In Memoriam: A Lasting Legacy

The matriarch of dental hygiene, Esther M. Wilkins, BS, RDH, DMD, lives on through her seminal textbook, her passion for the profession of dental hygiene, and her personal impact on friends and colleagues.

I first met Esther M. Wilkins, BS, RDH, DMD, at Boston’s Tufts University School of Dental Medicine in August 1973. At the time, I was a young assistant professor of dental hygiene and periodontics at the University of Southern California (USC) School of Dentistry in Los Angeles. When my husband, Gordon Pattison, DDS, was accepted to the Periodontology Residency Program at Boston University, we moved from Los Angeles to Boston. I was the director of the sophomore clinical periodontics course at USC and Esther was teaching the same course at Tufts. I was excited at the prospect of meeting Esther and possibly teaching this course with her.

I received an appointment at Tufts and the Forsyth School for Dental Hygienists, where Esther was also a faculty member. From 1973 to 1975, we shared a small office, working closely together and sealing the foundation of a lifelong friendship that was to be filled with wonderful memories.

THE TEXTBOOK THAT LIVES ON

Esther is probably best known for her textbook Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist, now in its 12th edition. The book derived from an assortment of handouts that she created when she started the Dental Hygiene Program at the University of Washington School of Dentistry in 1950. The first edition was published in 1959 and is now translated into six languages. It has served as the premier textbook for dental hygienists around the world ever since.

Esther became interested in dental hygiene during her senior year at Simmons College in Boston when a professor discussed careers in public health. After earning a Bachelor of Science degree, she entered the Forsyth School for Dental Hygienists in 1938. Upon completion of dental hygiene school, Esther began practicing in a pediatric dental office in Manchester-by-the Sea, Massachusetts. Her love of learning was never satisfied, and she decided to enter dental school at Tufts, undaunted by the fact that only 2% of dentists at the time were women. She graduated in 1949 and was recruited by the University of Washington in 1950.

In 1964, she happily moved back to New England to enter the Tufts’ program in periodontology. After successfully completing the challenging course of study, Esther began her 45-year teaching career at Tufts.

LEADING BY EXAMPLE

I have marveled at Esther’s intelligence, resilience, vigor, and, most of all, her incredible work ethic for more than 40 years. Many periodontists and dental hygienists are good teachers, researchers, and writers, but what made Esther stand out was her indefatigable motivation, perseverance, and total devotion to making each edition of her book better and more comprehensive than the last. She prepared for every lecture as if it were her first and approached every course and meeting with enthusiasm. Esther began giving continuing education courses in 1967 and presented more than 1,000 courses, traveling to all 50 states and a variety of countries, including South Africa, Japan, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia.

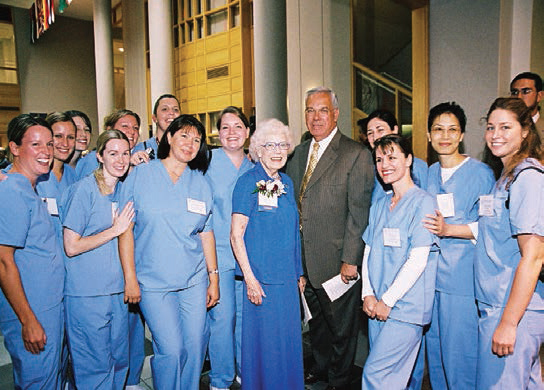

Esther greeted old friends and new acquaintances with exuberance, and her infectious spirit of optimism was fueled each time she met with students. Practicing dental hygienists and students alike treated her with reverence because they sincerely appreciated all they had learned from her book. She especially loved taking pictures with them because they inspired her to keep working on yet another edition.

Her only breaks from the book were travelling to lecture or attend meetings and dinners, where she might enjoy a beer and dance the night away. Her love of dancing was legendary, and she often stayed on the dance floor well after midnight when all of the younger dental hygienists had gone to bed!

MATERNAL CONNECTION

My mother was also born in 1916, but she passed away 10 years ago at age 90. Esther always knew that I was closer to her than to my own mother, who spoke very little English. My Japanese was never good enough to have meaningful conversations with my mother, and she never understood my desire to excel as a professional woman. Esther felt sorry that my mother did not appreciate my professional accomplishments, as she was a role model for career success when few women were part of the workforce.

My mother always assumed that I had to work long hours, write books, and lecture with Esther to earn extra money. She thought that as a periodontist’s wife, I should not work at all, but rather drive a Mercedes, shop on Rodeo Drive, and get my hair done every week. She never did any of those things but she aspired to have a daughter who could. In every way, since we had shared that tiny office at Tufts, Esther gave me the continuous support and encouragement that I longed to receive from my own mother. Esther and I were in agreement about so many things in life that we made sure to keep in touch through all these years.

LONG-TERM IMPACT ON NONSURGICAL PERIODONTAL THERAPY

The greatest lesson I learned from Esther as a young clinician was to always probe first and scale thoroughly to the base of the pocket. She was passionate about the dental hygienist’s role in prevention, and one of her proudest accomplishments was when the Forsyth School of Dental Hygiene at MCPHS University named its new state-of-the-art dental hygiene clinic after her in 2004.

During my last conversation with Esther, we both lamented the prevalence of periodontitis in the United States and the fact that too many dental hygienists still do not probe regularly and many do not scale subgingivally deeper than a few millimeters. She was very concerned that the educational emphasis on the most important foundations of periodontal therapy, especially meticulous initial therapy and maintenance, was being muted in an era of implants and adjunctive procedures. We discussed how many patients with periodontitis are treated by thousands of dentists and dental hygienists who do not scale subgingivally at all.

We tried hard to think of what more we could do to affect meaningful change in this state of affairs. Remembering those discussions now makes her last email to me on November 27, 2016, even more poignant. An instrument company had asked Esther to choose a favorite instrument to be designated as a commemorative instrument on the occasion of her 100th birthday. In her last email, she asked me to write detailed instructions on the use of mini-bladed Gracey curets to be distributed with the instruments. She wanted more dental hygienists to use mini-bladed instruments in hopes they would scale deeper subgingivally. This was her last professional request to me. To honor her memory and her lifelong contributions to dental hygiene and periodontics, Esther would want me to pass on her last message: Probe more, scale deeper, and educate patients better about the prevention of oral diseases.

Conclusion

I was honored to be among a small group of Esther’s closest friends that gathered in Hudson, New Hampshire, on Friday, December 9, to celebrate her 100th birthday. Unfortunately, Esther had a stroke early that morning, so she was not able to join us at her party that she was so looking forward to attending. She left us three days later, surrounded by the love of friends and family, with great dignity and serenity.

We will always remember our dear colleague, friend, teacher, and mentor, Dr. Esther Wilkins, with great affection and respect. We have lost a true icon who will never be replaced. We will miss her warmth, energy, dedication, stamina, and boundless passion for teaching and learning. She touched us all in so many ways. Esther spent her entire life leading by example, continually striving and advocating for excellence to move our profession forward.

I would like to close with these sentiments written by Pamela J. Bretschneider, PhD, Esther’s close friend and biographer: “Dr. Wilkins’ legacy will continue to inspire future generations throughout the world who will follow in her footsteps. The grand matriarch, a pioneer who loved her profession with untiring energy, who wrote the road map for practice, who insisted on excellence, will dance with us forever. She once said her words to live by were: ‘Life isn’t about waiting for the storm to pass. It’s about learning to dance in the rain.”

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2017;15(1):12,14-15.