MARTIN IVANOV / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

MARTIN IVANOV / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

Reduce the Prevalence of Early Childhood Caries

While the expansion of Medicaid and The Children’s Health Insurance Program has improved utilization of dental care, state disparities remain.

This course was published in the June 2016 issue and expires June 30, 2019. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the federal laws designed to improve access to oral health care for children.

- Define early childhood caries (ECC).

- Discuss the evidence-based recommendations for treatment of ECC.

- Explain the impact of public programs on the prevalence of ECC.

Two major federal laws—the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA) of 2009 and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010—have great potential to improve the oral health of children at high risk for early childhood caries (ECC). CHIPRA provided states with new funding, program options, and incentives for providing health and dental care services to children in low-income families. The ACA of 2010 increased the number of children covered by Medicaid, primarily through simplifying the enrollment process and increasing outreach. Together, these two laws removed barriers to care for some of America’s most vulnerable children. This paper summarizes current knowledge about ECC and discusses the improvements that have been made in the caries status of young children in the United States, as well as goals that still need to be accomplished.

EARLY CHILDHOOD CARIES

Dental caries is a common chronic and transmissible disease resulting from bacterial biofilms that adhere to teeth and metabolize sugars to produce acid, which, over time, demineralizes tooth structure.1 Based on recommendations made during a conference hosted by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), ECC has been operationally defined as the presence of one or more decayed (noncavitated or cavitated lesions), missing (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a child younger than 72 months.2

Table 1 lists the variables that may directly or indirectly influence the risk for ECC.3 While relatively inexpensive to prevent, ECC remains among the most prevalent chronic conditions in US children and is one of the top unmet health care needs of poor children across the country. If left untreated, ECC has broad dental, medical, social, and quality of life consequences.4

EPIDEMIOLOGY

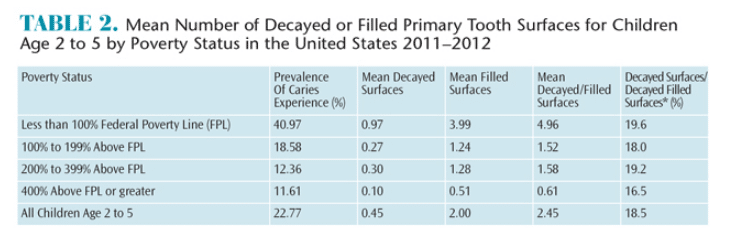

The most recent data on the prevalence of ECC in the US are derived from the 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.5 Although NIDCR sponsored the oral health examination component within NHANES, the definition of ECC that was used in this data collection differs from the operational case definition for ECC that emerged from NIDCR’s 1999 conference.2 In the NHANES caries criteria, the “decayed” component includes only cavitated lesions, excluding the noncavitated lesions that are part of the case definition of ECC from the earlier NIDCR conference.2 With that in mind, an unpublished analysis of NHANES data for 2011–2012 estimated that 22.8% of US children age 2 to 5 had one or more decayed, missing (due to caries), or restored primary teeth (Table 2).

The prevalence of caries experience varied widely by socioeconomic status, with children living below the federal poverty level (FPL) experiencing nearly four times greater prevalence (41.0%) compared with the prevalence of children from households at or above 400% of the FPL (11.6%). Similarly, the average number of decayed or filled primary tooth surfaces among 2- to 5-year-olds followed a gradient that inversely paralleled socioeconomic circumstances. The score ranged from 4.96 among children living below the FPL to 0.61 among those living at or above 400% of the FPL.

One measure of unmet dental treatment for young children is the proportion of caries that has yet to be treated. This is estimated by the number of decayed surfaces as a fraction of decayed, filled surfaces among those who experienced dental caries. Overall, 18.5% of decayed, filled surfaces in US children age 2 to 5 in 2011–2012 were composed of decayed surfaces (Table 2). This proportion did not differ considerably by family poverty status, and was only slightly lower for those living at or above 400% of the FPL (16.5%) vs those living at less than 100% of the FPL (19.6%).5

EVIDENCE-BASED RECOMMENDATIONS

Despite the longstanding high prevalence of ECC and numerous studies on a wide range of preventive approaches, there are surprisingly few interventions with high-quality evidence supporting their success in prevention. A recently convened conference on ECC prevention and management6 presented findings from a number of commissioned systematic reviews. These reviews found there was insufficient evidence that antimicrobial interventions, such as chlorhexidine or povidone iodine, produce sustained beneficial effects on cariogenic microbiota or were effective in preventing or reducing ECC.7 In addition, there was insufficient evidence supporting the use of silver diamine fluoride, xylitol, chlorhexidine varnish/gel, povidone iodine, probiotic bacteria, or remineralizing agents to prevent or control ECC.8 However, a recently published systematic review of randomized controlled trials of SDF found that it was highly effective at arresting caries in children.9 There was also insufficient high-quality evidence to support the use of sealants, temporary restorations, and traditional restorative care to reduce the incidence of ECC.8 Motivational interviewing has shown some promise in changing parents’ behaviors regarding oral hygiene and feeding, though there is little evidence of its efficacy in preventing or reducing ECC.10

Fluoride varnish is one of few interventions with quality evidence supporting its effectiveness in preventing ECC.8 This is why the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians apply fluoride varnish to the primary teeth of all infants and children starting at the age of primary tooth eruption11 and the American Dental Association recommends fluoride varnish application for children younger than 6 who are at risk for caries.12

Two recent systematic reviews also concluded that the use of standard (1,000 ppm to 1,500 ppm) fluoride toothpaste reduces caries risk in the primary dentition among children at high risk for caries.13,14 In summary, the best available evidence supports the use of at-home daily application and professionally applied forms of topical fluoride to prevent ECC.

The available evidence regarding effective measures to reduce the risk for ECC is reflected in clinical guidelines on caries risk assessment and management from the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (Table 3).15,16 Examples of caries management protocols contained in those guidelines suggest twice-daily brushing with a fluoride toothpaste for 1- to 2-year-old children at moderate or high risk for caries and the use of fluoride toothpaste for children age 3 to 5. In these risk-based protocols, topical fluoride is professionally applied every 6 months for many children or every 3 months for children at moderate or high caries risk.

Modern approaches to ECC prevention and management recommend establishing a dental home by the child’s first birthday, along with anticipatory guidance and caries risk assessment.17 Consequently, access to dental services by young children at risk for ECC is a critical factor in timely and appropriate disease prevention and control. In light of the epidemiology of ECC reviewed above, children living in low-income households are, on average, at elevated risk for disease compared with their more affluent counterparts. Therefore, programs that increase accessibility of dental services for those children should, in theory, lead to improved prevention and control of ECC in a segment of the population at elevated risk for disease.

PUBLIC PROGRAMS

Medicaid is a public program funded jointly by states and the federal government that provides health care coverage primarily for low-income Americans, including eligible children.18 Medicaid is administered by states, according to federal requirements. Under federal requirements, all children enrolled in Medicaid programs are entitled to a comprehensive set of health care services known as early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment (EPSDT). EPSDT includes all medically necessary services, including dental care. Coverage is required up to age 19 in all states, and some states provide coverage up to age 21. Each state also offers coverage under the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which provides low-cost health care coverage for children in families whose incomes are too high to qualify for Medicaid. CHIPRA of 2009 provided states with new funding, additional program options, and a range of new incentives for covering children through Medicaid and CHIP.19

The ACA of 2010 impacted Medicaid coverage—most notably by expanding coverage to adults up to at least 133% of the FPL.20 The ACA also increased Medicaid enrollment of children, primarily through modernizing and simplifying the enrollment process and increasing outreach efforts.21 As of January 2016, 48 states cover children with incomes at or above 200% FPL, with 19 states extending eligibility to at least 300% FPL.22 Medicaid and CHIP currently provide health care coverage to more than 43 million children.23

With the expansion of Medicaid and CHIP coverage, the percentage of uninsured children in the US is declining, from 13.9% in 1997 to 4.5% in 2015.24 This reduction in the percentage of uninsured children is almost entirely due to expanded public coverage. Private coverage for children generally declined during the same period.

IMPACT ON ORAL HEALTH

Based on data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) conducted by the Agency for Health Research and Quality,25 the percentage of children age 2 to 18 who saw a dentist in the preceding 12 months increased from 42.2% in 2000 to 48.3% in 2013. In fact, children’s use of dental services in 2013 was the highest level of utilization recorded since MEPS began tracking it in 1996.26 The increase in utilization was most pronounced among children living below 100% of FPL—from 26.5% in 2000 to 39.0% in 2013—and children at 100% to 200% FPL, from 31.4% to 44.0% during the same period. Use of dental services by Medicaid-enrolled children increased in nearly every state between 2005 and 2013, and the gap in dental care utilization between Medicaid-insured children and privately-insured children has been narrowing.27 Disparities among the states remain, with the prevalence of past-year dental visits by Medicaid-enrolled children in 2013 ranging from 27.9% (Wisconsin) to 64.3% (Connecticut).

An indirect approach to assessing the impact of Medicaid and CHIP expansion on children’s oral health status is to examine recent national trends in caries among children living at or below 200% FPL. Based on data from NHANES, mean decayed filled surfaces for children age 2 to 5 living below 200% FPL declined slightly from 4.0 in 1999 to 2004 to 3.3 in 2011/2012, while mean decayed, filled surfaces among children living at or above 200% FPL remained unchanged at about 1.0.28 However, the composition of decayed, filled surfaces changed dramatically during that interval. The proportion of decayed or filled primary surfaces comprised of filled surfaces increased from about 50% in 1999 to 2004 to about 80% in 2011 to 2012 among children at less than 200% FPL. Children living at or above 200% FPL also experienced a comparable increase in the proportion of caries experience that was treated despite a lower prevalence of disease.

CONCLUSION

The available evidence indicates that the expansion of Medicaid and CHIP, which followed CHIPRA and ACA legislation, was associated with a reduced proportion of uninsured children in the US. The additional coverage provided by these public programs increased the use of dental care services by children living below 200% of the FPL and narrowed the gap between privately and publicly insured children in the use of dental care. However, the range of utilization by Medicaid-enrolled children among the states remains wide. Caries experience among children living below 200% FPL declined slightly during the past decade, suggesting a possible preventive effect associated with increased use of dental services, despite a marked decrease in the proportion of caries experience that went untreated. ECC incidence remains high among children living below or near the FPL. Overall, the pattern of disease suggests that approaches other than increased access to dental services are needed to more effectively prevent ECC. Such strategies may include the delivery of educational services such as motivational interviewing to parents/caregivers, and the application of fluoride varnish on infants and toddlers in nondental settings such as pediatricians’ offices, Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) centers, or other community-based settings.

References

- Loesche WJ. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:353–380.

- Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, Maertens MP, Rozier RG, Selwitz RH. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. A report of a workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Health Care Financing Administration. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:192–197.

- Fontana M. The clinical, environmental, and behavioral factors that foster early childhood caries: evidence for caries risk assessment. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:217–225.

- Casamassimo PS, Thikkurissy S, Edelstein BL, Maiorini E. Beyond the dmft: the human and economic cost of early childhood caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:650–657.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) oral health examination manual, 2011–2012. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/Oral_Health_Examiners_Manual.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- Tinanoff N. Introduction to the conference: innovations in the prevention and management of early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:198–199.

- Li Y, Tanner A. Effect of antimicrobial interventions on the oral microbiota associated with early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:226–244.

- Twetman S, Dhar V. Evidence of effectiveness of current therapies to prevent and treat early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:246–253.

- Gao SS, Zhao IS, Hiraishi N, et al. Clinical trials of silver diamine fluoride in arresting caries among children: a systematic review. JDR Clinical & Translational Research. August 15, 2016. Epub ahead of print.

- Borrelli B, Tooley EM, Scott-Sheldon LA. Motivational interviewing for parent-child health interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:254–265.

- Chou R, Cantor A, Zakher B, Mitchell JP, Pappas M. Preventing dental caries in children <5 years: systematic review updating USPSTF recommendation. Pediatrics. 2013;132:332–350.

- Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT, et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1279–1291.

- Wright JT, Hanson N, Ristic H, Whall CW, Estrich CG, Zentz RR. Fluoride toothpaste efficacy and safety in children younger than 6 years: a systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:182–189.

- Santos AP, Oliveira BH, Nadanovsky P. Effects of low and standard fluoride toothpastes on caries and fluorosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2013;47:382–90.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:132–139.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): unique challenges and treatment options. Pediatr Dent. 2005-2006;27(7 Suppl):34–35.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on dental home. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:24–25.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicaid: Overview. Available at: medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-and-chip-program-information.html. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. State Adoption of Coverage and Enrollment Options in the Children’s Health Insurance Reauthorization Act of 2009. Menlo Park, California: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Affordable Care Act: Eligibility. Available at: medicaid. gov/affordablecareact/provisions/eligibility.html. Accessed May 9, 2016

- Wachino V, Artiga S, Rudowitz R. How Is the ACA impacting Medicaid Enrollment? Menlo Park, California: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014.

- Brooks T, Miskell S, Artiga S, Cornachione E, Gates A. Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-sSharing Policies as of January 2016: Findings From a 50-State Survey. Menlo Park, California: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2016.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid, by Population: Children. Available at: medicaid. gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-population/children/children.html. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- Martinez ME, Cohen RA, Zammitti EP. Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January—September 2015. Hyattsville, Maryland: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2016.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Available at: meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- Nasseh K, Vujicic M. Dental care utilization rate continues to increase among children, holds steady among working-age adults and the elderly. Health Policy Institute Research Brief. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2015.

- Vujicic M, Nasseh K. Gap in dental care utilization between Medicaid and privately insured children narrows, remains large for adults. Health Policy Institute Research Brief. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2015.

- Dye BA, Hsu KL, Afful J. Prevalence and measurement of dental caries in young children. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:200–216.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2016;14(06):56–59.