest characterize unstable angina and are caused by disruptions of the atherosclerotic plaques with spontaneous resolution of blockages.12 A key diagnostic feature is the changing pattern of pain.17,18 Patients with unstable angina are not good candidates for routine dental care and only emergency treatment should be implemented in careful consultation with the patient’s physician.17 A hospital or special care site equipped with cardiac monitoring capabilities is recommended for emergency treatment.18

MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

Myocardial infarction (MI), also known as a heart attack, is the most serious manifestation of coronary heart disease. As with angina, MI is associated with atherosclerosis. It is characterized by necrosis of part of the myocardium due to oxygen deprivation.7,9 Clots of atherosclerotic plaques, blood clots, a vasospasm of muscles within the artery walls, or a combination of these factors block the flow of oxygenated blood to the coronary arteries.3,12 If the obstruction persists for more than 30 minutes, the cell injury will be irreversible. Symptoms include intense, acute, and oppressive chest pain that radiates to the back, arms, neck, and mandible.10 Dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, heavy perspiration, and loss of consciousness also occur. As a diagnostic sign, pain is not relieved by rest or nitroglycerin.3 Women may experience different symptoms, including heartburn; malaise; unusual fatigue; dizziness; and neck, jaw, shoulder, upper back, or abdominal pain.19,20

DENTAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT

Patients’ health histories should be meticulously reviewed at each appointment for cardiovascular concerns. Patients who have had an MI in the past 30 days or unstable angina should not be seen for routine preventive dental care.21,22 Emergency treatment should only be conducted in close consultation with the patient’s cardiologist. Each patient’s individual risk should be evaluated prior to treatment to ascertain his or her suitability for elective dental care.22 Levels of functional capacity, severity of the disease, type and length of the dental intervention, stability, last occurrence of a heart-related episode, and cardiopulmonary reserve should be assessed.3 Functional capacity is related to physical activity and whether the activity causes shortness of breath and/or chest pain.

Patients’ health histories should be meticulously reviewed at each appointment for cardiovascular concerns. Patients who have had an MI in the past 30 days or unstable angina should not be seen for routine preventive dental care.21,22 Emergency treatment should only be conducted in close consultation with the patient’s cardiologist. Each patient’s individual risk should be evaluated prior to treatment to ascertain his or her suitability for elective dental care.22 Levels of functional capacity, severity of the disease, type and length of the dental intervention, stability, last occurrence of a heart-related episode, and cardiopulmonary reserve should be assessed.3 Functional capacity is related to physical activity and whether the activity causes shortness of breath and/or chest pain.

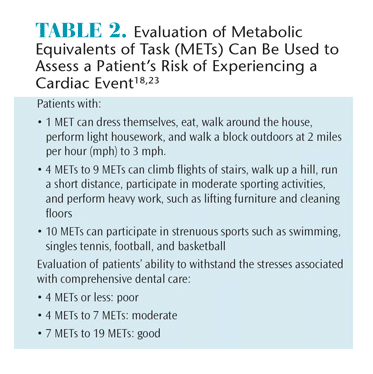

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association have guidelines that measure the energy needed to perform certain tasks in metabolic equivalents of task (MET) or oxygen consumption (Table 2).18,23 MET can be correlated to the patient’s ability to safely withstand the stresses related to dental treatment.18 The lower the score, the greater the risk of problems during dental treatment.18 Scaling and root debridement are low-risk procedures, while maxillofacial surgery with general anesthesia is a high-risk dental procedure. General patient management may also involve consultation with the patient’s physician to assess his or her cardiac status prior to treatment. Assessment of vital signs is imperative; a blood pressure reading over 180/110 mm Hg is a contraindication for treatment.

A thorough review of medication usage and potential side effects and impact on treatment should be reviewed. Patients with cardiovascular disease may be taking ?-adrenergic blocking agents, calcium channel blockers, anti-platelet drugs, statins, and/or nitrates.9 Many of these medications have potential oral side effects. Patients taking long-acting nitrates or calcium channel blockers may experience postural hypotension, which is problematic when patients are returned upright too quickly from a supine position.

Anti-platelet and anti-coagulant medications may cause patients to experience prolonged bleeding, and clinicians should be prepared to implement hemostasis measures. Current thought is that no modification in the anti-platelet medication is needed, as the risk of taking the patient off the medication outweighs the risk of excessive bleeding.9 It is always prudent, however, for the clinician to consult with the patient’s cardiologist.

For patients taking warfarin, obtaining their international normalized ratio (INR) is important. An INR of 3.5 or less is considered safe for invasive dental treatment. Calcium channel blockers contribute to drug-influenced gingival enlargement, although effects may be minimized through effective biofilm control by the patient.

Dental hygiene appointment for patients with cardiovascular disease must be stress-free. The most common cause of emergency during dental care in angina patients is tachycardia associated with psychological or physiological stress.9,17 A key way to control patient stress is through effective pain management. For dental hygienists, scaling and root debridement is the periodontal procedure in which patients most often need pain control. Patients with cardiovascular disease should receive appropriate pain management during scaling and root planing. The anesthesia needs to be of sufficient duration so its effects are maintained throughout the procedure. Otherwise, the unexpected pain experienced with short-lasting agents can result in tachycardia, which may lead to angina.17

The idea that anesthesia containing epinephrine cannot be used in patients with coronary heart disease is outdated. Systematic reviews have revealed no adverse effects of epinephrine in limited doses.24–27 The benefit of incorporating small amounts of epinephrine in local anesthesia administration outweigh the risks, as the endogenous catecholamine released in response to dental pain/stress elevates both blood pressure and heart rate.24–26 Limiting local anesthetic to two cartridges of 1.8 ml of anesthetic with 1:100,000 of epinephrine (0.04 mg) can provide safe, long-lasting pain control during scaling and root debridement for most patients.26,27 Because the combination of epinephrine and digitalis medications can produce arrhythmias, vasoconstrictors are contraindicated in patients taking these drugs.18

The idea that anesthesia containing epinephrine cannot be used in patients with coronary heart disease is outdated. Systematic reviews have revealed no adverse effects of epinephrine in limited doses.24–27 The benefit of incorporating small amounts of epinephrine in local anesthesia administration outweigh the risks, as the endogenous catecholamine released in response to dental pain/stress elevates both blood pressure and heart rate.24–26 Limiting local anesthetic to two cartridges of 1.8 ml of anesthetic with 1:100,000 of epinephrine (0.04 mg) can provide safe, long-lasting pain control during scaling and root debridement for most patients.26,27 Because the combination of epinephrine and digitalis medications can produce arrhythmias, vasoconstrictors are contraindicated in patients taking these drugs.18

Open communication, a trusting relationship between the clinician and patient, soothing music, elimination of extraneous noises, aromatherapy, and anticipatory guidance may promote relaxation and reduce stress during dental hygiene care. The use of anti-anxiety medications taken 1 hour before the appointment may also be warranted. Some patients may be best served by taking a nitroglycerin tablet prior to certain stress-provoking dental procedures.21,22 Nitrous oxide/oxygen sedation is an effective method for controlling anxiety and stress during the appointment. Scheduling is also an important consideration. Short appointments at mid-morning or early afternoon are recommended. Endogenous epinephrine levels peak during morning hours, and research reveals most sudden MIs occur between 8 am and 11 am.21,22 Hence, early morning appointments should be avoided. Using an assistant to facilitate a more efficient and shorter appointment is an additional practical consideration.

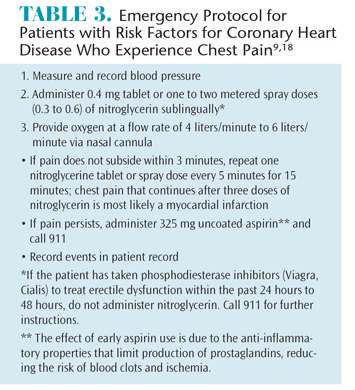

During the appointment, the patient’s nitroglycerin spray or tablets should be available on the bracket table so they can be easily reached. Once opened, nitroglycerin tablets have a 6-month shelf life and the patient’s medication should be examined for expiration date. If the patient’s medication is out of date, the office’s emergency kit supply of nitroglycerin should be substituted. Keeping oxygen close to the operatory is helpful in the event of an emergency.22 Table 3 lists the proper protocol if a patient reports signs of an angina attack, such as discomfort in the chest, arms, and/or neck.9,18

Encouraging effective oral self-care is important to assist patients in maintaining their oral health but also for supporting systemic health. The interrelationship between coronary heart disease and periodontitis should be discussed with patients. To promote overall health and wellness, dental hygienists should focus on promoting lifestyle change that can inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis and the buildup of arterial plaques.28 In general, preventive measures, such as smoking cessation, weight reduction, importance of exercise and consuming a well-balanced diet should be part of the education care plan. The risk of morbidity caused by cardiovascular disease is twice that in smokers vs nonsmokers.18 Patients should also be counseled on the importance of maintaining low blood pressure, reducing cholesterol levels, and controlling diabetes.7,9

SUMMARY

With the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease, dental hygienists can expect to see an increasing number of patients with these conditions. As such, they must understand the effects that cardiovascular disease has on the clinical practice of dental hygiene. Implementing treatment modifications, such as stress and pain management protocols and emergency plans; remaining up to date on the oral and clinical effects of medications used to treat cardiovascular disease; and monitoring blood pressure are necessary to ensure patients receive safe and effective care.

REFERENCES

- Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA. AHA policy statement: forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States. Circulation. 2011;123:933–944.

- National Institutes of Health. 2012 NHLBI Morbidity and Mortality Chart. Available at: nhlbi.nih.gov/research/reports/2012-mortality-chartbook. htm. Accessed February 20, 2015.

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Updated projections of global mortality and burden of disease, 2002-2030: data sources, methods and results. Available at: who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bodprojectionspaper.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2015.

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e2925.

- Emedicine. Coronary heart disease. Available at: emedicinehealth.com/coronary_heart_disease/ article_em.htm Accessed February 20, 2015.

- Singleton J, DiGregoria R, Green-Hernandez C, Holzmer S, Faber E, Ferrara L, Slyer J. Primary Care. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 2015.

- Rosdahi C, Kowalski, M. Textbook of Basic Nursing. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2011.

- Fuster V, Walsh R, Harrington R. Hurst’s The Heart. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hil; 2011.

- Munoz MM, Soriano YJ, Roda RP, Sarrion G. Cardiovascular diseases in dental practice. Practical considerations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:296–302.

- Lynn P. Taylor’s Clinical Nursing Skills. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

- Katz J, Steinberg P. Coronary artery disease. Available at: nursingceu.com/ courses/ 398/ index_ nceu.html. Accessed February 20, 2015.

- Renvert S, Pettersson T, Ohlsson O, Perssonm GR. Bacterial profile and burden of periodontal infection in subjects with diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome. J Periodontol. 2006;77: 1110–1119.

- Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2129–2139.

- Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, et al. The complexity of the periodontal disease— atherosclerotic vascular disease relationship and opportunities for interprofessional collaboration. Circulation. 2012;125:2530–2544.

- Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, et al. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association? Circulation. 2012;125:2520–2544.

- American Academy of Periodontology. Periodontal Disease Linked to Cardiovascular Disease. Available at: perio.org/consumer/AHAstatement. Accessed February 20, 2015.

- Hupp JR. Ischemic heart disease: dental management considerations. Dent Clin N Am. 2006;50:483–491.

- Little J, Falace D, Miller C, Rhodus N. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 8th ed. St Louis: Elsevier; 2013.

- Canto JG, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, et al. Symptom presentation of women acute coronary syndromes: myth vs. reality. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2405–2413.

- O’Keefe-McCarthy S. Women’s experiences of cardiac pain; a review of the literature. Can J Cardiovascular Nurs. 2008;18:18-25.

- Research, Science and Therapy Committee, American Academy of Periodontology. Periodontal management of patients with cardiovascular diseases. J Periodontol. 2002:73:954–968.

- Newman M, Takei H, Klollevold P, Carranza F. Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2015.

- Fleisher L, Beckman J, Brown K, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: executive summary. Circulation. 2007;116: 1971–1996.

- Elad S, Admon D, Kedmi M, et al. The cardiovascular effect of local anesthesia with articaine plus 1:200,000 adrenalin versus lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenalin in medically compromised cardiac patients: a prospective, randomized, double blinded study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:725–730.

- Niwa H, Sato Y, Matsuura H. Safety of dental treatment in patients with previously diagnosed acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:35–41.

- Brown RS, Rhodus NL. Epinephrine and local anesthesia revisited. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:401–408.

- Figallo M, Cayon R, Langares D, Flores J, Portillo G. Use of anesthetics associated to vasoconstrictors for dentistry in patients with cardiopathies. Review of the literature published in the last decade. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4:107–111.

- Mayo Clinic. Coronary Heart Disease. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronaryartery- disease/basics/symptoms/con-20032038. Accessed February 20, 2015.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2015;13(3):44–47.