MONKEYBUSINESSIMAGES / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

MONKEYBUSINESSIMAGES / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

Communicating About Sensitive Topics

While addressing issues like sexually transmitted infections, obesity, and tobacco use is not easy, oral health professionals are obligated to educate patients on key factors related to oral and systemic health.

This course was published in the September 2016 issue and expires September 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the importance of educating patients about sexually transmitted infections, obesity, and tobacco use.

- Identify strategies for addressing sensitive topics with patients.

- List the American Medical Association’s 14 communication skills for improving health counseling and compliance.

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

Oral health professionals may hesitate to discuss the human papillomavirus (HPV) as a potential etiology for head and neck cancers, due to its status as the most common sexually transmitted infection.4 However, the most frequent mode of HPV transmission is through oral sex, putting this topic into the purview of oral health professionals.5

The number of lifetime sexual partners is an important risk factor for HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.6 Oral HPV infection has been associated with approximately 72% of all oropharyngeal cancers.7 HPV prevalence in oropharyngeal cancers increased from 16.3% between 1984 and 1989 to 71.7% from 2000 to 2004, reflecting a 225% rise within 20 years.8

The increase in HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers emphasizes the need for provider/patient communication concerning risk factors and vaccine availability. Vaccines that target the cancer-causing strains of the virus—primarily HPV-16 and HPV-18—are available for both girls and boys.9 The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends HPV vaccination for children at age 11 or 12, or prior to their first sexual activity.4 Educating adolescents and their parents about the risk factors for HPV and head and neck cancers can help prevent viral transmission. Since 2006, when the vaccinations were first recommended, HPV transmission among teen girls in the US has decreased by 56%.4

Oral HPV testing is available in the dental setting and can serve as an adjunct to current head and neck cancer screening procedures. Oral health professionals should be prepared to make appropriate referrals based on assessments and information obtained through the patient interview.

The CDC estimates that an average of 50,000 new cases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are diagnosed annually. Men who sleep with men account for 68% of these new cases, and African American and Hispanic/Latino populations are disproportionately affected.10 In 2012, 1.2 million people were infected with HIV, and 12.8% of those infected were unaware of their status.11 Informing patients of the risk factors associated with HIV, as well as routes of transmission (blood, semen, preseminal fluid, and breast milk that directly contact mucosal membranes or pass into the blood stream) could help prevent future transmissions.12

Educating patients about safe sex, limiting sexual partners, avoiding needle sharing, and the importance of testing will help them make informed decisions and may help prevent the spread of HIV infection. Providing dental patients with on-site HIV rapid salivary testing can assist in early diagnosis and treatment, and may establish an opportunity for more in-depth discussions about sexual practices and their relationship to health. Table 1 provides strategies for discussing sexual health.13

OBESITY PREVENTION

OBESITY PREVENTION

With so much societal emphasis on weight and appearance, discussing obesity in the dental setting can be daunting. It is a complex disease that is not easily managed by behavioral intervention. Obesity prevention and treatment require a multidisciplinary approach and interprofessional collaboration among oral health professionals, nutritionists, physicians, exercise specialists, and psychologists. Obesity is directly related to low self-esteem14 and feelings of shame,15 which may increase provider apprehension when initiating communication. An unhealthy diet often leads to dental caries; however, clinicians tend to avoid discussing its effect on general health and well-being.

Obesity affects approximately 78.6 million adults and 17% of children in the US, increasing the risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, certain cancers, gallbladder disease and gallstones, osteoarthritis, gout, and breathing problems, including obstructive sleep apnea and asthma.16 In the past 30 years, childhood obesity has become an epidemic—among children between 12 and 19, its prevalence has more than tripled.17 Many times, overweight and obesity status go unnoticed because children’s parents/caregivers are unaware of the risks posed by being overweight and/or obese. They may not understand the definition of clinical obesity and its related risk for developing serious, long-lasting health problems.18

Obesity can lead to health concerns that last well beyond childhood. For example, obesity can cause sleep apnea due to excess soft fatty tissue in the windpipe that blocks airways during the rest state.19 An apneic episode occurs when the windpipes become occluded during sleep, which can increase stress hormones and contributes to both diabetes and obesity.19 Research has also linked obesity to increased risk for periodontal diseases. A recent literature review concluded that obesity is a state of hyperinflammation, decreasing the body’s immune response to Porphyromonas gingivalis, thus increasing the likelihood of a periodontal condition.20

One of the most significant health implications of obesity is type 2 diabetes, which results in insulin resistance, with eventual beta cell failure over time. Approximately 86 million people in the US are prediabetic.21 Without diet modifications and improved physical activity, 15% to 30% of these individuals will become diabetic within 5 years and insulin dependent for the rest of their lives.21 Many dental patients may be diabetic or prediabetic but unaware of their status.21 The dental setting may be an ideal environment for performing random blood glucose screening for diabetes and prediabetes, with referral to a primary care provider for further testing and diagnosis.22

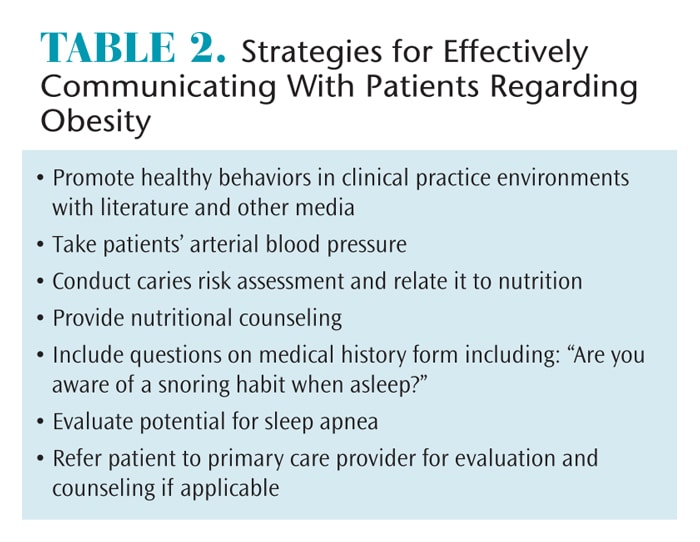

Effective communication regarding obesity should include adequate time for patient questioning regarding overall health, including diet and activity recommendations.18 Nutritional counseling coupled with improvements in physical activity may help the patient adopt a healthier lifestyle. Table 2 lists strategies for communicating with patients regarding obesity.

TOBACCO CESSATION

Even though smoking has decreased by 50% over the past 50 years, 45 million people in the US still smoke. More than 16 million Americans experience smoking-related diseases, such as asthma, emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, cancer, diabetes, low-birth weight babies, immune system dysfunction, and an increased risk for tuberculosis.23 One third of all cancer deaths in the US are linked to smoking, including 87% of all lung cancer deaths, 32% of all coronary heart disease deaths, and 78% of all COPD-related deaths.1

Tobacco is the number one risk factor associated with oral cancer. When tobacco use is combined with heavy alcohol use, the risk for head and neck cancer increases.24 Tobacco use diminishes oral esthetics and compromises periodontal health. The results of both surgical and nonsurgical therapy are negatively impacted when an individual uses tobacco due to chronic inflammation and a compromised immune response.25

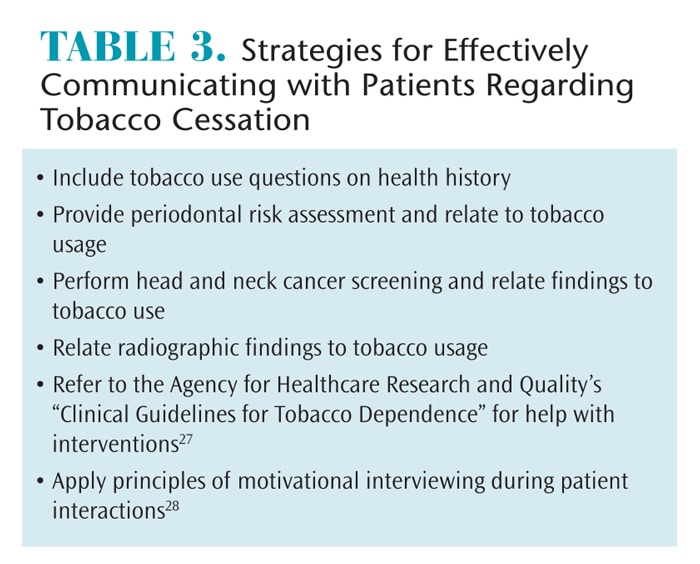

Tobacco use is a personal choice, and ineffective interventions can lead to denial and hostility. In 2012, dental hygiene students participated in a randomized controlled trial to assess if tobacco dependence counseling improved their comfort levels when addressing patients. The study concluded that while the counseling did initially improve their comfort levels, clinical experience appeared to be of greater significance.26 Acquiring the educational tools necessary to present current and valid information coupled with consistent application can provide oral health professionals with the confidence to address tobacco cessation and other difficult issues. Table 3 includes tips for discussing tobacco cessation with patients.27,28

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

Oral heath professionals are typically not educated on effective communication. A 2010 study surveying medical students from the US and Canada found that students’ comfort levels with addressing sexual issues were directly associated with their perceived level of training.1 A study by Merrill et al2 suggests that practicing physicians and senior medical students often have difficulty inquiring about sexual health with their patients, noting embarrassment, low self-esteem, shyness, anxiety, and inadequate training as the main impediments.

The perception that patients are unwilling to discuss sexual health is a legitimate concern, although it may be unfounded. A recent Australian study revealed that patients were willing to talk about sexually transmitted infections when their general practitioner underscored the importance of the dialogue.29

While addressing sensitive topics may be uncomfortable, time constraints present another obstacle to quality health counseling. A cross-sectional analysis revealed that more than half of respondents perceived their interactions with health care providers as too brief and that their feelings were not adequately addressed.30

Compliance and behavioral adjustments are contingent upon the patient’s ability to comprehend the information provided. Oral health professionals need the tools to appropriately address patients on their level of understanding.

Health literacy experts and the American Medical Association (AMA) developed 14 communication techniques for health care providers to enhance health counseling and compliance.31

- Using simple language (avoiding technical jargon)

- Asking if patients would like family members to be in the discussion

- Asking patients to repeat information (teach-back technique)

- Speaking more slowly

- Drawing pictures

- Following up with telephone call to check understanding/compliance

- Using models to explain

- Writing down instructions

- Reading instructions aloud

- Underlining key points in patient information handout

- Asking patients to follow up with office staff to review instructions

- Questioning patients on how they will follow instructions at home

- Presenting two or three concepts at a time and check for understanding

- Handing out printed material to patients

Techniques, such as the teach-back method and use of plain language, assist with patient comprehension and compliance, thus improving health outcomes.32 In addition to using laymen terms and placing information in common contexts, research suggests that decreasing the number of choices provides for better informed patients.33

Resources are available to help clinicians obtain the skills necessary to communicate regarding these topics. The Sexual and Reproductive Health Workforce Project has created an initiative to integrate sexual and reproductive health into core curricula for health programs and has designed continuing education modules for interprofessional teams.34 These initiatives are being implemented not only in the US but worldwide. In 2015, the World Health Organization released a public health booklet addressing sexual communication.35 The goal was to integrate brief sexuality-related communication (BSC) into common practice for health care professionals with a focus on sexual health.35 BSC addresses sexual health informally to provide an open line of communication between the patient and the provider.35

The Institute for Healthcare Communication offers courses nationwide to train medical professionals how to “engage, empathize, educate, and enlist” their patients.36 Reputable professional organizations and journals frequently offer quality continuing education courses related to effective patient/provider communications.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals are ethically obligated to address personal and sensitive topics when they affect patient health. The literature supports patient education to prevent the spread of disease. Many patients who perceive themselves as healthy regularly visit their oral health professional two or more times annually and may not routinely visit their primary care provider. These dental care visits provide opportunities for education, screening, and referral. Ensuring that clinicians are equipped with the tools necessary to tackle sensitive topics and comfortably initiate communication with patients is critical.

References

- Shindel AW, Ando KA, Nelson CJ, Breyer BN, Lue TF, Smith JF. Medical student sexuality: how sexual experience and sexuality training impact U.S. and Canadian medical studentss’ comfort in dealing with patientss’ sexuality in clinical practice. Acad Med. 2010;85:1321–1330.

- Merrill JM, Laux LF, Thornby JI. Why doctors have difficulty with sex histories. South Med J. 1990;83:613–617.

- Champenois K, Cousien A, Cuzin L, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in newly-HIV-diagnosed patients, a cross sectional study. BMC Infec Dis. 2013;13:1–10.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccine Questions and Answers. Available at: cdc.gov/hpv/parents/questions-answers.html. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Dalla Torre D, Burtscher D, Sölder E, Widschwendter A, Rasse M, Puelacher W. The impact of sexual behavior on oral HPV infections in young unvaccinated adults. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20:1551–1557.

- Marur S, D’Souza G, Westra WH, Forastiere AA. HPV-associated head and neck cancer: A virus-related cancer epidemic.Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:781–789.

- Centers for Disease Control and prevention. Number of HPV-attributable cancer cases each year. Available at: cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the united states. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–4301.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements. April 2016. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States: At a Glance. Available at: cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Basic Statistics. Available at: cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Transmission. Available at: cdc.gov/hiv/basics/ transmission.html. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Sexual and Reproductive Health Counselling by Health Care Professionals—Policy Statement. 2011. Available at: sogc.org/ guidelines/sexual-and-reproductive-health-counselling-by-health-care-professionals-policy-statement-replaces-139-dec-2003. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Wang F, Veugelers PJ. Self-esteem and cognitive development in the era of the childhood obesity epidemic. Obes Rev.2008;9:615–623.

- Westermann S, Rief W, Euteneuer F, Kohlmann S. Social exclusion and shame in obesity. Eat Behav. 2015;17:74–76.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Facts. Available at: cdc.gov/obesity/ data/adult.html. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Why Is Obesity a Health Problem? Available at: nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/obe/risks. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Mikhailovich K, Morrison P. Discussing childhood overweight and obesity with parents: A health communication dilemma. J Child Health Care. 2007;11:311,322.

- National Institute of Health. What Causes Sleep Apnea? Available at: nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sleepapnea/causes. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Amar S, Leeman S. Periodontal innate immune mechanisms relevant to obesity. Molec Oral Microbiol. 2013;28:331–341.21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 National Diabetes Statistics Report. Available from: cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014statisticsreport.html. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 National Diabetes Statistics Report. Available from: cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014statisticsreport.html. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Rosedale M, Strauss S. Diabetes screening at the periodontal visit: Patient and provider experiences with two screening approaches. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10:250,258.

- Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Available at: surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/fact-sheet.html. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- National Institutes of Health. Oral Cancer: Causes, Symptoms, and the Oral Cancer Exam. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/oralhealth/Topics/ OralCancer/AfricanAmericanMen/CausesSymptoms.htm. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Bracke KR. Series: New insights into the immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2011;378:1015–1026.

- Brame JL, Martin R, Tavoc T, Stein M, Curran AE. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of standardized patient scenarios on dental hygiene students” confidence in providing tobacco dependence counseling. J Dent Hyg. 2012;86:282–291.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Available at: ahrq.gov/professionals/ cliniciansproviders/guidelinesrecommendations/tobacco/index.html. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press: 2012.

- Baker JR, Arnold-Reed D, Brett T, Hince DA, O’Ferrall I, Bulsara MK. Perceptions of barriers to discussing and testing for sexually transmitted infections in a convenience sample of general practice patients. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19:98–101.

- Spooner KK, Salemi JL, Salihu HM, Zoorob RJ. Patient perspectives and characteristics: disparities in perceived patient–provider communication quality in the United States: trends and correlates. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:844–854.

- Schwartzberg JG, Cowett A, VanGeest J, Wolf MS. Communication techniques for patients with low health literacy: a survey of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(1 Suppl):S96–S104.

- Nouri SS, Rudd RE. Health literacy in the “oral exchange:” an important element of patient–provider communication.Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:565–571.

- Kurtzman ET, Greene J. Effective presentation of health care performance information for consumer decision making: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:36–43.

- Nothnagle M, Cappiello J, Taylor D. Sexual and reproductive health workforce project: Overview and recommendations from the SRH workforce summit, January 2013. Contraception. 2013;88:204–209.

- World Health Organization. Brief Sexuality-Related Communication. Available at: who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/sexuality-related-communication/en. Accessed August 23, 2016.

- Nanchoff-Glatt M. Clinician-patient communication to enhance health outcomes. J Dent Hyg. 2009;83:179.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2016;14(09):58–61.