Best Practices for Personal Protective Equipment

The effective use of these infection control tools makes all the difference in ensuring clinician and patient health and safety.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is a crucial component of preventing disease transmission in the dental setting. When appropriate PPE is selected and used as intended, it prevents patient body fluids and operative debris from contacting a clinician’s skin and mucous membranes. This is especially important in dentistry, where potentially infectious droplets and aerosols that may contain blood and saliva are generated during the use of ultrasonic scalers, air/water syringes, and dental handpieces. Additionally, selecting the appropriate PPE for handling potentially contaminated instruments, equipment, and operatory surfaces is critical. In at least two instances over the past several years, bloodborne disease transmission has been linked to dental procedures.1,2

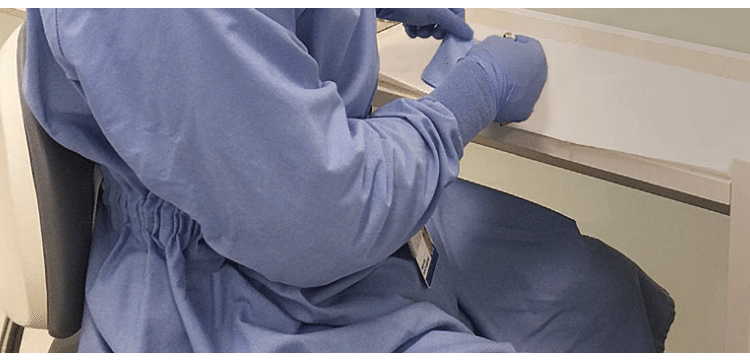

One of the first steps when selecting PPE is to consider the requirements of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. OSHA requires that employers provide and ensure the use of appropriate PPE by employees with occupational exposure to blood and other potentially infectious materials (OPIM), including saliva. OSHA considers PPE appropriate “only if it does not permit blood or other potentially infectious materials to pass through to or reach the employee’s work clothes, street clothes, undergarments, skin, eyes, mouth, or other mucous membranes under normal conditions of use and for the duration of time which the protective equipment will be used.”3 For most dental hygiene procedures, this will include a long-sleeved gown or lab coat, eye protection or face shield, surgical mask, and exam gloves (Figure 1).

GLOVES

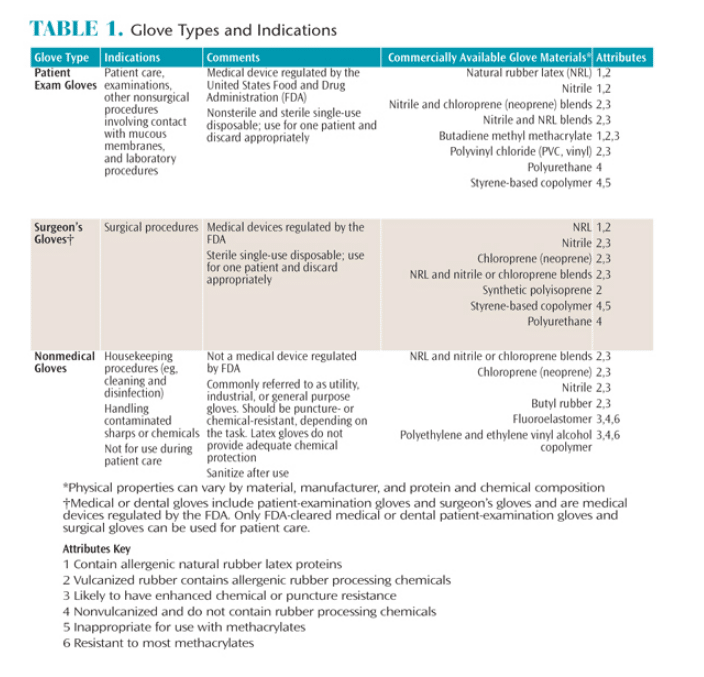

Several types of gloves are recognized as acceptable PPE in the dental office. These include nonsterile exam gloves, sterile surgeon’s gloves, and heavy duty utility gloves. Gloves vary in their puncture-resistance, ability to resist chemical penetration, and potential to cause allergic reactions based on the materials used in the manufacturing process. Table 1 describes the various types of gloves and their specific characteristics.

Nonsterile exam gloves are appropriate for nonsurgical dental procedures, including dental hygiene procedures.4 While the optimal interval for glove changing during long procedures has not been established, there is evidence that undetected microperforations frequently develop in medical gloves somewhere between 30 minutes and 3 hours of use.5,6 Clinicians may also inadvertently contaminate their hands when removing gloves. For these two reasons, hand hygiene should always be performed both before donning and after removing gloves, as well as prior to placing gloves.4 Either alcohol-based hand sanitizer or soap and water may be used for nonsurgical procedures. When using hand sanitizer, apply the amount of product recommended by the manufacturer to the palm of one hand and rub hands together to cover all surfaces of the hands and fingers. Continue rubbing until hands are dry. When using soap and water, wet hands and then apply the amount of soap recommended by the manufacturer to hands, and rub hands together vigorously for at least 15 seconds, covering all surfaces of the hands and fingers. Rinse hands with water and dry thoroughly with a disposable towel. Use the disposable towel to turn off the faucet.7

Sterile surgeon’s gloves are recommended for surgical procedures.4 Exam gloves and sterile surgeon’s gloves are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but sterile surgeon’s gloves have a lower threshold for defects than do nonsterile exam gloves.8 Sterile surgeon’s gloves have not been shown to be significantly more effective in preventing infection during nonsurgical procedures, and, consequently, there are no recommendations for the routine use of sterile surgeon’s gloves for nonsurgical procedures.

Unlike medical exam and sterile surgeon’s gloves, heavy duty utility gloves are not regulated by the FDA because they are not used for medical procedures.4 Utility gloves should be worn when handling sharp contaminated instruments, during the cleaning and packaging of instruments in preparation for sterilization, and during all cleaning and disinfection procedures implemented in a contaminated operatory.

MASKS

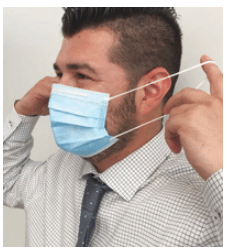

Surgical face masks play a critical role in protecting clinician mucosal tissues from contact with oral fluids, operative debris, and aerosols during patient care. Medical face masks are divided into performance classes based on their fluid resistance, bacterial filtration efficiency, and submicron particle filtration efficiency. They are also rated for flame spread.9 Medical face masks are designated either as level I, level 2, or level 3, with level 1 providing the lowest barrier performance and level 3 offering the highest. Manufacturers label the mask with the level designation and must validate their claims with the FDA.10 Clinicians should consider the nature of the planned procedure when selecting face masks. Procedures with little or no potential for spatter could be performed using a level 1 mask. When a higher likelihood of spatter is anticipated—like when a prophy angle or ultrasonic instrument is used—the clinician may want to consider a level 2 or level 3 mask.

Masks may become moist from contact with spray from dental devices and from the wearer’s exhaled breath. This moisture affects the mask’s ability to effectively filter small particles. If a mask becomes damp it should be changed between patients or during patient treatment, if possible.4

PROTECTIVE EYEWEAR

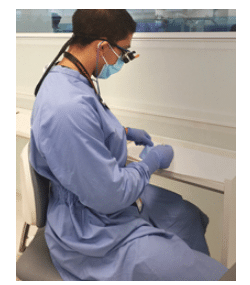

Protective eyewear should be worn whenever contaminated aerosols, splatter, blood, or OPIM may be generated while performing dental procedures.3,4 OSHA identifies goggles or glasses with solid side shields, or chin-length face shields, as appropriate eye protection. Loupes should be fitted with side shields to protect the wearer’s eyes from spatter that could enter from the sides (Figure 2). The eye protection must be sufficient to prevent blood, saliva, and other materials that are generated during dental procedures to reach the mucous membranes of the eyes.

OSHA requires that eye protection comply with one of three American National Standards Institute (ANSI) consensus standards if the work involves hazards from flying objects, molten metal, liquid chemicals, acids or caustic liquids, chemical gases or vapors, or potentially injurious light radiation.11 The OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard does not specify that eye protection comply with ANSI standards. Procedures should be evaluated, and if it is determined that impact-resistant eye protection is needed due to the risk of projectiles, a comprehensive eye and face protection program should be established as required by the OSHA Eye and Face Protection Standard.12

GOWNS AND LAB COATS

OSHA requires that all skin, street clothes, and work clothes be protected against contact with patients’ fluids and OPIM.3 For most hygiene procedures, this requirement can be met by wearing either a long-sleeved gown or long-sleeved lab coat over street clothes, uniform, or scrubs. Scrubs alone are not sufficient protection when the potential for splatter or spray containing blood or OPIM exists.13

Protective clothing should be changed daily, or more often if it becomes soiled with blood or OPIM.3,4 Both the CDC and OSHA agree that a single gown or lab coat may be worn for multiple patients as long as there is no visible contamination. It’s important to remember that guidelines and regulations are considered minimum standards and clinicians may always elect to exceed those guidelines and regulations if they feel it prudent or necessary. The scientific literature reflects that the overall risk of disease transmission from contaminated textiles is very low.14

Contaminated disposable gowns should be placed in a designated receptacle that is labeled with the universal biohazard symbol. Reusable contaminated gowns or lab coats should be placed in a designated container labeled with the biohazard symbol3 for laundering. According to OSHA standards, employees may not take soiled laundry home to be cleaned but are permitted to launder items at the office if standard precautions are observed, including the use of PPE when handling contaminated laundry.15 Alternately, a professional service that launders items used in medical and dental facilities may be used, but they too must follow standard precautions in the handling of the contaminated laundry. When selecting a laundering vendor, the vendor should be asked to confirm it trains its employees in standard precautions.

DONNING AND REMOVING PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidance on the correct sequence for placement and removal of PPE in health care settings.16 The first item to don is the gown or lab coat. The second item is a face mask. The mask should be worn with the ties or elastic bands at the middle of the head and the neck. The flexible band (if present) should be fitted to the bridge of the wearer’s nose, and the mask should fit snugly to the face with its lower edge positioned below the chin. The mask is followed by placement of goggles or a face shield. Finally, after appropriate hand washing, gloves are donned. Gloves should extend over the cuff or edge of the gown or lab coat to completely cover the clinician’s skin.

After patient treatment, all exterior surfaces of PPE should be considered contaminated and handled with care to prevent contact with the clinician’s skin or clothing. Gloves should be carefully peeled off and turned inside out as they are removed, grasping the outside only with gloved fingers (Figure 3). To remove goggles or face shields, grasp the back of the earpieces or headband, remove carefully, and place in a receptacle until they can be cleaned and decontaminated. Disposable eye protection should be discarded immediately upon removal. To remove masks without contaminating the wearer’s hands and face, the clinician should grasp the mask by the bottom ties or elastics, grab the top, and remove without touching the front of the mask (Figure 4).16 Remove gowns or lab coats by turning them inside out and placing them in a designated bin for laundering or disposal.

CONCLUSION

Clinicians must be well versed in the appropriate procedures when selecting and donning PPE if they are to be successful in reducing the risk of exposure to infectious agents and accidents. Dental practices need to have an effective protocol in place to ensure the safety and well-being of both clinicians and patients.

References

- Redd JT, Baumbach J, Kohn W, Nainan O, Khristova M, Williams 24 I. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis B virus associated with oral surgery. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1311–1314.

- Radcliffe R, Bixler D, Cleveland J, et al. Infection control: hepatitis B virus transmissions associated with a portable dental clinic, West Virginia, 2009. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1110–1118.

- US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 29 CFR Part 1910.1030. Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens; needlesticks and other sharps injuries; final rule. As amended from and includes 29 CFR Part 1910.1030. Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens; final rule. Federal Register. 1991;56:64174–64182.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–61.

- Hubner NO, Goerdt AM, Mannerow A, et al. The durability of examination gloves used on intensive care units. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:226

- Partecke LI, Goerdt AM, Langner I, et al. Incidence of microperformation for surgical gloves depends on duration of wear. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:409–414.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51:No RR–16.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff Medical Glove Guidance Manual. Available at fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/ DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM428191.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- ASTM Standard F2100. Standard Specification for Performance of Materials Used in Medical Face Masks. Available at: astm.org/Standards/F2100.htm. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- FDA. Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Surgical Masks—Premarket Notification [510(k)] Submissions; Guidance for Industry and FDA. Available at: fda.gov/ MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm072549.htm. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 29 CFR Part 1910.133. Eye and Face Protection. Available at:?osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/ owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=9778. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Eye and Face Protection e-tool. Available at: osha.gov/SLTC/etools/eyeandface/faqs.html# protection. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Enforcement Procedures for the Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens. Available at: osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=directives&p_id= 2570. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- Sehulster LM, Chinn RYW, Arduino MJ, et al. Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities. Recommendations from CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Chicago: American Society for Healthcare Engineering/American Hospital Association; 2004.

- US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Standard Interpretations. Most Frequently Asked Questions Concerning the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Available at: osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=I NTERPRETATIONS&p_id=21010#laundry. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hospital Acquired Infections: Sequence for Putting on Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Available at: cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/ppe/ PPE-Sequence.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2016.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2016;14(06):36,38,40–42.