SPUKKATO/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

SPUKKATO/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Creating an Ergonomic Workspace

Oral health professionals need to pay close attention to ergonomics to prevent musculoskeletal disorders and ensure quality of life.

Recently, Business Insider published an article ranking the most health-damaging jobs. Of the 37 careers on the list, dental hygienists ranked number one, general dentists ranked number two, dental laboratory technicians ranked number four, and dental assistants ranked number five.1 As such, it is imperative that oral health professionals use standard precautions and work to make their workplaces safe. Oral health professionals are at risk for fatigue and discomfort due to static positions, poorly designed workspaces, and the exertion of repetitive and forceful motions. This can lead to the development of musculoskeletal disorders, decreased career length, and impaired quality of life. Proper ergonomics is key to supporting the musculoskeletal health of clinicians. Ergonomics is defined as maximizing efficiency and safety in the workplace through strategically positioning how people work and designing the function of the work area.2

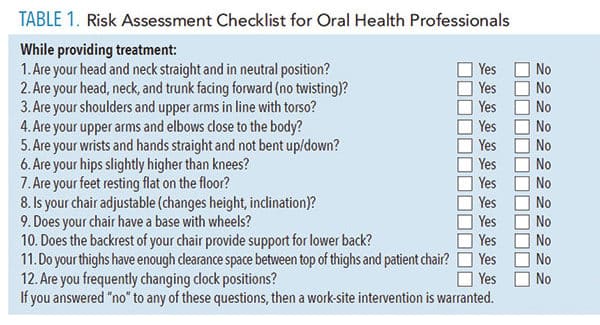

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), identifying the problem is an important step to improving ergonomics in the workplace. This includes a careful, periodic observation of the workplace and an individual’s work practices.3 Table 1 includes a risk assessment checklist modified from OSHA’s Computer Workstation eTool to determine if a work-site intervention is justified and provide a guide for appropriate ergonomics in the dental office.4

![ergonomics]() OBTAINING AND MAINTAINING ERGONOMICS

OBTAINING AND MAINTAINING ERGONOMICS

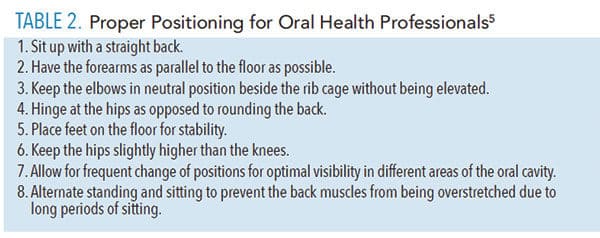

The clinician’s primary goal should be obtaining and maintaining a neutral position throughout the day. At the beginning of each day, clinicians should properly set their chair to what is most comfortable and allow for appropriate positioning. Additionally, posture should be checked during each appointment at specific times to ensure they are maintaining proper positioning. For example, at the start of a new quadrant while scaling, a clinician can check his or her posture and positioning. This is a simple, quick check that can help decrease operator fatigue and increase safety. Table 2 lists the key tenets of proper positioning for oral health professionals.5

During instrumentation, clinicians need to maintain a neutral wrist where the wrist is straight and in line with the forearm. Appropriate fulcrums are vital to assist in control of the instrument and reduce muscle load in the hand.6 Additionally, clinicians should implement a wrist-forearm motion while instrumenting and avoid excessive finger movements.

Loupes may help enhance body posture and reduce strain. However, loupes must be properly fitted by an experienced manufacturer representative. Ill-fitting loupes and improper use can place the clinician at an increased risk of musculoskeletal disorders.7 To increase illumination in the oral cavity, a headlight that attaches to safety glasses or loupes may be helpful. Headlights should be lightweight with a portable battery pack.5

Chair design can support proper positioning and clinicians should carefully consider what chair is best suited for them. Following are some important characteristics of a well-designed chair: stability, adjustable for proper height and incline positioning, base with wheels to allow maneuverability, padded seat with waterfall edge, and convex lumbar support that is adjustable to accommodate varying clinician heights.8

Chair design can support proper positioning and clinicians should carefully consider what chair is best suited for them. Following are some important characteristics of a well-designed chair: stability, adjustable for proper height and incline positioning, base with wheels to allow maneuverability, padded seat with waterfall edge, and convex lumbar support that is adjustable to accommodate varying clinician heights.8

Another important consideration is glove selection. Gloves need to properly fit the clinician’s hands because loose-fitting gloves can decrease control of instruments and tight-fitting gloves can constrict blood circulation.9

Daily schedules should reflect strategic placement of case difficulty by alternating between scaling and root planing patients and recare patients. Scheduling challenging cases back-to-back may lead to an increased rate of operator fatigue.

Workspace design should be simple and easy to navigate. Clinicians should arrange their workspace for maximum efficiency, reduce the number of controls, and place everything in consistent patterns. The light, bracket tray, handpiece, suction, gauze, and anything else needed during an appointment should be easy to access to prevent awkward movements such as twisting and leaning. In order to ensure the clinician can easily work in the 12 o’clock operator position, a clearance of 20 inches to 22 inches is needed between the dental chair headrest when it is in supine position and the counter.5

POSITIONING PATIENTS

Patients should sit all the way back in the dental chair with their heads placed on the headrest properly. Headrests should be easily adjustable in order to accommodate different sizes and needs. Contouring pillows or a chair with a double-articulating headrest can help with proper patient positioning. Additionally, the patient chair should be able to move around, if needed, to provide adequate space between the headrest and counter.10

The arch the clinician is working on should dictate if the patient is in supine or semi-supine positioning. While instrumenting on the maxillary arch, the maxillary occlusal plane should be as perpendicular to the floor as possible. As such, the patient should be reclined to supine. While instrumenting on the mandibular arch, the mandibular occlusal plane should be as parallel to the floor as possible. As such, the patient should be reclined to semi-supine at about 20° above horizontal.5 Some patients may present with medical conditions that prevent them from laying back all the way. After careful attention to the medical history, clinicians should work with the patient to determine how best to provide treatment.

The height of the patient’s chair when it is laid back should be enough so that the patient’s mouth is around the same level of the clinician’s elbows while in a neutral position. Moreover, the patient’s chair height should be adjusted to allow for the clinician to freely turn beneath the patient’s chair and prevent the clinician’s knees from contacting the patient chair.11 Clinicians should also have patients turn their head to the right or left when needed to work on certain areas of the mouth.

CONCLUSION

Working to maximize efficiency and safety in the dental office may reduce the occurrence and severity of musculoskeletal disorders and increase quality of life. Oral health professionals should be conscientious in ergonomics and maintaining neutral body positioning throughout the day.

REFERENCES

- Kiersz A, Gillett R. The 37 jobs that are most damaging to your health. Business Insider. April 27, 2017.

- Merriam-Webster. Definition of Ergonomics. Available at: merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ergonomics. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- United States Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Ergonomics: Identify Problems. Available at: osha.gov/SLTC/ergonomics/identifyprobs.html. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- United States Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Computer Workstations eTool. Available at: osha.gov/SLTC/etools/computerworkstations/checklist_evaluation.html. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Kagan J. Ergonomics. In: Henry R, Goldie MP. Dental Hygiene Applications to Clinical Practice. 2016. Philadelphia: FA Davis Co; 2016:394-407.

- Dong H, Barr A, Loomer P, Rempel D. The effects of finger rest positions on hand muscle load and pinch force in simulated dental hygiene work. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:453–460.

- Ludwig E, Tolle SL. Ensure proper fit. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2017;15(4):24–26.

- Valachi B. Operator stools: how selection and adjustment impact your health. Dentistry Today. Available at: dentistrytoday.com/ergonomics/1109-. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Ayoub HM, Darby ML. Ergonomic best practices. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(4):30–34.

- Valachi B. Ergonomic guidelines for selecting patient chairs and delivery systems. Dentistry Today. Available at: dentistrytoday.com/ergonomics/1112–sp-52800858. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Gupta A, Bhat M, Mohammed T, Bansal N, Gupta G. Ergonomics in dentistry. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2014;7:30–3

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2019;17(8):32–33.

OBTAINING AND MAINTAINING ERGONOMICS

OBTAINING AND MAINTAINING ERGONOMICS