Create the Informed Dental Patient

Consumers who are knowledgeable about oral health and disease are more likely to accept treatment, adhere to therapy guidelines, and experience successful outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Patient education is so enmeshed in our lives as dental hygienists that many times we offer explanations and suggestions on autopilot. Sometimes it’s important to take a step back to re-evaluate our techniques and make sure they are effective in helping us reach patients. In the following article, Jacqueline J. Freudenthal, RDH, MHE, will explore how patients’ learning styles can impact the way they acquire information and how dental hygienists can adapt their techniques to best suit individual patient needs. Most important, you’ll learn about specific strategies you can adopt to ensure your messages get through to patients—as well as how to incorporate these strategies efficiently—because time is always of the essence in the operatory. We hope this article provides just the information you need to tweak, polish, or completely reinvent your patient education techniques.

—Jana Berghoff, RDH, FAADOM

Technology Marketing Manager, Patterson Dental

Effective patient education is the cornerstone of successful treatment outcomes. Dental hygienists are often the primary providers of patient education, as they spend the most time with patients. Clinicians must remain up to date on the latest educational strategies to support successful recare, compliance, and treatment acceptance.

Patient education has long been central to dental hygiene’s philosophy of practice. Alfred C. Fones, DDS, understood the need for education and disease prevention when he trained Irene Newman to be the first dental hygienist in 1906. Regarding the purview of dental hygienists, Fones said: “It is primarily to this important work of public education that the dental hygienist is called. She must regard herself as the channel through which dentistry’s knowledge of mouth hygiene is to be disseminated. The greatest service she can perform is the persistent education of the public in mouth hygiene and the allied branches of general health.”1

There are many tools available to educate today’s dental patients. Individuals now have access to a wealth of health information and an increased desire to be highly informed. Much of the available information is unvetted, so it is essential that oral health professionals first provide effective and engaging patient education in the dental office—and then advise patients on how to find and identify accurate and reliable data and educational materials for at-home use. Informed patients become partners in promoting their personal health, instead of just consumers of services.2

Health care reforms in the United States are forcing a shift away from treatment, and toward health promotion and disease prevention to encourage successful outcomes. Providing effective education and health promotion serves to empower patients as partners in their health care decisions. This, in turn, builds value and provides an opportunity to improve patients’ oral health. Most adults are motivated to learn about topics relating to their health concerns. Open communication, collaboration, and problem solving help identify patients’ goals, concerns, and desires.

PATIENT EDUCATION AIDS

Professional in-office education systems can provide patients with relevant, up-to-date information about services offered by the practice, as well as details about treatments and oral health conditions. Three-dimensional animations are available, and serve as powerful tools in assisting patients to better understand the disease process and treatment options (Figure 1). Some systems include the ability to email patients videos and presentations related to their treatment plans. Quality patient education materials can be found through a multitude of professional organizations and dental companies that realize the importance of knowledgeable patients.

PATIENT-CENTERED APPROACHES

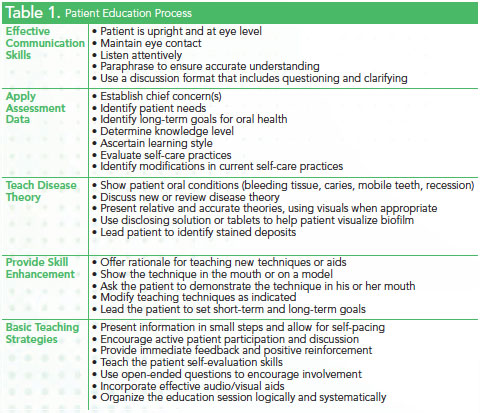

Successful patient education relies on both communication and interpersonal skills (Table 1). Skillful communication enables clinicians to perform routine tasks, such as obtaining a thorough medical history, explaining a diagnosis or prognosis, recommending treatment, and providing instruction and education. Interpersonal communication skills involve eye contact, body orientation, posture, listening, cues, and distance. Clinicians with these skills can reduce anxiety and fear among patients and encourage the formation of trusting relationships.3 In order to ensure their full participation in the oral health decision-making process, patients must have the opportunity to express their values and preferences. This requires patients to be informed and understand treatment decisions. Misunderstandings or ineffective delivery of information can cause patients to delay or avoid treatment. The use of video may improve clinician-patient interaction simply due to the placement of computer screens in the operatory.

The average American adult reads at a seventh-grade to eighth-grade level, and the National Institutes of Health recommends that patient education materials be written at a fourth-grade to sixth-grade reading level. Even if patients are able to read the words, they may not be able to fully understand the meaning and context of the information, which can negatively impact health outcomes.4 Using appealing visual aids and minimal text in patient education materials may improve comprehension among those with low reading levels or when English is a second language. Varied educational approaches can serve the needs of diverse patient populations and age groups.

Motivation plays an important role in determining the outcome of therapy, and clinicians’ enthusiasm influences patient motivation. This does not mean patients who are less motivated cannot realize positive health outcomes. Every patient is an individual and requires the clinician to create an effective means of encouragement. Dental hygienists are ethically obligated to help patients understand the etiology of their oral health problems and explain how to prevent or limit the progression of oral diseases.

Patient education is an art. Each teacher-patient relationship is unique and requires skill and astute judgment to provide successful therapeutic communication—or the interpersonal exchange of information to initiate healthy behavior change(s).5 When changing behaviors, it may be more important to know what patients are NOT willing to do than what they are willing to do. The basic principles of therapeutic communication include: active listening, paraphrasing, and reflective responding.

Active listening is one of the most important aspects of the communication process and requires concentration and focus on what the patient is conveying. Paraphrasing provides an opportunity to clarify and correct misunderstandings. Reflective responding addresses patients’ emotions and reflects what they are feeling. Asking open-ended questions and paying attention to both verbal and nonverbal messages help clinicians better understand patients’ perspectives. Matching learning styles and delivery styles may enhance individualized patient education and lead to more successful outcomes.

LEARNING STYLES

The term “learning styles” is used to describe the way individuals prefer to acquire new information. This includes how information is gathered, processed, interpreted, and organized.6 When people are absorbing new information, they have a natural tendency or preference for a style of learning. Much of the research published on learning styles is focused on the academic setting; however, the VARK (visual, aural, read/write, and kinesthetic sensory modalities) theory is conducive to patient education in health-care settings.7 The theory also addresses multimodal learners who use a combination of sensory modalities during the learning process.

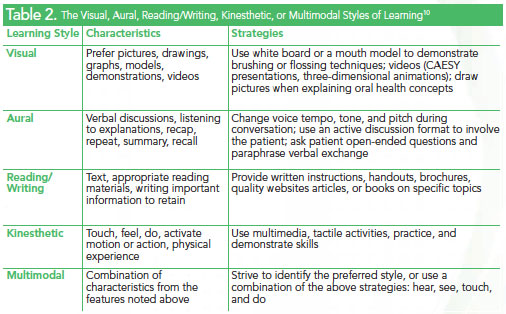

Visual learners process information through models, pictures, illustrations, and or a combination of printed materials with charts and symbols (Figure 2). Aural learners prefer spoken language, where concepts are verbally explained in an atmosphere with few distractions that may interfere with listening. Read/write learners prefer reading, writing, and text. Kinesthetic learners do best with experience and practice of the task or activity. Multimodal learners switch from one style to another based on the material they are trying to absorb.

The most effective teaching strategy involves personalizing the message to fulfill the patient’s needs (Table 2).7,8 Although dental hygienists may not typically ask patients to complete a learning styles questionnaire, many individuals are able to characterize their learning preferences from past experiences. A basic understanding of learning preferences can limit misunderstandings during patient education and the informed consent process. The one-on-one relationship between patient and dental hygienist provides an ideal opportunity for implementing flexible learning approaches.9

Strategies for tailoring oral health education to visual learners may include using a white board to draw pictures, models, videos, and three-dimensional animations. Professional organizations and dental product manufacturers have developed high-quality, cost-effective materials designed to help oral health professionals educate their patients. Many offices provide an opportunity for individual patients to encounter educational materials via technologies in the office. This frequently occurs in reception and treatment areas (Figure 3). It is essential for clinicians to follow up with each patient to answer questions and ensure comprehension of concepts and recommendations. Educational videos may stimulate questions regarding how patients’ conditions compare to those in the video or materials. Changes in voice tone, tempo, and a discussion format help involve the read/write style patients. There is a plethora of quality written instructions, brochures, articles, and websites to assist read/write learners.

Tactile activities that allow the patient to touch, activate, and demonstrate specific skills are helpful to kinesthetic learners. Many individuals are multimodal or use a combination of characteristics without a predominant learning style. A see, hear, touch, and do approach may be helpful for these learners.

Millennials, or those whose birth years range from the early 1980s to the early 2000s, may need a different approach to engage them in the education process. These tech-savvy young people have always been plugged in. They are accustomed to learning in digital formats and receiving customized data, and may respond best to a personalized, digital approach vs a “talking head.”10 Millennials are typically less formal than older generations and may appreciate a more casual approach.10

Regardless of learning style, repetition and consistent messaging enhance the retention of patient education materials. Offices must make a concerted effort to ensure that clinicians are disseminating congruent information to patients about prevention strategies, treatment planning, and oral diseases, and that these messages are repeated at every appointment.10

Focusing teaching strategies to meet individuals’ learning styles can increase motivation, improve retention, and enhance the quality and effectiveness of patient education.

PATIENT EDUCATION AT HOME

In the past decade, the use of the Internet has grown exponentially among all age groups. Most people use this resource to find answers to their health-related questions. Unfortunately, there is no evaluation process to ensure websites contain information that is accurate and appropriate for consumers. Reading health information on the Web without context or evidence to support it can confuse consumers and lead to poor decision making.

Many quality websites exist that clinicians can recommend with confidence. Medline Plus is a nationally recognized consumer website sponsored by the National Library of Medicine that posts current, evidence- based information. The site provides data about diseases, conditions, and wellness in understandable language. A search feature allows users to type in lay terms to find information regarding medications, symptoms, or health problems. It provides a description and links to other quality sites, articles, tutorials, and videos that further explain injuries, diseases, procedures, and treatments.11

Many patient education systems also offer an at-home component. The presentations viewed in the dental office can often be printed for patients to take home, and some systems can email links to patients so that they can review educational videos at home.

Improve Your Patient Education

Capabilities with CAESY Cloud Patient Education Systems

CAESY Patient Education Systems online via CAESY Cloud offer instant access to more than 350 multimedia presentations, accessible by PC and MAC including iPads, iPhones, and smartphones.

CAESY features three-dimensional animation and models, full-motion video, narration, and colorful images for both adult and pediatric audiences. Practices can access patient education resources from multiple locations within the practice.

CAESY video links can be placed directly onto a practice website, or sent to patients’ email to view privately at a later time.

New videos and features are frequently posted and installation and network connections between participating computers are not required. CAESY is available in both English and Spanish, and is backed by Patterson Dental’s renowned support and customer service and the team at the Patterson Technology Center.

Visit caesycloud.com to learn more, or to sign up for CAESY today.

COLLABORATIVE APPROACH

An innovative design for the future practice of health care is centered on a more collaborative and coordinated approach. In 2006, the World Health Organization developed a strategy for health care delivery that incorporates interprofessional teams of health care providers.12 There is a growing body of literature that suggests interprofessional collaboration improves patient and clinician satisfaction, increases access to health care resources, and reduces costs and errors.12 A bidirectional relationship between oral health and physical health is needed. New practice models for dental hygiene are emerging to ensure educational qualifications are sufficient to safely provide the scope of services necessary to participate as an effective collaborative team member. More than half of all states presently allow patients direct access to preventive services provided by dental hygienists.

As part of a health care team, dental hygienists will be called upon not only to educate patients but also health care professionals from other disciplines about the importance of oral health and its impact on systemic health. Dental hygienists will continue to serve as leaders in oral health education and promotion. Using a myriad of proven and future technologies remains the focus of effective patient education today and in the future.

REFERENCES

- Fones AC. Mouth Hygiene. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1934.

- Gordon J. Educating the patient: challenges and opportunities with current technology. Nurs Clin N Am. 2011;46:341–350.

- Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Cole-Kelly K, et al. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79:495–507.

- Hansberry DR, Shah R, Schmitt PJ, et al. Analysis of the readability of patient education materials from surgical subspecialties. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:405–412.

- Darby ML, Walsh MM. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:42.

- Marcy V. Adult learning styles: how the VARK© learning style inventory can be used to improve student learning. Journal of the Association of Physician Assistant Programs. 2001;12(2):1–5.

- Inott T, Kennedy B. Assessing learning styles: practical tips for patient education. Nurs Clin N Am. 2011;46:313–320.

- Russell S. An overview of adult-learning processes. Uro Nurs. 2006;26:349–370.

- Robertson L, Smellie T, Wilson P, Cox L. Learning styles and fieldwork education: students’ perspectives. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011;58(1):36–40.

- Price C. Why don’t my students think I’m groovy?: the new “Rs” for engaging millennial learners. The Teaching Professor. 2009;23(1):7.

- Medline Plus. About Medline Plus. Available at:?nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ aboutmedlineplus.html. Accessed March 10, 2014.

- Pinto A, Lee S, Lombardo A, et al. The impact of structured interprofessional education on health care professional students’ perceptions of collaboration in a clinical setting. Physiother Can. 2012;64:145–156.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2014;12(4):35–38.