Strategies for Improving Patient Compliance

Helping patients become intrinsically motivated and encouraging their participation in the decision-making process are both important parts of supporting compliance with oral health care instructions.

Patient compliance is the degree to which an individual adheres to the advice provided by health care professionals. Aside from potentially compromising health, noncompliance is a waste of resources and productivity. The monetary cost of medical noncompliance has been estimated at $300 billion a year.1 In dental hygiene, which is intrinsically focused on prevention, motivating patients to practice healthy behaviors remains a challenging aspect of practice.

A better understanding of human development and the factors that shape human personalities helps improve the understanding of compliance. Most scientific research on human behavior is concentrated on the interval between birth and early adolescence. In the 20th century, the study of human development produced a great deal of work by psychologists such as Sigmund Freud, Erik Erickson, Lawrence Kohlberg, and Jean Piaget. All were influenced, in part, by Darwin’s Theory of Evolution; specifically, that evolutionary processes have not only sculpted the body but also the brain and the behavior it produces.

During an individual’s life, genetic factors interact with cultural contexts (nature vs nurture) to shape behavior. Factors that influence behavior include genetics, culture, religion, education, attitude, environment, parental influence, nutrition, and ability. Health care providers have a responsibility to advise patients how best to prevent oral disease. Ensuring compliance, however, is outside of clinicians’ control.2

For many years, dental hygienists have resorted to fear tactics and the use of worst-case scenarios in order to improve compliance. Research has confirmed what veteran dental hygienists have long known: fear alone seldom works. Not only is fear generally ineffective, it may sabotage compliance.3 Patients are responsible for adopting practices that will improve their health. Indeed, research strongly supports behavioral modification techniques that build on patients’ recognizing the need for change.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature on patient compliance is extensive and spans the fields of psychology, medicine, and consumer behavior. It overwhelmingly addresses compliance in the medical/pharmaceutical fields, however, and not in the areas of dentistry/dental hygiene. In fact, few models specifically address the dentist/dental hygienist-patient dynamic. Regardless, it is possible to extrapolate the key features of medical models and apply them to the dental profession. Gill et al4 identified five key factors of patient care that affect compliance: motivation, relationship, participation, trust, and value.

The word motivation is derived from the Latin term motivus, which means a moving cause. Extrinsic motivation refers to the desire to engage in an activity as a means to an end. Intrinsic motivation is the desire to be involved in an activity for its own sake, and this type provides a stronger stimulus for behavior change. Intrinsic motivation occurs when individuals act without any obvious external rewards. Unfortunately, most adults are not intrinsically motivated to adopt oral hygiene behaviors to promote health. Thus, they must be extrinsically encouraged—a task that is challenging to all health care providers. Increasing intrinsic motivation involves creating attainable goals with personal meaning that provide satisfaction. Positive reinforcement also increases intrinsic motivation; patients enjoy having their accomplishments recognized by others.

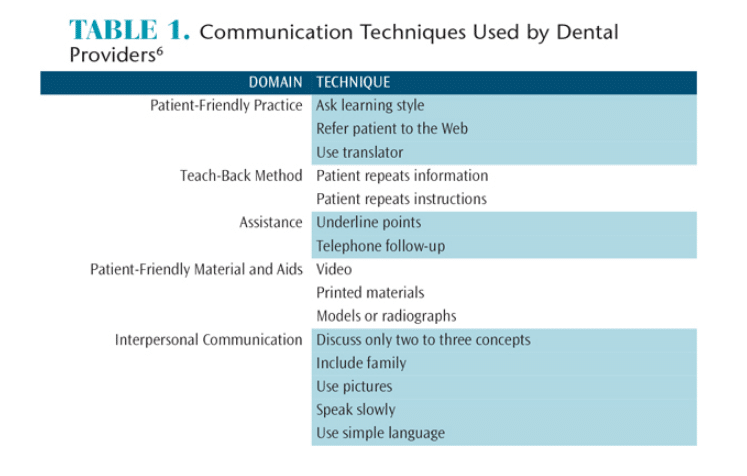

To improve patient compliance, relationships must be built with the practice’s entire staff; not just the provider. Patients who are satisfied with dental care have better compliance, fewer missed appointments, and less anxiety and pain.4,5 Patients want a provider who inspires confidence and who will listen and demonstrate a friendly, caring attitude. They do not want to feel chastised because of past oral health practices. Patients tend to favor ideologies that focus on disease prevention.6 In a study of patient satisfaction involving more than 5,000 individuals, Riley et al6 reported that dentists exhibited a lack of understanding regarding patients’ satisfaction with provided services and poor communication skills. Rozier et al7 surveyed more than 6,000 dentists on their use of basic communicative practices such as speaking slowly and using simple language (Table 1). Their findings showed that in routine practice dentists used only a fraction of the communication techniques during a typical workweek. Additional findings led the authors to conclude that the dental profession should establish and distribute clear guidelines regarding effective communication.

In a study of patient satisfaction involving more than 5,000 individuals, Riley et al6 reported that dentists exhibited a lack of understanding regarding patients’ satisfaction with provided services and poor communication skills. Rozier et al7 surveyed more than 6,000 dentists on their use of basic communicative practices such as speaking slowly and using simple language (Table 1). Their findings showed that in routine practice dentists used only a fraction of the communication techniques during a typical workweek. Additional findings led the authors to conclude that the dental profession should establish and distribute clear guidelines regarding effective communication.

While several researchers have explored the role of gender on dental treatment compliance, there appear to be no differences. Men and women have comparable levels of adherence to protocols and recommendations.8,9 Women providers are more likely to engage in longer discussions regarding treatment options and materials than their male counterparts.6,10 Additionally, women providers offered greater reassurance and encouragement.4,6

Participation involves the patient’s involvement in the health care decision-making process.11 A patient’s active involvement in the dental care process is associated with positive outcomes. The literature is strong on the need for health care providers to abandon the paternalistic model of care in which the patient’s voice is not valued.

Patients who firmly believe in the judgment of a health care provider are more inclined to follow treatment recommendations. Trust is a product of ongoing interaction and discussion and depends on the disposition of both parties. Dy and Purnell12 identify the key components of trust as fidelity, competence, honesty, and confidentiality.

Patients derive value from the benefits they receive from treatment. Krisjanous and Maude13 note, “Value cannot be found in an object or product (including a service) per se, but is the phenomenological experience of the customer’s interactive and relativistic consumption of it.” Value is encounter specific and determined by the patient during the process of care.

THEORETICAL MODELS

The medical literature has suggested various models of behavior change with little to no research on their applications in dentistry and dental hygiene. In contrast, motivational interviewing has been studied in the dental environment. The latter method has grown in popularity due to its focus on enhancing the intrinsic motivation of patients and has been successful in helping patients overcome addictions. In a meta-analysis of randomized control trials, researchers discovered that motivational interviewing had a significant and clinically relevant effect in treating behavioral problems and diseases.14 In the practice of dental hygiene, motivational interviewing can assist patients in finding cognitive and behavioral techniques that, when combined with the delivery of dental care, provide dental hygienists with the ability to support behavior change.15 The goal of motivational interviewing is to have patients voice the need for behavior change. This is called “change talk” and is done after all assessments have been completed.

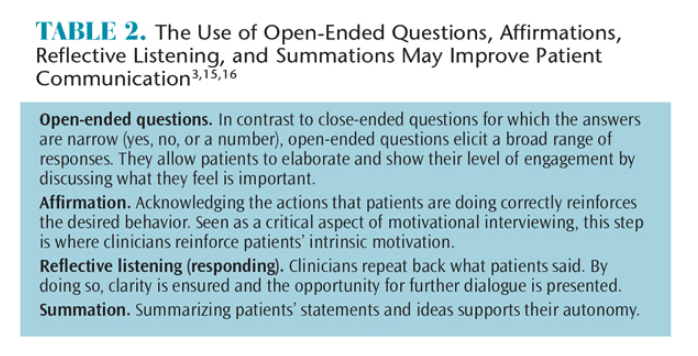

Unlike the paternalistic model in which providers make decisions regarding care without involving patients, modern providers are encouraged to use open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summations (OARS). Table 2 defines these concepts.3,15,16 For example, Mr. Jones has type I diabetes with mild-generalized inflammation and bleeding and moderate generalized plaque. Sally, the dental hygienist, has determined (through her assessments) that the target behavior is the twice daily use of a power toothbrush for 2 minutes and the daily use of floss. She offers information regarding the connection between periodontal diseases and diabetes, methods to remove oral biofilm, and the various aids available. Instead of telling the patient what to do, she begins a conversation (utilizing open-ended questions) with Mr. Jones about what he understands thus far (reflective listening) and asks what his feelings are regarding the provided information. Sally gives less attention to the patient’s responses if they do not support change, perhaps by asking evocative questions such as: “What do you see as the worst thing that can happen if you don’t make a change?” She also reinforces responses (affirmation), which voluntarily speak of reasons to change:

Mr. Jones: “I didn’t know that keeping my teeth clean would help me control my diabetes. I will make sure I use the power toothbrush the right way.”

Sally: “Using a power toothbrush is an excellent way to remove plaque and prevent inflammation. Great idea!”

Becoming truly proficient in the application of motivational interviewing requires commitment and training. Miller et al17 reported that competency-based clinical supervision improves clinicians’ motivational interviewing skills. Additionally, written feedback and telephone coaching following participation in a motivational interviewing workshop increased proficiency (as opposed to no follow-up support).18 Training in motivational interviewing is provided through the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers, a nonprofit organization whose members are certified to provide training, coaching, and consultation after demonstrating their own mastery of motivational interviewing techniques.

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists who base their care on respect and acceptance of patients’ autonomy will establish successful relationships and increase patient compliance. Research has shown that compliance increases when patients are intrinsically motivated, engaged by trusted practitioners, and actively participate in the decision-making process. Medical models of communication to increase compliance provide dental hygienists with a strong theoretical framework to build on. The goal of motivational interviewing is to elicit behavioral change, using the OARS methodology, in order to better communicate with patients. No single communication technique is effective with all patients. Dental hygienists must combine these techniques with their own clinical experience for optimal outcomes.

References

- DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209.

- Jönsson B, Ohrn K, Oscarson N, Lindberg P. An individually tailored treatment program for improved oral hygiene: introduction of a new course of action in health education for patients with periodontitis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009;7:166–175.

- Brand VS, KK Bray, MacNeill S, Catley D, Williams K. Impact of single?session motivational interviewing on clinical outcomes following periodontal maintenance therapy. Int J Dent Hyg. 2013;11:134–141.

- Gill L, Cassia F, Cameron ID, Kurrle S, Lord S. Exploring client adherence factors related to clinical outcomes. Australasian Marketing Journal. 2014;22(3):197–204.

- Sbaraini A, Carter SM, Evans RW, Blinkhorn A. Experiences of dental care: what do patients value? BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:177.

- Riley JL, Gordan VV, Hudak-Boss SE, Fellows JL, Rindal DB, Gilbert GH, National Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative Group. Concordance between patient satisfaction and the dentist’s view: Findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:355–362.

- Rozier RG, Horowitz AM, Podschun G. Dentist-patient communication techniques used in the United States: the results of a national survey. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:518–530.

- Ojima M, Hanioka T, Shizukuishi S. Survival analysis for degree of compliance with supportive periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:1091–1095.

- Famili P, Short E. Compliance with periodontal maintenance at the University of Pittsburgh: Retrospective analysis of 315 cases. Gen Dent. 2009;58:e42–47.

- Elderkin?Thompson V, Waitzkin H. Differences in clinical communication by gender. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:112–121.

- Longtin Y, Sax H, Leape LL, Sheridan SE, Donaldson L, Pittet D. Patient participation: current knowledge and applicability to patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010; 85:53–62.

- Dy SM, Purnell TS. Key concepts relevant to quality of complex and shared decision-making in health care: A literature review. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:582–587.

- Krisjanous J, Maude R. Customer value co-creation within partnership models of health care: an examination of the New Zealand Midwifery Partnership Model. Australasian Marketing Journal. 2014;22(3):230–237.

- Rubak S, Sandbæk A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J R Coll Gen Pract. 2005;55:305–312.

- Jönsson B, Ohrn K, Oscarson N, Lindberg P. An individually tailored treatment program for improved oral hygiene: introduction of a new course of action in health education for patients with periodontitis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009;7:166–175.

- Darby ML, Walsh M. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014.

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1050–1062.

- Martino S. Strategies for training counselors in evidence-based treatments. Addict Sci Clin Prac. 2010;5:30–39.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2015;13(12):27–29.