Periodontal Risk Management

Assessment and identification of specific risk factors are integral to a comprehensive periodontal examination.

This course was published in the June 2014 issue and expires June 30, 2017. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe models for risk assessment in dental patients.

- Discuss the simple model for management of risk factors in dental patients.

- Integrate management of risk factors into clinical practice.

Abundant evidence supports the role of specific risk factors in periodontal disease prevalence, severity, progression, and treatment outcomes. Therefore, a comprehensive periodontal examination is not complete without evaluation and identification of specific risk factors affecting the patient’s condition. Risk factor assessment is an important part of long-term periodontal care and health, and dental hygienists—who assess, manage, and modify these risk factors—play a key role in this process. This article will provide a simple model for the comprehensive management of periodontal risk factors in clinical practice, which remains a major component of successful long-term periodontal care.

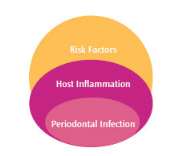

Periodontal diseases are bacterial infections with subgingival pathogens responsible for the disease process. This subgingival infection, which is specific and unique to the oral cavity, is not sufficient for the tissue destruction to take place. An increased host inflammatory response to the bacterial infection and particular risk factors that modulate the host’s inflammatory response are necessary for the disease to manifest clinically.1–3 The triad of periodontal infection, host inflammatory response, and associated risk factors are the core of the multifactorial nature of periodontal diseases (Figure 1).

RISK ASSESSMENT

Recognition that the presence of specific risk factors is necessary for periodontal disease development has placed considerable importance on risk assessment—and resulted in a paradigm shift in the diagnosis and treatment of a disease once understood to be directly related to dental plaque.4 As a result, the role of risk assessment in clinical dentistry has become increasingly important and is now considered a vital aspect of clinical practice. Documentation of systemic and local risk factors alongside the diagnosis in patients’ case records is recommended.

Practicing risk assessment, or focusing on the early identification and prevention of periodontal diseases, affords oral health professionals the opportunity to improve patients’ dental and medical outcomes. The use of formal risk assessment tools assists clinicians in identifying patients at greatest risk for periodontal diseases and those in need of targeted interventions to prevent or reduce the severity of disease. Managing and preventing risk for developing periodontal diseases is relatively new to the dental profession. Some models have been proposed to help dental professionals obtain and integrate risk assessment information into daily practice.

MODELS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

In recent years, numerous computer-generated risk assessment models have been proposed to assist oral health professionals with estimating patients’ risk of periodontal diseases, and from which risk assessment may be implemented in clinical practice. Internet-based systems are available that quantify risk for periodontitis and periodontal disease severity and extent, and generate treatment recommendations and interventions. They typically gather clinical and radiographic data that are combined with medical and risk factor information. After data analysis, risk and disease scores may be generated, along with suggested treatment modalities.5,6 Other Web-based tools use mathematical algorithms to calculate risk based on risk factors, such as: age; history of smoking, diabetes, and periodontal surgery; pocket depth; furcation involvement; alveolar bone height; and vertical bone loss.6 Risk scores increase depending on history of periodontal surgery, tobacco use, and presence of chronic disease.7

Another periodontal risk assessment tool uses a functional diagram to evaluate the risk for progression of periodontal diseases.8 Included in this diagram to assess risk are percentage of bleeding on probing sites; prevalence of residual pockets greater than 4 mm; loss of teeth (excluding third molars); loss of periodontal support relative to patient age; systemic and genetic conditions; and environmental factors (eg, smoking). The contribution of each risk factor domain is arbitrarily weighed to yield an overall risk score and a visual representation of the patient’s individual risk of progression of periodontal disease. This method has not been validated prospectively, however, and its use is limited to a patient discussion and motivational tool.

Another periodontal risk assessment tool uses a functional diagram to evaluate the risk for progression of periodontal diseases.8 Included in this diagram to assess risk are percentage of bleeding on probing sites; prevalence of residual pockets greater than 4 mm; loss of teeth (excluding third molars); loss of periodontal support relative to patient age; systemic and genetic conditions; and environmental factors (eg, smoking). The contribution of each risk factor domain is arbitrarily weighed to yield an overall risk score and a visual representation of the patient’s individual risk of progression of periodontal disease. This method has not been validated prospectively, however, and its use is limited to a patient discussion and motivational tool.

The American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) self-assessment tool uses a 13-item questionnaire to gather patient data regarding patient age, flossing behavior, history of smoking, diabetes, heart disease, osteoporosis, and high stress. Using an algorithm, the answers are combined and categorize patients as either low risk, medium risk, or high risk. This self-assessment system enables the estimation of periodontal disease risk for the general population.9

SIMPLIFIED MODEL FOR CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF PERIODONTAL RISK FACTORS

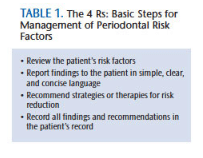

A simple, evidence-based model for implementing periodontal disease risk assessment and management is proposed. It can be altered as therapies and goals evolve. This simple model can be integrated into clinical practice and applied at each dental visit, and it does not require additional appointment time. These steps—review, report, recommend, and record, collectively referred to as the “4 Rs”—are already part of the periodic dental/periodontal examination (Table 1). While not new, this model is organized in a coherent sequence that ensures a concrete outcome—and can be implemented into practice without reducing time spent on other components of dental care while enhancing the scope of the visit.

![Periodontal Disease]() REVIEW

REVIEW

The first step in managing patients’ risk factors is to review them. Current risk factors may be elicited on patient questionnaires that include a section for medical conditions (and resulting systemic risk factors), including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, and autoimmune diseases. Questions regarding established periodontal risk factors should be integrated into existing patient questionnaire systems. Dietary habits and use of nutritional supplements, alcohol, and tobacco should also be noted on this form. Information obtained in the patient questionnaire should be reviewed with the patient.

REPORT

The report step focuses on making patients aware of their risk factors and risk profile. Patients should be educated about the factor(s) for which they are positive and how it impacts periodontal conditions and treatment outcomes. Summarize this information in simple language that is easily understood. Following this step is crucial, as it allows establishment and reaffirmation of the dental professional/patient relationship and builds trust.

During this report, provide patients with information on the oral-systemic link that better explains the interconnectedness of oral and general health. Providing this information leads into the next phase—recommend—which discusses what patients can and/or should do in order to reduce their risk for periodontal diseases.

RECOMMEND

Recommend strategies for reducing risk. Using brief and concise language, explain to patients the importance of risk reduction and empower them with strategies that will assist in this. Patients place great value on advice from their clinicians. For example, in the case of a patient with uncontrolled diabetes, indicate the need for improved glucose control. If a patient smokes, stress the importance of smoking cessation. Such recommendations go hand-in-hand with instructions in better self-care, daily oral hygiene, and improved diet (Table 2 provides a summary).

RECORD

After reviewing, reporting, and recommending, the final step is record. Oral health professionals should record patients’ positive risk factors in their charts. Recommendations on how to eliminate modifiable risk factors and manage nonmodifiable risk factors should also be documented at this time.

MODIFIABLE RISK FACTORS

As part of periodontal disease risk assessment, clinicians need to identify individuals’ modifiable risk factors. Systemic risk factors include diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, osteopenia, and low dietary intake of nutrients, such as vitamin C, D, and calcium. Behavioral risk factors include smoking, while psychosocial risk factors encompass elevated stress levels. These risk factors are amenable to change or elimination, and effective treatment strategies exist that will aid in their reduction or elimination. Information on the presence of these factors should be obtained during every clinical visit and updated at each patient clinical encounter. Thoroughness is necessary when speaking to patients about current methods for managing any of the above risk factors for periodontal diseases.

As part of periodontal disease risk assessment, clinicians need to identify individuals’ modifiable risk factors. Systemic risk factors include diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, osteopenia, and low dietary intake of nutrients, such as vitamin C, D, and calcium. Behavioral risk factors include smoking, while psychosocial risk factors encompass elevated stress levels. These risk factors are amenable to change or elimination, and effective treatment strategies exist that will aid in their reduction or elimination. Information on the presence of these factors should be obtained during every clinical visit and updated at each patient clinical encounter. Thoroughness is necessary when speaking to patients about current methods for managing any of the above risk factors for periodontal diseases.

CIGARETTE/TOBACCO CESSATION

Cigarette smoking is the most significant risk factor associated with periodontal disease incidence, severity, progression, and negative treatment outcomes. Oral health professionals have a moral obligation to engage in tobacco cessation strategies, and to encourage all patients who smoke to quit.

Among patients who smoke cigarettes or use tobacco, the most important factor in quitting is self-motivation. Recommendation by a trusted oral health professional goes a long way in helping spark motivation for change. To better help clinicians assist their patients with smoking cessation, the United States Public Health Services Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence,10 recommends the following:

- Ask all patients about tobacco

- Advise patients to quit

- Assess willingness to quit

- Assist with counseling/pharmacotherapy

- Arrange for follow-up within the first week of the quit date

Pharmacotherapy may be recommended to patients who need additional support to achieve smoking cessation. Effective adjuncts include nicotine replacement therapies, such as bupropion or varenicline. Data suggest the latter pharmacotherapy is most effective at achieving smoking cessation.11,12

DIABETES PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Diabetes and prediabetes are important risk factors for periodontal diseases. Identifying undiagnosed diabetes or prediabetes is important as interventions have been shown to reduce the development of diabetes and could potentially reduce the onset or severity of a periodontal disease.13,14 Several reports recommend screening for diabetes in the dental practice. The American Diabetes Association recommends that individuals with diabetes achieve a goal hemoglobin A1c of <7.0%. For patients with diabetes and periodontal diseases, glucose control and periodontal disease management are extremely important.15 A consensus report from the AAP and European Federation of Periodontology16 found that periodontal health plays an important role in the management of diabetes. The report outlines clinical recommendations for dental professionals to use when treating patients with diabetes and emphasizes the importance of an annual comprehensive periodontal evaluation as part of an effective diabetes management program. This consensus report is based on a large body of scientific evidence that suggests periodontal health may be helpful in controlling diabetes.16

Diabetes and prediabetes are important risk factors for periodontal diseases. Identifying undiagnosed diabetes or prediabetes is important as interventions have been shown to reduce the development of diabetes and could potentially reduce the onset or severity of a periodontal disease.13,14 Several reports recommend screening for diabetes in the dental practice. The American Diabetes Association recommends that individuals with diabetes achieve a goal hemoglobin A1c of <7.0%. For patients with diabetes and periodontal diseases, glucose control and periodontal disease management are extremely important.15 A consensus report from the AAP and European Federation of Periodontology16 found that periodontal health plays an important role in the management of diabetes. The report outlines clinical recommendations for dental professionals to use when treating patients with diabetes and emphasizes the importance of an annual comprehensive periodontal evaluation as part of an effective diabetes management program. This consensus report is based on a large body of scientific evidence that suggests periodontal health may be helpful in controlling diabetes.16

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Cardiovascular disease is associated with periodontal diseases.17 Oral health professionals should review the therapeutic regimens and medication histories of all patients with cardiovascular disease. Important goals to consider in patients with diagnosed cardiovascular disease are control of blood pressure, cholesterol, and lipids. Current guidelines for blood pressure in patients with diabetes or cardiovascular disease suggest a target of 140/80 mmHg.18 Lipid lowering therapy is another important component of cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment. In general, the goal of lipid lowering therapy is a total cholesterol <200 mg/dl and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <130 mg/dl.

OBESITY

Obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m) is an important risk factor for periodontal diseases and diabetes alike. Abdominal fat is even more closely associated with periodontal diseases, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Even modest goals to reduce caloric intake can lead to reduction in weight. Counting calories and reducing intake of high-calorie beverages are helpful in weight reduction and also reduce the risk for dental and root caries. The Mediterranean diet, which is rich in fruit and vegetable intake, has been associated with positive health parameters. For exceedingly obese individuals, bariatric surgery is an additional weight-loss alternative that may be explored.

OSTEOPOROSIS AND OSTEOPENIA

Osteoporosis is an important risk factor for periodontal bone loss, tooth loss, and implant failure.19 Management of osteoporosis includes lifestyle measures, adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, weight-bearing exercise, and prevention of falls. Adults age 50 and younger should take 1,000 mg calcium and 400 IU to 800 IU of vitamin D daily. Women between age 51 and 70 should take 1,200 mg calcium and 400 IU to 800 IU of vitamin D each day. Men age 51 to 70 are advised to take 1,000 mg calcium and 400 IU to 800 IU vitamin D per day. For men and women older than 70, 1,200 mg calcium and 800 IU vitamin D should be taken daily. Pharmacotherapy includes bone sparing agents, bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, and risedronate), and selective estrogen receptor modulators. Patients on bisphosphonate therapy should be closely monitored when an invasive dental procedure, such as oral surgery, is indicated, due to the risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Osteopenia, a reduction in bone density below the normal value for age and gender, is a risk factor for alveolar bone loss. Management of mild and moderate osteopenia includes adequate intake of calcium, vitamin D, and regular, moderate weight-bearing exercise.

ADDITIONAL LIFESTYLE FACTORS

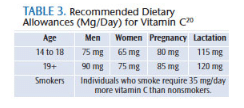

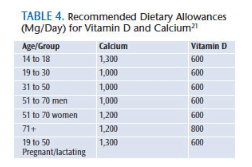

Patients should be questioned for daily intake of vitamin C, vitamin D, and calcium. Table 3 shows the recommended daily amounts for vitamin C, and Table 4 shows the recommendations for vitamin D and calcium.20,21

Excessive daily stress and poor coping strategies are risk factors for periodontal diseases, cardiovascular disease, and other conditions. As such, oral health professionals should recommend that patients experiencing high levels of stress seek professional help and implement self-help measures when possible. These include good nutrition, avoiding excess stimulants (caffeine, alcohol), daily exercise, resilience strategies, and stress-coping mechanisms. The goal is to reduce the negative physical effects of high daily stress.

GENETIC SUSCEPTIBILITY

Genetic susceptibility to periodontal diseases has been proposed in studies conducted on twins and evaluation of candidate genes.22–24 Recently, functional polymorphisms in the IL-1B gene have been found to be associated with moderate and severe periodontitis in different ethnic groups.22 Simple chairside tests are available to ascertain genetic risk factors for periodontal diseases. These tests are important new tools that can help identify high-risk patients and develop more individualized treatment plans.

SUMMARY

Oral health professionals have dedicated their careers to improving the dental health of the public. This proposed periodontal risk assessment model builds on procedures that are already part of a routine professional care appointment. The model discussed enables clinicians to help monitor and improve outcomes without the need to increase chairtime or appointment lengths. Rather, this model of risk factor monitoring and management provides dental professionals with the opportunity to improve dental and medical outcomes in the general population, especially among high-risk populations, by focusing on early identification and proactive targeted interventions. More important, it allows for individualized dental/periodontal treatment in a patient-centered holistic model, which includes dental, medical, and psychosocial care.

REFERENCES

- Genco RJ, Borgnakke WS. Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:59–94.

- Genco RJ. Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 1996;67(Suppl 10):1041–1049.

- Kinane DF, Marshall GJ. Periodontal manifestations of systemic disease. Aust Dent J. 2001;46:2–12.

- Grossi SG. Assess periodontal risk. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(10):58–62.

- Page RC, Martin JA, Loeb CF. The Oral Health Information Suite (OHIS): its use in the management of periodontal disease. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:509–520.

- Page RC, Krall EA, Martin J, Manci L, Garcia RI. Validity and accuracy of a risk calculator in predicting periodontal disease. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:569–576.

- Page RC, Martin J, Krall EA, Mancl L, Garcia R. Longitudinal validation of a risk calculator for periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:819–827.

- Lang NP, Tonetti MS. Periodontal risk assessment (PRA) in supportive periodontal therapy (SPT). Oral Health Prev Dent. 2003;1:7–16.

- American Academy of Periodontology. Gum Disease Risk Assessment Test. Available at: perio.org/consumer/riskassessment. Accessed May 21, 2014.

- Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A US Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:158–176.

- Mahmoudi M, Coleman CI, Sobieraj DM. Systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of varenicline vs bupropion for smoking cessation. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:171–182.

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:56–63.

- Corbella S, Francetti L, Taschieri S, De Siena F, Fabbro MD. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control of patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;13;4:502–509.

- Simpson TC, Needleman I, Wild SH, Moles DR, Mills EJ. Treatment of periodontal disease for glycaemic control in people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;12: CD004714.

- Borgnakke WS, Ylostalo PV, Taylor GW, Genco RJ. Effect of periodontal disease on diabetes: a systematic review of epidemiological observational studies. J Periodontol. 2013:84(Suppl 4):S135–S152.

- Chapple ILC, Genco RJ; working group 2 of the joint EFP/AAP workshop. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Periodontol. 2013;84(Suppl 4):S106–S112.

- Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, et al. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology Editors’ Consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:59–68.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:S11-S66.

- Wactawski-Wende J. Periodontal diseases and osteoporosis: association and mechanisms. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:197–208.

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

- Wu X, Offenbacher S, López NJ, et al. Association of interleukin-1 gene variations with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis in multiple ethnicities. J Periodont Res. 2014 Apr 2. Epub ahead of print.

- Hacker BM, Roberts FA. Periodontal disease pathogenesis: genetic risk factors and paradigm shift. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2005;17:97–102.

- Baker PJ, Roopenian DC. Genetic susceptibility to chronic periodontal disease. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:1157–1167.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2014;12(6):65–69.