Effective Implant Care

Follow these keys to successful implant assessment and maintenance.

The successful care of dental implants is based on patient-specific treatment and scientific evidence while also incorporating the clinician’s experience. The dental hygienist plays an important role in the assessment and management of dental implant patients. This role will continue to evolve as technology advances and the scope of implant dentistry broadens.

The dental hygienist’s role in implant care begins with helping to identify potential implant patients and continues throughout the life of the implant by identifying potential problems or complications. Dental hygienists also: educate and motivate throughout treatment; develop, assess, and adapt oral hygiene procedures; evaluate the implant (components, attachments, mobility, and retention); evaluate peri-implant tissue; probe; take radiographs; remove biofilm; recommend oral hygiene implements; and determine a patient-specific maintenance interval.1

BIOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

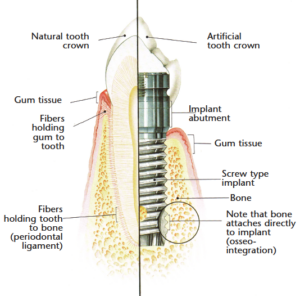

Understanding the biological differences between teeth and implants is imperative for the effective provision of implant maintenance care. A natural tooth has a firm connective tissue attachment to the bone composed of a mass of fibers, which are embedded into the cementum of the tooth (Figure 1).2 Dental implants also have this tissue attachment to the bone.2 Dental implants also have this tissue attachment to the bone.3 In the junctional epithelium, the natural tooth has fibers inserting into cementum whereas the dental implant has a weaker hemidesmosomal attachment. Consequently, when performing maintenance procedures around an implant, such as probing, this lack of strong tissue attachment creates an area that may be easily penetrated, allowing bacteria to enter.4 The lack of a true fibrous attachment makes implants more susceptible to inflammation and bone loss in the presence of plaque accumulation.5

PROBING

It is important to visually assess the health and tone of the peri-implant tissue. Routine probing is quite controversial. Generally it is not recommended when there are no symptoms of disease/pathology because of the increased susceptibility of the tissue and because aggressive pressure may create a false bleeding on probing response.6 However, individual patient need and clinician experience should be considered in each case. Since the sulcus around an implant is surgically created, abutment attachment and wound healing that deviate from normal sulcular depth may be related to tissue biotype.7 If there are symptoms of disease that cause probing to become necessary, a fixed reference point is recommended in order to eliminate inaccurate probing depths due to gingival hyperplasia and hypertrophy. It is often difficult to obtain accurate probing depths in dental implant patients because of prosthesis design, such as wide emergence profiles, ridge lap crown designs, and subgingival margins. Natural teeth can serve as a reservoir for bacteria so dental hygienists should avoid introducing bacteria from around the teeth into the sulcus around implants.8 The easiest way to avoid this transfer of bacteria is to probe or scale the dental

implants first.

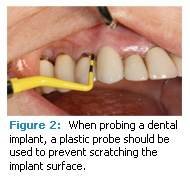

Probing should always be performed when bone loss or pathology is present, and it can help determine facial-lingual bone levels. Plastic probes should be used because they will not scratch or mar the titanium surfaces of implants (Figure 2). Rounded probes rather than ball tip probes may also provide greater patient comfort during probing.

Table 1. Important qualities to consider when choosing an instrument to use on patients with dental implants.

- Made from an implant friendly design, such as plastic

- Familiar design

- Autoclavable or disposable

- Rigidity to withstand scaling pressure without the risk of fracture or breakage

- Whether it leaves residue

- Blade dimensions that allow easy and atraumatic access to implant abutment angulations and tissue tightness

- Lightweight to avoid hand and wrist fatigue

- Cost effectiveness

RADIOGRAPHS

Determining which radiographs are most appropriate for implant patients is based on what the dental hygienist is trying to assess or diagnose. Several options are available, such as intraoral films (periapicals or bitewings) and extraoral images (panoramic or computerized axial tomography [CAT] scans). For potential implant candidates, a panoramic radiograph is the most appropriate image. The panoramic radiograph provides a visual roadmap to assist with treatment planning and patient education.

A CAT scan may be requested for more precise views of sinus, bone, and nerve anatomy, and when more complex treatment planning is required. Technology is advancing so rapidly that in-office digital scans are becoming more common. The comfort level of the dental hygienist, patient requirements, and availability of equipment are issues that need to be considered before determining which radiographs are necessary. If the patient is undergoing surgical treatment, the dentist may use periapical radiographs to check pilot drills and landmarks. Mesial and distal angulations can also be verified with intraoral radiographs. For patients in the restoration phase of treatment, radiographs may be used to check for complete seating of the transfer coping prior to taking impressions. Best practices include routinely checking complete abutment seating and restoration seating prior to patient dismissal. The radiograph of the final insertion will serve as a baseline for future radiographic comparison. The best radiograph for these procedures is typically the vertical bitewing because it offers the least variation in distortion while focusing on the implant-crestal bone interface.

During maintenance, the crestal bone level allows for the assessment of bone maintenance or bone loss. The vertical bitewing provides the most appropriate image of this area. The parallel technique provides a pinpoint view of the bone-tissue interface with low distortion. Nerves are not present when assessing implants and evaluating surrounding tissue so there is no need to watch for periapical pathology. Radiolucency around an implant will start from the crestal bone and proceed apically. If crestal bone loss is detected, the most apical portion of the bone loss must be captured in order to clearly see the implant-bone interface.

Patient comfort is important when taking radiographs of an edentulous patient who has a restored implant. Frequently these patients have developed anatomical changes, such as macroglossia, thinning of alveolar tissue, and atrophy of bone and muscle, that can make taking radiographs difficult and/or uncomfortable. Cushions, cotton rolls, and gauze pads can help relieve the pres- sure of impinging films or sensors. If the radiographic view is not hindered, it may be easier for patients with overdentures to keep them in their mouths in order to bite on the film holder. Patient position- ing with panoramic radiographs may also be a challenge if a patient needs to remove overdentures since a majority of facial support and accompanying exter- nal landmarks may disappear.

Table 2. Changes from baseline that indicate a need for further assessment.25

- Inflammation

- Bleeding

- Exudate

- Radiographic bone loss

- Restoration that needs replacement

- Decline of patient’s health status

- Mobility

- Increase in probing depth

- Patient complaint of pain

INSTRUMENT SELECTION

The longevity of any implant placement is dependent on proper tissue maintenance. As the use of dental implants grows, dental hygienists will see more complications and long-term maintenance challenges. Choosing the right instruments for dental implant care is critical to maintaining implant surfaces and avoiding tissue trauma.

Dental implants and the abutments on which restorations are placed are most often made of titanium. Titanium is a soft metal that is highly susceptible to scratches and surface alterations, which can become problematic during maintenance procedures. Research shows that stainless steel and titanium instruments and instruments with glass and graphite fillers can alter or scratch implant abutment surfaces9-16 and produce a rough, pitted surface that is ideal for harboring plaque and calculus.17 Rough surfaces are also more likely to harbor higher bacterial counts, which may contribute to the development of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis (see Table 3 for definitions).18,19 Metal sonic and ultrasonic scalers can also scratch and produce excessive heat, both of which can harm an implant and/or abutment.9

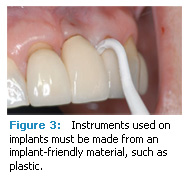

Dental instruments used on implants need to be made of an implant-friendly material, such as plastic, while offering the same basic features as a metal scaler or curet (Figure 3). Table 1 lists important instrument qualities to consider.20

Table 3. Glossary of Terms

Peri-implant mucositis: Reversible inflammatory reaction in the soft tissues surrounding a dental implant that can lead to bone loss.

Peri-implantitis: Inflammatory reaction in the hard and soft tissues surrounding a dental implant that results in bone loss.

Permucosal seal: Junctional epithelium that separates the connective tissues from the outside environment surrounding a dental implant.

Used with permission from ICOI’s Glossary of Implant Dentistry II.

Polishing after calculus removal with a rubber cup and nonabrasive toothpaste, fine prophy paste, and tin oxide will not alter titanium implant surfaces.12,15 Because of the implant’s lack of porosity, the adherence and tenacity of calculus around implants are generally less than around natural teeth. When removing accretions on an implant abutment and restoration, the dental hygienist should be careful not to rip or damage the permucosal seal (Table 3). When calculus is subgingival, the blade should be placed atraumatically under the deposit with careful instrumentation using exploratory strokes and light pressure in a coronal, semicircular direction. In addition to calculus, excess cement can also act as an irritant, which may contribute to bone loss. Thus, implant restorations should be assessed after seating to be sure all excess cement has been removed.

PATIENT EDUCATION

Self-care can make the difference between implant success and failure. If plaque is allowed to remain in the peri-implant site, tissue destruction may result. The dental hygienist needs to impart the importance of effective plaque removal as well as provide a patient-specific self-care routine. The routine should be adjusted as the patient moves through the different phases of implant care from post-surgical hygiene to ongoing implant maintenance.24

LONG-TERM MAINTENANCE

Dental hygienists need to note any changes from baseline because they are often early indicators of complications that require further evaluation and possible intervention or correction. Table 2 provides a list of changes that may indicate a problem with the implant.25

DOCUMENTATION

Implant success can be difficult to evaluate.7 The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) has a scale that can be used to evaluate an implant, categorize its health or disease, and then treat it accordingly (Table 4). Appropriate treatments may include taking radiographs more frequently, shortening the interval between recall visits, reduction of stresses, gingivoplasty, drug therapy (local or systemic), surgical revision, a change to the prosthesis or implant, or removal of the implant. Thorough documentation and communication are essential to providing care for the implant patient especially if a change is noted or treatment needs to be initiated. Ensuring the long-term success of dental implants requires a team effort with the dental hygienist serv- ing as a key member. The dental hygienist must continually review and adapt treatment protocols based on current research and patient needs in order to provide the best comprehensive care to dental implant patients.

REFERENCES

- Misch CE. Maintenance of dental implants: implant quality of health scale. In: Contemporary Implant Dentistry. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:1074.

- Gargiulio A, Wentz F, Orban B: Dimensions and relations of the dentogingival junction. J Periodontol. 1961;32:261-268.

- Berglundh T, Lindhe, J. Dimensions of the peri- implant mucosa. Biological width revisited. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:971-973.

- Misch CE. An implant is not a tooth: a comparison of periodontal indices. In: Contemporary Implant Dentistry. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:1064.

- Berglundh T, Lindhe J, Ericsson I, et al. The soft tissue barrier at implants and teeth. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1991;2:81-90.

- Gerber JA, Tan WC, Balmer TE, Salvi GE, Lang NP. Bleeding on probing and pocket probing depth in relation to probing pressure and mucosal health around oral implants. Clin Oral Impl Res. 2009;20:75-78.

- Misch CE, Perel M, Wang HL, et al. Implant success, survival, and failure: The ICOI Pisa Consensus Conference. Implant Dent. 2008:17;5-9.

- Apse P, Ellen RP, Overall CM, et al. Microbiota and crevicular fluid collagenase activity in the osseointegrated dental implant sulcus: a comparison of sites in edentulous and partially edentulous patients. J Periodontal Res. 1989;24:96-105.

- Hallmon W, Waldrop T, Meffert R, Wade B. A comparative study of the effects of metallic, nonmetallic, and sonic instrumentation on titanium abutment surfaces. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1996:11:96-100.

- Brookshire FV, Nagy WW, Dhuru VB, Ziebert GJ, Chada S. The qualitative effects of various types of hygiene instrumentation on commercially pure titanium and titanium alloy implant abutments: an in vitro and scanning electron microscope study. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;78:286-294.

- Rapley JW, Swan RH, Hallmon WW, Mills MP. The surface characteristics produced by various oral hygiene instruments and materials on titanium implant abutments. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1990;5:47-52.

- Meschenmoser A, d’Hoedt B, Meyle J, et al. Effects of various hygiene procedures on the surface characteristics of titanium abutments. J Periodontol. 1996:229-235.

- Mengel R, Buns CE, Mengel C, Flores-de-Jacoby L. An in vitro study of the treatment of implant surfaces with different instruments. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1998;13:91-96.

- Augthun M, Tinschert J, Huber A. In vitro studies on the effect of cleaning methods on different implant surfaces. J Periodontol. 1998;69:857-864.

- Matarasso S, Quaremba G, Coraggio F, et al. Maintenance of implants: an in vitro study of titanium implant surface modifications subsequent to the application of different prophylaxis procedures. Clin Oral Impl Res. 1996:7:64-72.

- Duarte P, Reis AF, deFreitas PM, Ota-Tsuzuki C. Bacterial adhesion on smooth and rough titanium surfaces after treatment with different instruments. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1824-1832.

- Dental implants in periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1934-1942.

- Amoroso PF, Adams RJ, Waters MG, Williams DW. Titanium surface modification and its effect on the adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis: an in vitro study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:633-637.

- Bollen CM, Papaioanno W, Van Eldere J, et al. The influence of abutment surface roughness on plaque accumulation and peri-implant mucositis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;7:201-111.

- Ramaglia L, di Lauro AE, Morgese F, Squillace A. Profilometric and standard error of the mean analysis of rough implant surfaces treated with different instrumentations. Implant Dent. 2006;15:77-82.

- Probster L, Lin W. Effects of fluoride prophylactic agents on titanium surfaces. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992;2;7:390-394.

- Granier Sison S. Implant maintenance and the dental hygienist. Access. 2003;May-June(Spec Suppl):2.

- Krauser J, Terracciano-Mortilla LD, LaBeau J. Hygiene and soft tissue management: two perspectives. In: Babbush CA. Dental Implants The Art and Science. 2nd ed. Maryland Heights, Mo: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:493.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2010; 8(9): 30-32, 34.