MANIKI_RUS/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

MANIKI_RUS/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

Oral Health Effects of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

A greater knowledge of this disorder will help clinicians successfully provide dental care to this vulnerable population.

This course was published in the February 2022 issue and expires February 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD).

- Identify the prevalence and common physical characteristics of FASD.

- Discuss strategies for providing effective oral healthcare to this patient population.

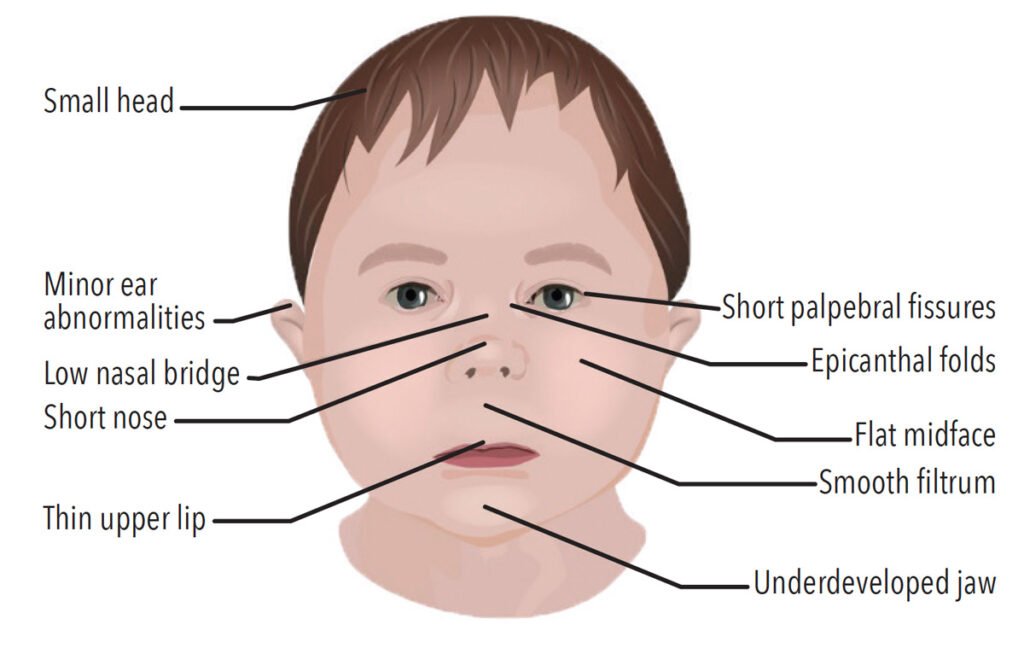

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) is a diagnostic term used to describe a complex neurodevelopmental disorder resulting in permanent and sometimes progressive disabilities caused by prenatal alcohol consumption.1 The teratogenic effects of alcohol on human embryos were first demonstrated in 1968, showing a consistent pattern of birth abnormalities in 127 children born to alcoholic mothers in France.2,3 Microcephaly, ptosis of the top eyelid (epicanthic folds), a short and upturned nose, thin vermillion of upper lip, and retrognathia, an abnormal posterior positioning of the mandible were among the first traits identified. Additionally, the children exhibited developmental delays in both motor and mental functions. Several of the children also presented with congenital heart defects, abnormal skin creases on the palm of the hand, and/or restricted supination—a rotation of the foot. Since then, many studies have confirmed the hallmark facial characteristics of FASD, as well as craniofacial abnormalities, growth impairments, and developmental delays.1 An individual with FASD may have physical, intellectual, or behavioral problems, or a combination of all three.

In the midst of a global pandemic, alcohol consumption has increased significantly.4 Therefore, all healthcare providers should be well-versed about the risk of prenatal alcohol consumption to raise public awareness and to effectively care for patients with FASD. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 3.3 million women between the ages of 15 and 44 are potentially exposing developing fetuses to alcohol because of their alcohol consumption while sexually active without taking birth control.4 Furthermore, three out of four women who wish to become pregnant continue consuming alcohol after discontinuing the use of birth control. It is possible that alcohol intake during pregnancy, particularly in the first few weeks and before a woman discovers she is pregnant, may result in a child having long-term physical, behavioral, and intellectual deficits.4,5 When it comes to alcohol consumption during pregnancy, there is no known safe level for a woman to consume at any time during pregnancy.4

Prevalence

Current research indicates that 2% to 5% of the US population has some form of FASD, with an estimated 40,000 infants born with FASD in the US each year.6 FASD is as common as autism spectrum disorder but remains underdiagnosed in North America, emphasizing the need for increased awareness, diagnosis, and treatments.2,4 According to the CDC, certain regions in the US have as much as 0.2 to 1.5 per 1,000 live births born with some degree of FASD.7 Diagnosis of FASD by healthcare providers remains low due to the impreciseness of self-reported maternal drinking histories, lack of sensitive biomarkers, social stigma, complexity of the diagnosis, low recognition of dysmorphic facial characteristics, and an overlap with differential diagnoses such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.8

Individuals with FASD experience a wide range of neurodevelopmental abnormalities, including difficulties with adaptive function, attentiveness, working memory, reasoning, self-control, motor function, social cognition, and linguistic and nonverbal learning, among other issues.9 Mild cases of FASD have subtle neurodevelopmental effects that do not generate clinical attention.8 Unfortunately, little research has been conducted on treatment strategies.10 Efforts have been made to improve identification and management of FASD with nonclinically referred groups, studies of school-based populations, international studies examining high-risk populations, advanced three-dimensional imaging of facial characteristics, and new neurobehavioral screening tools.8

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of FASD is often challenging due to the similarity of the signs and symptoms to those of other disorders and mothers’ underreporting of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Depending on the severity and extent of symptoms, a FASD diagnosis can include more than one classification. Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is considered the most involved disorder of the FASD spectrum. Individuals diagnosed with FAS present with central nervous system disorders, abnormal facial features, and growth problems. In addition, patients diagnosed with FAS may have difficulties with learning, memory, attention span, communication, vision, and hearing, or they may have a combination of these problems. Individuals with FAS tend to struggle in school and have trouble getting along with others. Those exposed to prenatal alcohol and diagnosed with some but not all the diagnostic characteristics of FAS are classified as a partial FAS.11

The effects of alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND) include intellectual disabilities and problems with behavior and learning. For example, children with ARND may do poorly in school; display difficulties with math, memory, attention, and judgment; and exhibit poor impulse control. Individuals with alcohol-related birth defects have problems with the heart, kidneys, bones, or hearing, or a combination of all of these.11

The last classification included under the FASD umbrella is neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE), which was first included as a recognized condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5 of the American Psychiatric Association in 2013. An ND-PAE diagnosis requires that the mother consume more than the minimal alcohol levels before the child’s birth. The American Psychiatric Association defines this level as more than 13 alcoholic drinks during any 30-day period of pregnancy or more than two drinks in one sitting.11

For a child or adolescent to receive a diagnosis of ND-PAE, he or she must exhibit symptoms in three scopes. The first is thinking and memory, such as when a child has trouble planning and may forget what he or she has already learned. Secondly, the child must display behavior problems such as severe tantrums, mood issues, and difficulty shifting from one task to another. Lastly, the child must exhibit difficulties with day-to-day living, including personal care (bathing, dressing) and problems playing with other children.

![TABLE 1. Suggested Questions Prior to the First Dental Appointment]() Common Physical Features

Common Physical Features

Some physical features associated with FASD include low body weight, shorter-than-average-height, and a smaller head circumference.12 Individuals with FASD may also exhibit distinct facial features, such as a flat philtrum (smooth ridge between the nose and upper lip), thin upper lip, and shortened distance between inner and outer corners of the eye, forming a wide-eyed appearance (Figure 1, page 31, and Figure 2).1 Dental hygienists may play an invaluable role in identifying FASD because of their extensive education on facial features and functions of the head and neck. While there is no cure for FASD, research has shown that early intervention therapy may improve a child’s development in skills such as speaking, walking, and interacting with others.11 If FASD is suspected, oral health professionals can provide referrals and collaborate with the patient’s physician or other members of the patient’s healthcare team to provide the best possible treatment.

Motor Function Delays

Motor delays can occur in children with FASD. Due to prenatal alcohol exposure, children with FASD may experience neurological impairment to the corpus callosum, cerebellum, motor cortex, and the peripheral nervous system, which may contribute to motor function difficulties. A meta-analysis conducted by Lucas et al13 reported that children with FASD experienced significant gross motor skill deficiencies, particularly with balance and coordination. Additionally, adolescents with motor impairments are more likely to experience problems with social skills, poor academic achievement, reduced self-sufficiency in everyday activities, less engagement in sports and leisure activities, increased anxiety, and low self-worth.13

Increasing health professional awareness of FASD and accompanying motor dysfunctions is critical to identifying and diagnosing the condition as early as possible. Moreover, comprehending the type of motor impairments associated with FASD is important to the ability of oral health professionals to determine best practices and optimal approaches for managing this population in the dental setting.

Taste/Texture Sensitivity and Nutrition Deficiencies

Children diagnosed with FASD may be more susceptible to intense responsiveness to smell, texture, taste, temperature, and/or appearance of food because of the neurodevelopmental anomalies associated with the disease. Consequently, children with FASD commonly experience more significant atypical eating behaviors than typically developing children due to the inability to interpret signals of the body feeling satiated.14 Children with FASD often display behaviors related to pica, a compulsive eating condition in which individuals consume nonfood objects such as dirt, clay, and peeling paint to satisfy their hunger.15 Children with FASD also experience issues in oral motor development, which may lead to delayed introduction to solid meals.

These oral motor developmental delays may impact the start of self-feeding and achievement of age-appropriate eating abilities, which can lead to nutritional deficits that significantly impact oral health into adulthood. Resulting malnutrition from FASD neurodevelopmental anomalies can weaken the immune system, increasing the incidence of gingivitis and other mouth infections. Deficiencies in vitamin A and vitamin C can lead to poor gingival healing time and increased gingival bleeding. Vitamin D insufficiency can reduce calcium and phosphate absorption, both of which are necessary for healthy tooth enamel composition.16 Preferences for eating soft foods may result in greater food adhesion to teeth, and oral aversion may impede the ability to brush and floss, increasing caries risk. Children with oral aversion may need sedation or general anesthesia to undergo dental examinations, dental prophylaxis, preventive treatments, or restorative care.

Oral Health Challenges

Individuals with developmental and intellectual disabilities are at increased risk for oral health issues.1,2 Physical limitations, co-morbidities, behavioral concerns, and access to care all impede this population’s ability to access dental health care. Limited research is available on the severity of oral disease among individuals with FASD. A retrospective study conducted at the University of Saskatchewan College of Dentistry between 2016 and 2019 looked at the oral health status and treatment needs of children between the ages of 6 and 14 with FASD.1 The study revealed that children with FASD were significantly older at their first dental visit, required disproportionally more public funding to pay for care, had higher primary/permanent dentition decayed, missing, filled teeth (dmft/DMFT) scores, greater treatment needs, and were more likely to require general anesthesia for dental treatment.

When it comes to effectively preventing and managing oral conditions in children, adolescents, and adults with FASD, oral health professionals need to understand the unique needs of this population. Children with FASD develop malocclusion with a significantly higher prevalence of crossbites.14 Mouth breathing, which is a common condition in children with FASD, can contribute to malocclusions with increased or decreased overjet, anterior and posterior crossbite, open bite, and contact point displacement—all of which increase the long-term risk of caries, occlusal trauma, and periodontal diseases. Therefore, the need for routine dental care and early orthodontic screening and treatment are particularly great for those with FASD.14

Given that snacking and eating between meals increase caries risk, the atypical eating pattern of patients with FASD possibly explains the higher dmft/DMFT score seen in research studies. Therefore, nutritional counseling and caries risk assessments conducted by oral health professionals may positively influence patients’ oral health. Given that malocclusions in patients with FASD are well-documented and sucking motions and mouth breathing may promote these malocclusions, dental hygienists should identify these habits at an early stage when referral for intervention is most beneficial.

Manual dexterity should also be evaluated in patients with FASD because difficulties in handwriting have been reported, affecting their ability to brush and floss properly. When treating patients with FASD, providing personalized self-care instruction with modifications is warranted to help them achieve the best plaque control possible.

Dental Appointment Management

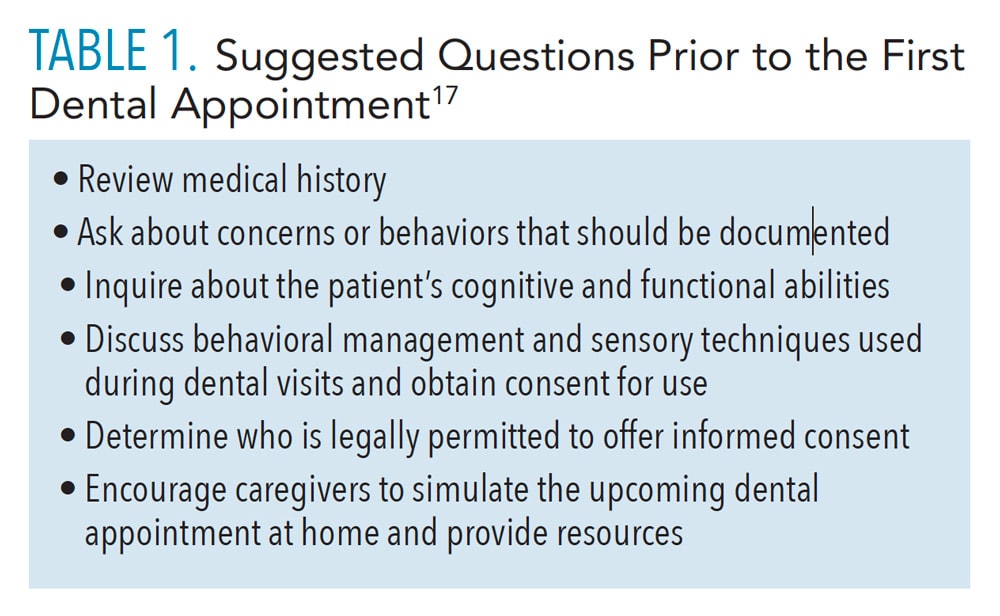

Prior to the dental appointment, a verbal interview should be scheduled with caregivers to address concerns, behaviors, patient preferences, and patient management approaches. As with any patient, dental health providers should exhibit empathy to the patient and caregivers by being responsive to their needs and concerns. During the verbal interview, caregivers may communicate information for the dental team to become more acquainted with the patient and their needs by using a prepared list of questions (Table 1).17

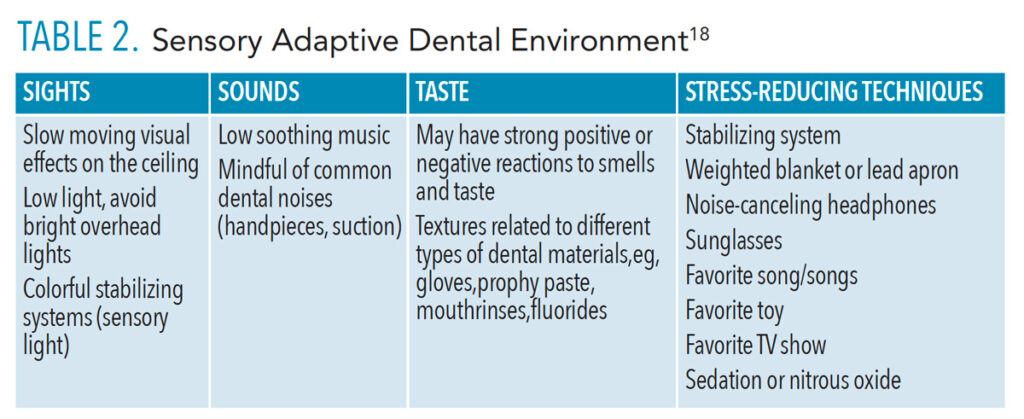

During the appointment, high-quality care should be provided as with any patient. Patients with FASD may have strong positive or negative reactions to smells, taste, and textures. Oral health professionals want to create a safe dental environment for patients with FASD by incorporating sensory adaptive dental environment approaches (Table 2, page 32).18

Additional Considerations

Individuals with FASD can also develop secondary conditions that may impact their systemic health as well as mental health. Children with FASD often do not perform well in school and are at increased risk of suspension, expulsion, and dropping out of school. An inability to get along with other children and poor relationships with teachers are often reasons cited for removal.19 Problems with anger management and difficulty understanding the motives of others can lead to violent and explosive situations. These individuals can be easily manipulated and persuaded to do illegal acts and become victims of crime themselves. Approximately 14% of children and 60% of adolescents and adults with FASD have problems with the law.19

Adults with FASD generally struggle to remain employed and live independently. Research has shown that not only do individuals with FASD experience an increased risk for cognitive disorders, but also for mental illness and psychological problems. The most frequently diagnosed disorders are ADHD; conduct disorder (aggression toward others and serious violations of rules, laws, social norms); substance abuse; depression; and anxiety.19 Research suggests that more than a third of individuals with FASD have drug and alcohol problems that require inpatient treatment.19 Individuals with FASD are also at higher risk for inappropriate sexual behaviors such as making unwanted advances and inappropriate touching. The likelihood of engaging in inappropriate sexual behaviors among those with FASD increases slightly with age: 39% in children, 48% in adolescents, and 52% in adults.19

Conclusion

The more knowledgeable oral health professionals are about FASD, the better they will be able to successfully provide dental care, which may require behavior modification techniques, customization of care regimens, and interprofessional referrals. A thorough understanding of FASD and its associated physical, intellectual, and behavioral implications will prepare clinicians to manage the oral health challenges of this patient population and improve their oral health outcomes.

References

- Da Silva K, Wood D. The oral health status and treatment needs of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;25:3497–3503.

- Brewer E. Aftercare instructions for oral piercings: an analysis of UK practice and its relevance in dentistry. Dental Health. 2017;6:12.

- Ornoy A, Ergaz Z. Alcohol abuse in pregnant women: effects on the fetus and newborn, mode of action and maternal treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:364–379.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More Than 3 Million US Women at Risk for Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancy. Available at: cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0202-alcohol-exposed-pregnancy.html. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Alert. Available at: pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa13.htm. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- Smith VC. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: FAQs of Parents & Families. Available at: healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/chronic/Pages/Fetal-Alcohol-Spectrum-Disorders-FAQs-of-Parents-and-Families.aspx. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease and Prevention. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Data & Statistics. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/data.html. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- Wozniak JR, Riley EP, Charness ME. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:760–770.

- Lange S, Shield K, Rehm J, Anagnostou E, Popova S. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: neurodevelopmentally and behaviorally indistinguishable from other neurodevelopmental disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:322.

- Boroda E, Krueger AM, Bansal P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of transcranial direct-current stimulation and cognitive training in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Brain Stimul. 2020;13:1059–1068.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FASDs: Treatments. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/treatments.html. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Basics about FASDs. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/facts.html. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- Lucas BR, Latimer J, Pinto RZ, et al. Gross motor deficits in children prenatally exposed to alcohol: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e192–e209.

- Blanck-Lubarsch M, Dirksen D, Feldmann R, Sauerland C, Hohoff A. Tooth Malformations, DMFT Index, Speech Impairment and Oral Habits in Patients with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4401.

- Amos-Kroohs RM, Fink BA, Smith CJ, et al. Abnormal eating behaviors are common in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. J Pediatr. 2016;169:194–200.

- Norwood Jr KW, Slayton RL, Council on Children With Disabilities; Section on Oral Health. Oral health care for children with developmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2013;131:614–619.

- Autism Speaks. ATN/AIR-P Tool Kit for Dental Professionals. Available at: autismspeaks.org/tool-kit/atnair-p-tool-kit-dental-professionals. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- OscarPD. Oral Special Care Academic Resources. Available at: oscarpd.ro. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FASDs: Secondary Conditions. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/secondary-conditions.html. Accessed January 24, 2022.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2022;20(2):31-34.