LENBLR / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

LENBLR / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

The Radiology Chain of Asepsis

Maintaining appropriate infection control protocol protects both patients and clinicians.

When exposing radiographs in a clinical setting, the chain of asepsis must not be broken. Diminishing possible routes of disease transmission, avoiding cross-contamination, and following the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations are key to establishing a safe work environment. Although much focus has been placed on reducing the risks posed by aerosols in the dental setting due to the pandemic, infection control protocols for intraoral and extraoral radiology should not be neglected.

Despite the fact that radiology does not emit aerosols nor typically induce bleeding, it still poses the possibility of exposure to potentially infectious diseases. Saliva contains high counts of bacteria, fungi, and viruses.1 Virulent pathogens, the ability of microorganisms to survive on surfaces for extended periods, and susceptibility of the host all impact cross-contamination risk.

Clinicians may be exposed to bloodborne pathogens if the radiology chain of asepsis is broken. Blood exposures may occur in the floor of the mouth due to the placement of digital, traditional, or photostimulable phosphor (PSP) plates. Among patients who have recently undergone oral surgery, blood is frequently present in their saliva. Furthermore, protective covers or barriers should be used in addition to disinfection procedures following completion of patient treatment.

The first step in planning a radiology infection control protocol is to review the scheduled procedure prior to the start of the appointment. Then oral health professionals are prepared for what supplies and equipment will be needed and how each is to be disposed of, disinfected, or sterilized.2 Disposable supplies include cotton rolls, bitewing tabs, and plastic barriers. Items that need to be disinfected or barrier protected are countertops, patient chair, tube head and arms, control panel, light switch, and any other areas touched while exposing radiographs. When setting up the operatory and before the patient’s arrival, all clinicians must perform appropriate hand hygiene.

Taking radiographs, especially a full-mouth radiographic series, does pose a risk of cross-contamination between patient and operator. Care must be taken to separate items that are considered clean or unexposed from those that are dirty or exposed.

Processing images from traditional film and PSPs occurs in the darkroom or scanning room. Before receptors are processed, the receptor barrier covering must be disinfected. Oral health professionals should enter the processing/scanning area with clean hands and appropriate hand hygiene is imperative throughout the procedure. Clinicians should also don new gloves after using hand sanitizer when loading exposed receptors. After all receptors are scanned and images are mounted, new gloves are donned. All areas touched should be disinfected by removing visible debris, followed by disinfecting agents according to the manufacturer’s instructions for use.

After the patient is dismissed, the closing of the aseptic chain can begin. With gloved hands, the provider should discard all disposable items in the proper receptacle. Positioning devices should be taken to the sterilization lab to be sterilized; all positioning devices should be heat sterilized. Before continuing with disinfection of the operatory, the provider should remove contaminated gloves, perform hand hygiene, and then clean and disinfect clinical contact surfaces.

Proper Receptor Cleaning

Although digital radiography has many benefits compared to film, it also creates new infection control challenges. According to the CDC, digital sensors are semi-critical items because they come into contact with mucous membranes. Therefore, digital sensors should ideally be heat-sterilized or cleaned with a high-level disinfectant between patients.3

PSP receptors cannot be sterilized by heat or most chemical disinfectants due to their design. Similarly, direct digital sensors cannot be sterilized using heat or ethylene oxide for the same reason. If digital sensors cannot tolerate these procedures, the CDC recommends they be protected with a US Food and Drug Administration-cleared barrier in addition to cleaned and disinfected with an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered intermediate-level (tuberculocidal claim) hospital disinfectant. The main difference between sterilization and the use of an intermediate-level disinfectant is that sterilization is the total destruction of all pathogens along with most bacterial spores by heat (eg, autoclave, dry heat, unsaturated chemical vapor) or liquid chemical sterilant. An intermediate-level disinfectant is a hospital-level disinfectant with tuberculocidal ability that can destroy most pathogens and other microorganisms physically or chemically.3,4

Chen et al5 and Kalathingal et al6 showed that ethylene oxide is an effective sterilization method to sterilize PSP receptors without damaging them. Ethylene oxide gas, however, is not environmentally friendly and most dental offices don’t have access to it.5,6 In addition, quaternary ammonia and alcohol-based, phenol-based, and hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectant wipes can effectively kill oral bacteria and inhibit spore outgrowth; hence, they are effective ways to disinfect contaminated PSP barrier bags (also referred to as packets or envelopes) and direct digital sensors.5,7 Manufacturers of these sensors/receptors should be contacted when selecting a proper disinfectant. In addition, review the manufacturer’s instructions for cleaning and disinfecting their products before reusing them on patients.

If a direct digital sensor is used, the clean sensor holder should be covered with a plastic barrier and a clean plastic disposable sensor sleeve inserted on the digital sensor. This plastic barrier should tightly fit the sensor and extend a few inches along the sensor cord.8,9 These barriers are subject to perforations.

A two-step process of cleaning and disinfecting sensors must be followed to achieve proper disinfection between patients. The cleaning step is to remove debris and organic matter (eg, saliva, blood, and other contamination), which can shield microorganisms from being properly disinfected. Therefore, the sensor, cord, and sensor holder must first be cleaned with an EPA-registered intermediate-level hospital disinfectant wipe or suitable cleaning agent if the disinfectant wipe does not contain a cleaning agent. Failure to complete this step could compromise the disinfecting process.

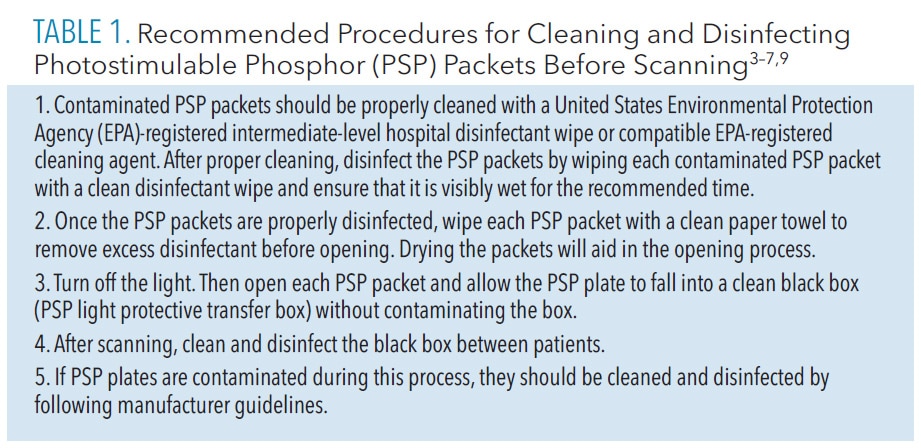

For the disinfection step, all surfaces must be wiped again with a clean disinfectant wipe and must be visibly wet for the time recommended by the disinfectant product.3,5,7 Direct digital sensors vary by company, so the sensor manufacturer should be contacted to ensure that it can tolerate these disinfectants.3–5 Table 1 lists the recommended procedures for cleaning and disinfecting PSP packets before scanning.3–7,9

Personal Protective Equipment

Maintaining proper infection control and using personal protective equipment (PPE) during radiology procedures are integral to preventing cross-contamination. The CDC states that hand hygiene is the most important measure to prevent the spread of infection in dental settings.3 Making sure soiled gloves are removed, proper infection control procedures are followed before entering scanning room locations, and appropriate handling of PSP or digital sensors (in which barriers have been removed) can prevent contamination on surfaces.

Masks, face shields, and gowns should be worn during exposure and handling of radiology devices and will help shield and protect oral health professionals from airborne droplets. Villani et al10 found that N95 respirators provide better protection against viral respiratory infections than surgical masks.10 Surgical masks block particles, such as droplets, but their efficacy can be compromised due to poor fit.11 Face shields provide another layer of protection; they should not be worn alone but rather used as an adjunct to reduce respiratory infections.12,13

Radiation protective garments, such as lead aprons and thyroid collars, protect patients from additional radiation exposure. They are reused multiple times during the day, thus require proper disinfection. Lead aprons and thyroid collars come in many designs. For example, some have wipeable layers on the inner and outer surface, while others have outer wipeable layers and inner fabric layers. These surfaces can be cleaned with an intermediate-level disinfectant. The inner fabric covering of a lead apron or thyroid collar that lies against the patient can be soiled. As such, these radiation protective garments may need to be replaced every 18 months to 24 months. However, fabric covering can be spot cleaned with mild soap and scrub brush.14

Conclusion

Developing and adopting a radiographic infection control policy is critical in preventing cross-contamination and maintaining a safe dental environment for patients, staff members, and dental providers. Bacterial and viral infections, such as Legionnaires disease, tuberculosis, and hepatitis, can be prevented by the implementation of specific infection control protocols.15 These protocols are useful in aerosol and nonaerosol producing dental procedures, such as exposing radiographs.

References

- Gumru, B, Tarcin, B, Idman E. Cross contamination and infection control in intraoral digital imaging: a comprehensive review. Oral Radiol. 2020;37:180–188.

- Miles D, Van Dis M, Williamson G, Jenson C. Radiographic Imaging for the Dental Team. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care. Available at: cdc.g/v/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/pdf/safe-care2.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2022.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental health care settings—2003J J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:33–47.

- Chen L, Mauriello SM, Arnold R. Surface disinfection of PSP barriers with H2O2 vs phenol wipes. J Dent Res. 2018;97:117.

- Kalathingal S, Youngpeter A, Minton J, et al. An evaluation of microbiologic contamination on a phosphor plate system: is weekly gas sterilization enough? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:457–462.

- Chen L, Mauriello SM, Platin E, Arnold R. Comparison of sporicidal activities of disinfectant wipes for surface decontamination. Available at: core.ac.uk/download/pdf/㳂.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2023.

- Choi JW. Perforation rate of intraoral barriers for direct digital radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2015;44:20140245.

- Mallya SM, Lew N. White and Pharoah’s Oral Radiology: Principles and Interpretation. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2019.

- Villani FA, Aiuto R, Paglia L, Re D. COVID-19 and dentistry: prevention in dental practice, a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4609.

- Lo Giudice R. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2) in dentistry. management of biological risk in dental practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3067.

- Ray M, Freudenthal J. The ABC’s of face shields. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2022;20(1)14–17.

- Li DTS, Samaranayake LP, Leung YY, Neelakantan P. Facial protection in the era of COVID-19: a narrative review. Oral Dis. 2021;27(Suppl 3):665–673.

- Honigsberg H, Speroni KG, Fishback A, Stafford A. Health care workers’ use and cleaning of x-ray aprons and thyroid shields. AORN J. 2017;106:534–546.

- Malsam R, Nienhaus A. Occupational infections among dental health workers in Germany—14-year time trends. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:10128.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November/December 2022;20(11)12,14-15.