DIGITAL VISION./PHOTODISC/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

DIGITAL VISION./PHOTODISC/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Effects of Mastication on Cognitive Health

Research demonstrates that masticatory disfunction may also be a risk factor for dementia.

This course was published in the September 2019 issue and expires September 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the prevalence of dementia.

- Explain the role of mastication in oral and systemic health.

- Discuss the correlation between masticatory dysfunction and dementia.

- Describe the role that dental hygienists play in helping patients maintain their masticatory function.

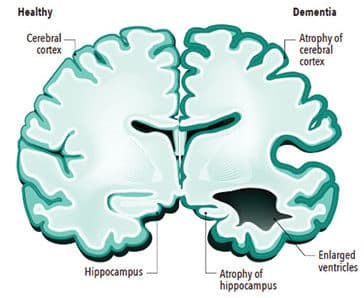

With billions of neurons carrying information through electrical and chemical signals, the human brain is an amazing organ. When healthy, these neurons successfully send messages from the brain to different parts of the body with seeming ease. However, dementia interferes with these communicating neurons, leading to reduced function and eventually cell death.1 Figure 1 (page 37) shows a comparison between a healthy brain and one that is impacted by dementia.

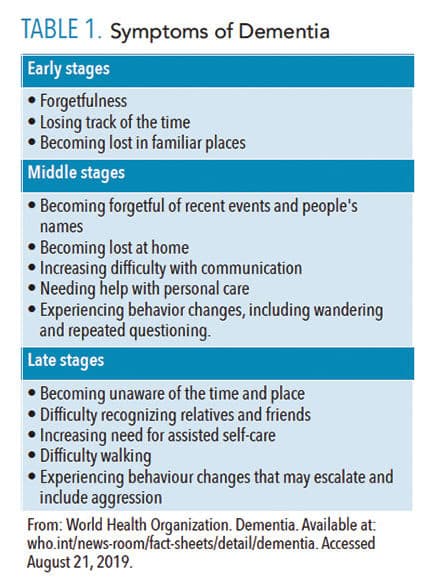

A neurocognitive disorder, dementia is a chronic and/or progressive syndrome associated with memory loss, disorientation, personality changes, and loss of motor functions. These changes impair the ability to perform activities of daily living, resulting in loss of autonomy.2 Table 1 lists the symptoms of dementia from early to late stages.

The prevalence of dementia increases with age; however, it is not an unavoidable part of aging. With a growing older adult population, the number of individuals experiencing dementia is expected to increase.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 50 million people are living with dementia worldwide, with more than half of those residing in low- to middle-income countries, and it predicts that dementia will affect 82 million people by 2030 and 152 million by 2050.4 Research is underway to identify modifiable risk factors that may aid in the prevention of dementia and inhibit the progression of this cognitive impairment.5

Dementia encompasses a variety of forms, with Alzheimer disease being the most common. The WHO estimates that Alzheimer disease comprises 60% to 70% of dementia cases. Vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia are other types.4

Several risk factors for dementia have been established, including age, genetics, race/ethnicity, with African-Americans at higher risk than whites, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, depression, obesity, inactivity, lack of social engagements, traumatic brain injury, and hearing loss.6,7 Based on newly found correlations, masticatory disfunction may also be a risk factor for dementia.3 Individuals may experience masticatory dysfunction via tooth loss, masticatory muscle weakness, or occlusal disharmony.8

IMPORTANCE OF MASTICATION

Mastication is not only an important aspect of oral health and function, it is also related to memory.9 Research shows that masticatory dysfunction related to tooth loss, inadequate prosthesis, and weak mastication muscles is associated with the worsening of dementia.10 In 1986, a 30-year ongoing longitudinal study (the nun study) was begun by David Snowdon, PhD. The study followed a group of nuns over time and provided investigators with data regarding Alzheimer disease. Using the information provided by the nun study, Stein et al11 found evidence that related masticatory dysfunction to cognitive decline. This pioneering investigation was the first to find that the number of missing teeth was associated with an increased risk of dementia.

Neuroimaging research has determined that mastication not only affects regional brain activity but also activates connectivity with associated networks.12 The brain-stomatognathic axis is a communication network between the cortical and subcortical structures in the brain, teeth, and periodontium.10 Adequate masticatory function offers sensory input from the teeth and oral cavity transmitted through the trigeminal nerve to the hippocampus. A literature review by Chen et al13 found that in studies of subjects with normal dentition and those who were edentulous, normal activations of the basal nucleus and cerebellum occurred in patients with normal dentition, whereas no activations were found in edentulous patients.

Memory and learning are significantly impaired by masticatory dysfunction caused by tooth loss, periodontal diseases, or soft diet.7,11 The hippocampus is the area of the brain that controls learning and memory, specifically episodic memory. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor encourage proliferation of neuronal cells, differentiation and survival of the neuronal cells, and synapse formation in the hippocampus. Masticatory dysfunction due to weakened muscles of mastication and/or tooth loss leads to inadequate stimulation of the central nervous system. This results in hippocampal atrophy due to inactivity.9

The number of teeth, median occlusion contact area, and bite force are lower for older adults with cognitive impairment compared with those who have normal cognitive abilities.11,14 Mastication also affects general health, which influences cerebellar functions and improves hippocampus-dependent cognition.13

STRESS HORMONES AND MASTICATION

The human body responds physiologically and psychologically to chronic stress, which can lead to disease. A stressful incident activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and, in turn, releases steroid hormones in an effort to maintain homeostasis. In addition to the activation of the HPA, the body also releases adrenaline/noradrenaline as the sympathetic nervous system is stimulated. Chronic elevated levels of these hormones create a stressed condition that leads to breakdown in both physical and psychological health systems, as well as cognitive impairment. It is thought that activation of HPA directly impairs prospective memory.15 Prospective memory is the intention to complete a task in the near future. For example, remembering to stop by the post office on the way home from work.

Research shows that mastication or chewing can be used as a coping behavior when exposed to stressors because mastication during taxing experiences depresses activation of the HPA axis. In one study, animals that were restrained showed a lower level of plasma corticosteroids and HPA axis-related responses when given a wooden stick to chew.16 Another study investigated the effects of gum chewing to decrease stress and improve focus and memory.17 Moderate gum chewing intensity increased heart rate and cerebral blood flow through the middle cerebral artery. It was also noted that gum chewing activated the right prefrontal cortex, improving executive functions such as attention and working memory.17

Oral health professionals can educate patients on the importance of maintaining dentition and chewing sugar-free gum (in moderation) to improve memory and focus, and to decrease activation of the HPA. Excessive gum chewing, however, can exacerbate temporomandibular joint disorders, so patients should be counseled on what constitutes moderate gum chewing.18

NUTRITION

A positive correlation exists between decreased mastication and modified dietary intake. Dietary modifications include avoidance of difficult-to-chew foods such as meats, vegetables, and solid fruits, and/or physical alterations made to food selections. Poor mastication can induce gastrointestinal disorders in older adults because a proper masticatory process decreases the digestion load placed on the stomach and aids in nutrient absorption. Dietary selections made to ease chewing can cause nutrient intake imbalance, thereby reducing dietary quality.

In a Korean study, subjects with chewing difficulty had diets deficient in vitamin C and potassium, while consuming fewer calories and nutrients, such as sodium, riboflavin, niacin, calcium, and vitamin A than subjects with normal masticatory function.19 Individuals with fewer teeth are at increased risk for developing nutritional deficiencies, especially in B vitamins, which contribute to cognitive decline and dementia.2 Utsugi et al20 found the consumption of a soft diet vs a hard diet in adult mice was related to cognitive decline. Mice fed soft diets had less neurogenesis, similar to mice with impaired masticatory function, due to lack of stimulation to the hippocampus.

REPLACEMENT OF TEETH

Dentures are a common solution for edentulous patients, and their use impacts masticatory function. Kamiya et al20 evaluated prefrontal activity in patients with tooth loss, patients wearing a removable partial denture, and young patients with full, natural dentition. Masticatory performance, occlusal force, and masticatory muscle were evaluated in each sample. To measure brain activity in the prefrontal cortex, functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) was used to measure the amount of oxygenated-hemoglobin during chewing. Results showed wearing a denture significantly improved the masticatory score and occlusal force. The results from the fNIRS indicated that subjects with dentures experienced such significant gains in prefrontal activation that there was little difference in chewing performance between the older patients with tooth loss and the young, healthy individuals. This showed a benefit of replacing teeth with a removable partial denture in order to preserve current brain status and prevent cognitive decline.21

Implant therapy, including single-tooth implants or implant-supported dentures, is a common treatment for tooth loss. A literature review by Prithviraj et al22 evaluated multple studies regarding conventional dentures, implant-supported overdentures, and implant-supported fixed dentures. Throughout each study, the overarching consensus was that natural dentition provided the best masticatory performance. Fixed and removable implant dentures had similar results of a median level of masticatory performance, and conventional dentures had the lowest level. When chewing was assessed from the patient perspective, patients preferred removable implant dentures over fixed implant dentures due to increased ease of cleaning.22

CALL TO ACTION

Masticatory ability is not associated with aging and does not decline with age as long as posterior occlusal contact is maintained.23 For oral health professionals, the first line of defense against dementia is to assist paients in maintaining their natural dentition for as long as possible. Chairside education, tailored to each patient, regarding different risks for tooth loss can help preserve their dentition.24

Patients with missing teeth or who are edentulous should be advised to wear prosthetics not only for esthetics, but to restore masticatory performance to enhance nutritional intake, assist with stress reduction and affected immune response, activate neurogenesis, enhance hippocampal stimulation, and improve cerebral blood flow. This ultimately influences cognitive function and deters the development of dementia.

Routine dental visits to evaluate patients’ oral health conditions are an integral step in slowing or eliminating the tooth-loss process. These examinations should include oral cancer screenings; complete periodontal evaluation, including radiographs to assess alveolar bone resorption, implant placement, and condition; chairside masticatory assessment; diet evaluation; and stability and retention of prosthetics. Prosthetics need to be examined so the condition of soft tissue and/or teeth supporting the prosthesis can be documented. Increasing the public’s awareness of the oral-systemic health link and appropriate oral health strategies may help decrease the prevalence of dementia.24

CONCLUSION

Research demonstrates that proper masticatory function may play a role in preventing or delaying the onset of dementia. Masticatory dysfunction leads to hyperactivity of the HPA and increase in stress hormones, which can lead to cognitive decline.8 This association between masticatory dysfunction and cognitive decline is well documented, but further research is necessary, particularly studies conducted on human subjects. Dementia is also a multifactorial disease with a complex etiology. Dental hygienists play an important role in the education and encouragement of patients to maintain their existing dentition and care for their prostheses, which may, ultimately, reduce their risk for dementia.

REFERENCES

- National Institute on Aging. What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease? Available at: nia.nih.gov/health/what-happens-brain-alzheimers-disease. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- SeraJ Z, Al-Najjar D, Akl M, et al. The effect of number of teeth and chewing ability on cognitive function of elderly in UAE: A pilot study. Int J Dent. 2017;2017:5732748.

- Watanabe Y, Hirano H, Matsushita K. How masticatory function and periodontal disease relate to senile dementia. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2015;51(1):34–40.

- World Health Organization. Dementia: A Public Health Priority. Available at: who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- Oh B, Han D, Han K, et al. Association between residual teeth number in later life and incidence of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:48.

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–2734.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dementia. Available at: cdc.gov/aging/dementia/index.html. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- Azuma K, Zhou Q, Niwa M, Kubo K. Association between mastication, the hippocampus, and the HPA axis: A comprehensive review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1687.

- Fukushima-Nakayama Y, Ono T, Hayashi M, et al. Reduced mastication impairs memory function. J Dent Res. 2017;96:1058–1066.

- Lin C. Revisiting the link between cognitive decline and masticatory dysfunction. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:5.

- Stein PS, Desrosiers M, Donegan SJ, Yepes JF, Kryscio RJ. Tooth loss, dementia and nueropathology in the nun study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(10):1314–1322.

- Lin CS, Wu CY, Wu SY, Lin HH, Cheng DH, Lo WL. Age-related differences in functional brain connectivity of mastication. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:82.

- Chen H, Iinuma M, Onozuka M, Kubo K. Chewing maintains hippocampus-dependent cognitive function. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:502–509.

- Campos CH, Ribeiro GR, Costa JLR, Rodrigues Garcia RCM. Correlation of cognitive and masticatory function in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:573–578.

- Ballhausen N, Kliegel M, Rimmele U. Stress and prospective memory: what is the role of cortisol? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2019;161:169–174.

- Kubo K, Iinuma M, Chen H. Mastication as a stress-coping behavior. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:876409.

- Douma JG, Volkers KM, Vuijk PJ, Scherder EJ. The effects of video observation of chewing during lunch on masticatory ability, food intake, cognition, activities of daily living, depression, and quality of life in older adults with dementia: a study protocol of an adjusted randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:37.

- Mapelli A, Machado B, Giglio L, Sforza C, Felicio C. Reorganization of muscle activity in patients with chronic temporomandibular disorders. Arch Oral Biol. 2016;72:164–171.

- Kwon SH, Park HR, Lee YM, et al. Difference in food and nutrient intakes in Korean elderly people according to chewing difficulty: Using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013 (6th). Nutr Res Pract. 2017;11:139–146.

- Utsugi C, Miyazono S, Osada K, et al. Hard-diet feeding recovers neurogenesis in the subventricular zone and olfactory functions of mice impaired by soft-diet feeding. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97309.

- Kamiya K, Narita N, Iwaki S. Improved prefrontal activity and chewing performance as function of wearing denture in partially edentulous elderly individuals: functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158070.

- PrithviraJ D, Madan V, Harshamayi P, Kumar C, Vashisht R. A comparison of masticatory efficiency in conventional dentures, implant retained or supported overdentures and implant supported fixed prostheses: a literature review. Journal of Dental Implants. 2014;4(2):153–157.

- Marito P, Pratama S, Utomo HPD, Koesmaningati H, Kusdhany LS. Masticatory ability assessments and related factors. Journal of International Dental and Medical Research. 2018;11(1):206-210.

- Taverna MV, Nguyen CA, Hicks BM. Oral hygiene and self-care in older adults with dementia. Generations. 2016;40(3):43–48.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2019;17(8):34,37–39.