Detect Tooth Abnormalities

Early recognition of these oral health problems may help improve treatment outcomes.

Tooth abnormalities can affect the shape, number, size, and structure of teeth. The etiology of tooth abnormalities is either related to genetics or environmental factors. Ameloblasts, the cells responsible for laying down enamel, are extremely sensitive to external stimuli,1 so alterations in tooth structure can result if these cells are damaged during enamel formation.

FUSION AND GEMINATION

A double-appearing tooth can represent either fusion or gemination. Diagnosis can be difficult because both conditions result in one large tooth. Fusion and gemination are more commonly seen in the anterior segments, especially incisors and canines.1,2 Proper diagnosis requires the counting of the total number of teeth.

Fusion occurs when two developing tooth germs fuse, resulting in one large tooth. Fusion is more frequently seen in the anterior teeth of the deciduous dentition.2 Radiographically, two separate pulp cavities are visible.2,3 The patient will not have a full set of teeth and it will appear as if one tooth is missing (Figure 1). Gemination occurs when a tooth germ attempts to separate but fails. In the incisal area, there is often a notch marking where the tooth attempted separation.2,3 Gemination is seen in both deciduous and permanent teeth, and is most common in the anterior and maxillary regions (Figure 2).1,4

In the primary dentition, fusion and gemination may create problems with crowding or prevent permanent teeth from erupting. Clinicians should monitor the development and eruption pattern of permanent teeth. In the permanent dentition, esthetic concerns are the main reason patients seek professional care. Treatment modalities include separating the teeth after endodontic therapy or reshaping of teeth.1 Preventive use of sealants should be included in the treatment plan if a deep fissure exists.

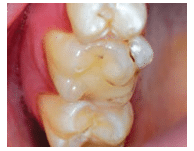

ACCESSORY CUSPS

Accessory cusps represent abnormalities in the development of the cusp region of teeth. Several variations exist, including dens evaginatus, talon cusps, and cusp of Carabelli. Dens evaginatus is an accessory cusp located on the occlusal surface of a posterior tooth (Figure 3). It is usually bilateral, and the permanent premolar teeth are more commonly affected.1 The highest incidence occurs on the mandibular premolars.1,3 The cusp can interfere with occlusion. Dens evaginatus contains pulp tissue in 50% of the cases,1 and pulpal exposure and subsequent periapical pathology can result, secondary to occlusal wear.4–6 Dental hygienists should consistently assess for wear and pulp exposure during periodic exams.

A talon cusp is an accessory cusp on the lingual area of an anterior tooth. The shape of the cusp is similar to an eagle’s talon, hence the name. The majority of cases (75%) occur on the permanent dentition, with 55% of cases occurring on the maxillary laterals and 33% on the centrals.1 The cusp is usually located in the area of the cingulum but can extend toward the incisal edge (Figure 4).4,7 Composed of enamel and dentin, the talon cusp may include a pulp horn. Radiographic examination usually reveals a cusp centered on the crown with distinct enamel and dentin (Figure 5).1 Early diagnosis is particularly important because, similar to dens evaginatus, the talon cusp’s location places it at risk for occlusal wear with possible subsequent pulp exposure. Careful examination during exams is essential.

The cusp of Carabelli is an accessory cusp located on the mesiolingual cusp of maxillary permanent or deciduous molars. These cusps vary in size and may have a groove located between the cusp and the underlying mesiolingual cusp (Figure 6). The cusp location presents no clinical problems unless caries develops in the groove. Sealants should be considered in cusps with deep grooves.

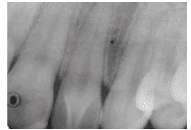

ECTOPIC ENAMEL AND ENAMEL PEARLS

Ectopic enamel refers to the presence of enamel in an abnormal location. Enamel pearls are small spheres of enamel deposited on the root surface during tooth development. They can be found on both deciduous and permanent dentitions. Maxillary permanent molars are the most commonly affected.1,5 Enamel pearls are usually located in the furcation area near the cementoenamel junction. They are often detected on radiographs and appear as small round opacities (Figure 7). The location and shape of enamel pearls are clinically significant, as they interfere with attachment and could increase the risk of periodontal diseases.1,4,5,8 Treatment involves thorough oral hygiene and monitoring of the patient’s periodontal status. In cases of progressive loss of epithelial attachment, removal of the enamel pearl may be indicated.

TEETH NUMBERS

The number of teeth that develop in the mouth can vary. A total absence of tooth development is a rare phenomenon called anodontia. Partial anodontia or hypodontia refers to the lack of one or several teeth. Hyperdontia denotes an increased number of teeth, which are called supernumerary teeth.

The development of teeth is strongly controlled by genetics, with more than 200 genes affecting it.1 Anodontia, hypodontia, and hyperdontia are common manifestations of a variety of syndromes but are also encountered in healthy patients. Most cases of anodontia occur in patients with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia—an inherited condition affecting tissue and structures derived from ectoderm.

Hypodontia is a common finding in the permanent dentition. The teeth most commonly missing include third molars, maxillary lateral incisors, and second premolars.3–5 Hypodontia is caused by both environmental and genetic factors, and is a common manifestation of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and Down syndrome.5,9 In ectodermal dysplasia, the number of teeth is reduced and the teeth appear conical. Patients with Down syndrome often experience hypodontia and may also exhibit malformed teeth and malocclusion secondary to excessive crowding.3 The treatment depends on the severity of the case. In many cases, spacing and tipped teeth are a concern. A multidisciplinary approach that includes an orthodontist is recommended.10

Supernumerary teeth develop from additional tooth germs of the dental lamina in the primary or permanent dentitions. They can also develop when a tooth germ separates into two separate teeth. Supernumerary teeth vary in size and shape, with some appearing normal while others look small and underdeveloped. Most cases of hyperdontia are isolated occurrences but others are familial or associated with a syndrome.5 Single tooth hyperdontia is more common in the permanent dentition and occurs more frequently in the maxilla (90%) than in the mandible (10%).4 Multiple supernumerary teeth occur more often in the mandible (Figure 8).1

Hyperdontia is a common manifestation of syndromes, such as Gardner syndrome and cleidocranial dysplasia. Gardner syndrome is a rare hereditary condition characterized by the presence of colorectal polyps at high risk for malignant transformation. Other findings include tumors of the skin and dental abnormalities, such as odontomas and impacted teeth.1 Cleidocranial dysplasia is a disorder of bone that results in bony defects affecting the skull and clavicle. Patients exhibit large skulls and hypoplastic clavicles. Related dental abnormalities include cleft palate, retention of primary teeth, and a delay or failure of permanent teeth to erupt.1 The presence of numerous supernumerary teeth, which often remain unerupted, is another symptom.

Supernumerary teeth can impinge on surrounding teeth and potentially create problems. Impacted supernumerary teeth can delay or block the eruption of surrounding teeth. Erupted ones often create alignment and crowding problems and serve as local contributing factors for the development of caries and periodontal disease. In cases of progressive attachment loss or an increase in caries due to positioning, extraction of the supernumerary tooth may be required.

SIZE AND STRUCTURE OF TEETH

The terms microdontia and macrodontia refer to teeth that are abnormally smaller or larger than normal teeth. In localized microdontia, one tooth presents smaller than normal and the shape is often conical. The most common occurring microdont is the maxillary lateral incisor or peg lateral (Figure 9), followed by maxillary third molars.1,3–5 Microdont teeth do not require treatment but peg laterals often pose esthetic problems. These teeth are frequently restored with composite bonding or veneers.

Enamel dysplasia is caused by abnormal enamel development due to an insult to ameloblasts during tooth development. Enamel dysplasia can present as hypoplasia or hypocalcification. In hypoplasia, the quantity and shape of the enamel are affected, resulting in a pitted or rough surface.2 In hypocalcification, the quality and color of enamel are marred, resulting in a smooth surface differing in color from white to yellow to brown.2 Many factors can influence the enamel formation process and alter its appearance. The extent of the alteration depends on the intensity of the causative factor, duration of the injury, and the period in crown development during which the injury takes place.4,5

The structure of enamel can be affected by environmental and genetic influences. Environmental effects may be caused by prolonged illness, inflammation, fluoride, or trauma.4 The effect can occur locally (impacting one or two teeth) or systemically (affecting the entire dentition). Enamel abnormalities and defects can also be caused by genetics. Enamel hypoplasia is often a manifestation of systemic disease and syndromes. A thorough medical and dental history is essential in determining the cause of enamel dysplasias.

TURNER’S TOOTH

Traumatic injury or prolonged inflammation in the area of a developing tooth can result in enamel hypoplasia or Turner’s tooth. The affected permanent teeth can appear deformed and demonstrate pits and discolorations (Figure 10). The most common cause is traumatic intrusion or prolonged inflammation secondary to an abscess of a primary tooth into the developing enamel organ of a permanent tooth.5,11 Treatment is usually not required, though severe cases may need restorative treatment for esthetic reasons and/or to address dentinal hypersensitivity. The effects of the injury do not manifest until years after the insult, when the permanent teeth erupt. In order to diagnose Turner’s tooth, clinicians must inquire about trauma and/or local infections during the first years of life.

A systemic illness, particularly one accompanied by fever and skin eruptions (eg, scarlet fever, chicken pox, measles), can affect enamel and cause visible changes to tooth structure.1,3 Nutritional deficiencies in vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin D, calcium, and phosphorus can impact enamel formation.3 This type of enamel hypoplasia occurs only on teeth that were developing during the period of illness. The location of the disturbance correlates with the developmental stage of the teeth affected.1 The hypoplasia can present as rows of pits or areas of missing enamel, with the color varying from white to yellowish brown.

CONGENITAL SYPHILIS

Enamel hypoplasia of permanent incisors and molars can result in patients with congenital syphilis. The incisors taper and develop a notch at the incisal edge, whereas the molars have numerous projections on the occlusal surface. These teeth are respectively referred to as Hutchinson’s incisors and mulberry molars.

DENTAL FLUOROSIS

Fluorosis results from excessive amounts of fluoride (greater than 1 part per million) ingested during tooth development. Fluorosis can result in either hypoplasia or hypocalcification, and the generalized effect can range from mild fluorosis (where white spots to mottled brown discolorations are evident) to severe fluorosis resulting in deeply pitted, irregular or brown enamel (Figure 11).2,3,5 Some cases of severe fluorosis result in weak and soft enamel that fractures and wears.4 Fluorosis usually requires no treatment but its appearance may necessitate restorative therapy.

AMELOGENESIS IMPERFECTA

Enamel hypoplasia is often a manifestation of inherited diseases and syndromes. Amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) is a group of inherited disorders that affects the structure of enamel but is not associated with a systemic disease.1,3 The defect results in enamel that is hypoplastic, hypocalcified, or hypomature. Numerous subtypes with variable patterns of inheritance exist, which account for the wide variation seen in the clinical manifestations.1 In hypoplastic AI, the enamel does not develop to its normal thickness, resulting in enamel defects that can appear pitted, rough, or smooth. The pitted variant is most common and presents as rows or columns affecting mostly the buccal surfaces of teeth.1,2

In hypocalcified AI, sufficient enamel matrix is deposited but fails to mature, resulting in weak tooth structure. There is variation in tooth color, ranging from white to yellowish orange. The enamel is soft and weak, and wears quite rapidly once erupted.

In hypomaturation AI, the enamel matrix is deposited adequately but the enamel fails to properly mature into the normal crystalline structure.1 This type of enamel can appear mottled and shares similar features with hypocalcified AI. A distinctive pattern is evident in one subtype of hypomaturation AI—the snowcapped pattern. In this subtype, the defect manifests as white opaque areas on the incisal and occlusal thirds of teeth. The overlapping features of the different subtypes of AI with severe cases of fluorosis can present a diagnostic challenge. A thorough medical, dental, and family history is required to make the diagnosis.

The severity of the clinical manifestations of enamel hypoplasia dictates the treatment. Esthetic concerns and hypersensitivity are common patient complaints. Small defects can be treated with microabrasion or restorative bonding materials. Severe and complex cases usually require full-coverage restorations, such as veneers or crowns.

CONCLUSION

Tooth abnormalities can present a diagnostic challenge. Dental hygienists need to be able to recognize these abnormalities in order to accurately document them in the patient record. In addition, many of these alterations can impact patients’ oral health, so their risk factors must be noticed and addressed in their treatment plans.

REFERENCES

- Damm DD, Bouquot JE, Neville BW, Allen C, Bouquot J. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:54–94.

- Bath-Balogh M, Fehrenbach MJ. Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:60–64

- Ibsen OA, Phelan JA. Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 6th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2014:162–172.

- Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004:2–17.

- Regezi JA, Sciubba JI, Jordan RC. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 6th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:373–381.

- Uyeno DS, Lugo A. Dens Evaginatus: a review. ASDC J Dent Child. 1996;63:328–332.

- Manujan, Chaudhary S, Nagpal R, Rallan M. Bilateral dens evaginatus (talon cusp) in permanent maxillary lateral incisors: a rare developmental anomaly with great clinical significance. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. Epub ahead of print.

- Romeo U, Palaia G, Botti R, et al. Enamel pearls as a predisposing factor to localized periodontitis. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:69–71.

- Cobourne MT. Familial human hypodontia–is it all in the genes? Br Dent J. 2007;25:203–208.

- Carter NE, Gillgrass TJ, Hobson RS, et al. The interdisciplinary management of hypodontia: orthodontics. Br Dent J. 2003;194:361–366.

- Diab M, elBadrawy HE. Intrusion injuries of primary incisors. Part III: Effects on the permanent successors. Quintessence Int. 2000;31;377–384.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2014;12(7):32-35.