Managing Gingival Recession

What the research reveals about the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of this common problem.

This course was published in the August 2012 issue and expires August 31, 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define gingival recession.

- Explain the etiology of gingival recession.

- Discuss the classification of gingival recession.

- Identify the indications for treatment of gingival recession.

- Detail the various options available for treatment.

Gingival recession is the apical migration of the gingival margin that results in exposure of the root surface.1 It is very common among American adults, affecting more than 23 million people.2,3 Men are at greater risk than women and African Americans experience more gingival recession than other ethnic groups.3 It occurs most frequently on buccal surfaces and is more common among those older than 50.3 Although many people exhibit localized or generalized gingival recession, few present with any symptoms. Gingival recession can cause esthetic problems, root sensitivity, root caries, and faster wear of the exposed root surface.

ETIOLOGY OF GINGIVAL RECESSION

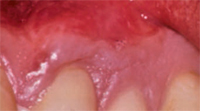

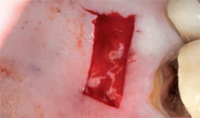

Many factors contribute to gingival recession, including trauma and inflammation, as well as anatomic and iatrogenic factors. Trauma due to aggressive toothbrushing in clinically healthy gingiva is a leading cause of gingival recession (Figure 1). Trauma caused by lip and tongue piercing can also contribute to gingival recession. Gingival inflammation due to poor oral hygiene and periodontal diseases may lead to gingival recession (Figure 2). A certain type of anatomy predisposes patients to gingival recession, including a thin gingival biotype, prominent frenal attachment (Figure 3), and malaligned teeth, especially when associated with thin facial bone. Iatrogenic factors, such as improper restorations invading the biological space, can result in gingival recession as well.

CLASSIFICATION OF GINGIVAL RECESSION

Several classifications have been proposed to facilitate the diagnosis of gingival recession with Miller’s classification being the most frequently used.4 Miller’s classification is based on the morphology of the injured periodontal tissues and can help predict the final amount of root coverage following a free gingival graft procedure. The classification sorts the recession patterns into four types based on evaluation of soft and hard periodontal tissues (Table 1).

INDICATIONS FOR TREATMENT

Many patients experience gingival recession without exhibiting symptoms. However, when any of the following indications is present, treatment should be initiated.

- Root sensitivity as a result of gingival recession.

- Poor self-care with an increased risk of cervical caries. When the gingival contour is altered in the recessed area, this will prevent adequate plaque removal (Figure 2).

- Lack of keratinized gingiva that results in a mucogingival defect. This is controversial because new evidence suggests that with good self-care, clinically healthy marginal gingiva can be maintained, even in areas with less than 1 mm of keratinized tissue.5

- Esthetic concerns. The appearance of gingival recession may be unacceptable to some patients, especially if the recession is present in the maxillary and mandibular incisors.

- Progression of the recession defect. An increase in recession between recare visits is an indication for treatment.

- Orthodontic treatment. Gingiva can be augmented prior to starting orthodontic treatment, which may cause an alveolar bone dehiscence. This will reduce the risk of soft tissue recession.

MANAGEMENT

Minimally invasive treatments should always be implemented first. Plaque and calculus should be removed so inflammation is reduced. Patient education in self-care, including the use of a soft toothbrush and proper toothbrushing technique, should also be provided.

A variety of surgical treatments are used to treat gingival recession. Mucogingival surgery includes periodontal surgical procedures designed to correct defects in the morphology, position, and amount of gingiva surrounding the teeth. The goal is to increase the keratinized tissue around teeth and obtain root coverage. The coronally positioned flap technique positions the coronal flap to obtain root coverage. The flap retains its own blood supply, which is a distinct advantage. This surgery is useful when the keratinized gingiva is at least 3 mm wide beyond the area of recession with a gingival thickness of at least 1 mm.6 This procedure is most effective in covering localized Miller’s class I recession defects.

Pedicle grafts develop partial thickness flaps around the involved teeth, sliding the entire flap the width of half a tooth and placing interdental papillary tissues over the buccal surfaces of the affected teeth.7,8 Pedicle flaps also retain their own blood supply. The vascularity nourishes the graft, facilitating the re-establishment of vascular union with the recipient site (Figure 4 and Figure 5). This procedure can be used only if there is an adequate band of keratinized gingiva adjacent to the recession site. Free epithelialized autogenous gingival grafts are not routinely used in root coverage procedures but are mostly done to increase the zone of keratinized gingiva.9 The procedure uses a gingival graft with some connective tissue harvested from the hard palate. Grafts are primarily harvested from the palate, although edentulous areas and attached gingiva can serve as potential donor sites as well. Free gingival grafting has also been used as a single procedure to cover denuded root surfaces.10

Although free gingival grafts are easy to harvest, they have several disadvantages. The involvement of a second surgical site with an open donor site wound can cause significant pain and morbidity. There is also a lack of color match with the surrounding tissue and they heal with a scar-like appearance (Figure 6 to Figure 9). These disadvantages prevent their use in the esthetic zone.

In subepithelial connective tissue autografts, the graft is obtained from a different site within the same individual. The technique elevates a partial thickness flap with two vertical releasing incisions on the recipient site, followed by a placement of the graft harvested from the palate.11 The flap is coronally positioned over the connective tissue graft to obtain double vascular supply (Figure 10 to Figure 12). This technique requires a second surgical site. However, the donor site can be closed, thus creating minimal post-operative discomfort. The subepithelial connective tissue graft is a predictable technique for obtaining root coverage and is considered the “gold standard” procedure in the treatment of Miller’s class I and class II recession defects.12 In connective tissue allografts, the allograft is obtained from human donor dermis, which is then processed so that all of the immune cells that preserve the acellular matrix are removed. A connective tissue allograft can cover multiple recession defects without a second site surgery (Figure 13 to Figure 16). Connective tissue allografts can be used to successfully cover roots and gain keratinized gingiva.13

Guided tissue regeneration (GTR) is one of the newest techniques for addressing gingival recession. Regeneration is a biologic process through which the architecture and function of lost tissues are completely restored. GTR uses a barrier/membrane over the root surface to prevent epithelial downgrowth. The results of GTR for gingival grafting are mixed. Some studies report root coverage of 72%,14 whereas others show root coverage as high as 95%.15 These results, however, are not sustained for a prolonged period. Harris reported that the initial high percentage of root coverage obtained at 6 months post-treatment decreased to 58% after a mean of 25 months post-surgical evaluation.16 Combining different root coverage procedures may increase their success. Wennstorn and Zuchelli combined a coronally positioned flap with a connective tissue graft procedure.17 They treated 103 Miller’s class 1 and class II defects with a 98.9% success rate for the combination approach.

POST-SURGICAL OUTCOME

Sutures are typically removed 7 days to 10 days following mucogingival surgery. At the 1 month follow-up, the treated area should demonstrate recession coverage. Gingival healing is evaluated at 3 months and 6 months. The surgical area must not probed until the 3 month post-operative visit to allow for complete healing. Complete root coverage is based on whether the marginal tissue reaches the cemento enamel junction, clinical attachment is present, sulcus depth is 2 mm or less, and bleeding on probing is absent.

There are a number of factors that affect the outcome of root coverage procedures. The dimension of the recession significantly impacts the amount of root coverage that can be obtained. Less favorable outcomes are more common with wide (>3 mm) and deep (>5 mm) recessions. Lack of interproximal bone, as seen in Miller’s class III and IV recessions, can negatively impact root coverage. Smoking and poor oral hygiene also contribute to less than optimal outcomes.

Creeping attachment can help attain root coverage. Creeping attachment is the post-surgical migration of the gingival marginal tissue in a coronal direction over portions of a previously denuded root.18 Creeping attachment is detected approximately 1 month to 12 months after graft surgery with an average coverage of about 1 mm.19 It may continue to progress beyond the first post-operative year.

CONCLUSION

Patients who present with nonprogressing gingival recession without root sensitivity are best treated by informing patients of the issue, providing self-care education, and monitoring the sites. When treatment is indicated, factors that may negatively affect treatment need to be addressed prior to any intervention. Sometimes what clinicians deem as “good” root coverage is not an acceptable esthetic result for the patient.20 Patient expectations must be assessed to ensure they are realistic. Informing patients about the severity of the gingival recession after the initial assessment is completed can help them anticipate the expected treatment outcome. Long-term benefits of gingival recession treatment with grafts include increased root coverage, greater thickness of tissue, and improved resistance to further recession.

REFERENCES

- Saha S, Bateman GJ. Mucogingival grafting procedures—an update. Dent Update.2008;35:561–568.

- Sarfati A, Bourgeois D, Katsahian S, Mora F,Bouchard P. Risk assessment for buccal gingival recession defects in an adult population. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1419–1425.

- Albandar KM, Kingman A. Gingival recession,gingival bleeding, and dental calculus in adults 30 years of age and older in the United states,1988-1994. J Periodontol. 1999;70:30–43.

- Miller PD, Jr. A classification of marginal tissue recession. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent.1985;5:9–13.

- Miyasato M, Crigger M, Egelberg J. Gingiva lcondition in areas of minimal and appreciable width of keratinized gingiva. J Clin Periodontol.1997;4:200–209.

- Allen EP, Miller PD. Coronal positioning of existing gingiva; short term results in the treatment of shallow marginal tissue recession.J Periodontol. 1989;60:316–319.

- Grupe HE, Warren RF. Repair of gingival defects by a sliding flap operation. J Periodontol.1956;27:290–295.

- Kassab MM, Badawi H, Dentino AR.Treatment of gingival recession. Dent Clin N Am. 2010;54:129–140.

- Sullivan HC, Atkins JH. Free autogenous gingival grafts. I. Principles of successful grafting. Periodontics. 1968;6:121–129.

- Holbrook T, Ochsenbein C. Complete rootcoverage of the denuded root surface with a one stage gingival graft. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1983;3:9–27.

- Langer B, Langer L. Subepithelial connective tissue graft technique for root coverage. J Periodontol. 1985;56:715–720.

- Chambrone L, Chambrone D, Pustiglioni FE,Chambrone LA, Lima LA. Can sub-epithelial connective tissue grafts be considered the gold standard procedure in the treatment of Miller class I and Class II recession-type defects? J Dent. 2008;36:659–671.

- Henderson RD, Greenwell H, Drisko C, et al.Predictable multiple site root coverage using an acellular dermal matrix allograft. J Periodontol. 2001;72:571–582.

- Pini Prato GP, Tinti C, Vincenzi G, Magnani C,Cortellini P. Guided tissue regeneration versus mucogingival surgery in the treatment of human buccal gingival recession. J Periodontol. 1992;63:919–928.

- Harris RJ. A comparison of 2 root coverage techniques: Guided tissue regeneration with a bioabsorbable matrix style membrane versus a connective tissue graft combined with coronally positioned pedicle graft without vertical incisions. Results of series of cases. J Periodontol. 1998;69:1426–1434.

- Harris RJ. GTR for root coverage: a long term follow-up. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent.2002;22:55–61.

- Wennstrom JL, Zucchelli J. Increased gingival dimensions. A significant factor for the successful outcome of root coverage procedures.A 2 year prospective clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:770–777.

- Goldman H, Schulger S, Fox L, Cohen DW.Periodontal Therapy. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Co; 1964:560.

- Miller PD, Jr. Root coverage using free soft tissue autograft following citric acid application.III. A successful and predictable procedure in areas of deep wide recession. Int J Period Rest Dent. 1985;5:14–37.

- Zucchelli G, De Sanctis M. Treatment ofmultiple recession-type defects in patients with esthetic demands. J Periodontol. 2000;9:1507–1514.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2012; 10(8): 18, 21-23.