Regulatory Update

Here are tips to ensure compliance with OSHA’s new Revised Hazard Communication Standard.

Most oral health professionals would not cite the risk of injury due to chemical exposure as one of their main workplace concerns. While dental offices typically do not store large amounts of chemicals, inherent risks still remain. Chemical exposure to items such as disinfectants and acrylic materials in the clinical setting can result in serious health consequences. These problems can range from short-term issues to life-threatening conditions, including damage to the heart, kidneys, liver, and lungs.1

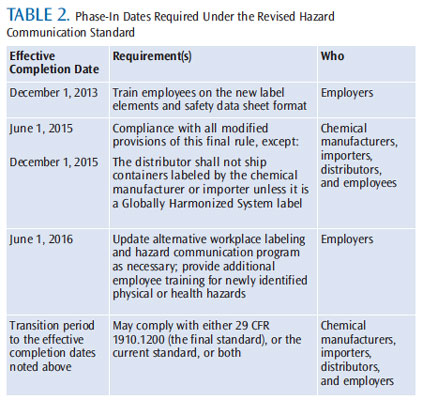

To help minimize the threat of chemical exposure in the workplace, the United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) recently revised its Hazard Communication Standard (HCS). The revised Standard Final Rule was issued on March 26, 2012, with the first phase becoming effective on December 1 of this year. The revised HCS will be fully implemented by 2016. The changes bring the United States into alignment with the United Nations Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals—further improving the health and safety protections for American workers.2 The revised standard is expected to prevent an estimated 585 injuries and illnesses annually.3

Designed to ensure that information about chemical threats and associated protective measures are broadly disseminated, the HCS requires chemical manufacturers and importers to evaluate the hazards of the chemicals they produce or import. They must then provide information on the labeling of their shipping containers, as well as more specific details via safety data sheets (SDSs). Employers with hazardous chemicals in their workplaces must prepare and implement a written hazard communication program, ensuring that all containers are properly labeled, employees have access to SDSs, and workers are effectively trained to respond to chemical exposure.4 Oral health professionals are required to comply with the directives outlined in the HCS, as there is a high risk of exposure to the chemicals used in the delivery of oral care, as well as during the cleaning and disinfection of the clinical setting and instruments.

CLASSIFICATION

The first change to the HCS relates to “hazard classification.” Now, definitions of hazards must provide specific criteria for classification of health and physical risks, as well as chemical mixtures.5,6 These criteria are intended to ensure that evaluations of hazardous chemical effects are consistent among all manufacturers—improving the accuracy of labels and SDSs. The US Environmental Protection Agency designates which chemicals are hazardous.7 But the initial identification, evaluation, and notification of chemical hazards are the manufacturer’s responsibility. This information is then disseminated to those parties who have purchased the chemical.5

LABELING

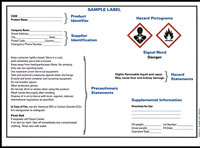

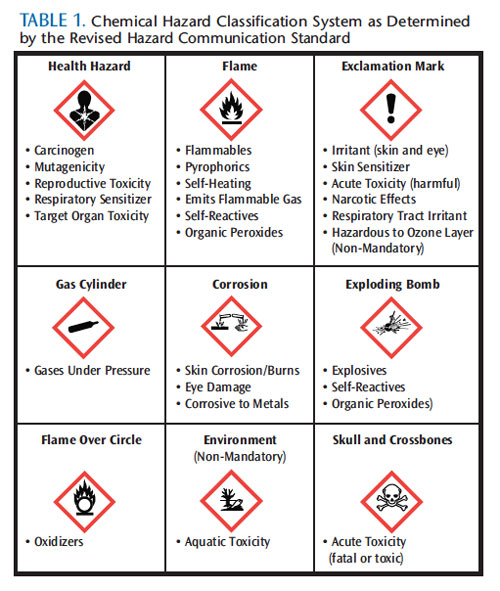

The second modification to the HCS is labeling. Manufacturers and importers are required to provide labels that will list the product identifier; include a hazard statement—or a short phrase that describes the nature of the hazard; use a harmonized signal word, such as “danger,” to alert users of the severity of the hazard; include a precautionary statement that explains how to handle, store, and dispose of the hazard; and a new pictogram that represents a specific message about the chemical.5,6 By June 1, 2015, all labels will appear like the example in Figure 1. Each pictogram, which consists of a symbol on a white background framed within a red border, represents a distinct hazard(s). The pictogram on the label is determined by the chemical hazard classification as seen in Table 1.5,8 This change will indirectly affect the oral health team and office staff, as employers are responsible for maintaining easy-to-read labels on containers. According to OSHA, employers have the option to create their own workplace labels with the required information per the revised HCS.9

SAFETY DATA SHEETS

Another major change to the HCS requires that manufacturers, importers, and distributors provide end-users with an SDS for each chemical. These updated information sheets appear in a new 16-point uniform format.5,9 Employers must obtain a specific SDS for each chemical present in the workplace, and it cannot be generic. For instance, if an office uses three different types of amalgam, three specific SDSs must be kept on file.5 Employers must ensure that SDSs are kept either as hard copies in a binder or in an electronic format that is consistently backed up and readily accessible to all employees.10 The new SDS format helps clinicians keep up-to-date with the sections that are necessary for follow-up in case of patient or provider exposure.9

TRAINING

The last major change to the HCS relates to training. A written hazard communication program is required in all workplaces where employees are exposed to hazardous chemicals. This plan describes how the HCS will be implemented. Employers must provide training to employees at initial hire, and/or when a new hazard is introduced in the workplace. As such, annual HCS training is recommended.5 As of December 1, 2013, OSHA will require employers to train dental team members on the new labeling and SDSs to facilitate recognition and understanding of these elements (Table 2).9

CONCLUSION

The revised HCS is intended to reduce confusion about chemical hazards in the workplace, facilitate safety training, and improve understanding of chemical use and its inherent risks.9 Although dental team members may minimize the danger of chemicals in their day-to-day practice of dentistry, risk does exist. Since 1970, OSHA’s mission has been to protect all American workers from hazards encountered in the workplace.11 The revised HCS is another example of this, and it is critically important that all dental team members recognize and mitigate the risk of chemical exposure in the workplace.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author would like to thank Nicholas Salomon for his assistance with the images for this article.

REFERENCES

- Kehe K, Reichl FX, Durner J, Walther U, Hickel R, Forth W. Cytotoxicity of dental composite components and mercury compounds in pulmonary cells. Biomaterials. 2001;22:317–22.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Globally Harmonized System for Classification and Labelling of Chemicals. Available at: www.epa.gov/oppfead1/international/globalharmon.htm. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- US Department of Labor. OSHA Revises Hazard Communication Standard. Available at: www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=NEWS_RELEASES&p_id=22038. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- US Department of Labor. What Is Hazard Communication? Available at: www.osha.gov/dsg/hazcom/whatishazcom.html. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- Miller CH, Palenik CJ. Infection Control and Management of Hazardous Materials for the Dental Team. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2013;246–263.

- US Department of Labor. Hazard Communication. Available at:www.osha.gov/dsg/hazcom/index.html. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- US Department of Labor. Hazard Communication Standard Labels. Available at: www.osha.gov/ Publications/ HazComm_ QuickCard_ Labels.html. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- US Department of Labor. Hazard Communication Standard Pictogram. Available at: www.osha.gov/ Publications/ HazComm_ QuickCard_Pictogram.html. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- US Department of Labor. Frequently Asked Questions: Hazard Communication (HAZCOM). Available at: www.osha.gov/html/faqhazcom.html. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- US Department of Labor. Hazard Communication Safety Data Sheets.Available at: www.osha.gov/ Publications/ HazComm_ QuickCard_SafetyData.html. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- US Department of Labor. All About OSHA. Available at: www.osha.gov/Publications/3302-06N-2006-English.html. Accessed November 25, 2013.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2013;11(12):26,28–29.