Create a Culture of Safety

Dental practices that foster safety in the workplace may see improved treatment outcomes and more satisfied patients and employees.

Safety culture refers to the manner in which safety is managed in the workplace and often reflects “the attitude, beliefs, perceptions, values, and behaviors that employees share in relation to safety.”1 The term safety culture is relatively new to dentistry, although it has been widely used in medicine—particularly hospital settings—since the 2000 publication of the Institute of Medicine study, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.2 This landmark study found that medical errors cause between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths in the United States each year, generating $17 billion to $29 billion in health care costs.2 Additionally, in 2000, Johns Hopkins Children’s Center and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality found that 4,483 deaths of children younger than 19 were caused by unsafe medical care across 27 states.3 These findings highlight the need to more strongly emphasize the importance of safety in health care settings.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) was created in 1970 in response to a high number of workplace injuries and deaths.4 In 1970, an estimated 14,000 workers were killed on the job.5 In 2010, this number fell dramatically to approximately 4,500.5 The emphasis of workplace safety with regulatory enforcement has helped foster a culture of safety in many professional settings.

EXPANDING THE ROLE OF SAFETY CULTURE TO DENTAL SETTINGS

Today, hospitals routinely perform quality assurance audits to ensure safety in the workplace. Dentistry, by comparison, is not fully developed in this area.6 The nature of the dental setting is different from a hospital environment. Dental patients are most often ambulatory, and they typically are not critically ill nor highly susceptible to health care-associated infections. For the most part, dental offices operate as small businesses with less scrutiny from regulatory agencies, which can lead to lax reporting and a false sense of security.7 Dental errors are generally less noticeable than medical errors, as they rarely result in death. Groups studying morbidity, mortality, and the financial impact of health care errors have not noted dental errors as high priorities because of dentistry’s low morbidity and mortality rates.7

With 210,036 licensed dentists practicing in the US, however, dentistry needs to become more entrenched in safety culture.8–10 Every oral health professional should adhere to ethical principles by using safe work behaviors and causing no harm. Being safety conscious helps to avoid costly errors, improves patient satisfaction, and increases profits. Promoting a culture of safety also leads to better legal security.6 Compliance with guidelines and recommendations reduces errors and the risk of litigation.

Unfortunately, a lack of safety culture in the dental setting has led to several high-profile incidents in which patients were harmed. For example, in 2013, an Oklahoma oral surgeon lost his license after a highly publicized breach of several safety protocols.11 The breach was discovered after several patients became infected with hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and the human immunodeficiency virus. Upon investigation, a multitude of safety violations was discovered such as an absence of spore testing, use of rusted and pitted instruments, numerous infection control and sterilization violations, and clinicians working outside of their scopes of practice. For instance, dental assistants were permitted to administer sedation.11 These types of safety violations result from a lack of safety culture.

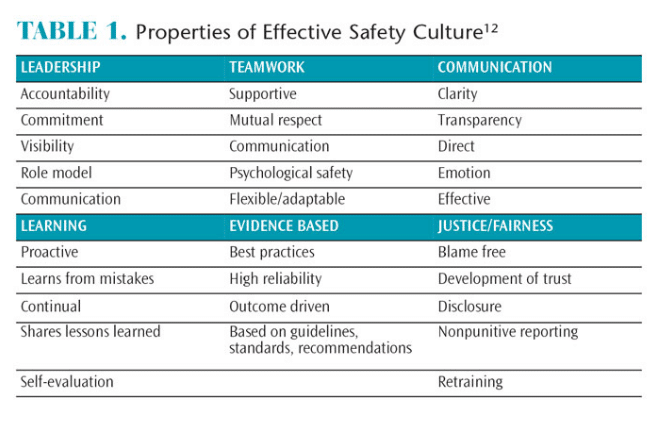

A review of the literature by Sammer et al12 identified seven properties of an effective safety culture: leadership, teamwork, evidence-based decision making, communication, learning, justice/fairness, and patient-centered care (Table 1).12 Safety culture begins with the members of the senior leadership team. Their beliefs and actions set the tone for safety culture.13 The first step in creating a culture of safety is ensuring that senior leadership buys into this concept. Leaders should set safety benchmarks and monitor employee progress, facilitate training, define the roles and responsibilities of employees, develop and monitor systems for accountability, and provide feedback.13 Leaders must be consistent in their messaging.

Teamwork, a sense of cooperation, and respect for one another are key aspects of a positive safety culture. Correcting hazards as soon as possible is important. Team members must learn from their mistakes and seek additional education in infection control.12

Protocols and procedures must be based on sound evidence, and standardization of procedures needs to occur. Communication is another key component of safety culture. Employees must feel free to voice their opinion on behalf of patient safety.12,14 All employees (regardless of their position) must feel safe about providing feedback to others. Praising safe behaviors and recognizing unsafe behaviors promotes workplace safety.12 Safety should be integrated into day-to-day operations as a routine part of the work environment.14

BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTING A SAFETY CULTURE IN THE DENTAL ARENA

Sammer et al12 describe several barriers to creating a safety culture, including poor leadership, lack of teamwork, communication problems, and absence of incentives for continued learning. Leaders who do not model effective safety behaviors or do not enforce safety guidelines cannot expect employees to safely perform. Employees will rise to the standard set forth by the supervisor.

A survey of 765 US dental hygienists investigated participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings, 2003.15 The results showed that high compliance with the infection control guidelines was associated with positive safety beliefs and actions, whereas low compliance was related to less positive safety beliefs and practices.15 When participants believed safety was important, they were more compliant with infection control guidelines. Conversely, when they believed safety was not as important, compliance with the guidelines declined. Some of the barriers listed by survey participants included time to adequately perform safety behaviors, lack of staff education, poor attitudes and cooperation of other staff members, unwillingness of employers to support infection control efforts, and a lack of knowledge. One key finding was that the dentist/practice owner was very influential in establishing the safety culture in the practice.15

STRATEGIES FOR IMPLEMENTING A SAFETY CULTURE IN THE DENTAL PRACTICE

Organization is the first step in assessing the safety culture of an organization.12 Safety culture begins with the leader in the practice. It is a vision that cannot be imposed—it must be shared and embraced by all. Current policies and procedures should be reviewed to determine whether they are in compliance with regulatory mandates, guidelines, and recommendations. Establishing safety instructions and sharing those with the dental team is vitally important. Holding regular staff meetings, attending continuing education courses, and providing annual safety training are additional ways to enhance the safety culture in a practice.

Safety should be a routine part of daily work. Good communication among staff members builds trust and promotes safety. A positive culture of safety results in good treatment outcomes, happy patients, satisfied staff, and reduces the risk of legal action.

References

- Cox S, Cox T. The structure of employee attitudes to safety: a European example. Work and Stress. 1991;5:93–104.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2000.

- Miller MR, Zhang C. Pediatric patient safety in hospitals: a national picture in 2000. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1741–1746.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. About OSHA. Available at: osha.gov/about.html. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Commonly Used Statistics Federal OSHA Coverage. Available at: osha.gov/oshstats/commonstats.html. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Yamalik N, Perea Perez B. Patient safety and dentistry: what do we need to know? Fundamentals of patient safety, the safety culture and implementation of patient safety measures in dental practice. Int Dent J. 2012;62:189–196.

- Leong P, Afrow J, Weber HP, Howell H. Attitudes towards patient safety standards in U.S. dental schools: a pilot study. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:431–437.

- Ramoni R, Walji M, Tavares A, et al. Open wide: looking into the safety culture of dental school clinics. J Dent Educ. 2014;78:745–756.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Dentists by State 1993-2011. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2013/104.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Professionally Active Dentists. Available at: kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-dentists/. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention. OSAP Press Release March 30, 2013. Available at: osap.org/?page=Oklahoma&hhSearchTerms =%22press +and+release%22. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Sammer CE, Lykens K, Singh KP, Mains DA, Lackan NA. What is patient safety culture? A review of the literature. J Nurs Scholarship. 2010:42:156–165.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Creating a Safety Culture. Available at: osha.gov/SLTC/etools/safetyhealth/mod4_factsheets_ culture.html Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Agnew J. Seven keys for creating a safety culture. Available at: aubreydaniels.com/blog/2013/01/23/7-keys-for-creating-a-safety-culture. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Garland KV. A survey of United States dental hygienists’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices with infection control guidelines. J Dent Hyg. 2013;87:140–150.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2016;14(03):24–26.