EPITAVI/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

EPITAVI/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Remembering Your Roots

A keen understanding of root morphology and how it provides hiding places for biofilm and calculus is integral to successful patient outcomes.

Scaling and root planing poses many challenges to even the most talented clinicians. One significant stumbling block is the fact that the procedure is done blind with the clinician relying almost entirely on tactile sensation and clinical expertise to produce a clean root surface. As such, procuring a deep understanding of root morphology and how it provides hiding places for biofilm and calculus deposits is key to successful outcomes.

Knowledge of root morphology is important when planning for periodontal instrumentation. As the study of dental root anatomy is usually introduced early in dental hygiene training, it’s easy to forget its intricacies.1 In addition, evaluation of root proximity and the position of crowns in the dental arch are also key to effective periodontal instrumentation.2–4 This article will review root morphology and how it impacts patient care. Instrument selection should be modified based on root contours, shape, and tooth location in the dental arch.

The Basics of Root Morphology

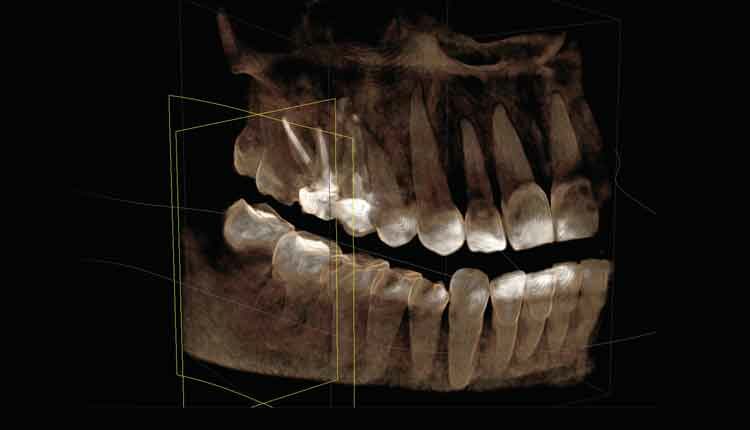

To start, reviewing patients’ current probing depths will provide insight to morphological traps to biofilm and calculus. As pocket depths increase so does complex root anatomy and the number of root concavities.5 Caffesse et al5 found that in pockets greater than 5 mm, total root debridement drops to 32% due to the increase of complex root morphology. In patients with periodontal diseases, more root anatomy is exposed; however, more space may be available to insert and adapt the curet.2 Radiographs provide valuable information about root shape, root proximity, and crown contour. Based on these findings, clinicians can assess which instruments are best suited for complete periodontal instrumentation.

Clinicians should envision the shape and location of the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) on each tooth surface. The anatomy of the CEJ varies from tooth to tooth. Curvature of the CEJ is greatest on the anterior teeth due to the narrow profile of these teeth.4,6 The height of the distal aspect’s curvature on the anteriors is usually 1 mm less than that of the mesial aspect.4,6 Posterior teeth have flatter CEJ curvatures on the interproximal aspects of the teeth than the anteriors (Figure 1).6

Root concavities occur mostly on the proximal surfaces, rendering them less accessible for patient self-care and clinician instrumentation. In general, mesial roots have deeper concavities than distal roots surfaces. General root shape will be presented here; however, clinicians should note that root morphology is unique to each patient (Figure 2).3,6

Single-Rooted Teeth

The roots on single-rooted teeth are cone shaped and have three basic root forms when accessed at the CEJ. Triangular shapes are most common in the maxillary incisors.4,6 The roots have a broad facial aspect with equal sides on the mesial and distal. They are narrow on the palatal/lingual aspect where clinicians may find instrument adaptation the most challenging. Ovoid shapes have broader mesial and distal aspects followed by a narrower facial aspect than that of the triangular shapes, in addition to a narrow palatal/lingual root. Canines exhibit this shape. Mandibular incisors and maxillary bicuspids are elliptical in shape.4,6 The mesial and distal sides are equal in size but the facial and lingual aspects are narrow.4

When instrumenting the maxillary incisors, clinicians should be mindful of the high CEJ curvature on the mesial of the central incisor.4,6 Also, the narrow palatal root may require special attention and a mini-bladed instrument to move around this narrow root shape. The maxillary lateral incisor may have a palatal/gingival groove that will start on the crown and extend subgingivally.3 Assessment of the crown will show a deep groove; probing in alignment with this groove may reveal a narrow deep pocket following the path into a root groove. The crown of the maxillary canine has a distal flair at the CEJ, which makes accessing the mesial of the first bicuspid more difficult.3,4,6

Mandibular anteriors have extremely narrow roots. Access with standard Gracey curets is limited due to their bulky shape. Mini or micro-mini Graceys should be considered. Mandibular canines and bicuspids have fewer root concavities than their counterparts in the maxillary arch. However, the mandibular first premolar may have a deep mesial groove in deeper pocket areas.3,4,6

Multi-Rooted Teeth

The maxillary first premolar has a prominent mesial concavity that starts at the CEJ. Furcation involvement is usually in the apical one-third of the tooth. The entrance to the furcation is located 6 mm apical to the CEJ.3,4 It has narrow facial and palatal root surfaces that may make complete instrumentation difficult.3

The maxillary first molar has a number of root concavities and furcations. The deeper concavities are located on the mesiobuccal root and, more frequently, on the palatal root.4,6 Careful exploring is needed to detect residual deposit on these surfaces. Horizontal strokes or the use of a mini Gracey may help to remove calculus lodged in grooves. The opening into the mesial furcation is more coronal than the entrance to the distal furcation. Furcation entrances are approximately 3 mm from the CEJ on the mesial surface, 4 mm on the buccal surface, and 5 mm from the CEJ on the distal surface.2,3,4,7 Moderate bone loss on the mesial surface can result in early furcation involvement. The mesial furcation opens toward the palate while the distal furcation open distally (Figure 3, page 21). The mesiobuccal root is the largest of the three roots comprising two-thirds of the total root trunk. The mesial furcation should be approached from the palatal aspect of the tooth because of the entrance’s location and increased interproximal space due to the flair of the roots.8 The first maxillary molar has a hidden internal concavity on the mesiobuccal root.3 This depression may be difficult to reach (Figure 4).

The maxillary second molar is similar to the first molar, however, it is more common for the roots to be close together or fused. The entrance to the furcations occurs more apically than on the first maxillary molar, but the furcations have a similar shape to that of the maxillary first molars.3

The mandibular first molar has a short root trunk, with the buccal furcation entrance located about 3 mm from the CEJ and a lingual entrance about 4 mm.3,4,7 A prominent buccal concavity exists just below the CEJ, leading into the buccal furcation. Concavities may also be present on the inside of the furcation walls. The entrance into the furcation can be narrow, making instrument angulation challenging. This tooth will have an enamel projection into the furcation 28.6% of the time (Figure 5).3,9 If the patient presents with an isolated furcation involvement of the mandibular first molar, an enamel projection may be present. In mandibular first molars with periodontal involvement isolated to the furcation, 90% are associated with enamel projections.3,9

Second mandibular molars are similar in shape to mandibular first molars. There is a higher incidence of fused roots and more closed furcation entrance than seen in the first mandibular molar.3

In long-term maintenance studies, molars are the most likely to be lost, especially maxillary first and second molars due to uncontrolled periodontal disease.7,9,10 Furcation involvement is the most common link to periodontal disease-related tooth loss.2,9,11

Instrumentation

Root size and shape are important to consider when selecting instruments. Smaller instruments will fit into narrow concavities and furcations. Remembering the location of furcation entrances may impact the approach to a particular area. Some roots are easier to scale by accessing surfaces from the palatal/lingual side.12,13 Furcation morphology can be complex, so a review of root structure may be helpful.

The use of an ultrasonic insert/tip (UIT) in overlapping, multidirectional strokes may be the best approach to instrumenting furcations.8,13 The left and right curved UITs are thin and may be easier to adapt to the varied root morphology found within the furcation areas than hand instruments.8 As UITs can be used at 0° to 15° of angulation, access to narrow pockets is improved. There may be less risk of burnishing calculus with a UIT due to inability to achieve proper scaling angulation with a manual curet.8,12

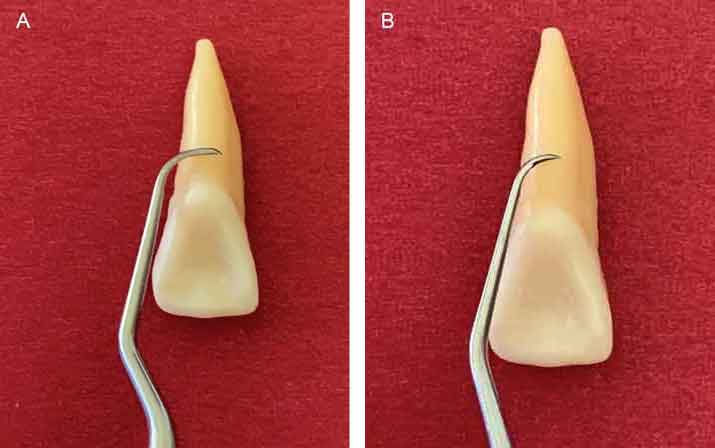

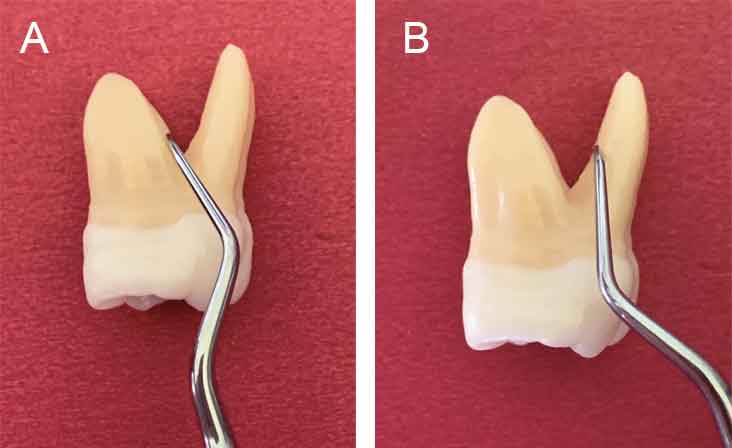

When hand scaling, mini or micro-mini Graceys will improve access to deeper pockets and adaptation to the root morphology (Figure 6A and Figure 6B).8,12,13 The mini/micro-mini 13/14 Gracey can be adapted to most areas of furcation involvement (Figure 7A and Figure 7B). A universal curet can be used with horizontal strokes, especially at the entrances to buccal or lingual furcations, as well as at the CEJ. Instruments designed to improve access to furcations should be considered. Diamond-coated instruments can be used with light pressure as finishing instruments.13 Caution should be exercised when using diamond-coated instruments in order to not over-instrument the roots. Maintaining proper blade angulation and instrument sharpness, in addition to selecting the correct blade size are critical to success.

Whether using manual or power scaling, overlapping channel strokes are critical to instrumenting the entire root surface.8,13 Tactile sense and careful multidirectional strokes will aid in complete calculus removal. Remembering root morphology, reviewing radiographs, and using current probe readings will also help achieve complete root instrumentation. Air may be used to retract tissue to visually inspect the root.

Conclusion

Maintenance for patients with periodontal diseases requires highly skilled clinical care and diligence with self-care regimens. Dental hygienists focus on removing biofilm and calculus deposits that patients are unable to remove on their own. When there is apical migration of the epithelial attachment, more complex root morphology is revealed, making it easier for biofilm and calculus to form.2,3,4,12

When developing the scaling approach for patients with periodontal diseases, remembering root morphology is paramount. The morphology may vary from patient to patient; however, basic similarities exist with each tooth that may help guide instrument selection and scaling method. Reviewing root morphology and following the individual characteristics of each root form will assist clinicians in achieving successful outcomes with nonsurgical periodontal therapy.

References

- American Dental Association. CODA Dental Hygiene Standards. Available at: ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/dental_hygiene_standards.pdf?la=en. Accessed August 11, 2021.

- Kadovic J, Novakovic N, Jovanci M, et al. Anatomical characteristics of the furcation area and root surfaces of multi-rooted teeth: epidemiological study. Vojnosanitetski Pregled. 2019;76(8):761–771

- Gher ME, Vernino AR, Root morphology—clinical significance in pathogenesis and treatment of periodontal disease. J Am Dent Assoc. 1980;101:627–633.

- Bryan LB. Root morphology and instrumentation implications. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM, eds. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2015.

- Caffesse RG, Sweeney PL, Smith BA. Scaling and root planing with and without periodontal flap surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:205–210.

- Nelson SJ, Ash MM. Wheeler’s Dental Anatomy, Physiology, and Occlusion. 9th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2010.

- Karthikeyan BV, Sujatha V, Prabhuji MLV. Furcation measurements: realities and limitation. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2015;17:103–115.

- Caganap K, Beleno-Sanchez J, Nguyen M. Troubleshooting instrumentation of furcations, concavities, and depression. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2015;15(7):28–30.

- Martos J, Leonetti ACM, Netto MSG, Cesar Neto JB, Nova Cruz LER. Anatomical evaluation of some morphological abnormalities related to periodontal diseases. Brazilian Journal Morphological Science. 2009;26(2):77–80.

- Upadhyaya C, Humagain M. The pattern of tooth loss due to dental caries and periodontal disease among patients attending dental department (OPD), Dhulikhel Hospital, Kathmandu University Teaching Hospital (KUTH), Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2009;7:59–62.

- Ong G. Periodontal disease and tooth loss. Int Dent J. 1998;48(Suppl 1):233–238.

- Hou GL. Root topographic study on molars with furcation involvements in taiwanese adults: a risk analysis of furcation entrance dimension and root trunk length. International Journal of Dentistry and Oral Health. Available at: sciforschenonline.org/journals/dentistry/IJDOH337.php. Accessed August 11, 2021.

- Hodges K. The challenge of furcations. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2008;2(6):34–38.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2021;19(9):18, 21-23.