Addressing Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis in the Dental Office

Oral health professionals play key roles in the diagnosis and management of this common viral infection.

This course was published in the December 2013 issue and expires 12/31/16. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- List the types of herpes simplex viruses.

- Describe the symptoms and clinical appearance of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.

- Discuss ways in which the transmission of herpes simplex viruses may be prevented.

- Recommend management options for patients affected by primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.

PATHOGENESIS

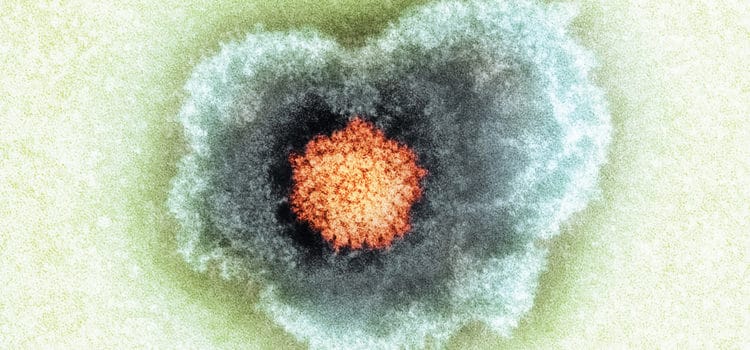

The initial outbreak of orofacial herpetic infections—regardless of which virus type causes the condition—is known as primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (PHG). This condition is diagnosed after an incubation period of 2 days to 2 weeks post-exposure.1,2 During this phase, the virus attacks various tissues in the oral cavity and may also affect the lips and perioral skin. The marginal gingiva appears erythematous throughout the maxilla and mandible, followed by the emergence of small vesicles on the gingiva, oral mucosa, tongue, and lips (Figure 1).2 These tiny fluid-filled lesions coalesce and rupture approximately 1 day to 2 days after manifestation, leaving behind ulcerations of various sizes. Systemic symptoms may accompany this condition as well. Fever, general malaise, pharyngitis, and submandibular and cervical lymphadenopathy are common occurrences with PHG.2,5,6 The healing time for this initial outbreak is approximately 2 weeks.2,7

After the initial stage of herpetic infection, the virus enters a latent phase, during which it migrates along sensory nerves and may take up residence in the trigeminal ganglion.2,8 Because there is no known cure for herpes simplex viruses, recurrent infections are common. Approximately 20% to 40% of individuals who experience PHG have recurrent outbreaks.2 Any condition that poses a threat to the immune system can trigger a reactivation of the dormant virus. Excessive sunlight exposure, illness, trauma, menstruation, and stress can all initiate outbreaks.1,2 Recurrent herpetic infections typically occur at the site of their initial entry into the body, which most often is the lips or perioral skin. Periodic outbreaks affecting these areas are referred to as herpes labialis.2,7

Similar to PHG, clustered vesicles appear during recurrent herpes simplex virus infections, although the gingiva is not typically affected. After the vesicles rupture, the ulcerations will form a scab, which can take up to 2 weeks to heal.2,7,8 The secondary outbreaks may be preceded by a prodromal phase (before the lesion begins to develop), in which the affected individual experiences tingling, itching, or burning sensations near the site of the impending lesion.2,7

Not all cases of herpes simplex virus are initiated with PHG. Many individuals experience a subclinical initial infection in which no detectable signs or symptoms are noted. Despite the absence of PHG, these individuals may still be prone to recurrent herpetic outbreaks. About 30% to 50% of the United States population is prone to periodic herpes simplex virus infections.7

TRANSMISSION

Herpes simplex viruses are highly infectious diseases that are spread through various avenues, such as close proximity to active lesions, mucosal secretions, or contaminated saliva.5,9 The disease is most contagious when a vesicular lesion is present, but studies show that many infected individuals shed the virus in saliva even when lesions are not clinically evident.1,5

Due to the potential for viral shedding and transmission via saliva, the dental team may be routinely exposed to herpes simplex virus infections in the form of aerosols or spatter. Aerosols in the dental office are produced by handpieces, air and water syringes, air-powder polishers, and ultrasonic scalers.8,10 This presents a high probability for transmission of the virus in the operatory. Prior exposure to the herpes simplex virus does not provide immunity or protection against subsequent exposures, so clinicians must be stringent followers of infection control practices to reduce the possibility of spreading disease in the clinical setting.8

People infected with HSV-1 can still be infected by HSV-2. Also, infected individuals can easily transmit the same virus to other areas of the body, such as the eyes (Figure 2), nose, fingers, or anywhere there is a break in the skin or mucosal lining. If the virus enters the skin of the fingers, a herpetic whitlow—a painful infection once common among dental professionals before standard infection control procedures were implemented—results (Figure 3).2 When the virus invades the eye, ophthalmic keratitis occurs.8 Both conditions can be debilitating.

The average age of onset for orofacial herpes simplex infections ranges from 6 months to 6 years.2,7 Research demonstrates that this trend may be shifting, with more adolescents and adults being diagnosed.6,11 Regardless of the age of onset, gender is not a factor in these infections.2

Due to the highly transmissible nature of HSV-1 and HSV-2, treating orofacially infected individuals in the dental office may pose risks to both patients and clinicians. Patients presenting with PHG or active secondary herpetic lesions should be rescheduled for treatment only after orofacial lesions are healed and no signs of active disease are present.2,4,7,8 In the event that emergency dental care is required during an outbreak of PHG or herpes labialis—in which rescheduling would cause undue harm to the patient—clinicians should stringently follow standard precautions and avoid aerosol production. Face shields used in conjunction with safety glasses with side shields are highly recommended during routine care of all patients. Risk of transmission of herpes simplex viruses is further limited when the amount of spatter that can potentially reach the face is reduced.2,8

DIAGNOSIS

A PHG diagnosis is reached by observing the clinical features and course of the lesions. PHG is similar to a variety of conditions, and care must be taken to differentiate them. While aphthous ulcers may exhibit similar symptoms, these lesions typically present as single ulcerations on nonkeratinized mucosa and do not appear as coalescing groups. Additionally, there is never a vesicular stage.2 Herpes zoster, or shingles, is the reactivation of the varicella zoster, or chickenpox, virus, and is not PHG. This herpetic infection is typically seen in older adults, whereas PHG most often presents in children, adolescents, or young adults. Occasionally, this infection may produce intraoral lesions that resemble those of PHG. Herpes zoster lesions, however, typically present unilaterally, following the affected nerve tract.2

Necrotizing gingival conditions can initially be mistaken for PHG because they also present with ulcerative lesions on the gingiva. The characteristic cratered appearance of the necrotizing gingivitis or periodontitis, however, may be reserved to the interdental papillae, whereas PHG affects all areas of the gingiva. These conditions also demonstrate a rapid course of progression, with considerable tissue destruction occurring in as little as 3 days. As the necrotizing condition progresses, the papillae take on a punched-out appearance, and a fetid odor and severe pain persist.12

Herpangina and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) can both resemble PHG. Although fever, malaise, and other flulike symptoms may occur with herpangina, the intraoral vesicular lesions are confined to the soft palate and disappear in less than 7 days. In HFMD, oral lesions may be present and are accompanied by vesicles on the hands, feet, and/or elsewhere on the body.7

Erythema multiforme, which is caused by a herpes simplex virus infection in 70% to 80% of cases, may also manifest as intraoral lesions and inflammation. Not to be confused with PHG, the characteristic presentation of erythema multiforme is target lesions of concentric erythematous rings alternating with normal skin color. These lesions are typically found on the trunk and extremities. Patients will also frequently experience crusting and bleeding of the lips, which may look similar to a severe case of PHG with perioral lesions. Erythema multiforme is also a self-limiting infection that lasts 3 weeks to 6 weeks. Medication use has also been implicated as a causative factor in this disease. As such, patients should be questioned regarding recent medication use, as well as previously known exposures to herpes simplex viruses.13

EDUCATION

Patient education is critical in the management of PHG and subsequent outbreaks. Oral health professionals should carefully explain to patients with an outbreak of PHG or other active herpetic lesions that dental treatment can promote the spread of infection to other areas of the mouth, lips, nose, or eyes, as well as to other people. Clinicians are prone to infection or re-infection, as are other patients.14

Lamey and Biagioni15 demonstrated that infected individuals had a good grasp in recognizing herpes simplex virus outbreaks, or “cold sores,” but only half were aware that the lesions were caused by a virus. Patients need to understand the infectious nature of the disease, as well as the risk of spreading infection to other individuals—even in the absence of clinically evident lesions. They should be instructed to refrain from touching sores, limit interpersonal contact, and practice meticulous hand hygiene during outbreaks.14 Frequent and thorough handwashing effectively removes traces of virus particles on intact skin, as herpes simplex viruses are sensitive to soap and warm water.8

Individuals with PHG, because of the painful nature of the virus, may refrain from eating and drinking during the initial outbreak. Both children and adults should be instructed on maintaining proper hydration during this period.16 Not all patients, however, will experience the typical moderate to severe pain that accompanies PHG, and other symptoms of the initial infection may also be limited or absent. The strain of herpes simplex virus, as well as the host response, may contribute to the increased severity of signs and symptoms in individual cases.4

MANAGEMENT

In order for primary infections to become symptomatic, the virus must penetrate through epithelial cells, replicate, and cause cell destruction. In turn, neighboring cells may also be affected by the replicating virus. The body’s natural inflammatory response, initiated by the presence of the replicating virus, also contributes to the disease process. This sequence of events may dictate the severity of infection observed.4 Adults with PHG, however, will often present with more severe symptoms than children. Fever reducers or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be recommended for relief of fever, pain, and discomfort.16 In addition, patients may find temporary relief by applying a topical remedy of a 50% Benadryl elixir and 50% loperamide liquid (a common antacid and antidiarrheal medication) onto the PHG sores.2 Applying ice may also provide some temporary relief of pain and inflammation.14 A recent study also suggests that a monocaprin and low-dose doxycycline gel may prove effective in reducing pain and healing time in herpes labialis.6 Dental professionals should remain up to date on the results of such studies in order to best advise their patients.

Over-the-counter lip balms may lessen the symptoms and severity of lip and perioral lesions. Docosanol 10% ointment can be applied every 2 hours, beginning in the prodromal phase. Application may continue until the lesion has healed.14 Ointments containing L-lysine, zinc oxide, and herbal combinations have also proven effective in treating cold sores. In a small study, this particular blend of ingredients demonstrated a significant reduction in lesion healing time.17 Products containing benzalkonium chloride are also available, but more research is needed to support their efficacy and safety. The use of salicylic acid in the treatment of lip and perioral lesions, however, may cause more damage to the tissues during outbreaks, depending on the concentration.18

When using lip balms or other topical remedies, patients should be advised against using their bare fingers to apply the ointment to minimize the risk of spreading the infection. Single-use cotton tip applicators, finger cots, or disposable gloves should be utilized when applying topical ointments.2

Palliative treatment of PHG should also include temporary diet modification. Patients should maintain a nonacidic diet of soft, cold foods and noncarbonated beverages.2 Avoiding spicy foods during oral outbreaks is also good practice.

ANTIVIRAL AGENTS

The use of antiviral agents in treating PHG is controversial. PHG and subsequent herpes simplex virus outbreaks are self-limiting infections. Additionally, some studies have indicated that antivirals are not helpful in treating PHG. For these reasons, systemic antiviral therapy is often unwarranted.19 Topical acyclovir (5%) cream, however, may be effective in treating recurrent herpes labialis.20

The use of antiviral therapy for PHG or recurrent herpes labialis is most efficacious if administration begins during the prodromal phase, or within the first several hours of observing a clinical sign of the infection. This is when viral replication is at its highest point and the efficacy of antiviral medications will be maximized. Because the virus stops replicating after approximately 48 hours, the administration of antiviral therapy after this point may not be useful.20 Patients should monitor themselves for prodromal symptoms so treatment can begin immediately. This is especially important among those who have experienced severe PHG or subsequent orofacial herpes simplex virus outbreaks.

Immunodeficient individuals may have an exaggerated response to initial and subsequent herpes simplex virus outbreaks. Patients undergoing chemotherapy, who have received organ transplants, or been infected by the human papillomavirus will benefit most from systemic antiviral medications. The lack of immune response may trigger more frequent and more severe symptomatic lesions, which may be present for a longer duration than in immunocompetent individuals. Systemic antiviral medications may reduce the morbidity and mortality rates due to HSV-1 infections in immunocompromised individuals. In these cases, systemic antiviral therapy should be considered for routine administration to limit the potentially severe effects and to further reduce the spread of infection. Antiviral therapy prescriptions are recommended for short-term use only, however, to hinder the development of drug-resistant strains of herpes simplex viruses.20

POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Dehydration is a frequent complication of PHG, especially in severe cases of intraoral or perioral pain and inflammation.16 However, the potential for more serious complications exists. In rare instances, viral infections have been implicated in cases of viral encephalitis. Of the 100 or more viruses that have been proposed as causative agents, HSV-1 is the most frequent, and has also been implicated in many of the most severe cases.21

Viral encephalitis occurs when the infection causes inflammation in the brain. While some cases may be mild, this condition has the potential to progress rapidly. In rare cases, viral encephalitis can be fatal. Signs and symptoms of this condition include fever, headache, and altered consciousness.21 Patients with PHG should be advised to monitor themselves for any progression of current symptoms, and to seek immediate medical attention if their condition deteriorates or signs of viral encephalitis develop.

PERIODONTAL CONNECTIONS

Recent studies suggest that several human herpes viruses may contribute to the overall presence and destructive nature of periodontal diseases; however, this assumption is currently under debate.9,22 Epstein Barr, human cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex viruses have all been identified in samples of crevicular fluid extracted from periodontal pockets of patients with chronic periodontitis. Patients who had human herpes simplex viruses in their periodontal pockets demonstrated deeper probe readings and greater severity of disease.9 This particular pattern of periodontitis may be due to the effects of herpes simplex viruses on various cells that contribute to immune function. HSV-1 has been found in T-lymphocytes and macrophages, among other cells, in tissue samples of patients with periodontal diseases.9 As HSV-1 has destructive capabilities in cells, this may suggest that there is a disruption in the normal immune function of periodontal tissues, and, thus, an increase in severity of damage to the periodontium due to the presence of HSV-1 and other human herpes viruses.9,23

Patients with PHG should be advised of this potential link. Meticulous oral hygiene should be encouraged for any patient with known herpes simplex virus infections to prevent the risk of severe periodontal diseases.

CONCLUSION

The clinical appearance, symptoms, and general morbidity of PHG prompt many individuals to seek the assistance of dental professionals in diagnosing the condition. Dental hygienists are often the first clinicians to encounter individuals with these active viral infections, thus, they should be able to perform a differential diagnosis based on key features of PHG in relation to other infections and diseases that present with similar clinical symptoms. Due to the highly infectious nature of this disease—and the potential for extreme discomfort and more severe complications—oral health professionals must be aware of the steps necessary for proper detection and management of orofacial herpes simplex viruses at all stages.

References

- Christie SN, McCaughey C, Marley JJ, Coyle PV, Scott DA, Lamey PJ. Recrudescent herpes simplex infection mimicking primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:8–10.

- DeLong L, Burkhart NW. Lesions that have a vesicular appearance. In: General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013:305–330.

- Grinde B. Herpes viruses: latency and reactivation—viral strategies and host response. J Oral Microbiol. 2013;5:22766.

- Pithon MM, Andrade ACDV. Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis in an adult patient using an orthodontic appliance. Int J Odontostomat. 2010;4:157–160.

- Tovaru S, Parlatescu I, Tovaru M, Ciona L. Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis in children and adults. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:119–124.

- Skulason S, Holbrook WP, Thormar H, Gunnarson GB, Kristmundsdottir T. A study of the clinical activity of a gel combining monocaprin and doxycycline: a novel treatment for herpes labialis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:61–67.

- Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA. Infectious diseases. In: Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 5th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:118–153.

- Browning WD, McCarthy JP. A case series: herpes simplex virus as an occupational hazard. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24:61–66.

- Das S, Krithiga GS, Gopalakrishnan S. Detection of human herpes viruses in patients with chronic and aggressive periodontitis and relationship between virus and clinical parameters. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:203–209.

- Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- Katz J, Marmary I, Ben-Yehuda A, Barak S, Danon Y. Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis: no longer a disease of childhood? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:309.

- Rathe F, Chondros P, Chistodoulides N, Junker R, Sculean A. Necrotising periodontal diseases. Perio. 2007;4(2):93–107.

- Samim F, Auluck A, Zed C, Williams PM. Erythema multiforme: a review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:583–596.

- Stoopler ET, Kuperstein AS, Sollecito TP. How do I manage a patient with recurrent herpes simplex? J Can Dent Assoc. 2012;78:c154.

- Lamey PJ, Biagioni PA. Patient recognition of recrudescent herpes labialis: a clinical and virological assessment. J Dent. 1996;24:325–327.

- Thomas E. A complication of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Br Dent J. 2007;203:33–34.

- Singh BB, Udani J, Vinjamury SP, et al. Safety and effectiveness of an L-lysine, zinc, and herbal-based product on the treatment of facial and circumoral herpes. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10:123–127.

- Pray WS. Preventing and treating cold sores. US Pharmacist. 2007;32(3):16–23.

- Porter SR. Little clinical benefit of early systemic aciclovir for treatment of primary herpetic stomatitis. Evid Based Dent. 2008;9:117.

- Arduino PG, Porter SR. Oral and perioral herpes simplex virus type I (HSV-I) infection: review of its management. Oral Dis. 2006;12:254–270.

- Téllez de Meneses M, Vila MT, Barbero Aguirre P, Montoya JF. Encefalitis virales en la infancia. Medicina (B Aires). 2013;73(Suppl 1): 83–92.

- Stein JM, Said Yekta S, Kleines M, et al. Failure to detect an association between aggressive periodontitis and the prevalence of herpes viruses. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:1–7.

- Hung SL, Chiang HH, Wu CY, Hsu MJ, Chen YT. Effects of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection on immune functions of human neutrophils. J Periodont Res. 2012;47:635–644.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2013;11(12):52–56.