Dental Trauma in Children

Dental hygienists should be prepared to educate parents and patients about the prevention and treatment of traumatic dental injuries.

This course was published in the February 2013 issue and expires February 2016. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- List the risk factors related to traumatic dental injuries.

- Discuss with patients and their families methods to prevent traumatic dental injuries.

- Gather a history of the traumatic injury and perform a brief dental examination.

- Discuss the general treatment considerations for managing dental injuries in children.

Traumatic dental injuries (TDIs) are common occurrences that can present as emergency appointments in dental practices. As many as 25% of school-aged children and 33% of adults experience TDI to their permanent dentition.1 In order to obtain timely and appropriate treatment and follow-up care for TDI, children may miss school and parents or caregivers may need time off from work, which can become a burden, especially for low income and uninsured families. In addition, TDI can be a “scar for life,”2–5 resulting in diminished smiling, laughing, and showing of teeth.6

TDIs occur more often in the maxilla with the central incisors sustaining injury more frequently than lateral incisors. In the primary dentition, a luxation or displacement injury is more common than a fracture, which is the reverse in the permanent dentition.7 TDI occurs most frequently between the ages of 11?2 and 31?2, when toddlers are beginning to walk and explore their environment, and between the ages of 8 and 10, when children experience flared and spaced maxillary incisors8 and engage in more exploratory and high-velocity activities. Patients with special needs, such as those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or poor motor coordination, are at increased risk of TDI.9–12 Boys sustain more TDIs than girls, however, as girls become more involved in physical activities and sports, gender becomes less of a risk factor.1 Children with malocclusions such as Class II dental or skeletal occlusions, increased overjet, proclined incisors, and/or inadequate lip coverage are at increased risk of TDI.13–19

PREVENTION

The risk of TDI can be reduced through proper education of patients, parents, and the community at large. Dental hygienists can obtain educational materials from the Academy of Sports Dentistry,20 American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry,21 and their state dental societies. These materials advise clinicians about how to prevent TDI through the use of protective gear, such as mouthguards; when treatment is necessary; and emergent onsite management that can significantly affect the ultimate prognosis of the teeth involved. In addition, the materials can be used to educate caregivers who are not present at the child’s dental visit. If dental hygienists notice a malocclusion that increases the risk of TDI, they may bring up the option of interceptive orthodontic treatment to reduce this risk.

The American Dental Association (ADA) promotes the use of a well-fitting mouthguard as the best protective device for sports-related TDI.22 There are three major categories of mouthguards.23 A type I (stock) mouthguard is a ready-made, preformed thermoplastic tray that fits loosely over the teeth. It is clenched in place and generally provides poor retention, which interferes with breathing and speaking. Type II (“boil-and-bite” or mouth-formed) is the most commonly-used mouthguard because it is inexpensive and offers better retention than type 1. Made of a thermoplastic material, type II mouthguards are widely available at sporting goods stores. A clinician, parent, or the patient adapts the mouthguard at home by softening the appliance in hot water, briefly cooling it in cool water, placing the appliance over the maxillary dentition with finger, tongue, and some biting pressure in centric occlusion. Since these mouthguards are inexpensive, they are an excellent option for patients with mixed dentition or those in orthodontic treatment. The type III (laboratory-fabricated) mouthguard provides the best protection and is the most widely accepted because it offers the most cushion and best retention. It is generally fabricated with ethyl vinyl acetate (EVA) copolymer and usually requires an outside laboratory for its fabrication and thus is more expensive. There are two varieties of type III mouthguards: IIIa is vacuum-formed and made from one layer while the IIIb is heat-pressure laminated and made of multiple layers with a hard polycarbonate layer in between the EVA layers, which allows for better thickness and wear. The ADA also encourages the use of orofacial protectors, such as helmets and faceguards, to participants in sports that involve direct contact with increased risk of trauma, to not only protect the orofacial structures but prevent concussions as well.

DIAGNOSIS

All dental staff members, including receptionists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants, are part of the front line of TDI management. Dental hygienists can obtain a dental history of the injury, perform a cursory clinical examination, report this information to the dentist, and obtain initial radiographs of the involved area. The dental staff is essential in helping the patient and family immediately feel at ease, which contributes to effective and efficient treatment. This is especially true for young children who are often distraught and frightened.

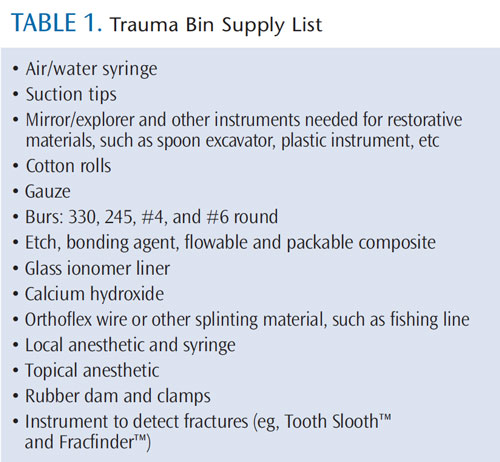

The use of a paper or electronic trauma form allows for the history, clinical and radiographic examinations, treatment, and recommended follow-up care to be systematically recorded. This form can be helpful when records are requested by insurance companies or attorneys involved with litigation (the web version of this article provides a sample form). In addition, the staff can help the dentist create and maintain a “trauma bin,” which contains all of the supplies needed to treat TDI in one place (Table 1). This facilitates the efficient treatment of the traumatized patient, especially during nonoffice hours.

The history of the TDI needs to include the chief complaint, a history of how and when the accident happened, and the child’s past medical and dental histories. In addition, any difficulties with normal occlusion, functional movements of the mandible, or tooth sensitivity should be recorded. This information is then discussed with the dentist who may recommend initial specific radiographic views. Periapical radiographs of permanent incisors are used to assess root fracture, displacement of teeth, proximity of the injury to the pulp, and stage of root development.

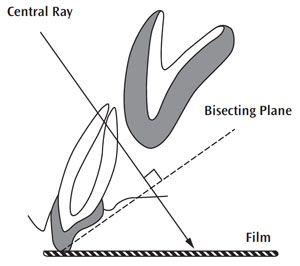

The radiograph will also serve as a baseline from which future radiographs can be compared during follow-up or if post-treatment symptoms or pathology occur. For traumatized primary anterior teeth, an upper occlusal film is the ideal exposure using a #2 film since the child’s palatal vault is not deep enough to accept a periapical film. It is taken using the bisecting angle technique (Figure 1).

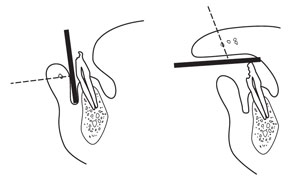

A radiograph of a lacerated lip, cheek, or tongue may be necessary to rule out embedded foreign bodies such as tooth fragments (Figure 2). These films are exposed at one-quarter to one-half of the normal exposure time.

When taking an oral history of the trauma, it is important to note if there are any inconsistencies between the clinical and radiographic findings and the history given. These inconsistencies may be indicative of nonaccidental trauma, ie, abuse, especially when treating young children and those with special needs. Dental hygienists and dentists are mandated reporters in all states and any suspicion of abuse must be well documented in the dental record and reported to the appropriate agency.24–30

MANAGEMENT

Most TDIs are not extremely time-sensitive, however, avulsions of permanent teeth, alveolar fractures, and displacement injuries all require immediate treatment. The International Association of Dental Traumatology periodically publishes guidelines that outline the time sensitivity for all types of TDIs as well as their management.31–35 These guidelines represent the most current evidence-based treatment for any specific TDI. However, each injury should be approached as its own unique situation, and general considerations may override treatment guidelines.

Uncomplicated fractures are coronal injuries to the enamel and dentin that do not involve the pulp. These have historically been referred to as Ellis Class I (enamel only) and Class II (enamel and dentin) fractures, however the complete Ellis classification system is no longer used. A complicated crown fracture (previously referred to as an Ellis Class III fracture) involves the pulpal tissues and is often extremely sensitive to hot, cold, or air stimulation.

In most instances, fractured permanent teeth need to be restored, even temporarily, and if there are pulp exposures, the pulp must be treated with either pulp capping, partial or full pulpotomies, or full pulpal extirpation. Restoration and pulp therapy of fractured primary teeth may not be necessary since no treatment may be the best option based on the child’s level of cooperation, proximity to exfoliation of the involved tooth, and parental wishes. Any tooth with mobility should be assessed radiographically to determine if there are any root fractures.

A tooth can also have a combined crown/root fracture that may involve pulp tissue. Root fractures require stabilization with a resin-wire splint and possible endodontic therapy if pulpal pathology results.

There are several categories of luxation or displacement injuries. A concussion occurs when a tooth sustains trauma, is sensitive to percussion, and is neither mobile nor displaced. No treatment is necessary, but the tooth must be followed since pulpal necrosis is possible. A subluxation occurs when a tooth is mobile, but not displaced in any direction. If the subluxed tooth is very mobile where normal function such as eating or speaking continues to move the tooth, stabilization is necessary to optimize periodontal healing. A lateral luxation occurs when a tooth is moved in either mesially, distally, palatally, or labially from its socket. An intrusion occurs when a tooth is moved from its socket in an apical direction into the alveolar bone. An extrusion is the movement of a tooth in a coronal direction out of the socket, which is sometimes described as a partial avulsion. An avulsion is complete loss of tooth from the socket and supporting gingiva.

Any teeth that are displaced or have sustained a root fracture need to be repositioned and splinted. Permanent teeth that have been avulsed need to be replanted into the socket as soon as possible, ideally within 20 minutes. With primary teeth injuries, the treatment used for permanent teeth can apply, however, factors, such as patient cooperation, expected longevity of the involved tooth, expense, and parent input, are likely to affect the selection of treatment.

SEQUELAE

After TDIs are treated, the teeth are usually monitored over time for any subsequent sequelae, such as pulpal necrosis, periodontal pathology, or discolorations. This monitoring can be performed in conjunction with recare appointments after the initial healing has taken place—usually 3 weeks to 4 weeks. After primary teeth sustain TDI they can change color (Figure 3), cause developmental defects (Figure 4), and/or eruption disturbances to their permanent successors (Figure 5). Color changes in permanent teeth usually indicate a need for endodontic therapy. Dental hygienists spend much of their time counseling patients on their oral health, which should include guidance on all aspects of TDI. Discussions with patients and families regarding TDI should be incorporated into routine recare visits.

REFERENCES

- Glendor U. Etiology and risk factors related to traumatic dental injuries—a review of the literature.Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:19–31.

- Goslee M. The Impact of Dentoalveolar Trauma onOral Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and theirFamilies [doctoral thesis]. Chapel Hill, NC: University ofNorth Carolina School of Dentistry; 2008.

- Lee JY, Divaris K. Hidden consequences of dental trauma: the social and psychological effects. Pediatr Dent. 2009;31:96–101.

- Berger TD, Kenny DJ, Casas MJ, Barrett EJ, LawrenceHP. Effects of severe dentoalveolar trauma on the quality-of-life of children and parents. Dent Traumatol. 2009;24:462–469.

- Rodd HD, Barker C, Baker SR, Marshman Z,Robinson PG. Social judgments made by children inrelation to visible incisor trauma. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26:2–8.

- Cortes MI, Marcenes W, Sheiham A. Impact oftraumatic injuries to the permanent teeth on the oral health-related quality of life in 12-14-year-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:193–198.

- Borssen E, Holm AK. Treatment of traumatic dental injuries in a cohort of 16-year-olds in northernSweden. Endod Dent Traumatol. 2000;16:276–281.

- Andreasen JO, Ravn JJ. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries to primary and permanent teeth in a Danish population sample. Int J Oral Surg.1972;1:235–239.

- Lalloo R. Risk factors for major injuries to the face and teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2003;19:12–14.

- Sabuncuoglu O, Taser H, Berkem M. Relationship between traumatic dental injuries and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: proposal of an explanatory model. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21:249–253.

- Avsar A, Akba? S, Ataibi? T. Traumatic dental injuries in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:484–489.

- Ferreira MC, Guare RO, Prokopowitsch I, SantosMT. Prevalence of dental trauma in individuals with special needs. Dent Traumatol. 2011;27:113–116.

- Forsberg, C. & Tedestam, G. Etiological and predisposing factors related to traumatic injuries to permanent teeth. Swed Dent J. 1993;17:183–190.

- Nguyen QV, Bezemer PD, Habets L, Prahl-Andersen B. A systemic review of the relationship between overjet size and traumatic dental injuries.European Journal of Orthodontics. 2000;21:503–515.

- Brin, I., Ben-Bassat, T., Heling, I., & Brezniak, N.Profile of an orthodontic patient at risk of dental trauma. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21:503–515.

- Bauss O, Röhling J, Schwestka-Polly R. Prevalence if traumatic injuries to the permanent incisors in candidates for orthodontic treatment. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:61–66.

- Shulman JD, Peterson J. The association between incisor trauma and occlusal characteristics in individuals 8-50 years of age. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:67–74.

- Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi-Farahani A,Eslamipour F. An investigation into the association between facial profile and maxillary incisor trauma, a clinical non-radiographic study. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26:311–316.

- Bonini GC, Bönecker M, Braga MM, Mendes FM.Combined effect of anterior malocclusion and inadequate lip coverage on dental trauma in primary teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28:437–440. Dent Today. 2004;23:128–134.

- Academy for Sports Dentistry. FAQs. Available at: www.academyforsportsdentistry.org/Resources/FAQs/tabid/73/Default.aspx. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry ClinicalAffairs Committee, American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Policy on prevention of sports-related orofacial injuries. Pediatr Dent. 2008–2009;30(Suppl):58–60.

- ADA Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations; ADA Council on ScientificAffairs. Using mouthguards to reduce the incidence and severity of sports-related oral injuries. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1712–1720.

- American Society for Testing and Materials.Standard practice for care and use of mouthguards. Designation: F 697–680. Philadelphia: American Society for Testing and Materials. 1986;323.

- Becker DB, Needleman HL, Kotelchuck M. Childabuse and dentistry: Orofacial trauma and its recognition by dentists. J Am Dent Assoc.1978;97:24–28.

- Needleman HL. Orofacial trauma in child abuse:Types, prevalence, management, and the dental profession’s involvement. Pediatr Dent.1986;8(Suppl):71–80

- Jessee SA. Physical manifestations of child abuse to the head, face and mouth: a hospital survey. ASDCJ Dent Child. 1995;62:245–299.

- Naidoo S. A profile of the oro-facial injuries in child physical abuse at a children’s hospital. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24:521–534

- Cairns AM, Mok JY, Welbury RR. Injuries to thehead, face, mouth and neck in physically abused children in a community setting. Int J Paediatr Dent.2005;15:310–318

- Kellogg N, American Academy of PediatricsCommittee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Oral and dental aspects of child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1565–1568.

- United States Department of Health and HumanServices. Child Welfare Information Gateway.Mandatory reporters of child abuse and neglect:Summary of state laws. Available at: www.childwelfare.gov/systemwide/laws_policies/statutes/manda.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2013.

- Diangelis AJ, Andreasen JO, Ebeleseder KA, et al.International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28:2–12.

- Andersson L, Andreasen JO, Day P, et al.International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28:88–96.

- Flores MT, Andersson L, Andreasen JO, et al.Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. I. Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2007;23:66–71.

- Flores MT, Andersson L, Andreasen JO, et al.Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: II. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2007;23:130–136.

- Flores MT, Malmgren B, Andersson L, et al.Guidelines for the management of traumatic dentalinjuries: III. Primary teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2007;23:196–202.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2013; 11(2): 58, 61–63.