Working to Improve Access to Care

Community health centers play a vital role in improving the health and quality of life of disadvantaged patient populations.

This course was published in the June 2014 issue and expires June 30, 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define what is a community health center.

- Identify the populations served by community health centers.

- Discuss the importance of medical/dental homes.

- Explain the importance of oral health in chronic disease management.

- Detail the role of dental hygienists in serving disadvantaged populations through community health centers

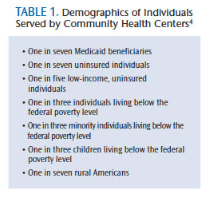

Community health centers are nonprofit, community-directed, and federally designated providers of health care that serve more than 22 million Americans.1,2 They provide health care services to the uninsured, working poor, and newly jobless who face financial, geographic, language, and cultural barriers to accessing medical and dental services (Table 1).2–4 Community health centers provide comprehensive primary health services, dental care, specialty services, prescriptions for medications, and case management to more than 9,000 communities1 in more than 1,200 physical locations.2,5 Care is provided regardless of individuals’ insurance status or ability to pay.

Since the inception of the nation’s first community health centers in 1965, they have become a vital portal for health care services for the medically underserved, high-risk, and uninsured populations in the United States.1,3,6,7 These vulnerable individuals are able to receive primary and preventive health care and oral health services.3,7,8 Traditionally, care that was provided at community health centers emphasized disease treatment and management.3,7,8 Today, many community health centers serve as primary medical and dental homes focused on disease prevention, health promotion, and the reduction of disparities among those disproportionately burdened by chronic illnesses.3,6,9

IMPORTANCE OF THE MEDICAL/DENTAL HOME

Medical and dental homes offer patients an opportunity to establish an ongoing relationship with a team of health care providers.1,5,7 The majority of patients enter the health care system at the primary care level.3,10 Unfortunately, some use emergency departments inappropriately for routine care, chronic condition management, and relief of oral pain. The most effective health services are disease prevention and health promotion. Patients who do not have a primary medical or dental home are subject to delayed, inaccessible, and unaffordable care.3,11 This, in turn, decreases health status; impacts the need for nonurgent hospital stays; and increases overall health care spending at the individual, community, system, state, and national levels.3,11

Medical and dental homes offer patients an opportunity to establish an ongoing relationship with a team of health care providers.1,5,7 The majority of patients enter the health care system at the primary care level.3,10 Unfortunately, some use emergency departments inappropriately for routine care, chronic condition management, and relief of oral pain. The most effective health services are disease prevention and health promotion. Patients who do not have a primary medical or dental home are subject to delayed, inaccessible, and unaffordable care.3,11 This, in turn, decreases health status; impacts the need for nonurgent hospital stays; and increases overall health care spending at the individual, community, system, state, and national levels.3,11

The National Association of Community Health Centers is actively working to increase capacity for primary care at the community level for the medically underserved.2,5 Efforts are underway to strengthen existing programs and to develop new programs, with the goal of reaching 40 million patients by 2015.2 This restructuring is designed to increase competitiveness in a cost-sharing health insurance industry and create a more transparent exchange in which care coordination will improve, health literacy will grow, access to preventive measures will increase, fraud and waste will decrease, overpayment for service will decline, and quality will be the standard.12

NEW ROLE OF COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS

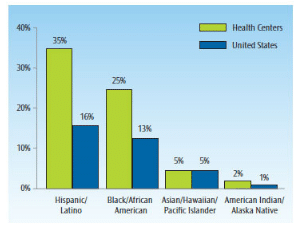

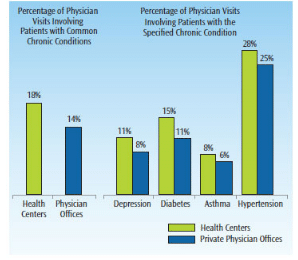

In establishing their new roles with the passing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, community health centers are expanding their service delivery models to take a new approach to providing resources, education, and health promotion.13 Community health centers have initiated several cost-effective and resource-sharing projects to better address the access-to-care needs of their patient populations. Some of these projects are specifically designed for improving health outcomes among minorities (Figure 1),4,14 and those with chronic diseases,5 such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, obesity (Figure 2),4,13 and oral health problems.15 Community health centers strive to achieve a seamless continuum of high-quality health care delivery that is accessible and affordable for surrounding geographical community residents.3 Because community health centers partner with other service organizations to improve the overall coordination and navigation of care for the area’s underserved populations, they serve as community builders and agents for change.3,14 Community health centers have taken a lead role in establishing programs to assist patients with eligibility screening and enrollment for health insurance programs,5 prescription medication access,4 and oral health prevention services.15

Community health centers are unique for several reasons. By virtue of their federal qualifying status, they are located in communities with limited accessibility to quality, comprehensive care. They are required to provide both medical and preventive dental services. Preventive dental services are to be provided on site. If this is not possible, care will be arranged via referral. With multisite community health centers, at least one location must offer preventive dental care services. The centers are further required to address barriers that may impede the underserved populations of their geographically assigned location. To meet this requirement, they offer such supplementary services as case management, transportation, culturally appropriate linguistic translation, outreach,15 and health education.3 Community health centers are also becoming silos of data, which are vital to health services researchers, economists, health insurance analysts, policymakers, and other safety-net providers.1

The efforts of community health centers are focused on the needs of patients in their geographic area, and they work with local establishments to increase care coordination.5 To integrate a message of oral health promotion and prevention, community health center management will need to increase collaboration with oral health professionals to bolster their knowledge of the link between oral health and systemic health, and to create successful strategies for health promotion and disease prevention that include comprehensive health plans.15

Community health centers are also uniquely positioned not only to improve health outcomes but also to impact health literacy among those they serve.15 Research shows that increasing health literacy is key to improving patient outcomes.16–18 Strategies for growing health literacy include providing information to the public on how to access services, making those services accessible and affordable, limiting existing and potential barriers, and offering a comprehensive service delivery model that includes medical and dental services.

INTEGRATING ORAL HEALTH INTO COMMUNITY CARE CONTINUUM

Oral disease is a major public health issue. Disadvantaged and underserved populations experience the greatest burden of oral diseases. The relationship between oral health and general health is well documented.19 One of the Healthy People 2020 Objectives is to add oral health components to more community health centers.20

Oral health is linked to the pathogenesis of many systemic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain respiratory problems. The oral biofilm associated with severe periodontal diseases is a potential source of systemic inflammation, releasing inflammatory mediators that worsen systemic health problems. In addition, systemic diseases may negatively impact oral health. These diseases can lead to increased risk of oral conditions, such as xerostomia, tooth mobility, gingival overgrowth, oral pain, and bone resorption.21

The high prevalence of polypharmacy therapies, especially among older adults, may further complicate the impact on oral health status.22 Other risk factors that negatively impact oral health include diets high in fermentable carbohydrates and abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs.

Dental caries and periodontal diseases are two of the most problematic chronic diseases affecting individuals worldwide. They can be prevented and treated effectively through interprofessional cooperation with administrators and stakeholders of community health centers.23

CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT

Clinical research supports a relationship between diabetes and poor oral health.22 Findings show that patients with diabetes are more likely to develop periodontal diseases, as well as exhibit high levels of cariogenic bacteria. Patients diagnosed with diabetes are at increased risk of root surface caries; decayed, missing, or filled teeth; and increased levels of plaque. Reduced salivary flow—which is impacted by neurosensory conditions, such as dysphaghia, fungal lesions, bacterial flora, and neuropathy—is another common problem.

Health education for individuals with diabetes is integral to the prevention of morbidity and mortality associated with chronic diabetes. Clinicians must stress the importance of positive oral health habits and their implications for improving overall diabetes management. Many patients do not perceive oral health as important; therefore, they may not engage in self-care regimens that include regular brushing and flossing. In addition, disadvantaged populations often do not have access to consistent care. The primary care medical home has a responsibility to partner with dental hygienists to deliver health messages about the relationship of care management for diabetes and improved oral hygiene.23

Cardiovascular diseases account for 30% of deaths in the US annually. Approximately 47% of adults older than 30 have some form of periodontal disease, and 64% of adults older than 65 have moderate to severe periodontitis.24 C-reactive protein, which plays an important role in periodontal disease development, is a type of plasma protein produced by macrophages, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle that is present during episodes of acute inflammation or infection, and is a predictor for cardiovascular disease risk.

Poor oral health may also be related to miscarriage, preterm birth, low-birth-weight, and preeclampsia.25 Some research shows that the presence of periodontal diseases during the second trimester of pregnancy may increase the risk of preterm births, but the evidence is mixed. Bacteria associated with periodontal diseases may also retard fetal growth, possibly inducing adverse pregnancy outcomes.26 Additional risk factors include smoking, alcohol use, poor diet, and stress.

Epidemiologic studies strongly suggest a relationship between periodontal diseases and certain respiratory diseases, particularly in frail older adults and those residing in long-term care facilities. Oro-pharyngeal pathogens may lead to respiratory infections.27

To help individuals manage obesity and chronic conditions that require improved diet and nutrition, community health centers are starting to offer increased access to healthy food choices.13 Grocery stores, farmer’s markets, and community gardens are now part of the service delivery plan for primary health care at the community level because nutrition-related conditions are more prevalent among those who have limited access to healthy food choices. These individuals are concentrated among communities of lower socioeconomic status and minorities.13

Increased rates of tooth loss are reported among those who are older and obese.27 The presence of tooth loss impairs individuals’ ability to masticate food. A limited number of teeth impacts effective processing of food in the oral cavity, and those with tooth loss are more likely to choose foods that are low in nutritional value.24,28

THE ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

Despite current efforts to provide comprehensive health care (including oral health services) to disadvantaged populations, there are gaps in care. To meet the demanding and necessary changes of the current health care system, health professionals are working to revamp and transform their educational curricula. In 2011, a visionary panel of experts from several disciplines of health education developed core competencies for interprofessional educational collaborative practice to prepare students entering the workforce to practice efficient team-based care. This paradigm shift in health care education will positively impact community health centers by helping health professionals not only practice to their full scope of knowledge but also foster cooperative efforts of patient-centered care.29

In response to the increasing needs of patients and the growth of alternative practice settings, dental hygienists are well suited to collaborate with all types of health providers. Closely following advanced nursing models, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association and the American Dental Association have responded with new types of oral health care providers. The advanced dental hygiene practitioner’s scope of practice goes beyond that of the traditional dental hygienist to provide care without on-site supervision. Several states are currently considering proposals for dental hygienists to pursue additional education to expand the traditional scope of practice. Minnesota and Maine have passed legislation allowing mid-level practitioners to deliver care.

Community health centers not only help meet the growing demand for health services among the underserved and uninsured, but they also create jobs. From expanded clinical scope of practice to management to program development, dental hygienists are a perfect match to link practitioners who provide oral health care with those who supply medical services.

CONCLUSION

Community health centers are the safety net for the medically and dentally underserved populations who often exhibit chronic conditions, social issues, economic problems, and health disparities.1 These centers seek to reduce the racial/ethnic health disparities of the medically underserved by increasing access to quality care, promoting prevention, and improving health outcomes.1

Most important, community health centers provide assessments and develop corresponding plans to meet the needs of patients and the local community. The diverse populations served by these centers require that they work to eliminate the disparities in health care access by offering a more comprehensive health care delivery model.3 Dental hygienists are well positioned to help community health centers achieve these goals.

As part of the greater health care community, oral health professionals should be part of efforts to help patients effectively manage chronic conditions and assist in cultivating healthy environments to prevent premature morbidity, increase quality of life, and reduce the risk of disability. To effectively serve diverse communities, creative thinking that encompasses practical applications, novel interventions, accessibility, and affordability is key.

Expanding health care providers’ roles to offer more comprehensive services at the primary care level is necessary.30 Combining the efforts of medical and dental care coordination and delivery may also better serve patients.30 Education and health promotion can be achieved by involving dental hygienists and primary care providers.28 Research on health outcomes has illustrated the need for primary care providers to become skilled in assessing oral health status.15

The time to form coalitions between those who prevent and treat oral diseases and those who prevent and treat systemic diseases is now. Community health centers are well suited to bridge this gap.

REFERENCES

- Boutin-Foster C., Scott E, Melendez J, et al. Ethical considerations for conducting health disparities research in community health centers: a social-ecological perspective. Am J Public Health. 2013;103: 2179–2184.

- National Association of Community Health Centers. Community health centers lead the primary care revolution. Available at: nachc.com/client/documents/Primary_Care_Rev olution_Final_8_16.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2014.

- Shepherd JG, Locke E, Zhang Q, Maihafer G. Health services use and prescription access among uninsured patients managing chronic disease. J Community Health. 2014;39:572–583.

- National Association of Community Health Centers. A Sketch of Community Health Centers Chart Book 2013. Available at: nachc.com/client//Chartbook2013.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2014.

- The Nation’s Health. Community health centers lead health insurance enrollment: Implementing the Affordable Care Act. Available at: thenationshealth. aphapublications.org/content/44/1/1.1.full. Accessed May 22, 2014.

- Flinter M. Residency program for primary care nurse practitioners in federally qualified health centers: a service perspective. Online J Issues Nurs. 2005;10:6.

- Rust G, Baltrus P, Ye J, et al. Presence of a community health center and uninsured emergency department visit rates in rural counties. J Rural Health. 2009;25:8–16.

- Samuels M, Xirasagar S, Elder KT, Probst JC. Enhancing the care continuum in rural areas: survey of community health center-rural hospital collaborations. J Rural Health. 2008;24:24–31.

- Gold R, Devoe J, Sha A, Chauvie S. Insurance continuity and receipt of diabetes preventive care in a network of federally qualified health centers. Med Care. 2009;47:431–439.

- Corrigan MG, Greiner A, Erikson SM, eds. Fostering Rapid Advances in Health Care: Learning from System Demonstrations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.

- O’Fallon L, Dearry A. Community-based participatory research as a tool to advance environmental health sciences. Environmen Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 2);155–159.

- Rosenbaum S. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:130–135.

- Freedman DA, Whiteside YO, Brandt HM, Young V, Friedman DB, Hebert JR. Assessing readiness for establishing a farmers’ market at a community health center. J Community Health. 2012;37:80–88.

- Parrill R, Kennedy BR. Partnerships for health in the African American community: moving toward community-based participatory research. J Cult Divers. 2011;18:150–154.

- Jones E, Shi L, Hayashi AS, Sharma R, Daly C, Ngo-Metzger Q. Access to oral health care: the role of federally qualified health centers in addressing disparities and expanding access. Am J Public Health. 2013;103;488–493.

- Kountz DS. Strategies for improving low health literacy. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:171–177.

- Nichols-English G. Improving health literacy: a key to better patient outcomes. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2000;40:835–836.

- Street RL Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301.

- Ciancio SG, Scannapieco FA. PDR Clinical Handbook on Oral-Systemic Health. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare; 2008:15–28.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. HealthyPeople.gov. Healthy People 2020: Topics and Objectives: Oral Health. Available at: healthypeople.gov/ 2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topic id=32. Accessed May 22, 2014.

- Scully C, Ettinger RL. The influence of systemic diseases on the oral health care in older adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(Suppl):7S–14S.

- Sheiham A, Watt RG. The common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:399–406.

- Kanjirath PP, Kim SE, Rohr Inglehart M. Diabetes and oral health: the importance of oral health-related behavior. J Dent Hyg. 2011;85:264–272.

- Eke P, Dye BA, Wei L, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91:914–920.

- Jeffcoat MK, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Goidenberg RL, Hauth JC. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: results of a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:875–880.

- Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:70–78.

- Scannapieco FA. Role of oral bacteria in respiratory infection. J Periodontol. 1999;70:793–802.

- Griffin SO, Jones JA, Brunson D, Griffin PM, Bailey WD. Burden of oral disease among older adults and implications for public health priorities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:411–418.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice. Available at: asph.org/userfiles/collaborativepractice.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2014.

- Cohen LA. Expanding the physician’s role in addressing the oral health of adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:408–412.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2014;12(6):60–64.