AJA KOSKA / E+ / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

AJA KOSKA / E+ / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Caries Prevention Strategies For Older Adults

Oral health professionals play an important role in helping this population maintain their oral health.

Americans continue to live longer and more active lives. In the future, this improved quality and quantity of life is projected to surpass current statistics. By 2060, the number of Americans age 65 and over will increase to 98 million from 46 million currently.1–3 As such, oral health professionals are in a unique position to empower and motivate dental patients to remain free from oral disease well into old age. As health status changes over time, patients can work with oral health professionals to prevent caries and periodontal diseases, helping them to maintain a healthy dentition. Preventive care is critical to this population because of the many complexities that may arise during treatment.

Caries Incidence in Aging Adults

Evidence of coronal caries experience in the older adult population is minimal, however, the literature demonstrates an increased risk for root caries among older adults.4 The Healthy People 2030 initiative, developed by the US Department of Health and Human Services, identifies oral health objectives, and one is to reduce the amount of untreated root decay.5 Approximately 29.1% of older adults have untreated root caries. Overall, more than 90% of American older adults have experienced dental caries.6 The National Institutes of Health reports that 93% of adults age 65 and older have experienced dental caries and 18% have untreated decay.7

Financial, cultural, and structural barriers to care exist for older adults.8 Untreated decay is more prevalent among those experiencing poverty. Approximately one-third of older adults living in poverty have untreated decay, while only 7% of non-poor older adults have untreated decay.9 Older, retired adults may have lost dental insurance coverage upon retirement, and, thus, go without care.10 This population may have other financial burdens brought on by medical conditions. For example, older adults living with Alzheimer disease may need around-the-clock care at home with little to no resources to support dental care.11 Older adults with financial resources experience better oral health outcomes, including maintaining a natural dentition for a longer period of time.

Cultural barriers to care exist, including those related to language, perception, and socioeconomic status. Untreated caries is more than double among Mexican-Americans and Black, non-Hispanic Americans compared to non-Hispanic white Americans.9 These oral health inequalities continue to grow as the topic of whether oral health is an essential component of Americans’ healthcare benefits is hotly debated.9

Structural barriers also exist for older adults. Older adults living in more remote, rural locations may have difficulty accessing care due to a lack of providers or a lack of transportation.12 For older adults living in nursing homes or assisted living communities, this barrier has been amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic.13 These facilities have had to isolate their residents to protect their health. Due to this increased isolation, many older adults have postponed dental care.

Assessing Patient Oral Self-Care Ability and Oral Hygiene

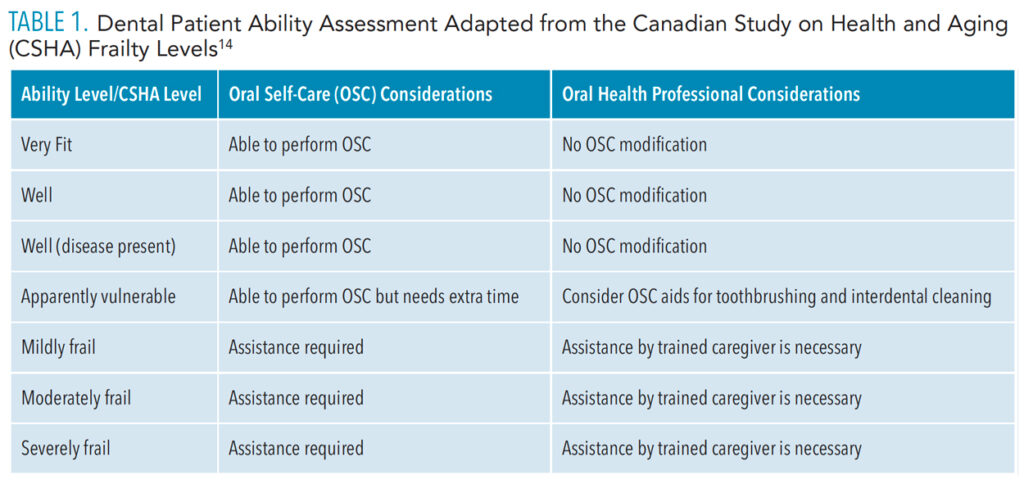

When determining what oral self-care strategies are best suited for older adults, oral health professionals must consider the patient’s ability and dependence on others.8 Individuals living in nursing homes or assisted living facilities may be dependent on caregivers for oral self-care.12 Caregivers need to be educated on oral self-care delivery that is tailored to the individual’s needs. By using a clinical assessment tool, such as the Canadian Study on Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale, the oral health professional can recommend appropriate oral self-care aids based on not only the clinical assessment, but also evaluation of the patient’s ability to perform the tasks (Table 1).8,14

The oral health professional can make informed decisions regarding oral self-care recommendations and treatment after clinical assessment of the patient. In addition to assessing the patient’s ability to properly clean the teeth and mouth, the oral health professional should consider other factors. Older adults may be taking medications that reduce salivary function.15 Older adults who experience common medical conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, may experience dry mouth due to the use of prescription medications.15 The decrease of the protective saliva in the oral environment also increases the patient’s risk for dental caries.

Older adults experiencing dry mouth may benefit from salivary substitutes and the salivary stimulation gained by chewing sugar-free gum containing xylitol.16 Over-the-counter saliva substitutes, lozenges, and oral melts are also available that contain xylitol.17 For older adults with xerostomia, a sialogogue—prescription medication that is used to reinstitute salivary flow—may be indicated.16

Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer disease, and Parkinson disease may impact joints, therefore limiting mobility and making OSC difficult.15 For patients who are unable to independently use oral self-care tools, electric devices, such as power toothbrushes and power flossers, should be considered.

Older adults may also experience depression, which can lead to a lack of motivation or energy to perform oral self-care practices.15 These patients may also consume a poor diet.6,15 Poor oral health may lead to impairment of mastication and therefore contribute to poor nutrition.10 Recommendations should be made for foods with cariostatic properties.6 Oral health professionals should incorporate nutrition counseling into oral self-care instruction for older adults. Beginning with a comprehensive nutritional assessment that includes a thorough review of personal, medical, and dental histories, the oral health professional can motivate the patient to incorporate behavioral changes that support nutritional health.18,19

For all older adults (especially those presenting with poor oral hygiene), additional appointment time may be needed to review proper brushing, flossing, and rinsing techniques. Patients should have a tailored set of recommendations that are based on the assessment of their needs and abilities.

Prevention Strategies

A tell-show-do approach to teaching oral self-care techniques is effective with older adults.11 Any professional recommendation related to oral self-care technique should be demonstrated for the patient. The patient should then perform the technique so that the professional can ensure correct technique that can be replicated at home. While many of the oral self-care recommendations made for this population mirror those recommendations for the rest of the population, each patient’s individual needs and abilities should be assessed.

Many older adults are at increased risk for caries. Due to this, professional fluoride treatments and at-home fluoride mouthrinses should be recommended for those at increased risk.20 Some mouthrinses are formulated to be gentle on the sensitive mouths of older patients. All older adults should use fluoride toothpaste.

For patients with weakened tooth structure or untreated caries, silver diamine fluoride (SDF) may be an option.15 In 2018, the American Dental Association (ADA) stated that SDF could be used as a nonrestorative treatment. Then, in 2020, the ADA supported the use of SDF to arrest caries.15 SDF has been found to arrest root caries in older adults when applied at 6-month intervals.21

Toothbrushing technique should also be selected with the patient’s dexterity in mind. If patients are unable to communicate effectively, they will likely require caregiver support and assistance. This assistance may involve special toothbrushes with modified handles.22 As adults age, hand grip strength decreases and dexterity can be affected.23–25 Toothbrushes with tennis balls or bicycle handles attached to the handle can assist patients with dexterity or hand grip strength issues.

Toothbrushing techniques can be tailored based on patient ability.26 The Bass and modified Bass methods are popular, but the required angulation of the brush (pointed toward the gingiva at 45° to the tooth) may be difficult for older adults with limited dexterity.19 Stillman and modified Stillman toothbrushing methods allow for massage of the tissue and removal of soft debris along the gingival margin. This technique should be considered for patients with recession.18 For older adults with fixed prosthetics and partial dentures, Charters toothbrushing technique, which involves placing the brush at a 45° angle to the occlusal plane while making overlapping, vibratory strokes, should be recommended.19

A study that tracked older adults over 5 years found that those who flossed had less caries incidence.27 Oral health professionals should consider the following factors when determining interproximal cleaning recommendations: dental anatomy, integrity of the gingiva, and interproximal bone levels.19 Interdental brushes are available in different shapes and sizes to accommodate variances in anatomy and embrasure spaces. Interdental brushes are exceptionally effective in biofilm removal on concave tooth surfaces.19 In such areas, dental floss or tape may not be able to cleanse properly, as they are less likely to adapt to the tooth anatomy.

Oral health professionals should select the appropriate sized interdental brush by assessing the embrasure space. A slightly larger brush than embrasure space should be chosen to allow for effective interdental cleansing.18 For older adults with bridgework, floss threaders or tufted floss should be used to cleanse under pontics and interproximal areas of abutment teeth. For patients with limited dexterity and those without caregivers to perform oral self-care for them, power flossers may be recommended. Water flossers may be effective for interdental cleaning in older adults with limited dexterity.19

While the assessment of the oral cavity and consideration of the patient’s ability should inform oral self-care instruction, dental professionals should also consider the patient’s environment. Whether a patient lives alone can be important when making recommendations for vulnerable older adults. Caregivers should be involved in oral health education.

Conclusion

Age impacts oral disease prevalence indirectly through impairment of cognitive and physical capability and directly on a cellular level.8 Limitations due to ability and barriers to care must be recognized when developing oral self-care recommendations. Oral health professionals should advocate for individualized oral self-care plans, including recommendations for brushing and interdental cleaning.8 As the older adult population continues to increase, so does the need for oral health professionals to deliver tailored oral self-care recommendations to their patients.

References

- American Psychological Association. Older Adults and Age-Related Changes. Available at: apa.o/g/pi/aging/resources/guides/older. Accessed June 18, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Older Persons’ Health. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm. Accessed June 18, 2022.

- World Health Organization. Aging. Available at: who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=t_b_䁯. Accessed June 18, 2022.

- Hendre AD, Taylor GW, Chavez EM, Hyde S. A systematic review of silver diamine fluoride: effectiveness and application in older adults. Gerontology. 2017;34:411–419.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030. Available at: health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/oral-conditions/reduce-proportion-older-adults-untreated-root-surface-decay-oh-04. Accessed June 18, 2022.

- Blostein FA, Jansen EC, Jones AD, Marshall TA, Foxman B. Dietary patterns associated with dental caries in adults in the United States. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2020;48:119–129.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Dental Caries in Adults. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/dental-caries/seniors. Accessed June 18, 2022.

- Tonetti MS, Bottenberg P, Conrads G, et al. Dental caries and periodontal diseases in the ageing population: call to action to protect and enhance oral health and well‐being as an essential component of healthy ageing–Consensus report of group 4 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseasesJ J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:S135–S144.

- Yarbrough C, Vujicic, M. Oral health trends for older Americans. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150:714–716.

- Allin S, Farmer J, Quinonez, C, et al. Do health systems cover the mouth? Comparing dental coverage for older adults in eight jurisdictions. Health Policy. 2020;124:998–1007.

- Gao S, Chu C, Young F. Oral health and care for elderly people with Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5713.

- Madunic D, Gavic L, Kovacic I, Vidovic N, Vladislavic J, Tadin A. Dentists’ opinions in providing oral healthcare to elderly people: a questionnaire-based online cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3257.

- Aquilanti L, Santarelli A, Mascitti M, Procaccini M, Rappelli G. Dental care access and the elderly: what is the role of teledentistry? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9053.

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–495.

- Chan AKY, Tamrakar M, Jiang CM, Lo ECM, Leung KCM, Chu CH. Common medical and dental problems of older adults: a narrative review. Geriatrics. 2021;6:76.

- Taverna M. Xerostomia diagnosis and management. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2020:18(4):22–26.

- Salinas T. Dry mouth treatment: tips for controlling dry mouth. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/dry-mouth/expert-answers/dry-mouth/faq-20058424. Accessed June 18, 2022.

- Bowen DM, Pieran JA. In: Darby and Walsh Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 5th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2020.

- Boyd LD, Mallonee LF, Wyche CJ, Halaris, JF. Wilkins’ Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 13th ed. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett; 2021.

- American Dental Association. Clinical Recommendations for Use of Professionally Applied or Prescription Strength, Home-Use Topical Fluoride Agents for Caries Prevention in Patients at Elevated Risk of Developing Caries. Available at: ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/ada_evidence-based_topical_fluoride_chairside_guide.pdf?rev=28cbb81b6c994cc79e127b62e606d0e9&hash=13BA63A12312AE4E6B0754330FF8CF9B. Accessed June 18, 2022.

- Mitchell C, Gross A, Milgrom P, Mancl L, Prince D. Silver diamine fluoride treatment of active root caries lesions in older adults: a case series. J Dent. 2021;105:103561.

- Phadraig CMG, Farag M, McCallion P, Waldron C, McCarron M. The complexity of tooth brushing among older adults with intellectual disabilities: Findings from a nationally representative survey. Disabil Health J. 2020;13:100935.

- Shin NR, Yi YJ, Choi JS. Hand motor functions on the presence of red fluorescent dental biofilm in older community-dwelling Koreans. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2019;28:120–124.

- Saintrain MVL, Saintrain SV, Sampaio EGM, et al. Older adults’ dependence in activities of daily living: Implications for oral health. Public Health Nurs. 2018;35:473–481.

- Dayanidhi S, Valero-Cuevas FJ. Dexterous manipulation is poorer at older ages and is dissociated from decline of hand strength. J Gerontol. 2014;69:1139–1145.

- Rajwani AR, Quaraophia S, Hawes ND, et al. Effectiveness of manual toothbrushing techniques on plaque and gingivitis: A systematic review. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2020;20:843–854.

- Marchesan JT, Bryd KM, Moss K, et al. Flossing is associated with improved oral health in older adults. J Dent Res. 2020;99:1047–1053.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2022; 20(7)14-16,18.