ROBERTPRZYBYSZ / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

ROBERTPRZYBYSZ / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

Improving Oral Health With School-Based Sealant Programs

Such programs can reduce the risk of dental caries, while improving school attendance and decreasing Medicaid costs.

This course was published in the June 2016 issue and expires June 30, 2019. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Briefly discuss the effectiveness of sealants in caries prevention.

- Define school-based sealant programs (SBSPs) and their success in reducing the incidence of caries.

- Identify challenges to implementing SBSPs and strategies for overcoming them.

DEFINING SCHOOL-BASED SEALANT PROGRAMS

The implementation of SBSPs requires the use of portable dental equipment, a mobile van/bus with dental equipment, or fixed dental equipment that is installed in a school as part of a larger school-based health center. The use of portable dental equipment provides the greatest flexibility and is the most cost-efficient.10 SBSPs often use the federally funded free and reduced meal program participation rates to identify high-risk schools/groups of children. This percentage appears to correlate with a school’s cohort of children who are eligible for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. This population is less likely to have access to regular dental services and has a higher incidence of caries.11

EFFECTIVENESS OF SCHOOL-BASED SEALANT PROGRAMS

Strong evidence supports the delivery of dental sealants via SBSPs.9 The implementation of such programs has contributed to a 26% increase in the number of children who receive sealants.9 This percentage is higher among children from low-income families.9

The cost to place sealants on a child in a SBSP is approximately $100 compared with the lifetime cost to maintain a tooth that develops caries, which can exceed $2,000.12,13 Students with access to school-based preventive dental services like sealants are less likely to miss school because of caries.9 A child receiving school-based preventive dental services typically misses 20 minutes to 30 minutes of class time compared with an hour or more if he or she leaves the school for a dental appointment. However, school-based care is not meant to replace a dental home. Rather, these programs provide alternative routes into dental homes and the oral health care system as a whole. As such, delivering dental sealants in school-based settings can reduce student absenteeism, decrease Medicaid expenditures, and save both money and time for parents/caregivers.14

CHALLENGES, BARRIERS, AND SOLUTIONS

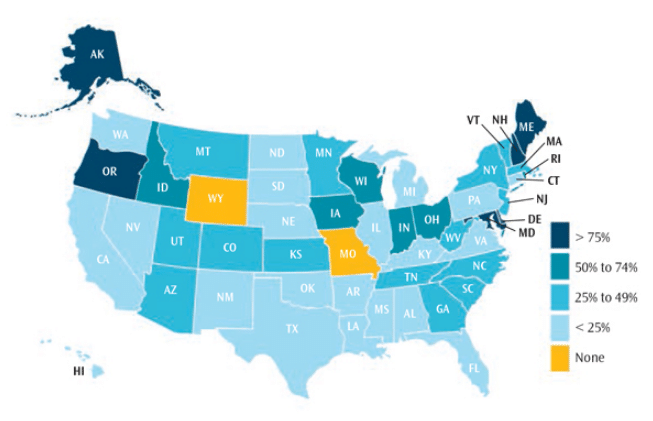

Even with strong evidence supporting dental sealant placement in school-based settings, sealants are still underutilized across the country (Figure 1). Currently, only 11 states have SBSPs in more than half of their high-risk schools.2 A study conducted between 2011 and 2012 found only four out of 10 children age 6 to 19 had one or more sealants.2 Barriers and challenges to implementing SBSPs include restrictive state dental practice acts, financial sustainability, acceptance from school staff/administration, and inertia—all of which hinder wider implementation of evidence-based SBSPs.

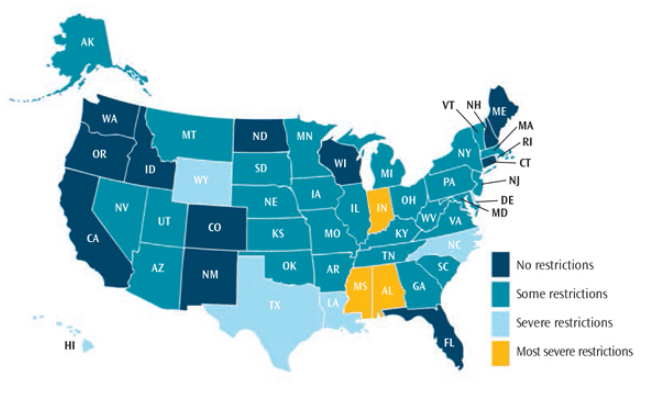

Despite the barriers to widespread adoption of SBSPs, steps can be taken to improve implementation. Restrictive state dental practice acts serve as barriers to providing school-based care and limit access to preventive dental services (Figure 2).3 Allowing dental hygienists to place sealants without a prior exam by a dentist can increase access to care and lower program costs by 18% to 29%, depending on the program size.2 Currently, 10 states—Alabama, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Texas, and Wyoming—and the District of Columbia require a prior exam by a dentist before sealants can be placed. Alabama, Mississippi, Indiana, and the District of Columbia require a dentist to be present when a sealant is applied in a school-based program.2 More high-risk schools are served by SBSPs in states that allow dental hygienists to apply sealants without patients first needing to receive dentist-performed exams.2

Some states allow dental hygienists to operate under special credentialing, such as Arizona’s affiliated practice dental hygienist. Arizona dental hygienists who meet specific continuing education-based credentialing standards are permitted to provide dental hygiene services (without prior exams by dentists) and receive direct reimbursement from the state’s Medicaid system. Since 1989, Wisconsin has permitted dental hygienists without additional credentialing to provide dental hygiene services in schools without prior exams by dentists. No dental hygienists have been subjected to disciplinary action related to care rendered in SBSPs since the practice act changed more than 25 years ago. Dental hygienists working in SBSPs who establish strong relationships with dentists can provide referrals for children who need additional care.

Dental hygienists are trained to provide the necessary services provided in SBSPs by virtue of graduating from a dental hygiene program accredited by the Commission on Dental Accreditation and attaining state licensure as dental hygienists.15 States looking to increase the utilization of SBSPs need to permit dental hygienists to assess and seal teeth without requiring that children receive a prior exam from a dentist. Removing this barrier alone has the potential to increase the number of high-risk children who receive this important evidence-based preventive treatment. Intervention costs are lower when dental hygienists rather than dentists are used to determine whether sealants are appropriate.9 Furthermore, by 2025, all 50 states and the District of Columbia are predicted to experience a shortage of dentists, and 45 states will most likely have a surplus of dental hygienists.16 Exploring innovative methods to better utilize dental hygienists to provide the care they are trained for and competent to provide may make the difference in efforts to reduce the prevalence of dental disease.

Allowing dental hygienists to be reimbursed directly from state Medicaid agencies is another way states can increase SBSPs. Currently, 17 states allow direct Medicaid reimbursement to dental hygienists.17 In Wisconsin, the numbers of SBSPs increased dramatically after 2006, when Medicaid began directly reimbursing dental hygienists for preventive services. State expenditures and funding from Delta Dental of Wisconsin for SBSPs also grew in 2007.12 Between 2002 and 2012, Wisconsin increased the number of SBSPs tenfold, during which time the percentage of third graders with untreated caries fell from 31% to 18%.18 During the same period, the percentage of third graders with sealants increased from 47% to 61%.18 Furthermore, Wisconsin SBSPs increased the number of high-risk children who received dental sealants. Between 2008 and 2012, the percentage of children in schools with the highest free and reduced meal program participation rates increased in sealant prevalence from 34% to 60%.18

Another barrier to providing school-based care is gaining acceptance from school faculties and support staff. Education professionals need a clear understanding of their roles in SBSPs, the space required, and the resultant time and scheduling needs. Developing strong relationships with school nurses, teachers, and administrators can support the success of SBSPs. The school administration needs to view a SBSP as an additional benefit for students. Discussing the positive health outcomes of preventive dental care, scientific evidence supporting sealants, and the ability of SBSPs to reduce absenteeism are key to ensuring schools buy into the need for such programs.

To successfully reduce the incidence of caries, clinicians must use proper techniques and follow evidence-based guidelines for sealant placement. In 2008 and 2009, respectively, the American Dental Association (ADA) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published recommendations regarding sealant placement.14,15 The panel convened by the CDC looked specifically at recommendations pertaining to SBSPs.19 Both the ADA and the CDC recommended visual inspection (not the use of an explorer) as the preferred method to determine if a sealant should be placed.19,20 Both organizations’ recommendations suggested placing sealants to stop the progression of noncavitated pit-and-fissure lesions, provided guidance on appropriate tooth preparation techniques, and provided guidance on sealant materials. The ADA has recently convened another expert panel to conduct an updated systematic review and provide clinical guidelines on sealant placement. The panel’s findings will be released in fall 2016. Additionally, the Children’s Dental Health Project has convened a group of SBSP experts who will release recommendations and tools to improve SBSP outcomes and efficiencies in late 2016.21

Another issue to consider when implementing SBSPs is the need for appropriate infection control measures in a mobile/portable dental setting. The Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention has site assessment checklists and a variety of other resources to help guide SBSPs in addressing the unique aspects of ensuring strong infection control practices in mobile and portable settings.22 An additional resource is the manual Seal America: The Prevention Invention by Nancy Carter, RDH, MPH, which provides guidance on the initial development and implementation of SBSPs.10

Before sealants can be placed, informed consent from all participants’ parents/caregivers must be obtained. This can be challenging. Parents/caregivers need to be educated about sealants, the importance of prevention, and risks and benefits of care. This educational effort is typically accomplished via information sent home with students rather than face-to-face. Attending back-to-school fairs, inserting sealant program consent forms into back-to-school registration packets, and providing education to parents in classrooms at the beginning of the school year can improve consent rates.

An additional way to improve consent-form return rates is the use of incentives for students, teachers, and schools. A pilot project during the 2015 school year in Wisconsin showed improvements by incentivizing students. In the first year of offering incentives to students, more than 5,000 additional children returned consent forms. Incentives include a refillable water bottle, small backpack, toothbrush, and dentifrice. Teachers and schools are also provided incentives when their classrooms or schools reach a predetermined number of returned consent forms. Gift cards can be used as incentives for teachers, while schools may be motivated by the possibility of new physical education equipment. Efforts like these have led to more than 2,200 additional children receiving preventive services in a Wisconsin-based pilot project.

CONCLUSION

The effectiveness of SBSPs in reducing caries incidence is clear.9 SBSPs have been shown to be valuable, effective, and efficient programs that address key oral health needs of children.9 In addition to supporting oral health, SBSPs can help improve school attendance, reduce costs to state Medicaid programs, and provide other benefits, such as preventing pain-based impairments to school performance and saving money and time for parents/caregivers.9,14 Addressing the challenges and overcoming barriers that SBSPs encounter are worthwhile endeavors that can lead to reductions in caries incidence.

References

- Downey M. Chronic absenteeism: Why do so many kids miss so much school and what can be done? Available at: getschooled.blog.myajc.com/ 2015/08/26/chronic-absenteeism-why-do-so-many-kids-miss-so-much-school-and-what-can-be-done. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts. States Stalled on Dental Sealant Programs. Available at: pewtrusts.org/en/ researchandanalysis/reports/2015/04/states-stalled-on-dental-sealant-programs. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Hagel N, Vannah D. Seal away caries risk. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2015;13(6):3‐36.

- Godhane A, Ukey A, Tote JV, et al. Use of pit and fissure sealant in prevention of dental caries in pediatric dentistry and recent advancement: a review. Int J Dent Med Res. 2015;1:220.

- Avinash JMC, Dhingra S, Gupta P, Kataria S, Meenu, Bhatia HP. Pit and fissure sealants: an unused caries prevention tool. J Oral Health Com. 2010;4:1‐6.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Seal Out Tooth Decay. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/oralhealth/Topics/ToothDecay/SealOutToothDecay.htm#howLongDo. Accessed May 1, 2016.

- Griffin SO, Oong E, Kohn W, et al. The effectiveness of sealants in managing caries lesions. J Dent Res. 2008;87:169‐174.

- Guide to Community Preventive Services. Preventing Dental Caries: School-Based Dental Sealant Delivery Programs. Available at: thecommunityguide. org/oral/schoolsealants.html. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Carter N. Seal America: the prevention invention. Available at: mchoralhealth.org/seal. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Bouchery E. Utilization of dental services among Medicaid-enrolled children. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review. 2013;3:E1-E16.

- Children’s Health Alliance of Wisconsin. Partnering to Seal-A-Smile: A Report on the Success of School-Based Programs in Wisconsin. Available at: chawisconsin.org/documents/PartneringSealASmile2012.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Delta Dental. The True Cost of a Cavity. Available at: deltadentalins.com/about/community/cavity-cost.html. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Tooth Decay. Available at: cdc.gov/ policy/hst/statestrategies/oralhealth/index.html. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs. Available at: ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/ dh.ashx. Accessed Mary 2, 2016.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National and State-Level Projections of Dentists and Dental Hygienists in the US, 2012-2025. Available at:?bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/dentistry/nationalstatelevelprojectionsdentists.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Advocacy: Reimbursement. Available: adha.org/reimbursement. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Division of Public Health. Healthy Smiles Healthy Growth: Wisconsin’s Third Grade Children. Available at: dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p0/p00589.pdf. Accessed Mary 2, 2016.

- Gooch BF, Griffin SO, Kolavic GS, et al. Preventing dental caries through school-based sealant programs: Updated recommendations and reviews of evidence. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1356‐1365.

- Beauchamp J, Saufield PW, Crall, JJ, et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations for the use of pit-and-fissure sealants. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:257‐268.

- Children’s Dental Health Project. Teeth Matter: Sealant Work Group Begins its Crucial Work. Available at: cdhp.org/blog/380-sealant-work-group-begins-its-crucial-work. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention. Portable/Mobile Infection Control Overview. Available at: osap.org/?page=PortableMobile. Accessed May 2, 2016.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2016;14(06):52–55.