Addressing Ulcerations of the Oral Cavity

Careful assessment of these common oral conditions is critical to ensure early detection of any malignant ulcerations.

This course was published in the August 2017 issue and expires August 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence, presentation, and etiology of common oral ulcers.

- Explain possible therapy and referrals when treating patients with oral ulcerations.

- List descriptive categories, risks, and common patient observations associated with these lesions.

Defined as a “circumscribed, craterlike lesion of the skin or mucous membrane resulting from necrosis that accompanies some inflammatory, infectious, or malignant processes,”1ulcers are a common finding in dental practice. The etiology of oral ulceration includes idiopathic, traumatic, viral, immune-mediated, and neoplastic causes. Cases of malignant ulcerations being inappropriately diagnosed as reactive or idiopathic lesions—rather than neoplastic lesions—have been reported, and delays in accurate diagnosis can lead to negative outcomes.2 As such, oral health professionals need to be able to successfully differentiate and triage oral ulcers in a timely manner.

APHTHOUS STOMATITIS

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), known colloquially as canker sores, is the most common cause of oral ulceration, affecting approximately 20% of the population,3 with a predilection in young individuals. Aphthous ulcerations are significantly less common in individuals age 50 and older. The etiology of RAS is unknown, but several immunological processes likely drive it. The cause can be divided into three primary categories: increased antigenic exposure, decreased mucosal integrity, and immunodysregulation.4 This condition includes a cell-mediated immune response, which involves tumor necrosis factor-α and T cells.5 While most patients with RAS cannot attribute onset to any definite cause, nutritional and metabolic factors may contribute to development of these lesions. Some of the more common predisposing factors include nutritional deficiencies (eg, vitamins B1, B2, B6, B12, iron, folate, and zinc); certain medications, chemical irritants, such as sodium lauryl sulfate, which is a common additive in toothpaste; and hormonal changes. In addition, RAS often manifests as a symptom of a systemic illness.5

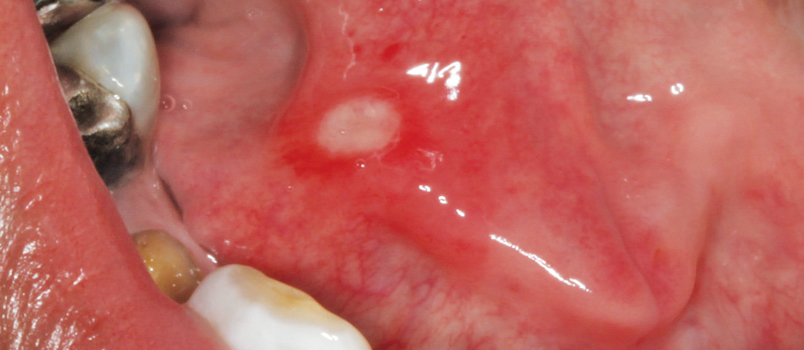

Clinically, RAS presents as painful, well-demarcated round ulcerations almost always involving the nonkeratinized lining mucosa of the oral cavity (Figure 1). They are classified based on clinical presentation. Morphologically, RAS lesions are categorized as minor aphthous ulcers, major aphthous ulcers, or herpetiform ulcers. Another classification system considers a patient’s overall episodes of RAS, dividing them into simple or complex aphthosis. Simple aphthosis is more common and involves fewer, quick-healing ulcers with minimal pain and disability. Complex aphthosis is less common and subject to frequent recurrence; it is characterized by constant presence of three or more aphthae that are associated with pain and disability.5

These ulcers can often be diagnosed on clinical grounds alone. The histology of RAS is not pathognomonic and these lesions present as an inflamed, ulcerated region with a fibrinopurulent membrane. Biopsy is rarely warranted because the clinical symptoms and signs are usually characteristic.4 The primary goal in managing RAS is to provide pain relief, shorten the length of each episode, and decrease the frequency of recurrence.6 A confident diagnosis is critical to management, especially in cases that are secondary to systemic illnesses or micronutrient deficiencies. Addressing systemic conditions predisposing patients to ulcerations, as well as eliminating any micronutrient deficiencies, is often enough to palliate RAS.6 In patients who are able to identify a definite causation, eliminating these triggers is helpful in preventing recurrence.

Localized treatment in the form of topical therapy is generally the first-line clinical response for idiopathic RAS. Over-the-counter remedies and topical anesthetics are usually sufficient for pain management. Other topical options include chlorhexidine rinse, aqueous minocycline, and topical corticosteroids. Aggressive therapy with systemic immunosuppressants and biologic agents should be reserved for severe cases.7 Patients with complex aphthosis usually require more elaborate evaluations and are managed by multidisciplinary teams of dentists, physicians, and other specialists.

TRAUMATIC ULCERATIONS

Traumatic ulceration of the oral mucosa is a common finding and usually attributable to sharp teeth, accidental biting, toothbrushing, or sometimes even talking. Trauma may also be due to thermal and chemical causes—often due to scalding food or drinks. These ulcerations may heal rapidly (acute), though some may persist for an extended period (chronic).4 Traumatic granuloma is one of the more significant traumatic ulcerations. Also known as traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia (TUGSE), these lesions present as long-standing oral ulcerations that are easily confused with oral squamous cell carcinoma.8,9 Most patients with TUGSE are older than 50, with equal gender distribution. Most frequently, it presents as a solitary lesion.9 The tongue is the most common location, although it may involve the lip, palate, gingiva, or floor of mouth.8 Riga-Fede disease involves a similar process that occurs in infants due to trauma of the ventral tongue from the primary anterior teeth.9

Traumatic ulceration is most frequently self-induced, usually from biting. The etiology of TUGSE, however is relatively unclear, as only 50% of cases demonstrate an association with trauma.8 The clinical features of a traumatic ulcer or thermal burn include areas of central ulceration with surrounding erythema. These ulcers affect the buccal mucosa and tongue, especially in areas of occlusal trauma, while thermal burns most commonly affect the palate (Figure 2). Significant pain is expected with thermal burns, but in some patients—particularly individuals with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy—a lack of pain may be evident.10

Traumatic ulceration is most frequently self-induced, usually from biting. The etiology of TUGSE, however is relatively unclear, as only 50% of cases demonstrate an association with trauma.8 The clinical features of a traumatic ulcer or thermal burn include areas of central ulceration with surrounding erythema. These ulcers affect the buccal mucosa and tongue, especially in areas of occlusal trauma, while thermal burns most commonly affect the palate (Figure 2). Significant pain is expected with thermal burns, but in some patients—particularly individuals with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy—a lack of pain may be evident.10

Presenting as a long-standing lesion, or as an ulcerated and indurated mass, TUGSE is often asymptomatic, but occasionally will present with pain. It commonly mimics oral squamous cell carcinoma in appearance and location.8 Often slow to resolve, TUGSE may be present for many weeks.11 Diagnosis is based on clinical history and biopsy results. Traumatic ulcers and thermal burns are usually readily diagnosed, and biopsy is indicated only if the clinical history isn’t consistent or they are nonhealing. Diagnosing TUGSE often requires a biopsy due to the lesion’s long duration and ominous appearance. Histologically, it presents as an ulcer with underlying, deeply penetrating inflammatory reaction that is heavily infiltrated with eosinophils.8

Management of traumatic ulcers and thermal burns is usually palliative, using over-the-counter topical anesthetics. These lesions tend to self-resolve within 1 week to 2 weeks.10 Antibiotics or antifungals are sometimes used to treat TUGSE if there is a superimposed infection. Removal of the inciting cause is necessary in cases in which trauma is suspected.11 An incisional or excisional biopsy is often performed to rule out a malignant process. Complete healing is common following a biopsy.

INFECTIONS

Viral infections are common causes of primary and recurrent oral and perioral ulceration. The Herpesviridae family is most often implicated, including human herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), human herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) and varicella zoster virus (VZV).12 Enteroviruses are another common cause of virally induced ulcerations and can result in herpangina and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD).

Most viral infections in the oral cavity are caused by HSV-1. The initial HSV-1 infection is generally self-limiting, and the virus establishes latency in the trigeminal ganglion. It can be periodically reactivated—triggers include cold, stress, trauma, dental procedures, and immunosuppression—leading to recurrent infections. While HSV-2 can also cause oral lesions, it is most commonly implicated with genital herpes. These viruses are transmitted via direct contact, often through saliva. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of VZV, which remains latent in cranial nerve or dorsal root ganglia.12

Herpangina is most commonly caused by coxsackie virus A1 to A6; however, other coxsackie viruses have been implicated. By comparison, HFMD is most commonly caused by coxsackie virus A16. Enterovirus 71 has also been implicated in both herpangina and HFMD.13 Clinically, HSV-1 can present as a primary infection or recurrent infection. Symptomatic primary HSV-1 infection involves fever, malaise, headaches, and lymphadenopathy. Patients may relay a history of intraoral vesicles involving the mucosa.14 Recurrent infections generally present as vesicular eruptions involving the lip vermillion. Intraoral HSV-1 infections most commonly affect keratinized mucosa, frequently involving the palatal surface, and present as multiple ulcerations that may coalesce together.

Varicella zoster virus has two clinical presentations. A primary varicella infection (ie, chickenpox) presents during childhood and is associated with generalized, pruritic maculopapular lesions. Recurrent infection with VZV is known as herpes zoster or shingles. It presents as unilateral vesicles that follow dermatomal distributions. Herpes zoster infections are associated with pain, tenderness, and paresthesia along the dermatome involved. Herpes zoster infections involving the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve put patients at risk of blindness. Patients are also at risk of post-herpetic neuralgia, a nerve pain that persists long after the cutaneous lesions resolve.12 Intraoral VZV presents on keratinized tissue, such as the palate, and is limited to one side. Their appearance is similar to that of HSV-1-induced lesions. Herpangina presents with oral ulcers involving the tonsillar pillars, soft palate, buccal mucosa, and uvula. Patients with HFMD have similar oral lesions, plus an exanthema involving the palms, soles, and knees.13

Although a presumptive diagnosis of virally induced ulceration can often be made based on history and clinical signs/symptoms, a viral culture is the gold standard for diagnosis.15 Viral cultures are not routinely ordered in clinical practice, however. A histologic examination of HSV-1-infected tissue will reveal classic cytopathic effects, with cells showing multinucleated giant cells, syncytium, and ballooning degeneration of the nuclei.12 Free-floating Tzanck cells are common. While the histology of VZV is identical to HSV, the histology of herpangina and HFMD is fairly nonspecific.4

The management of HSV-1 primarily consists of maintaining hydration, providing symptomatic relief, and the judicious use of antiviral medications. Antivirals, including acyclovir and valacyclovir, are best used during the initial stages of the lesions. Prophylactic antivirals can also be prescribed for patients who experience recurrent episodes or erythema multiforme secondary to HSV infection;12however, the efficacy of prophylactic antiviral regimens is debatable.

Treatment of herpes zoster in adults is aimed at reducing pain and preventing post herpetic neuralgia. Antiviral therapies are used at the earliest onset of symptoms (within 72 hours). Analgesics, such as opioids, may be cautiously prescribed for patients with moderate to severe pain. Corticosteroids are sometimes administered to reduce the likelihood of post herpetic neuralgia,15 which would be treated with neuropathic pain regimens, even after the illness has subsided.

Herpangina and HFMD are generally self-limiting infections. Treatment is directed at symptom palliation. Some clinics have used therapies—including intravenous immunoglobulin and ribavirin—for particular viral strains with success, but this is not routine practice.13

IMMUNE-MEDIATED

The immune-mediated classification includes a variety of conditions that frequently present with oral ulcerations. Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic inflammatory condition that potentially involves both the oral mucosa and skin. Most common in women, it affects between 0.5% and 2.0% of the population and generally manifests between the ages of 30 and 60.16 Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an autoimmune condition that affects mucous membranes in the oral, ocular, and genital areas. Generally affecting individuals between the ages of 60 and 80, the exact incidence of MMP is unclear, but some countries have exhibited an incidence of approximately 2.0 to 10.0 cases per million people.4

The etiology of LP is unknown, but genetic predisposition, stress, and trauma have been implicated. Lesions mimicking LP, known as lichenoid reactions, can arise due to reactions to medications or contact sensitivities, as well as a response to hematopoietic stem cell transplant known as graft-vs-host disease. As an autoimmune condition in which autoantibodies are directed against one of several proteins of the basement membrane zone of mucosal epithelium, it is not known what triggers the antibody response in patients with MMP.4

There are six clinical types of LP, with reticular and erosive/ulcerative subtypes considered the most common. The erosive pattern presents with erythema and areas of ulceration (Figure 3). This subtype is often associated with pain, as well as sensitivity to strong flavors. Reticular LP usually presents asymptomatically, with a white, lacy network known as Wickham striae—often involving the posterior buccal mucosa bilaterally (Figure 4).16 By comparison, MMP generally affects all aspects of the oral mucosa, and ocular involvement is not uncommon. Symblepharon eye lesions involving adhesions of the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva in patients with ocular manifestations of MMP can lead to scarring and blindness.17 This condition often manifests as erythematous, friable gingival tissue in a presentation known as desquamative gingivitis (Figure 5). Pemphigus vulgaris and erosive LP can present as desquamative gingivitis as well.18

A diagnosis of LP is made based on its clinical appearance and histologic findings. Erosive LP can appear similar to the other immune-mediated vesiculobullous conditions. Histologically, LP presents with saw-tooth rete ridges, hyperkeratosis, and a dense inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria.16 More specialized testing with direct immunofluorescence can further aid in the diagnosis of LP. Ulcerations caused by MMP are also diagnosed based on histopathologic findings and immunofluorescence results. Histologically, it exhibits a subepithelial split between the epithelium and lamina propria. Direct immunofluorescence testing of MMP will reveal subepithelial deposition of IgG, C3, and, sometimes, IgA.17

The goal of treatment is symptomatic relief with long periods of remission. The first-line treatment of erosive LP is topical corticosteroids. Mid-potency steroids (eg, fluocinonide), as well as potent steroids (eg, clobetasol), can be used topically.19Recalcitrant, localized lesions can be treated with intralesional steroid injections. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus) can also be used in refractory cases. Systemic immunomodulators—such as mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and methotrexate—are sometimes used in severe cases that cannot be effectively managed with topical therapy. The prognosis is good, although research has correlated LP with a slightly increased risk of malignant transformation, indicating the need for continued follow-up.16

In order to prevent blindness, patients with MMP should be referred to an ophthalmologist to rule out or manage ocular involvement.20 Management of oral lesions is directed at reducing pain and preventing scarring. In some cases, topical agents are all that is required for ulcers of the oral mucosa. Medication carriers can be fabricated for steroid drug delivery directly to the involved gingival tissue. Systemic medications are used for more generalized cases, and include dapsone, corticosteroids, azathioprine, methotrexate, tetracycline+nicotinamide, and mycophenolate mofetil. The prognosis for MMP is better than that for pemphigus vulgaris, and most patients are controlled with immunosuppressants. That said, MMP is a chronic condition and relapses and progression are common.18

CONCLUSION

Oral ulcers of long-standing duration require further investigation, especially if a definite cause cannot be ascribed. Usually, a biopsy of the affected tissue is sufficient for the initial work-up of a patient with an ulcer of questionable origin. Oral health professionals need to be aware that primary and metastatic malignant processes can also present as ulcers. Oral squamous cell carcinoma can manifest as a nonhealing ulcer, often involving the lateral tongue and floor of mouth (although it has numerous other clinical presentations).21An oral squamous cell carcinoma presenting as an ulcer often has rolled borders, induration, and pain,22 and may grow in an exophytic (outward) or endophytic (inward) fashion.21 Compared with other common causes of oral ulcerations, its etiology is vastly different and multifactorial. Identifying a malignant process is imperative, as the prognosis is fair, with an average 63% 5-year survival rate in the United States. In light of this, oral health professionals should be knowledgeable about the causes of oral ulcers and clinically capable of working up a patient with a nonspecific ulcer.

REFERENCES

- Mosby I. Mosby’s Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing & Health Professions. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier/Mosby; 2013.

- Mortazavi H, Safi Y, Baharvand M, Rahmani S. Diagnostic features of common oral ulcerative lesions: An updated decision tree. Int J Dent. 2016;2016:1–14.

- Shah K, Guarderas J, Krishnaswamy G. Aphthous stomatitis. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:341–343.

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders, Elsevier; 2016.

- Cui RZ, Bruce AJ, Rogers RS III. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:475–481.

- Ranganath SH, Pai A. Is optimal management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis possible? A reality check. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZE08–ZE13.

- Tarakji B, Gazal G, Al-Maweri SA, Azzeghaiby SN, Alaizari N. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis for dental practitioners. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:74–80.

- Joseph BK, BairavaSundaram D. Oral traumatic granuloma: report of a case and review of literature. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26:94–97.

- Hirshberg A, Amariglio N, Akrish S, et al. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia: a reactive lesion of the oral mucosa. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126:522–529.

- Kannan S, Chandrasekaran B, Muthusamy S, Sidhu P, Suresh N. Thermal burn of palate in an elderly diabetic patient. Gerodontology. 2014;31:149–152.

- Sarangarajan R, Vaishnavi Vedam VK, Sivadas G, Sarangarajan A, Meera S. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia—Mystery of pathogenesis revisited. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(Suppl 2):S420–S423.

- Balasubramaniam R, Kuperstein AS, Stoopler ET. Update on oral herpes virus infections. Dent Clin North Am.2014;58:265–280.

- Lee CJ, Huang YC, Yang S, et al. Clinical features of coxsackievirus A4, B3 and B4 infections in children. PloS One. 2014;9:e87391.

- Stoopler ET, Sollecito TP. Oral mucosal diseases: evaluation and management. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:1323–1352.

- Schmader K. Herpes zoster. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:539–553.

- Alrashdan MS, Cirillo N, McCullough M. Oral lichen planus: A literature review and update. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:539–551.

- Srikumaran D, Akpek EK. Mucous membrane pemphigoid: recent advances. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:523–527.

- Xu HH, Werth VP, Parisi E, Sollecito TP. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:611–630.

- Kurago ZB. Etiology and pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: an overview. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol.2016;122:72–80.

- Kim M, Borradori L, Murrell DF. Autoimmune blistering diseases in the elderly: Clinical presentations and management. Drugs Aging. 2016;33:711–723.

- Chi AC, Day TA, Neville BW. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma—an update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:401–421.

- Valente VB, Takamiya AS, Ferreira LL, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma misdiagnosed as a denture-related traumatic ulcer: A clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 2016;115:259–262.

Featured image by STEVANOVICIGOR/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2017;15(8):51-54.