LIGHTFIELDSTUDIOS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

LIGHTFIELDSTUDIOS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Protecting Public Health

In light of declining vaccination rates, oral health professionals need to be knowledgeable about current vaccine recommendations so they can best advise their patients and support public health.

PART 2 of a two-part series The first installment provided an overview of vaccine recommendations and appeared in the July 2018 issue.

Oral health professionals are exposed to infectious agents that can be transmitted to and from clinicians and patients. Fortunately, there are myriad strategies to maintain a safe environment—from effective surface disinfection to donning personal protective equipment. Vaccinations are another essential component to maintaining health for both clinicians and the public at large. Unfortunately, the United States is experiencing a downturn in compliance with vaccination recommendations, putting public health at risk.

TROUBLING TREND

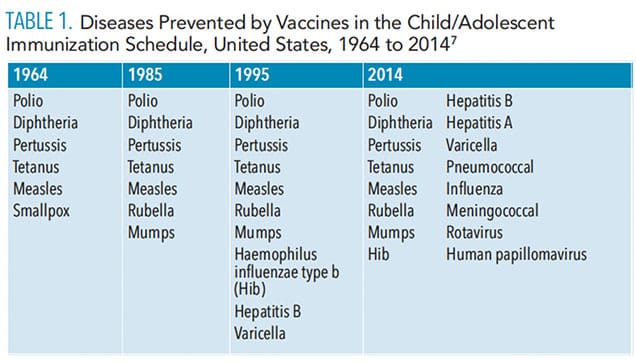

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), a federal advisory committee that provides expert advice to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services on the use of vaccines in the US, was created in 1964. Since its inception, the number of vaccines included in the recommended child/adolescent immunization schedule has increased from vaccines targeting six diseases to the prevention of 16 diseases (Table 1).1 The recommended immunization schedule for adults includes vaccines targeting 15 vaccine-preventable diseases.1

Despite the long history of vaccine benefits, in 2018, the CDC identified a trend in which an increasing number of children (kindergarten and younger) are not receiving the required vaccinations.2 This is concerning as not only do vaccinations keep children healthy, but they also protect others who are at increased risk for developing disease-related complications. If individuals with compromised immune systems, children who are too young to be vaccinated, organ transplant recipients, and people with cancer come into contact with a child who is contagious, long-term medical complications and/or death could result.3 The rates of some of the more contagious vaccine-preventable diseases are higher in other countries and can be brought to the US by international travelers, increasing an unvaccinated child’s risk for contracting an illness. Many of the vaccine-preventable diseases carry serious complications for children such a hearing loss, paralysis, brain damage, and death.3

MEASLES PANDEMIC

Measles was declared eliminated from the US in 2000 thanks to a highly effective vaccination program, as well as improved measles control in the greater Americas region.4 However, measles has resurged in communities with low vaccination rates due to the influence of anti-vaccination activists and an increasing number of parents who refuse to vaccinate their children.

The CDC announced a “global measles outbreak” on February 24, 2019, due to the fact that Africa, the Americas, Europe, and the Western Pacific are experiencing large, often extended outbreaks of the disease.5 The majority of US measles cases originated from unvaccinated American residents returning from international travel destinations with large outbreaks.6

A total of 981 individual measles cases were reported across 26 states in June 2019.7 Most occurred in New York, Michigan, and Washington State. The disease spread among unvaccinated people in Orthodox Jewish communities in New York State (Rockland County), New York City (Brooklyn), and New Jersey after travelers brought measles back from Israel, which had an outbreak of its own. The disease then was carried to Michigan. A large outbreak in southern Washington State spread mostly among unvaccinated children younger than 10. And in late April, hundreds of people were put under quarantine at two Los Angeles universities after a reported outbreak.8,9

The CDC has partnered with the World Health Organization, Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations, and Measles and Rubella Initiative to support global health security to reduce the risk of measles transmission. This approach—which includes surveillance and specialized laboratory testing; planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of immunization campaigns; and reviews of immunization programs—can protect Americans from contracting measles from other countries.5

MEASLES PREVENTIVE MEASURES

To protect America’s health, the CDC works with the Department of Homeland Security to prevent the spread of serious contagious diseases during travel. CDC uses a “Do Not Board” list to prevent travelers from boarding commercial airplanes if they are known or suspected to have a contagious disease that poses a threat to public health. Sick travelers are also placed on a “Lookout” list so they will be detected if they attempt to enter the US by land or sea.6,10 Once public health authorities confirm a person is no longer contagious, the individual is removed from the lists (typically within 24 hours). The CDC reviews the records of all individuals on the lists every 2 weeks to determine whether they are eligible for removal.10

To encourage vaccination rates, the US Food and Drug Administration also reassures the public that the measles, mumps, and rubella, or German measles (MMR) vaccine is safe and effective.11 Messages regarding the safety and effectiveness of the MMR vaccine are posted in different languages via social media in ethnic communities to reach as many residents as possible. Though there are no US federal vaccination laws, all 50 states have regulations requiring children attending public school to be vaccinated against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (generally in a DTaP vaccine); polio (an IPV vaccine); measles and rubella (generally in a MMR vaccine); and varicella (chickenpox). All 50 states allow medical exemptions, 47 states allow religious exemptions, and 17 states allow philosophical (or personal belief) exemptions.12 Each state has enacted laws on vaccination regulations and exemptions that are subject to change.

MEASLES OUTBREAK IN NEW YORK

Officials in Rockland County, New York, issued an emergency order on April 16, 2019, banning anyone diagnosed with measles or exposed to measles from gathering in public places including schools, restaurants, and places of worship for up to 21 days, or face a fine of $2,000 a day.6,13 Since New York experienced the worst measles outbreak in decades, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed a bill on June 13, 2019, that ended vaccination exemptions based on religious beliefs.14 Under the new law, unvaccinated children will not be allowed to go to school; however, parents will still be able to opt out of vaccinations for health reasons, such as weakened immune systems.15

To stop the spread of measles in New York City, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene implemented a public-health policy on April 9, 2019. Adults and children ages 6 months and older who live, work, or go to school in zip codes with the greatest risks of contracting measles are required to get the MMR vaccination within 48 hours. The policy is intended to protect others in the community and help curtail the ongoing outbreak.6,16 Under the mandatory vaccination, members of the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene check the vaccination records of individuals who may have been in contact with infected patients. Those who have not received the MMR vaccine or do not have evidence of immunity may be given a violation and could be fined $1,000.16 Additionally, the officials with the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene warned it would close private schools in these communities if nonvaccinated students attended classes during the current measles outbreak. To comply with this vaccine mandate, some local religious leaders were urging their members to get vaccinated.

WHOOPING COUGH

Whooping cough—a potentially life-threatening childhood illness that disappeared in the 1940s after a vaccine was developed—has made a comeback. Incidences were confirmed in the United Kingdom, California, New Jersey, and Hong Kong from January 2018 to March 2019. Experts said the changes in the vaccine and diminishing immunity are likely contributing to the resurgence of the illness.17–20

Two forms of vaccine are in use, the whole-cell vaccine (wP) and the acellular vaccine (aP). Whole-cell pertussis vaccines were developed first, and are suspensions of the entire B. pertussis organism that has been inactivated, usually with formalin. Most wP vaccines are available in combination with diphtheria (D) and tetanus (T) vaccines. Immunization with wP vaccines is effective and the vaccine is relatively inexpensive, but immunization has been frequently associated with minor adverse reactions, such as redness and swelling at the site of injection, fever, and agitation. To address the adverse reactions observed with the whole-cell vaccines, aP vaccines were developed that contain purified components of B. pertussis, such as inactivated pertussis toxin, either alone or in combination with other B. pertussis components, such as filamentous haemagglutinin, fimbrial antigens, and pertactin.21

The US switched the type of vaccine offered to children from whole cell pertussis (DTwP) to acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccines during the 1990s. Currently, DTaP vaccines are used for all five childhood doses at ages 12 months to 18 months, 2, 4, and 6 for maximum protection. DTaP vaccines help children younger than 7 develop immunity to three deadly diseases caused by the bacteria: diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough (pertussis).22

Despite high levels of vaccine coverage, the US has experienced an increase in whooping cough cases in the years following the switch to the new vaccine. In 2006, a booster acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine was recommended by the ACIP for all adolescents ages 11 to 12.23 Findings from Kaiser Permanente’s 2016 Vaccine Study Center found that among teenagers who have received acellular pertussis vaccine only, Tdap provides moderate protection against pertussis during the first year after vaccination and then protection wanes to < 9% at ≥ 4 years post-vaccination.23 The results of this study raise serious questions regarding the benefits of routinely administering a single dose of Tdap to every adolescent ages 11 to 12. Tdap provides reasonable short-term protection against pertussis, becoming more effective if administered to adolescents in a local pertussis outbreak rather than on a routine basis.23

TETANUS DIPHTHERIA ACELLULAR VACCINE RECOMMENDATIONS

Teens or adults who did not receive Tdap as a preteen should get one dose. Receiving the Tdap is especially important for pregnant women during each pregnancy. They should receive a vaccination in the second or third trimester, preferably before 35 weeks of gestation. By inoculating the mother before giving birth, the vaccine’s protection is passed to the child. It can also be transferred by breastfeeding.20 Individuals who care for babies should also be up-to-date with the pertussis vaccination.22

Individuals can get the Tdap booster regardless of whether they received the previous tetanus and diphtheria booster shot (Td). In addition, individuals should get Tdap vaccine even if they’ve had the pertussis vaccine as a child or have been sick with pertussis in the past.22 Individuals should consult with their physicians to determine their vaccination status and need.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals need to know where to access important information regarding immunization schedules, how vaccine preventable diseases are spread, and where to refer patients. A current understanding of the benefits and risks associated with the vaccinations most commonly administered in the US will assist clinicians in addressing patients’ concerns accurately. Clinicians who travel and practice outside of their local area need to stay informed about what is happening at a community level. For example, if a clinician is practicing in a community where there is a measles outbreak, he or she should be aware of the local health department’s current guidelines and recommendations. The CDC’s website (cdc.gov) is a valuable resource to provide to patients when concerns and/or questions arise regarding infectious diseases. The CDC provides comprehensive information and resources for health care providers to use as well as information for the general public. If a clinician feels a patient’s condition is of immediate concern, a referral should be made to the patient’s health care provider or the local department of health. Vaccine preventable illnesses are still a threat in the US. As clinicians, but more importantly as members of society, we have an obligation to stay updated on current events regarding immunizations so that collectively we can support public health.

REFERENCES

- Smith JC, Hinman AR, Pickering LK. History and evolution of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices United States, 1964-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:955–958.

- Wappes J. More young kids not getting vaccinated. University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. Available at: cidrap.umn.e/u/news-perspective/2018/10/more-young-us-kids-not-getting-vaccinated. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Vaccine Information You Need. Importance of vaccines: top 10 reasons to protect your children through vaccination. Available at: vaccineinformation.org/vaccines-save-lives/. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles history. Available at: cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global measles outbreaks. Available at: cdc.gov/globalhealth/measles/globalmeaslesoutbreaks.htm. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Sun LH. Officials fighting U.S. measles outbreaks threaten to use rare air travel ban. The Washington Post. May 24, 2019.

- Cai W, Lu D, Reinhard S. Largest US measles outbreak in 25 years surpasses 980 cases. New York Times. June 3, 2019.

- Lambert J. Measles cases mount in Pacific Northwest outbreak. Available at: npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/02/08/692665531/measles-cases-mount-in-pacific-northwest-outbreak. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Brice-Saddler M. Hundreds of students and staff from two LA universities remain quarantined amid measles scare. The Washington Post. April 26, 2019.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travel Restrictions to Prevent the Spread of Disease. Available at: cdc.gov/quarantine/travel-restrictions.html. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Mezher M. FDA reassures public that MMR vaccine is safe and effective. Available at: raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2019/4/fda-reassures-public-that-mmr-vaccine-is-safe-and. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- ProCon.org. State Vaccination Exemptions for Children Entering Public Schools. Available at: vaccines.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=003597. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Brum R. Measles: Rockland issues new ‘exclusion order’ for public spaces. Rockland/Westchester Journal News. April 16, 2019.

- New York State. Governor Cuomo Signs Legislation Removing Non-Medical Exemptions from School Vaccination Requirements. Available at: governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-signs-legislation-removing-non-medical-exemptions-school-vaccination. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- CBS New York. Measles Outbreak: New York State Ends Religious Exemptions for Vaccinations. Available at: newyork.cbslocal.com/2019/06/14/new-york-ends-religious-exemptions-for-measles-vaccinations/. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- ABC 7 NY. Measles Outbreak: New York City Orders Mandatory Vaccines for Parts of Brooklyn. Available at: abc7ny.com/health/measles-outbreak-nyc-orders-mandatory-vaccines-for-some/5239006/. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Public Health England. Laboratory Confirmed Cases of Pertussis (England): Annual Report for 2018. Available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachme_t_data/file/797712/hpr1419_prtsss-ann.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Bender M. California keeps close eye on whooping cough after infant’s death. Available at: cnn.com/2018/07/19/health/california-whooping-cough/index.html. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Alexander D. Summit schools on alert after 2 students get whooping cough. Available at: nj1015.com/summit-schools-on-alert-after-2-students-get-whooping-cough/. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Ng KC. Women urged to get whooping cough vaccine during each pregnancy as Hong Kong health authorities release latest recommendations on disease. South China Morning Post. March 4, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Pertussis. Available at: who.int/biologicals/vaccines/pertussis/en/. Accessed December 6, 2019.

- Oliviero H. Why whooping cough is making a comeback. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. September 5, 2018.

- Klein NP, Bartlett J, Fireman B, et al. Waning Tdap effectiveness in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153326.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2020;18(1):22,24–25.