Electronic Cigarette Use Among Youth and Adolescents

Oral health professionals are on the frontline of helping youth avoid or quit e-cigarette use.

This course was published in the June/July 2024 issue and expires July 2027. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 158

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS).

- Identify systemic and oral health implications associated with electronic cigarette use.

- Recommend tobacco cessation modalities for youth and adolescent populations.

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) heat a liquid to create an aerosol that is inhaled by the user. The liquid contains nicotine and other toxic chemicals. Although ENDS do not contain tobacco, they are still considered tobacco products because nicotine is derived from tobacco. The most common ENDS are electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and vape pens.

Electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS) are another type of e-cigarette similar to ENDS but they do not contain nicotine. E-cigarettes claiming to be nicotine-free still typically contain trace amounts of nicotine.1 Although ENDS and ENNDS may not contain tobacco, harmful long-term health implications remain prevalent.

E-cigarettes were first introduced in 2003 as an alternative to conventional smoking. Many smokers report trying e-cigarettes in an effort to quit or reduce cigarette use.2 However, e-cigarettes do not have approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as safe and effective cessation aids.3 Additionally, many cigarette smokers who use ENDS as a smoking cessation aid end up using both products.2

Nearly 15% of US adults have reported using an e-cigarette, while approximately 3% said they were current e-cigarette users.4 Even more alarming, 20% of high school students and 5% of middle school students currently use e-cigarettes—making e-cigarettes the most used tobacco product among US youth.5

E-Cigarette Devices

E-cigarettes are battery-operated devices that heat nicotine, flavorings, and other chemicals to produce an inhalable aerosol.6,7 Although designs vary, all devices contain the following components: a cartridge, heating coil, power source, and a mouthpiece.6 Users inhale from the mouthpiece while the coil heats to create an aerosol from the cartridge containing the liquid solution. Devices may be refillable for repeatable use, or the device itself can be a disposable one-time tank use. Approximately 14 “puffs” is equal to one cigarette; however, smoking style, coil resistance, and individual usage can impact this calculation.8

The liquid solution for refillable units typically cost between $10 and $30 per cartridge. The average price of a refillable e-cigarette unit is $19.11 and $9.80 for disposable e-cigarettes; this is in comparison to $5.86 for a pack of cigarettes.9 Research suggests that increasing prices of disposable e-cigarettes, reusable e-cigarettes, and cigarettes reduces sales of the products.9

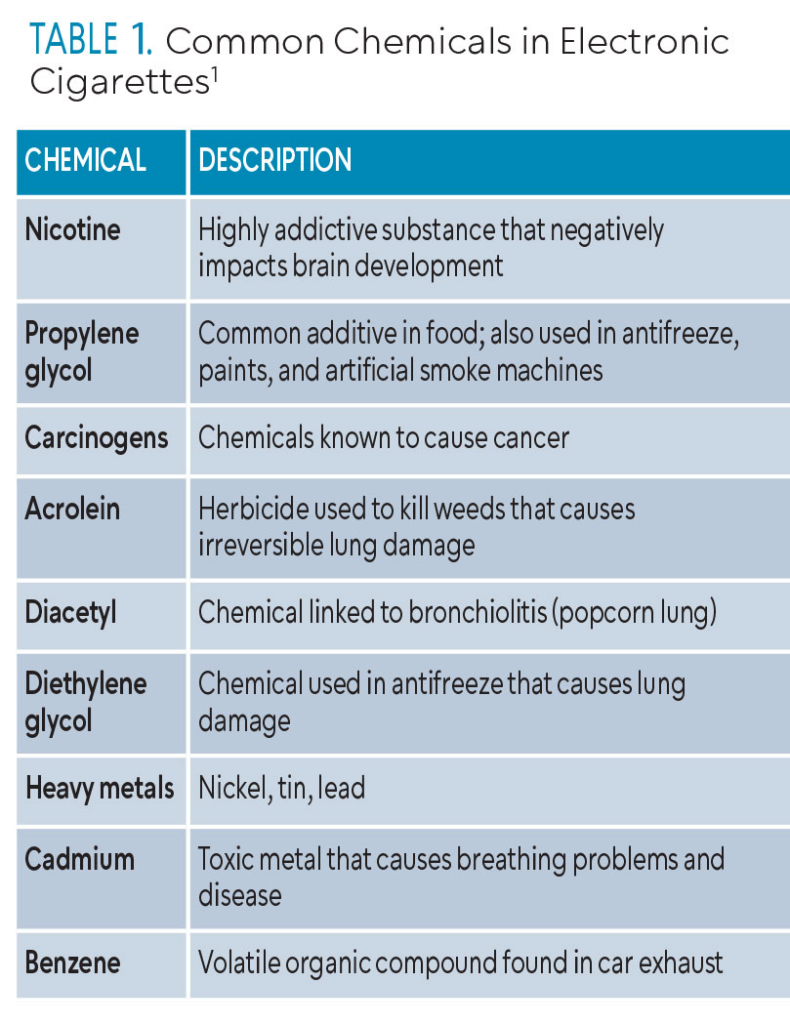

The main ingredients of the liquid in the e-cigarette devices are nicotine, propylene glycol, and flavoring. A wide variety of chemical components are contained in the cartridges, refill solutions, and aerosols of e-cigarettes. Kucharska et al10 identified more than 100 different chemicals in 50 brands of liquids. Table 1 lists some common substances identified in e-cigarette liquids and aerosols. The FDA requires companies to provide all chemistry and toxicology data, including substances the liquid and the aerosol generates.

A highly addictive stimulant drug, nicotine is the main psychoactive ingredient in tobacco products. The body quickly absorbs nicotine into the bloodstream so it can reach the brain. Nicotine levels peak quickly after entering the body, so the feelings of reward are short-lived.

Although ENDS do not contain dried tobacco leaves, they still contain nicotine. The nicotine content of e-cigarettes typically varies between 3 and 36 milligrams (mg)/milliliter (ml) with an average of 10 to 12 mg of nicotine.11,12 An adult cohort study comparing cigarette users to e-cigarette users revealed that e-cigarette users had higher urine concentrations of nicotine.13

![]() Oral and Systemic Health Considerations

Oral and Systemic Health Considerations

Nicotine poses various health risks, adversely affecting numerous bodily systems, with both immediate and long-term consequences. Some common side effects include but are not limited to headaches, abnormal sleep disturbances, increased clotting and blood pressure, tachycardia, cancer, joint pain, diarrhea, nausea, and xerostomia.14 Nicotine may also contribute to the hardening of the arterial walls, which may lead to a myocardial infarction.14

The hallmark symptoms of nicotine withdrawal include anxiety, depression, irritation, memory issues, concentration issues, tremors, and headaches.15 Furthermore, nicotine can interrupt the development of the adolescent brain since the brain is not considered fully developed until age 25. Using nicotine in adolescence can harm the parts of the brain that control attention, learning, mood, and impulse control.15

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recently investigated hospitalizations due to the use of ENDS. Individuals present with symptoms of shortness of breath, cough, and chest pain after the use of ENDS.16 The condition is referred to as e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury (EVALI). By February 2020, the CDC had recorded more than 2,800 hospitalizations due to EVALI along with 68 deaths.16 EVALI has been linked to vitamin E acetate, which is a synthetic form of vitamin E found in some vaping products.16 Because long-term data are lacking, the prognosis for those affected remains uncertain.

The respiratory cancer risk from the metals found in e-cigarettes varies depending on the ingredients used. Research shows that some aerosols exceed the acceptable range for cancer risk.17 Because many individuals use both e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes, it may be difficult to determine the main etiology of oral lesions.18 Strategies aimed at creating liquid composition consistency among companies are needed to better understand the short-term and long-term health implications.

Tobacco smoking is a major risk factor for the development of periodontitis.19 Unfortunately, few studies specifically examine the direct relationship between e-cigarette use and periodontitis. Most studies focus on the potential health risks of e-cigarettes compared to traditional cigarettes. However, e-cigarettes deliver nicotine, which has vasoconstrictive properties that can reduce blood flow to the gingival tissues.20 Additionally, the aerosol produced by e-cigarettes contains harmful chemicals that can irritate the oral tissues and potentially contribute to inflammation.21 Nicotine can also affect the immune system’s response to infection and inflammation, subsequently weakening the body’s ability to fight periodontal infections.20

This phenomenon could also influence the success rates of dental implants. Recent research has identified a rise in radiographic bone loss surrounding implants in individuals who use e-cigarettes.22 E-cigarette users also exhibit an increased volume of peri-implant sulcular fluid and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory markers.22 More comprehensive and long-term studies are needed.

Individuals who engage in e-cigarette use may also be more susceptible to dental caries due to several factors. First, the chemicals found in the vapor can contribute to the direct formation of biofilm and increase microbial adhesion on the teeth, fostering an environment conducive to caries.23 The components of e-cigarette liquids also typically contain sucrose, which can also increase biofilm formation and enamel demineralization.23,24 Furthermore, the acidic nature of some e-cigarette liquids, with a pH often below 5.5, raises concerns about erosive potential.24

Smoking Epidemic in Youth Populations

In 2009, the US Congress passed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which gives the FDA authority to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of tobacco products.25 Under this act, the FDA gained immediate authority to regulate cigarettes, cigarette tobacco, roll-your-own tobacco, and smokeless tobacco. FDA’s regulatory authority of ENDS, cigars, pipe tobacco, nicotine gels, and hookah tobacco did not take effect until 2016.

Under the Tobacco Control Act, the FDA restricted tobacco products marketing and sales to individuals 21 years and younger; however, marketing restrictions do not go beyond the avoidance of misleading claims. In fact, youth-appealing e-cigarette advertisements are on the rise by highlighting modernity, social status, and celebrity use.26,27 Primary sources for e-cigarette advertisements are local convenient stores, television, magazines, and social media.28 Banning advertising and promotion of tobacco and nicotine products has been shown to decrease use among adolescents.29

The control of tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, requires a comprehensive understanding of why youth populations are drawn to their use. Common reasons are curiosity, peer influences, and ability to use anywhere.30 Further youth-specific reasons are that e-cigarettes have appealing flavors, are easy to hide, are less expensive than traditional cigarettes, and do not smell like cigarettes.30

Prevention and Control of Youth Smoking

The earlier the age of smoking initiation during adolescence, the higher the risk of nicotine dependence and failure of smoking cessation later in life.31 The most effective tobacco control methods include school-based prevention programs and youth restrictive-access programs.2 School-based prevention programs have demonstrated short-term reduction of youth smoking but have controversial long-term effectiveness.

Implementing smoke-free environments can decrease the likelihood that adolescents will be smokers and increase the odds they will stop smoking if they have started experimenting.2 Smoke-free environments act as a preventive measure against the initiation of smoking among adolescents by shaping social norms, limiting access, reducing visibility of smoking, and providing educational resources about the risks associated with tobacco use.2

Concern about the effects of second-hand smoke on nonsmokers may provide a more powerful cessation message for youth than concern about the actual side effects of smoking.32 Secondhand aerosol from e-cigarettes contains nicotine, ultrafine particles, and concentrations of toxins that are known to cause cancer.33 Exposure to secondhand aerosols from e-cigarettes is associated with increased risk of bronchitis symptoms and shortness of breath among young adults, especially among nonusers.33

An experimental mice study found that indirect exposure to e-cigarette aerosols during the neonatal developmental period can impact weight, result in diminished alveolar cell proliferation, and impair lung growth.34 Nevertheless, further studies are needed to confirm the harmful effects of e-cigarette aerosols.

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) can help individuals overcome withdrawal symptoms and cravings, which are major barriers to successful cessation. There are five FDA-approved forms of NRT: patch, gum, nasal spray, inhalers, and lozenges.35 The patch, gum, and lozenge can be purchased over the counter, while the nasal spray and inhaler require a prescription. For best results, patients should be advised to pair a long-acting form of NRT (eg, nicotine patch) with a shorter-acting form (eg, gum, lozenge, spray, or inhaler).35

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) can help individuals overcome withdrawal symptoms and cravings, which are major barriers to successful cessation. There are five FDA-approved forms of NRT: patch, gum, nasal spray, inhalers, and lozenges.35 The patch, gum, and lozenge can be purchased over the counter, while the nasal spray and inhaler require a prescription. For best results, patients should be advised to pair a long-acting form of NRT (eg, nicotine patch) with a shorter-acting form (eg, gum, lozenge, spray, or inhaler).35

NRT should not be used if the individual is still using a nicotine product. Although NRT is considered safe for healthy adults, the FDA has not approved NRT for those younger than 18.35 Regardless, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends off-label NRT for youth who are moderately or severely addicted to nicotine because NRT is considered safer than continued cigarette and/or e-cigarette use.36 Youth younger than age 18 need a prescription from a healthcare provider to access all forms of NRT.

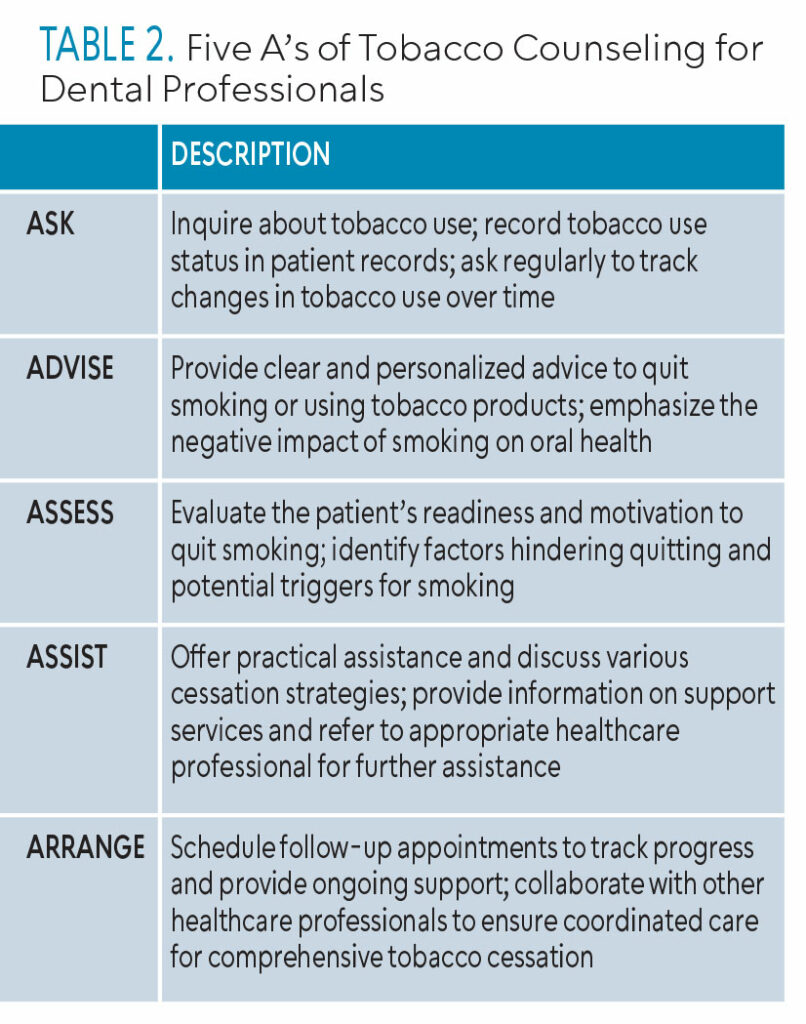

The increase in e-cigarette use coupled with emerging health hazards proves a significant need for intervention from healthcare providers. The 5 A’s — Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange — need to be implemented in cessation techniques for adult and youth populations alike. Using the 5 A’s allows for the healthcare provider to get a better understanding of patients and their readiness for change (Table 2). The Current Dental Terminology (CDT) includes D1320 tobacco counseling and intervention services, which aid in the control and prevention of oral disease. The CDT D1320 aligns well with the 5 A’s framework, allowing dental professionals to systematically address tobacco use, offer support, and encourage patients to quit.

Allied dental and advanced dental education programs have made great strides toward the inclusion of tobacco education into curriculum in recent years. Unfortunately, dental education programs provide only basic knowledge-based curriculum that rarely incorporates more effective, behavior-based components.37 Subsequently, dental professionals lack confidence in their role of supporting smoking cessation. Additionally, lack of time in the schedule and low reimbursement for tobacco cessation services prevents professionals from implementing effective programs.38 The majority of dental hygienists feel their efforts could assist patients in smoking cessation, but do not make cessation a priority during treatment planning or implementation.38

![]() Conclusion

Conclusion

As e-cigarette use has only become a prevalent epidemic in the last decade, future research is needed to confirm the long-term effects. Regardless, oral health professionals should receive adequate training to confidently address addiction and keep up to date on cessation resources.

References

- American Lung Association. What’s in an e-cigarette? ALA. November 17, 2022. Available at: https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/e-cigarettes-vaping/whats-in-an-e-cigarette. Accessed September 7, 2023.

- Kaplan B, Galiatsatos P, Breland A, Eissenberg T, Cohen JE. Effectiveness of ENDS, NRT and medication for smoking cessation among cigarette-only users: a longitudinal analysis of PATH Study wave 3 (2015-2016) and 4 (2016-2017), adult data. Tob Control. 2023;32(3):302-307.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “Facts about E-cigarettes.” FDA. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/rumor-control/facts-about-e-cigarettes#:~:text=Fact%3A%20To%20date%2C%20no%20e,as%20a%20smoking%20cessation%20device. Accessed November 13th, 2023.

- Villarroel MA, Cha AE, Vahratian A. Electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults, 2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;(365):1-8

- Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Cullen KA, King BA. E-cigarette use among middle and high school students – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1310-1312.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Vaping devices (electronic cigarettes) drugfacts. NIDA. January 8, 2020. Available at: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/vaping-devices-electronic-cigarettes. Accessed May 10, 2023.

- Zhu S-H, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: Implications for product regulation. Tob Control. 2014;23 Suppl 3:iii3-iii9.

- DeVito EE, Krishnan-Sarin S. E-cigarettes: Impact of e-liquid components and device characteristics on nicotine exposure. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(4):438-459.

- Yao T, Sung HY, Huang J, Chu L, St Helen G, Max W. The impact of e-cigarette and cigarette prices on e-cigarette and cigarette sales in California. Prev Med Rep. 2020;20:101244. Published 2020 Nov 6. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101244

- Kucharska M, Wesołowski W, Czerczak S, Soćko R. Badanie składu płynów do e-papierosów – deklaracje producenta a stan rzeczywisty w wybranej serii wyrobów [Testing of the composition of e-cigarette liquids – Manufacturer-declared vs. true contents in a selected series of products]. Med Pr. 2016;67(2):239-253.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Eaton DL, Kwan LY, Stratton K, et al., eds. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); January 23, 2018.

- Walley SC, Wilson KM, Winickoff JP, et al. a public health crisis: Electronic cigarettes, vape, and JUUL. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6):e20182741.

- Goniewicz ML, Smith DM, Edwards KC, et al. Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e185937.

- Mishra A, Chaturvedi P, Datta S, Sinukumar S, Joshi P, Garg A. Harmful effects of nicotine. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2015;36(1):24-31.

- Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151.

- Rebuli ME, Rose JJ, Noël A, et al. The e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury epidemic: pathogenesis, management, and future directions: An official American thoracic society workshop report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(1):1-17.

- Lin HC, Buu A, Su WC. Disposable e-cigarettes and associated health risks: An experimental study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10633. Published 2022 Aug 26.

- Sultan AS, Jessri M, Farah CS. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: Oral health implications and oral cancer risk. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021;50(3):316-322. doi:10.1111/jop.12810

- Chaffee BW, Couch ET, Vora MV, Holliday RS. Oral and periodontal implications of tobacco and nicotine products. Periodontol 2000. 2021;87(1):241-253. doi:10.1111/prd.12395

- Mahmoudzadeh L, Abtahi Froushani SM, Ajami M, Mahmoudzadeh M. Effect of nicotine on immune system function. Adv Pharm Bull. 2023;13(1):69-78. doi:10.34172/apb.2023.008

- Thomas SC, Xu F, Pushalkar S, Lin Z, Thakor N, Vardhan M, Flaminio Z, Khodadadi-Jamayran A, Vasconcelos R, Akapo A, Queiroz E, Bederoff M, Janal MN, Guo Y, Aguallo D, Gordon T, Corby PM, Kamer AR, Li X, Saxena D. Electronic cigarette use promotes a unique periodontal microbiome. mBio. 2022 Feb 22;13(1):e0007522.

- Baniulyte G, Ali K. Do e-cigarettes have a part to play in peri-implant diseases? Evid Based Dent. 2023;24(1):7-8. doi:10.1038/s41432-023-00864-w

- Rouabhia M, Semlali A. Electronic cigarette vapor increases Streptococcus mutans growth, adhesion, biofilm formation, and expression of the biofilm-associated genes. Oral Dis. 2021;27(3):639-647. doi:10.1111/odi.13564

- Irusa KF, Finkelman M, Magnuson B, Donovan T, Eisen SE. A comparison of the caries risk between patients who use vapes or electronic cigarettes and those who do not: A cross-sectional study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2022;153(12):1179-1183. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2022.09.013

- Food and Drug Administration. Family smoking prevention and tobacco control act. FDA. June 3, 2020. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/rules-regulations-and-guidance/family-smoking-prevention-and-tobacco-control-act-overview. Accessed May 9, 2023.

- Padon AA, Maloney EK, Cappella JN. Youth-targeted e-cigarette marketing in the US. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(1):95-101.

- Chu KH, Sidhu AK, Valente TW. Electronic cigarette marketing online: a multi-site, multi-product comparison. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2015; 1(2):e11

- Simon P, Camenga DR, Morean ME, et al. Socioeconomic status and adolescent e-cigarette use: The mediating role of e-cigarette advertisement exposure. Prev Med. 2018;112:193-198. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.04.019

- WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Nicksic NE, Snell LM, Barnes AJ. Reasons to use e-cigarettes among adults and youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Addict Behav. 2019;93:93-99.

- Lydon DM, Wilson SJ, Child A, Geier CF. Adolescent brain maturation and smoking: what we know and where we’re headed. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;45:323-342.

- Kalkhoran S, Neilands TB, Ling PM. Secondhand smoke exposure and smoking behavior among young adult bar patrons. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):2048-2055.

- Islam T, Braymiller J, Eckel SP, et al. Secondhand nicotine vaping at home and respiratory symptoms in young adults. Thorax. 2022;77(7):663-668.

- McGrath-Morrow SA, Hayashi M, Aherrera A, et al. The effects of electronic cigarette emissions on systemic cotinine levels, weight and postnatal lung growth in neonatal mice. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0118344. Published 2015 Feb 23.

- Wadgave U, Nagesh L. Nicotine replacement therapy: An overview. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2016;10(3):425-435.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Nicotine replacement therapy and adolescent patients. AAP. November 16, 2022. Available at: https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/tobacco-control-and-prevention/youth-tobacco-cessation/nicotine-replacement-therapy-and-adolescent-patients/. Accessed May 11, 2023.

- Ramseier CA, Christen A, McGowan J, et al. Tobacco use prevention and cessation in dental and dental hygiene undergraduate education. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2006;4(1):49-60

- Goel D, Chaudhary PK, Khan A, et al. Acquaintance and Approach in the Direction of Tobacco Cessation Among Dental Practitioners-A Systematic Review. Int J Prev Med. 2020;11:167. Published 2020 Oct 5.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June/July 2024; 22(4):42-45