Strategies to Address Periodontally Involved Furcations

While treating periodontally involved furcations is fraught with challenges, several approaches are available to achieve the best possible patient outcomes.

This course was published in the August 2021 issue and expires August 2024. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss molar furcation management.

- Identify how collaborative multidisciplinary care contributes to successful treatment of this patient population.

- Describe indications and contraindications for odontoplasty when treating patients who present with periodontally involved furcations.

Addressing a periodontally involved furcation presents unique challenges, including the difficulty, if not impossibility, of achieving complete plaque and calculus removal within the compromised furcation;1–6 inability of the patient to predictably keep plaque from repopulating the furcation and periodontal pocket;7 and unique hindrances to plaque removal and control due to the local morphology of the furcation, such as fluted roots, cementoenamel projections, or enamel pearls. These challenges lead many clinicians to attempt to “maintain” teeth with furcation involvement until the only predictable therapy is extraction and replacement. Unfortunately, delaying effective therapy leads to progression of periodontal destruction,8–10 possible compromise of periodontal support of adjacent teeth, and increased risk of patient discomfort as problem areas become more active.

The relative ineffectiveness of scaling and root planing in the management of furcation-involved teeth and the increased incidence of multirooted tooth loss (as compared to their single-rooted counterparts) have been documented in a number of studies.11–13 Such attempts at maintenance of the periodontally involved furcation rarely result in positive outcomes.

Fortunately, the predictability of various treatment modalities in given clinical scenarios has stood the test of time.14–18 As important is the fact the profession also has a large body of knowledge regarding which therapies are less effective in specific situations and in distinct patient populations.

Any therapy in the area of a tooth with a periodontally involved furcation must be carried out in the context of a thorough, multifactorial examination and diagnosis, shared treatment planning and decision-making, and multidisciplinary delivery of therapies.

Novel Furcation Classification System

Many furcation classification systems of various complexities exist.19–21 We use the following simplified classification system for periodontally involved mandibular furcations, as it offers the advantage of direct applicability with regard to predictable treatment options.

I. Horizontal furcation involvement

A. Class I: Entrance into the furcation proceeds less than half of the horizontal dimension of the tooth (Figure 1).

B. Class II: Entrance into the furcation proceeds greater than half of the horizontal dimension of the tooth, but less than the full horizontal dimension of the tooth (Figure 2).

C. Class III: Entrance into the furcation proceeds around to complete the horizontal dimension of the tooth, connecting the buccal and lingual furcation entrances (Figure 3).

II. Vertical furcation involvement

A. Loss of less than 25% of the vertical component of the attachment apparatus in the furcation.

B. Loss of between 25% and 50% of the vertical component of the attachment apparatus in the furcation.

C. Loss of more than 50% of the vertical component of the attachment apparatus in the furcation.

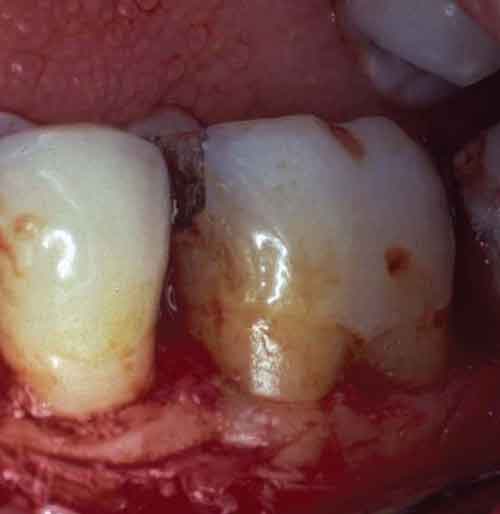

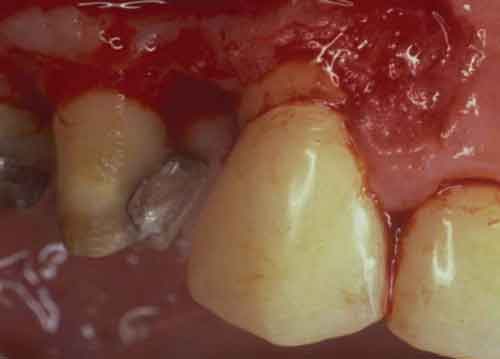

Class I Buccal and/or Lingual Furcation Involement

Class I furcation involvements are predictably treated through odontoplasty, in which the roof of the furcation is recontoured to eliminate the cul-de-sac that traps plaque in a vertical dimension.14,18 The newly established tooth contours must be carried onto the radicular surface to create a blended continuous morphology conducive to patient plaque control. In the course of odontoplasty, any cementoenamel projections are eliminated (Figure 4 through Figure 7). If the tooth was not already planned for restoration, elimination of Class I furcation involvements through odontoplasty does not necessitate restoration of the reshaped area.

If restoration is planned, the tooth must be managed in a manner that combines various tooth preparation designs.14,18 Clinicians will choose their conventional crown preparation (whether it be chamfer, butt joint, or another approach) in all areas except where odontoplasty has been carried out. Due to the reduced thickness of tooth structure following odontoplasty, this area will be treated with a feather edge or shallow chamfer to avoid undue compromise of intact tooth structure and resultant pulpal exposure. The casting is shaped to mimic these newly developed contours, with a flat emergence profile coming out of the sulcus for approximately 2 mm in the area of odontoplasty before smoothly transitioning to more conventional crown morphologies (Figure 8, and Figure 9).

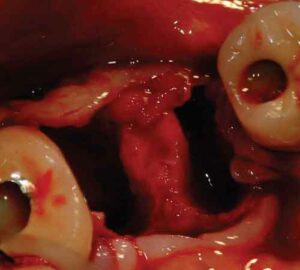

Class II Buccal and/or Lingual Furcation Involvement

When presented with a Class II furcation, the team must assess a number of treatment options. Odontoplasty cannot be employed to eliminate the “roof” of the periodontally involved furcation, as the resultant tooth contours would be characterized by a deep notch that would retain plaque. If the tooth has a favorable prognosis with treatment, a combination of odontoplasty to reduce the horizontal component of the furcation, followed by regenerative surgery or root resection, can be completed.22 If the prognosis is unfavorable with these methods, tooth removal and replacement must be employed (Figure 10 through Figure 12).

If the vertical component of the furcation involvement, in combination with the overall treatment plan, warrant attempts at maintaining a tooth with a Class II furcation involvement, odontoplasty is performed to the depth which will be employed to eliminate a Class I furcation. Regenerative periodontal therapy is then carried out in the reduced (and thus more predictable) furcation defect. The same restorative principles regarding appropriate preparation designs are followed, as in the instance of eliminating a Class I furcation via odontoplasty.

Tooth Removal and Replacement With an Implant Prothesis

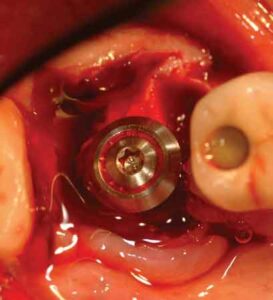

If the tooth in question demonstrates a Class II furcation involvement characterized by such periodontal destruction as to render it nonmaintainable, or if a Class III furcation involvement is present, the tooth is extracted and regenerative therapy performed before it is replaced with an implant, abutment, and crown. The question then becomes whether to place the implant at the time of tooth removal and perform regenerative therapy in the residual extraction socket defect, or rebuild alveolar bone in the region through regenerative therapy and place the implant during a second surgical visit.23

Immediate implant placement requires ideal positioning of an appropriate diameter implant for the tooth being replaced. If there is any doubt regarding the ability to attain this goal, an implant is not placed at the time of mandibular molar extraction. Rather, regeneration is accomplished, and the implant is placed after sufficient healing of the regenerated bone.

Following osseointegration of an ideally positioned implant in a molar socket, restorative therapy is completed. Ideally, an implant design that allows the crown to rest on the neck of the implant is preferable in these areas, as studies have demonstrated a reduction of stresses to both the peri-implant crestal bone and abutment interface when the crown rests on the implant body rather than the abutment (Figure 13 through Figure 18).

Conclusion

As with most dental treatment, comprehensive periodontal care typically begins in the restorative practice. It is the restorative dental teams who must recognize furcation involvements as early as possible, minimizing the extent of care required to predictably keep the tooth. It is the restorative dental teams who must be well versed in the indications and contraindications of each treatment modality as it relates to the individual patient. Explaining patient needs and motivating the patient to see a specialist also fall on the restorative dental team. Following the appropriate referrals, all team members must discuss the challenges faced and formulate a unified, comprehensive treatment plan. Execution of the treatment plan is multidisciplinary. Through comprehensive understanding, effective communication, and patient-centered care, the extended clinical team can help maximize treatment success while minimizing trauma.

References

- Waerhaug J. Healing of the dento-epithelial junction following subgingival plaque control. II: As observed on extracted teeth. J Periodontol. 1978;49:119–134.

- Stambaugh RV, Dragoo M, Smith DM, Carosali L. The limits of subgingival scaling. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1981;5:30–42.

- Buchanan S, Robertson P. Calculus removal by scaling/root planing with and without surgical access. J Periodontol. 1987;58:163.

- Caffesse R, Sweeney PL, Smith BA. Scaling and root planing with and without flap surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:205–210.

- Rabbani GM, Ash MM, Caffesse RG. The effectiveness of subgingival scaling and root planing in calculus removal. J Periodontol. 1981;52:119–123.

- Jones WA, O’Leary TJ. The effectiveness of root planing in removing bacterial endotoxin from the roots of periodontally involved teeth. J Periodontol. 1978;49:337–342.

- Tabita PV, Bissada NF, Maybury JE. Effectiveness of supragingival plaque control in the development of subgingival plaque and gingival inflammation in patients with moderate pocket depth. J Periodontol. 1981;52:88–93.

- Hirschfeld l, Wassermann B. A long-term study of tooth loss in 600 treated periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1978;49:225–237.

- Goldman MJ, Ross IF, Goteiner D. Effect of periodontal therapy on patients maintained for 15 years or longer. A retrospective study. J Periodontol. 1986;57:347–353.

- McFall W Jr. Tooth loss in 100 treated patients with periodontal disease. A long-term study. J Periodontol. 1982;53:539–549.

- Fleischer HC, Mellonig JT, Brayer WK, Gray JL, Barnett JD. Scaling and root planing efficacy in multirooted teeth. J Periodontol. 1989;60:402–409.

- Newell D. Current status of the management of teeth with furcation invasion. J Periodontol. 1981;52:559–568.

- Waerhaug J. The furcation problem. Etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, therapy and prognosis. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:73–95.

- Rosenberg MM, Kay HB, Keough BE, Holt RL. Periodontol and Prosthetic Management for Advanced Cases. Chicago: Quintessence; 1988:247–298.

- Becker W, Becker B, Ochsenbein C, et al. A longitudinal study comparing scaling and osseous surgery and modified Widman procedures. Results after one year. J Periodontol. 1988;59:351–365.

- Kaldahl WB, Kalkwarf KL, Kashinath DP, Molvar NP, Dyer JK. Long-term evaluation of periodontal therapy: I. Response to 4 therapeutic modalities. J Periodontol. 1996;67:93–102.

- Olsen CT, Ammons WF, van Belle G. A longitudinal study comparing apically repositioned flaps, with and without osseous surgery. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1985;5:10–33.

- Fugazzotto PA. Chapter 3 Treating the Periodontally Involved Furcation. In: Periodontal-Restorative Interrelationships: Ensuring Clinical Success. Wiley Blackwell: Ames, Iowa; 2011:89–113.

- Pilloni A, Rojas MA. Furcation involvement classification. A comprehensive review and a new system proposal. Dent J (Basel). 2018;6:34.

- Graetz C, Mann L, Krois J, et al. Comparison of periodontitis patients’ classification in the 2018 versus 1999 classification. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46:908–917.

- Tarnow D, Fletcher P. Classification of the vertical component of furcation involvements. J Perio. 1984;55:283–234.

- Fugazzotto PA. Decisions Making at the Time of Treatment of Furcated Mandibular Molars: Roles of Resective, Regenerative, and Implant Therapies. In: Implant and Regenerative Therapy in Dentistry: A Guide to Decision Making. Wiley Blackwell: Ames, Iowa: 2009:248.

- Fugazzotto PA. Implant placement at the time of mandibular molar extraction. J Periodontol. 2008;79:737–747.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2021;19(8):36-39.