CE Sponsored by Colgate in Partnership with the American Academy of Periodontology: Maintaining Oral Health in Patients With Special Needs

Periodontal health is intricately tied to oral and systemic health in patients with special needs.

This course was published in the February 2018 issue and expires February 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the barriers to oral health care faced by patients with special needs.

- Discuss the risk of periodontal diseases among special-needs populations, especially those with Down syndrome and cerebral palsy.

- List strategies for providing periodontal treatment to patients with special needs and maintaining their oral health.

- Detail techniques tailored for treating children with special needs.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with disabilities face many challenges in accessing oral health care services. This article reviews the barriers, strategies, and techniques tailored for treating this patient population that focus on promoting periodontal health. For caregivers of individuals with special needs, easy-to-use interactive tools like MagnusCards™, a mobile app that provides step-by-step guidance in oral care activities could help in forming the daily routines that can often be difficult for people living with cognitive special needs. For more information, visit colgate.magnuscards.com.

I hope this article serves as a valuable resource to help you best serve your patients with special needs. The Colgate-Palmolive Company is delighted to have provided an unrestricted educational grant to support “Periodontal Health in Patients with Special Needs” in collaboration with the American Academy of Periodontology.

—Matilde Hernandez, DDS, MS, MBA Scientific Affairs Manager Colgate Oral Pharmaceuticals

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PERIODONTOLOGY

While all patients deserve and require quality periodontal treatment, there are patients whose mental, physical, and developmental limitations necessitate an additional layer of clinical guidance and relational support. Individuals who comprise these special-needs populations face a greater risk of periodontal diseases due to such factors as reduced immune responsiveness, the inability to perform daily oral hygiene tasks, and decreased access to dental care. In this article, educator and American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) member periodontist Lorenzo Mordini, DDS, CAGS, MS, explores the various considerations in the treatment of special-needs patients and in management strategies for oral health professionals providing care.

The AAP is proud to work with Dimensions of Dental Hygiene and Colgate-Palmolive to help ensure the health and wellness of patients from all backgrounds.

—Steven R. Daniel, DDS President, American Academy of Periodontology

Periodontal health is essential to overall health. Patients with poor periodontal health are at increased risk for a variety of ailments, making the treatment of periodontaldiseases of the utmost importance. For patients who struggle with access to care, maintaining periodontal health may be challenging. Patients with special needs often face this dilemma in accessing professional oral health care services and maintaining periodontal health.

The term “special needs” is widely encompassing and includes patients of varying ages and health statuses. The American Dental Association describes patients with special needs as those “who due to physical, medical, developmental or cognitive conditions require special consideration when receiving dental treatment.”1 Special-needs populations may encompass individuals with autism, Alzheimer’s disease, Down syndrome, spinal cord injuries, dementia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychiatric issues, poor mobility, intellectual disabilities, and any other condition that makes the provision of oral health care challenging.1–8 These disabilities may be congenital, developmental, or acquired through disease, trauma, or environmental causes. Patients with special needs may experience difficulty in performing self-care activities and activities of daily living.

According to the United States Census Bureau, approximately 56.7 million individuals or 19% of the American population reported having a disability in 2010, with more than half of those declaring their disability as severe.9 In the past, many individuals with disabilities lived in institutions; this is no longer the case. Today, most people with special needs live in communities and will need to access dental treatment in the private practice setting. Oral health professionals are charged with being prepared to safely and effectively treat patients with special needs.

Unfortunately, patients with special needs often face obstacles to accessing professional oral health care services. Financial issues are the most common barriers among this population, as many individuals with special needs are low income and may rely on government-funded programs, such as Medicaid, for health-care coverage. Language barriers, sensory impairments, psychosocial issues, inaccessible dental offices, and cultural obstacles all impact the ability of patients with disabilities to access oral health care.10–13

RISK FOR PERIODONTAL DISEASES

From medications to environmental exposure to genetics to tobacco use, there are myriad risk factors for periodontal diseases, and special-needs populations are at increased risk. The 2000 Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General noted that patients with special health-care needs have a greater incidence of periodontal diseases compared with the general US population.14Patients with learning and developmental disabilities experience poorer oral hygiene and increased prevalence of and greater severity of periodontal diseases when compared with the general population.15

In addition to the oral health effects of patients with special needs’ specific conditions, the use of medications used in their treatment may also increase the risk for periodontal diseases.15 Some conditions result in an increased risk of periodontal diseases due to individuals’ inability to physically perform routine dental hygiene care. Chronic stress and depression also reduce immune responsiveness.4,16,17 A reduced immune response may increase the host’s susceptibility to periodontal pathogens and lead to periodontal destruction. Poor oral health can affect oral function, leading to malnutrition and compromising the immune system’s ability to protect against disease or infection.18

When treating patients with special needs, oral health professionals need to consistently update medical history forms, including current and past medication use; determine the need for medical consultation with other health care providers; coordinate care with other health care providers; and modify traditional delivery of dental care to accommodate individual patient needs. Clinicians must remember that some systemic diseases are linked to periodontal diseases, while others can lead to poorer periodontal health due to lack of compliance (intellectual disabilities) and physical capabilities (cerebral injuries).

DOWN SYNDROME AND CEREBRAL PALSY

Some patients with special needs have disabilities/disorders that increase the likelihood of developing periodontal diseases and tissue destruction, such as Down syndrome and cerebral palsy. Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality and occurs in approximately one in 700 infants in the US.19 The most common manifestations of Down syndrome include a typical physical appearance and the presence of other medical disorders, such as intellectual disability, congenital heart disease, thyroid dysfunction, high risk of Alzheimer’s disease, and abnormalities of the immune system.20 Individuals with Down syndrome are also at increased risk for destructive forms of periodontal diseases.21,22 Many of these patients are affected early in life with severe gingival inflammation, bleeding on probing, deep probing depths, clinical attachment loss, and crestal bone loss. Khocht at al23 found that those with Down syndrome presented with higher concentrations of a specific bacterial species related to attachment loss compared with patients without the syndrome.

Today, individuals with Down syndrome have an average life expectancy of about 60, a significant increase from 1983 when average life expectancy was 25.24 Oral health professionals have begun addressing the challenges of preventing and treating the high incidence of early onset aggressive periodontal disease in this patient population.25 Some patients with Down syndrome are able to follow dental hygiene instructions and specific oral self-care regimens. Others face more severe developmental challenges and require the assistance of a caregiver for self-care assistance. Periodontal maintenance may also be challenging due to specific common dental anomalies, including underdeveloped midface (prognathism), delayed eruption, open bite, macroglossia, fissured lips/tongue, angular chelitis, missing/malformed teeth, and crowding or spacing.26

Cerebral palsy is caused by injury or altered brain development in utero and presents as difficulty in movement, muscle tone, and/or posture.13 While there is not much research on the life expectancy of individuals with cerebral palsy, most live between 30 years and 70 years, with the longest life expectancy correlating with the lowest severity of the disorder.27 In a study of 100 children with cerebral palsy and 100 healthy controls, Guare Rde and Ciampioni28 found that the children with cerebral palsy had a greater prevalence of periodontal diseases than controls. Individuals with cerebral palsy are at risk of a variety of oral health problems, which can contribute to periodontal disease risk, including: enamel erosion, heavy calculus, malocclusion, bruxism, and increased gag reflex. Providing care for this population can be difficult due to uncontrolled body movements and reflexes.13

PROVIDING PERIODONTAL TREATMENT TO PATIENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

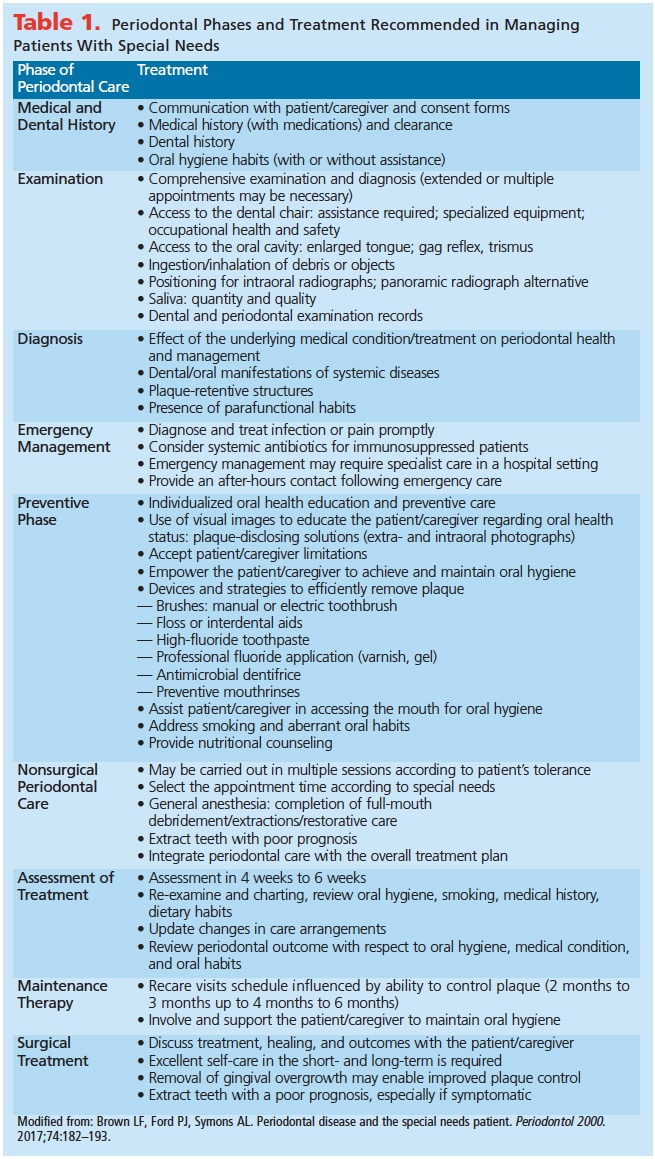

Patients with special needs require examination, treatment, and follow-up care, similar to patients without special needs (Table 1).29Prevention is key to supporting patients with special needs in maintaining overall and oral health. Studies show that regular preventive dental treatment helps to prevent dental caries and periodontal diseases in patients with learning disabilities.30,31Frequent and individualized dental visits can improve patients’ cooperation, resulting in less need for invasive treatment. Packer et al32 found that the need for extractions and extensive treatment, as well as the prevalence of oral diseases, was reduced in individuals with Parkinson’s disease who received individualized preventive dental care.

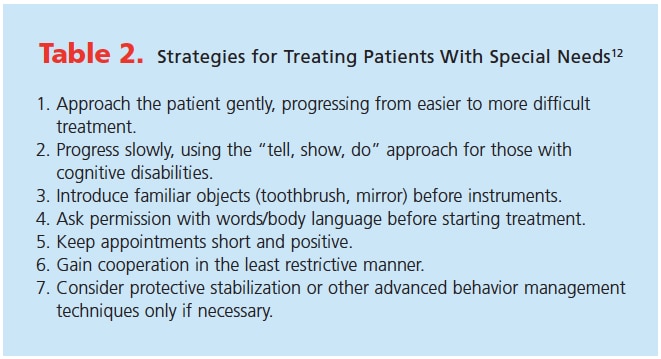

Patience and empathy are required when treating patients with special needs. Missed appointments may be due to issues such as depression and anxiety, limited transportation means, dependence on caregivers, and low socioeconomic status. Building a trusting relationship may help overcome some of the barriers patients with special needs face when accessing oral health care.15Appointments should be scheduled in the morning when patients are most refreshed and they should be kept short. Table 2 lists some additional strategies.12

Patience and empathy are required when treating patients with special needs. Missed appointments may be due to issues such as depression and anxiety, limited transportation means, dependence on caregivers, and low socioeconomic status. Building a trusting relationship may help overcome some of the barriers patients with special needs face when accessing oral health care.15Appointments should be scheduled in the morning when patients are most refreshed and they should be kept short. Table 2 lists some additional strategies.12

In order to avoid the need for major dental reconstructive procedures in this patient population, oral hygiene is paramount. While dental caries is separate from periodontal diseases, many patients experience both oral diseases in tandem, with the shared risk factor being the presence of plaque biofilm. As such, successful biofilm control both at home and in the dental operatory is crucial. Patients should be provided with a written oral hygiene and preventive program, as the stress of dental appointments may decrease understanding of verbal instructions. Maintaining acceptable oral hygiene may be difficult due to a lack of interest and/or understanding, cariogenic diet, physical and intellectual limitations, greater focus on systemic health, and dependence on caregivers.4,7,33–35

Tobacco use may also be an issue among special-needs populations.36 In the US, the prevalence of cigarette smoking among individuals who reported having a disability was 25.4% compared with 17.3% of those who did not report the presence of a disability.37 Those who use tobacco products should be treated the same as traditional patient populations and encouraged to quit and provided with cessation resources.38,39

Daily oral care should be based on mechanical oral biofilm removal and control using a toothbrush and floss or interdental brush (although not appropriate for all special-needs populations, as interdental brushes may lacerate interdental gingiva in sensitive patients).40 As each patient responds differently to oral hygiene methods, other options, such as oral irrigation, may be beneficial. In addition, the use of antimicrobial toothpaste may provide benefits.41 Mouthrinses may also be helpful when patient cooperation is limited but they are contraindicated for patients with oral motor control problems, such as some with cerebral palsy.2,42 Self-care can be challenging due to anatomic limitations, including macroglossia, fissured lips/tongue, angular chelitis, crowding, limited opening,26hyperplasia, and xerostomia.3,34,43,44 In order to facilitate oral hygiene, different oral hygiene aids can be used and modified according to individual patient needs. Power toothbrushes can help a patient with limited hand skills, although they may be too heavy for some patients with hand disabilities. The development of a successful oral hygiene self-care program requires extensive involvement and input from patients and caregivers.

CARING FOR CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

The role of parents/caregivers is important in the treatment of children with special needs. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) defines special-needs care as “any physical, developmental, mental, sensory, behavioral, cognitive, or emotional impairment or limiting condition that requires medical management, health care interve ntion, and/or use of specialized services or programs.”10 Often obtaining cooperation from a young patient with special needs is difficult, so oral hygiene and successful dental appointments will depend on parents/caregivers.

ntion, and/or use of specialized services or programs.”10 Often obtaining cooperation from a young patient with special needs is difficult, so oral hygiene and successful dental appointments will depend on parents/caregivers.

It is important to apply simple modifications and accommodations to make children feel more comfortable, such as short waiting times, scheduling appointments during less busy times, minimizing loud noises and fluorescent lighting, and using the “tell, show, do” approach.

A process of desensitization (reducing anxiety by gradually getting used to the object or situation which causes fear) should begin the dental appointment. The goal is to reduce anxiety to gain cooperation; it can give the patient some control, especially for fearful ones. The most important outcome of initial meetings with patients, caregivers, and clinicians is to implement an individualized preventive oral health program that considers the ability of the patient.45 For more difficult patients, advanced techniques may need to be employed to guarantee the safety of both patients and clinicians. They may include nitrous oxide sedation, protective stabilization, oral/intravenous sedation, and general anesthesia.

Establishing a dental home and the use of anticipatory guidance are important in promoting oral health among all children. Anticipatory guidance is the process of providing practical, developmentally appropriate information about children’s health to prepare parents for the significant physical, emotional, and psychological milestones.45 Individualized discussion should be an integral part of each visit. Topics to be included are oral hygiene and dietary habits, injury prevention, nonnutritive habits, substance abuse, intraoral/perioral piercing, and speech/language development.46,47 Patients with special needs who have a dental home are more likely to receive appropriate dental care.

CONCLUSION

As more individuals with special needs seek medical and dental care in community settings, oral health professionals must be able to provide effective periodontal treatment as well as promote oral health. As patients with special needs are often a neglected patient population, providing individualized care that considers patient limitations is integral to ensuring both oral and systemic health.

REFERENCES

- American Dental Association. Special Needs. Available at: mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/s/special-needs. Accessed January 6, 2018.

- Friedlander AH, West LJ. Dental management of the patient with major depression. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:573–578.

- Little JW. Dental implications of mood disorders. Gen Dent. 2004;52:442–450

- Torales J, Barrios I, González I. Oral and dental health issues in people with mental disorders. Medwave. 2017;17:e7045.

- Cumella S, Ransford N, Lyons J, Burnham H. Needs for oral care among people with intellectual disability not in contact with community dental services. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2000;44:45–52.

- Gopalakrishnapillai AC, Iyer RR, Kalantharakath T. Prevalence of periodontal disease among inpatients in a psychiatric hospital in India. Spec Care Dentist. 2012;32:196–204.

- Morgan JP, Minihan PM, Stark PC, et al. The oral health status of 4,732 adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:838–846.

- Warren JJ, Chalmers JM, Levy SM, Blanco VL, Ettinger RL. Oral health of persons with and without dementia attending a geriatric clinic. Spec Care Dentist. 1997;17:47–53.

- United States Census Bureau. Nearly 1 in 5 People Have a Disability in the US. Available at: census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/miscellaneous/cb12-134.html. Accessed January 6, 2018.

- American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on management of dental patients with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2012;37:166–171.

- World Health Organization. Summary World Repot on Disability. Available at: who.int/disabilities/world_ report/2011/en/. Accessed January 6, 2018.

- Moore T. Caring for patients with special needs. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2016;14(3):58–61.

- Waldman HB, Borg PA, Perlman SP. Periodontal care for patients with special needs.Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2011; 9(9):78–83.

- Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2000;28:685-695.

- Brown LF, Ford PJ, Symons AL. Periodontal disease and the special needs patient. Periodontol 2000. 2017;74:182–193.

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:601–630.

- Warren KR, Postolache TT, Groer ME, Pinjari O, Kelly DL, Reynolds MA. Role of chronic stress and depression in periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2014;64:127–138.

- Chen X, Hodges JS, Shuman SK, Gatewood LC, Xu J. Predicting tooth loss for older adults with special needs. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:235–243.

- Sherman SL, Allen EG, Bean LH, Freeman SB. Epidemiology of Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:221–227.

- Patterson D. Genetic mechanisms involved in the phenotype of Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:199–206.

- Reuland-Bosma W, van Dijk J. Periodontal disease in Down’s syndrome: a review. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:64–73.

- Agholme MB, Dahllof G, Modeer T. Changes of periodontal status in patients with Down syndrome during a 7-year period. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:82–88.

- Khocht A, Yaskell T, Janal M, et al. Subgingival microbiota in adult Down syndrome periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2012;47:500–507.

- Coppus AM. People with intellectual disability: what do we know about adulthood and life expectancy? Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2013;18:6–16.

- Frydman A, Nowzari H. Down syndrome-associated periodontitis: a critical review of the literature. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2012;33:356–361.

- Cheng RH, Leung WK, Corbet EF, King NM. Oral health status of adults with Down syndrome in Hong Kong. Spec Care Dentist. 2007;27:134–138.

- Brooks JC, Strauss DJ, Shavelle RM, Tran LM, Rosenbloom L, Wu YW. Recent trends in cerebral palsy survival. Part II: individual survival prognosis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:1065–1071.

- Guare Rde O, Ciampioni AL. Prevalence of periodontal disease in the primary dentition of children with cerebral palsy. J Dent Child (Chic). 2004;71:27–32.

- Proceedings of the World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics. Chicago: American Academy of Periodontology; 1989:I23–I24.

- Gabre P, Gahnberg L. Dental health status of mentally retarded adults with various living arrangements. Spec Care Dentist. 1994;14:203–207.

- Gabre P, Gahnberg L. Inter-relationship among degree of mental retardation, living arrangements, and dental health in adults with mental retardation. Spec Care Dentist. 1997;17:7–12.

- Packer M, Nikitin V, Coward T, Davis DM, Fiske J. The potential benefits of dental implants on the oral health quality of life of people with Parkinson’s disease. Gerodontology. 2009;26:11–18.

- Dougall A, Fiske J. Access to special care dentistry, part 9. Special care dentistry services for older people. Br Dent J. 2008;205:421–434.

- Waldman HB, Perlman SP. Ensuring oral health for older individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:909–913.

- Desai M, Messer LB, Calache H. A study of the dental treatment needs of children with disabilities in Melbourne, Australia. Aust Dent J. 2001;46:41–50.

- Tonetti MS. Cigarette smoking and periodontal diseases: etiology and management of disease. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:88–101.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in Cigarette Smoking Among Adults With Disabilities. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/documents/cigarettesmokinganddisabilityfactsheet.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2018.

- Stockings E, Bowman J, McElwaine K, et al. Readiness to quit smoking and quit attempts among Australian mental health inpatients. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:942–949.

- Arnsten JH, Reid K, Bierer M, Rigotti N. Smoking behavior and interest in quitting among homeless smokers. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1155–1161.

- Graziani F, Karapetsa D, Alonso B, Herrera D. Nonsurgical and surgical treatment of periodontitis: how many options for one disease? Periodontol 2000. 2017;75:152–188.

- Riley P, Lamont T. Triclosan/copolymer containing toothpastes for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD010514.

- Lacerda DC, Ferraz-Pereira KN, Bezerra de Morais AT, et al. Oro-facial functions in experimental models of cerebral palsy: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2017;44:251–260.

- Peeters FP, deVries MW, Vissink A. Risks for oral health with the use of antidepressants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20:150–154.

- Feldberg I, Merrick J. Dental Aspects. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. 2011:513.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents: clinical practice guidelines. Pediatr Dent. 201638:133–141.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on adolescent oral health care. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:137.

- Lewis CW, Grossman DC, Domoto PK, Deyo RA. The role of the pediatrician in the oral health of children: A national survey. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E84.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2018;16(2):37-42.