Good Start to Oral Health

As more pediatric patients seek treatment in general dental practices, clinicians need to be well versed in caries prevention.

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) recommends that children receive their first dental examination by age 1 or within 6 months of their first tooth erupting.1 Parents/caregivers may not comply with this recommendation because they feel that a dental visit in the first year of life is too early. Studies examining the cost-effectiveness of early and regular preventive visits show that they pay off in the long-run.2 The purpose of the age-1 dental visit is to establish a dental home, perform a comprehensive examination and caries risk assessment, identify early signs of pathology, apply fluoride, and educate parents/caregivers about oral health.

Due to the recommendation for the age-1 dental visit and the expansion of dental coverage for children under the Affordable Care Act, the number of pediatric patients seeking dental care will most likely increase.3,4 Consequently, oral health professionals should be prepared to provide age-specific oral health care instructions and preventive education to children of all ages.

THE DENTAL VISIT

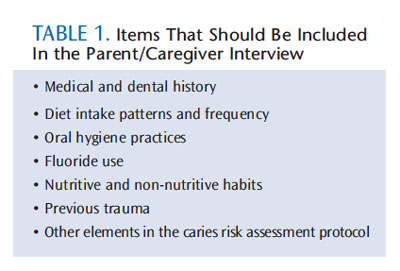

Pediatric dental visits should include a thorough parent/caregiver “interview” at the beginning of the appointment. This is followed by a caries risk assessment, prophylaxis, examination, fluoride application, and age-appropriate anticipatory guidance with oral hygiene instructions. Additional procedures, such as radiographs, are completed when deemed appropriate. Table 1 includes a list of the key items that should be part of a parent/caregiver interview.

Pediatric dental visits should include a thorough parent/caregiver “interview” at the beginning of the appointment. This is followed by a caries risk assessment, prophylaxis, examination, fluoride application, and age-appropriate anticipatory guidance with oral hygiene instructions. Additional procedures, such as radiographs, are completed when deemed appropriate. Table 1 includes a list of the key items that should be part of a parent/caregiver interview.

The parent/caregiver interview needs to be conducted using open-ended questions, and, if possible, the patient should also be involved. Data from this interview are used in conjunction with the clinical findings to determine caries risk. The caries risk assessment is a tool used to ascertain the likelihood of a child developing future caries by evaluating the balance/imbalance between risk and protective factors.5,6 The infant exam is typically performed in the knee-to-knee position, and a toothbrush is used to perform the prophylaxis.5 Some parents/caregivers may not perceive the value of a toothbrush prophylaxis, so it is important they understand the following: teeth must be clean so they can be examined thoroughly; a toothbrush prophylaxis allows for demonstration of appropriate toothbrushing technique; and a rubber cup or scaling is not generally necessary in young children because most do not have calculus or extrinsic stains.7

Among young children, parents/caregivers are primarily responsible for influencing diet and hygiene practices and, thus, should be the focus of oral health education. Specifically, oral health professionals should allow parents/caregivers to observe proper hygiene techniques, identify teeth with significant plaque accumulation, pinpoint teeth with early or advanced caries, and discuss other areas of concern during the course of the prophylaxis and exam. When the child is old enough, he or she should be given a hand mirror to observe and participate. The dental team will then summarize the findings, develop a prevention/treatment plan, and determine which recommendations will be most beneficial.

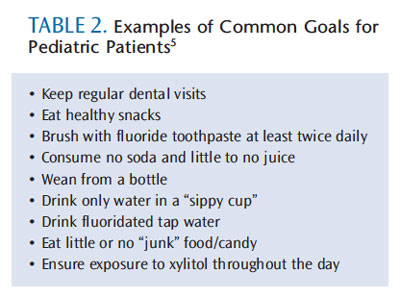

Oral health professionals can use motivational interviewing to encourage behavior change and increase compliance.8,9 In this process, the parents/caregivers play an active role in identifying goals that can be achieved in an effort to strengthen their intrinsic motivation for change.10 When providing education, the tendency is to provide an extensive list of recommendations, but this can be overwhelming for parents/caregivers and children. Studies indicate that oral health instructions should identify one or two key goals through the motivational interviewing process.5 Table 2 provides examples of common goals that the oral health professional and parent/caregiver can agree on.5 At subsequent appointments, progress toward meeting these goals can be revisited. Once achiev

ed, new goals can be established. Parents/caregivers may ask why it is important to invest time, energy, and resources into “baby teeth.” Every dental professional should be prepared to answer this question. Primary teeth serve important functions related to eating, speaking, and development. Caries and early loss of primary teeth can affect learning, communication, nutrition, and overall well-being.

ed, new goals can be established. Parents/caregivers may ask why it is important to invest time, energy, and resources into “baby teeth.” Every dental professional should be prepared to answer this question. Primary teeth serve important functions related to eating, speaking, and development. Caries and early loss of primary teeth can affect learning, communication, nutrition, and overall well-being.

CARIES MANAGEMENT

Just as the clinical presentation of caries varies widely, so do treatment approaches. A number of factors influence the decision to select the timing and type of treatment, such as the rate and extent of decay and the child’s psychosocial development.

In the early stages of the caries process, affected enamel is noncavitated and chalky in appearance. One important reason for early and regular dental visits is to identify these incipient lesions, so they can be arrested or recalcified with fluoride varnish and good oral hygiene.11 Adjuncts to fluoride therapy include the use of chlorhexidine gluconate and povidone iodine.12 While these are effective at reducing the bacterial load, the evidence is mixed regarding their efficacy as anticaries strategies.13–16 Whichever modality is chosen, a child with an active caries process is considered high risk and should be seen on a 3-month to 6-month schedule.5,6 Children who are at low-caries risk require less frequent recare appointments.

When a lesion has penetrated enamel and becomes cavitated, oral health professionals must decide whether treatment is necessary or if it can be delayed. This decision is based on a balance between the rate/extent of decay and the likelihood that the child will comply with treatment.17 When the child is young and less likely to cooperate during restorative care, this decision can be complex. Very young children with cavitated lesions may require interim restorations with the use of a spoon or slow-speed handpiece for caries excavation followed by placement of a restorative material, such as glass ionomer.18 The purpose of this approach is to remove the most active part of the lesion,19 avoid the use of anesthetic agents, and buy time until the patient is old enough to cooperate for a definitive restoration. If children have significant treatment needs and are not able to comply with restorative care, then advanced behavior guidance, such as protective stabilization, moderate sedation, or general anesthesia, may be necessary.20

If primary prevention is not successful, the hope is that early and regular dental visits will slow the progression of dental caries and allow for early detection.11 Although caries at any age is unfavorable, a child who has a small cavity at age 5 is in a better situation than a child with multiple large cavities at age 3. An older child with fewer treatment needs will likely cooperate for definite restorative care under local anesthesia, with or without the use of nitrous oxide.

Nearly 90% of caries lesions found in school-aged children occur in the pits and fissures. Sealants on permanent molars provide a cost-effective way to reduce the risk of caries in these teeth. Consequently, sealants should be placed on at-risk permanent molars when they can be isolated adequately. Subsequent recare should include verifying that sealants are still present and replacing or repairing sealants when appropriate. Though sealants provide a means of reducing caries in pits and fissures, they do not prevent gingival disease or reduce the risk of caries to smooth surfaces, so self-care is still important.

COMMUNICATION PRINCIPLES

Most people know they should brush twice a day with fluoride toothpaste and floss daily, yet compliance with these recommendations remains low.21 Parents/caregivers may describe a number of reasons for noncompliance, such as children who are uncooperative, competing interests that reduce the focus on oral health, the belief that cavities are inevitable, and lack of oral health knowledge. 21,22 The goal of oral health professionals is to help parents/caregivers understand and carry out these recommendations.

The general public likely does not have a full understanding of the mechanisms of oral diseases or dental terminology. Oral health literacy—the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand the necessary information to make appropriate oral health decisions—is a key factor in improving outcomes.23 Individuals with low oral health literacy are less likely to utilize preventive services and maintain a regular recare schedule. They are also at greater risk of caries and more apt to use emergency services to address oral health problems.24 As such, dental staff must evaluate patients’ oral health literacy and use simple and direct messages, seek feedback, verify parents’/caregivers’ understanding with open-ended questions, and avoid dental jargon.

When communicating oral health information, clinicians should use visual aids, such as dental models and graphics. When possible, parents/caregivers should engage in “teach back”—where they participate and demonstrate their capacity to perform a task, such as their ability to floss a model or brush their child’s teeth with the proper technique. Some people learn by watching or doing, while others learn by listening. The process of explaining, demonstrating, and engaging parents/caregivers in hands-on participation should achieve the most favorable outcomes for all learning styles.

IMPLEMENT KID-FRIENDLY DENTAL PRODUCTS

Many oral health professionals hand parents/caregivers a “goodie bag” containing a toothbrush, toothpaste, floss, mouthwash, and other oral health products. Without instruction, these products can be overwhelming. Parents/caregivers may be unsure about which products should receive the greatest focus. The AAPD recommends that parents/caregivers

begin flossing their children’s teeth once the interproximal spaces between primary teeth are closed, as they are no longer cleanable with a toothbrush alone.25 Once children obtain the necessary dexterity, they should begin flossing their own teeth. Clinicians need to provide children with instruction on how to form a “C” shape with the floss around each tooth. Barriers to compliance with this recommendation include lack of knowledge and difficulty with flossing. A number of manufacturers make innovative tools to encourage children to see flossing as an integral part of oral hygiene and to help them floss more successfully. Flossers with child-sized handles designed in unusual shapes, such as crayons or dinosaurs, that feature bright colors and popular characters, as well as floss tools designed like nunchucks, can entice children to make flossing a part of their daily routine.

Fluoride mouthrinses may be appropriate for children who are able to expectorate the product and not swallow it, but they are never substitutes for proper brushing and flossing. Mouthrinses should only be used as adjuncts, depending on caries risk. Another frequently asked question is whether power toothbrushes are better than manual toothbrushes. While there are a number of industry-sponsored studies that support the use of power toothbrushes, manual toothbrushes can be just as effective when the proper technique, duration, and frequency are implemented.26 For this reason, one of the best giveaways is a 2-minute timer so children can monitor how long they brush. However, some children enjoy using power toothbrushes better than manual toothbrushes, which can increase compliance. Toothbrushing with a soft-bristled appropriately-sized toothbrush should begin when the first teeth begin to erupt.25 A wet cloth can also be used to clean infants’ teeth between feedings. Initially, toothbrushing is performed solely by the parent. This can be done with the child lying down or using the knee-to-knee position with two adults. Toddlers may enjoy chewing on toothbrushes, but it is important for parents/caregivers to continue performing twice-daily toothbrushing for the child. In fact, parents/caregivers should play an active role in toothbrushing until the child has developed the manual dexterity and an understanding of proper brushing technique. This normally occurs around age 8, but, even then, parents/caregivers need to reinforce brushing frequency and proper technique. One strategy that can improve compliance is to encourage parents/caregivers and children to brush together. This reinforces adult brushing habits, cuts down on the time needed for oral hygiene, allows for direct supervision of the child, and enables the parent to model appropriate brushing techniques.

Although many infant products with rubber bristles make great gum stimulators and teething toys, they are less effective for plaque removal. Consequently, they should not be used as substitutes for toothbrushes. Cold teething rings and other soft teething products stimulate the gums and may alleviate discomfort when primary teeth are erupting.25 Topical benzocaine products are marketed as a way to alleviate teething discomfort in infants, but they should not be used in children younger than 2, due to an increased risk of methemoglobinemia.27

Many parents/caregivers are concerned about the ingestion of fluoride in young children. The AAPD recommends the use of fluoride toothpaste for dentate children of any age.28 This means the amount of toothpaste placed on a child’s toothbrush must be monitored. Children younger than 2 should use only a smear of toothpaste (0.125 g), while children age 2 to 5 should use a pea-sized amount (0.25 g).28 Dental professionals should demonstrate appropriate age-specific quantities since most parents/caregivers are unsure of what the correct amount looks like.29 It does not matter whether a regular or children’s toothpaste is used because the fluoride content in most nonprescription toothpaste is the same. While many fluoride-free “training toothpastes” are available, they are of little benefit and send the wrong message that fluoride toothpastes are not safe for young children.28

CONCLUSION

In order to decrease the burden of disease, prevention should be emphasized. When necessary, treatment modalities and caries control measures should be implemented based on the rate and extent of decay and the behavior of the child. Although dental professionals may assume that oral health literacy is commonplace, parents/caregivers have wide variations in their understanding of oral health concepts. After providing oral health information, dental professionals should use motivational interviewing to identify one or two goals that the parent/caregiver can focus on prior to the next appointment. This identifies top priorities for the parent/caregiver and avoids diluting key messages with too much information. To increase the likelihood of compliance, kid-friendly products can be recommended, but brushing with fluoride toothpaste and flossing regularly should be emphasized as the most effective strategies to achieve and maintain oral health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author would like to thank Nicholas Salomon for his assistance with the images for this article.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the Dental Home. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35(Suppl):24–25.

- Lee JY, Bouwens TJ, Savage MF, Vann WF Jr. Examining the cost-effectiveness of early dental visits. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:102–105.

- Discepolo K, Kaplan AS. The patient protection and affordable care act: effects on dental care. NY State Dent J. 2011;77:34–38.

- Paladino JC. Impact of the Affordable Care Act on dentistry. Todays FDA. 2013;25:58–59.

- Ramos-Gomez FJ, Crall J, Gansky SA, Slayton RL, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment appropriate for age 1 dental visit (infants and toddlers). J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:687–702.

- Fontana M, Zero DT. Assessing patients’ caries risk. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;37:1231–1239.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on the role of dental prophylaxis in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33(Suppl):151–152.

- Weinstein P, Harrison R, Benton T. Motivating parents to prevent caries in their young children: one year findings. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:731–738.

- Kay EJ, Logam HL, Jakobsen J. Is dental health education effective? Systematic review of current evidence. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:231–5.

- Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is Motivational Interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23:325–334.

- Featherstone JDB. Caries prevention and reversal based on the caries balance. Pediatr Dent. 2006;26:128–132.

- Milgrom P, Chi DL. Prevention-centered caries management strategies during critical periods in early childhood. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2011;39:735–741.

- Autio-Gold J. The role of chlorhexidine in caries prevention. Oper Dent. 2008;33:710–716.

- van Rijkom HM, Truin GJ, van’t Hof MA. A meta-analysis of clinical studies on the caries-inhibiting effect of chlorhexidine treatment. J Dent Res.1996;75:790–795.

- Nowak A, Casamassimo PS. Using anticipatory guidance to provide early dental intervention. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:1156–1163.

- Lopez L, Berkowitz R, Spiekerman C, Weinstein P. Topical antimicrobial therapy in the prevention of early childhood caries: a follow-up report. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24:204–206.

- Nelson, TM. The continuum of behavior guidance. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:129–43.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): unique challenges and treatment options. Pediatr Dent. 2010;32(Suppl):45–47.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on interim therapeutic restorations. Pediatr Dent. 2010;32(Suppl):39–40.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Clinical guidelines on behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33(Suppl):161–173.

- Inglehart M, Tedesco LA. Behavioral research related to oral hygiene practices: a new century model of oral health promotion. Periodontol 2000. 1995;8:15–23.

- Backdash B. Current patterns of oral hygiene product use and practices. Periodontol 2000. 1995;8:11–14.

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Oral Health Literarcy. Available at:?iom.edu/Reports/2013/Oral-Health-Literacy.aspx. Accessed Novembe 22, 2013.

- Horowitz AM, Kleinman DV. Oral health literacy: the new imperative to better oral health. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52:333–344.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on infant oral health care. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35(Suppl):137–141.

- Robinson PG, Deacon SA, Deery C, et al. Manual versus powered toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD002281.

- Food and Drug Administration. Benzocaine Topical Products: Sprays, Gels And Liquids—Risk of Methemoglobinemia. Available at: www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm250264.htm Accessed November 21, 2013.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on fluoride therapy. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33(Suppl):153–155.

- Thomas AS. Parents’ interpretation of instructions to control fluoride toothpaste application [dissertation]. Seattle: University of Washington; 2011.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2013;11(12):30,32,34.