What the Future Holds

While advancements in science and technology are transforming the face of dental hygiene practice, the patient populations seeking oral care services are also undergoing significant change.

Anniversaries are a time to reflect upon past accomplishments, but they also provide an opportunity to think about what lies ahead. Certainly, we have seen tremendous growth in the discipline of dental hygiene over the past 100 years, especially given the significant breakthroughs made in both technology and science. These advancements have helped to make our personal and professional practice lives easier, richer, and more diverse, although keeping up with these changes creates new and distinct challenges for today’s practitioners. How will these advancements influence our professional future?

THE MEDICALLY COMPLEX, AGING POPULATION

Technologic and scientific achievements have enabled people to live longer, maintain function, and lead healthier lives. Life expectancy today averages 78.7 years.1 Indeed, the number of people who now live to 100 has grown by almost 66% over the past three decades. In 2010, 82.8% of centenarians were women, as were 62% of those in their 80s and 72% of those in their 90s.2 Although people are living longer, they are doing so with more chronic diseases that impact overall health, including oral health and oral function.

Successes with pharmacotherapeutics, organ transplants, and the use of implantable devices and prosthetics enable longterm survival despite the presence of degenerative or debilitating diseases. For some, these advances extend longevity and facilitate independent living; for others, they prolong time spent in residential care facilities. These observations spark serious debates about balancing advances in medicine with maintaining quality of life. For dental hygienists, these individuals present with multiple medical issues that inevitably become more complex with time. While many of these older adults will seek care in traditional dental settings, dental hygienists must expand their access to these patients by providing services in both acute and chronic health care facilities, and through the use of mobile services for home health care. Reimbursement mechanisms and regulatory statutes must be in place to allow for this type of expanded access to care.

Successes with pharmacotherapeutics, organ transplants, and the use of implantable devices and prosthetics enable longterm survival despite the presence of degenerative or debilitating diseases. For some, these advances extend longevity and facilitate independent living; for others, they prolong time spent in residential care facilities. These observations spark serious debates about balancing advances in medicine with maintaining quality of life. For dental hygienists, these individuals present with multiple medical issues that inevitably become more complex with time. While many of these older adults will seek care in traditional dental settings, dental hygienists must expand their access to these patients by providing services in both acute and chronic health care facilities, and through the use of mobile services for home health care. Reimbursement mechanisms and regulatory statutes must be in place to allow for this type of expanded access to care.

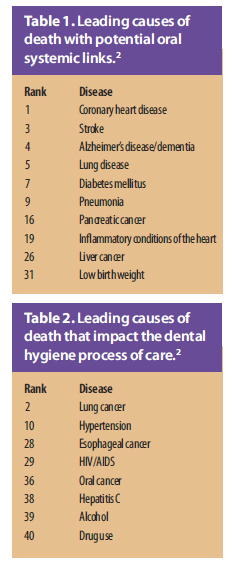

Of the top 50 causes of death in the United States, 10 are associated with potential oral systemic links,3,4 the mechanisms of which are still under investigation (Table 1). As our understanding of these relationships evolves, so too will the need for developing sound, research-supported educational, preventive, and therapeutic health strategies to reduce disease risks.

Of the top 50 causes of death in the United States, 10 are associated with potential oral systemic links,3,4 the mechanisms of which are still under investigation (Table 1). As our understanding of these relationships evolves, so too will the need for developing sound, research-supported educational, preventive, and therapeutic health strategies to reduce disease risks.

There will be an even greater need for all dental professionals to work collaboratively with other health care providers to tailor care plans to address specific patient needs. In the future, dental hygienists may train in specialties to more adequately care for targeted complex populations where oral care needs and demand for services will be high, such as geriatrics, cardiology, and oncology. Table 2 lists other causes of death that also directly impact the dental hygiene process of care.2 Hypertension is among the most common cardiovascular diseases, and given the aging of the population, dental hygienists will continue to serve as first-line responders for detecting this often silent and undiagnosed condition.

Older adults present with higher risks of cancer, infections, and infectious diseases due to past and continued use of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs.5 A growing body of research suggests that older adults, especially baby boomers, engage in recreational drug use.6 The number of adults age 50 and older with substance abuse disorders is expected to double by 2020 across all gender, race/ethnicity, and age lines.7 Drug use, especially intravenous drug abuse, is associated with the transmission of viruses, including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C. People age 50 and older represent almost one-quarter of all people with HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome in the US, although most in this age group do not get tested regularly.8 , Tobacco use is the primary risk factor for lung cancer, which remains the leading cause of all cancer-related deaths.3 Elderly smokers are more likely to die from tobacco-related illness because they have been smoking for longer periods of time and tend to be heavier smokers. Lifetime smoking contributes significantly to increased risk of chronic respiratory disease, heart disease, stroke, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease.9 Over the past 20 years, more efforts have been made to engage all dental professionals in tobacco cessation education; clearly, the need remains for greater commitment to provide this life-saving preventive intervention.

The prevalence of these conditions illustrates the ongoing need to educate dental hygienists about how to effectively help their patients reduce high-risk behaviors. Additional research must be conducted to identify which preventive health strategies are most effective to reduce behaviors leading to these and other serious health consequences.  Aging also poses additional challenges for maintaining oral health and function and quality of life. Tooth loss, neuromuscular impairments, and drug- and-disease-induced side effects directly impact food choices, eating ability, nutritional status and the ability to communicate and smile, as well as the desire to engage in social situations. Physical and cognitive impairments make performing daily oral self-care difficult. What products and devices can we develop that will make oral hygiene accessible, feasible, and effective?Given the other demands placed on nursing staff and caregivers, is it realistic to expect others to provide these oral care services to aging and/or otherwise infirm individuals, even with training? Perhaps future efforts should be aimed at positioning dental hygienists in care settings where they can directly deliver these services to the individuals who need them most.

Aging also poses additional challenges for maintaining oral health and function and quality of life. Tooth loss, neuromuscular impairments, and drug- and-disease-induced side effects directly impact food choices, eating ability, nutritional status and the ability to communicate and smile, as well as the desire to engage in social situations. Physical and cognitive impairments make performing daily oral self-care difficult. What products and devices can we develop that will make oral hygiene accessible, feasible, and effective?Given the other demands placed on nursing staff and caregivers, is it realistic to expect others to provide these oral care services to aging and/or otherwise infirm individuals, even with training? Perhaps future efforts should be aimed at positioning dental hygienists in care settings where they can directly deliver these services to the individuals who need them most.

Given projected rates of growth of the aging population over the next several decades, we must question whether we are adequately prepared to address the multifaceted needs of older adults. Organized dental and dental hygiene education has targeted efforts to increase coursework in geriatrics into the curriculum. Geriatric specialists in dentistry and dental hygiene will be needed to effectively teach future generations of providers how to safely and appropriately manage this population.

ERADICATION OF ORAL DISEASES

Despite more than 50 years of community water fluoridation and use of topical fluorides, childhood caries remains a leading infectious disease. Other risk factors, such as consumption of a cariogenic diet and poor oral hygiene, further increase the likelihood that children will develop this disease. The prevalence of caries lesions on primary teeth continues to increase, especially among those with low socioeconomic status, little education, and minority populations.10 Dental hygienists are on the front lines of caries prevention. Interestingly, there is some evidence that one-on-one dietary interventions are effective in changing behaviors related to fruit and vegetable intake and reducing alcohol use, but not as much research supports this type of intervention in decreasing sugar consumption.11 We must continue to conduct research to learn which preventive strategies are most effective at reducing risks for this disease, with the understanding that some interventions may be more effective at the individual or family level, while others should be community-based or targeted at specific populations.10

New research is focusing on novel agents to combat this pervasive disease. Data from studies of populations who consume diets that are high in polyphenol-rich foods and beverages reflect lower rates of caries. Polyphenols isolated from cranberries, raspberries, green and black tea, mushrooms, and even dark beer demonstrate inhibitory properties against a variety of oral fora, including Streptococcus mutans. These properties demonstrate potent enzyme inhibition vs bactericidal activity, which may help to prevent the development of microbial resistance with chronic exposure. Polyphenols isolated from cranberries decrease biofilm formation and inhibit acid production. These same polyphenols also inhibit the enzymes that destroy periodontal tissues in addition to providing anti-inflammatory effects. Could isolates from these food and plant sources be future agents in the fight against both caries and periodontal disease?12–14

New research is focusing on novel agents to combat this pervasive disease. Data from studies of populations who consume diets that are high in polyphenol-rich foods and beverages reflect lower rates of caries. Polyphenols isolated from cranberries, raspberries, green and black tea, mushrooms, and even dark beer demonstrate inhibitory properties against a variety of oral fora, including Streptococcus mutans. These properties demonstrate potent enzyme inhibition vs bactericidal activity, which may help to prevent the development of microbial resistance with chronic exposure. Polyphenols isolated from cranberries decrease biofilm formation and inhibit acid production. These same polyphenols also inhibit the enzymes that destroy periodontal tissues in addition to providing anti-inflammatory effects. Could isolates from these food and plant sources be future agents in the fight against both caries and periodontal disease?12–14

Plant sources are also being used in the development of recombinant proteins that may be utilized in future therapies, including vaccines and topical antibodies for the treatment of caries and HIV.15 How will these new product developments impact the availability and use of future novel interventions to combat disease? Will we finally see the development of an effective caries vaccine?16

In the most recent “Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer,” the authors report a rise in cancers associated with human papillomavirus (HPV), including an increase in the incidence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers.17 Vaccination rates with the HPV vaccine, targeted to girls for the prevention of cervical cancer, and to boys for the prevention of anogenital cancers and warts, remain low, especially among adolescent girls. Oropharyngeal cancer accounts for 78.2% of HPV-associated cancers in men and 11.6% of HPV-associated cancers in women. To date, the vaccine has not been shown to reduce rates of head and neck cancers, including oral cancer, despite the fact that the vaccine targets HPV strains 16 and 18, which are associated with oral cancer. It is too early to know what effect vaccination will have on oral cancer rates, given the novelty of the vaccine and the fact that oral cancers tend to develop more slowly and appear later in life. Researchers continue to hope that as more people become vaccinated, the rates of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers will decline.17,18 New research shows that by recommending the HPV vaccination to their patients, health care professionals can significantly impact vaccination rates, especially among women of low socioeconomic status.19 What impact will dental hygienists have on HPV vaccination rates and the future prevalence of oral cancer if they begin to increase education with their individual patients and in their community populations?

Finally, new research is exploring the use of probiotics with the intent of restoring a favorable ecosystem in the oral cavity. Early data support potential benefits for the treatment of caries and periodontal disease. Ongoing studies are investigating which strains of probiotics are efficacious against oral pathogens, with some early human trials supporting caries benefits in both children and older adults.20–22 How will probiotics be used in the future for the prevention and treatment of oral diseases?

APPLYING EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT PRACTICE

APPLYING EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT PRACTICE

The scientific advancements discussed in this article are just a sampling of the many topics that will influence dental hygiene education and practice over the next several decades. Perhaps the greatest challenge is the overwhelming task of keeping up with new developments and then translating these findings into practice. Current students and new graduates have the advantage of learning about new developments from the researchers who teach in their academic settings. Adapting our existing curriculum to make room for all of these added topics, and accommodating the necessary classroom, laboratory, and clinical coursework to include training with new technologies are significant challenges.

It is unrealistic to continue to overburden both students and faculty with an ever-growing course load within a 2-year to 3-year timeframe, especially given the well-documented “real time” hours spent in current dental hygiene programs. If we are to advance professionally and become recognized, integral members of the health care team, our academic models must reflect those of our medical peers, as well as our own commitment to professional growth.

Academic development will also influence our entry level into practice. Many health professions have increased their entry level to a master’s degree in the discipline. Still others, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology, have increased their entry level to the doctoral level. When will we finally see the credit that we have earned academically by raising our entry level to practice?

For dental hygienists in clinical practice, we are dependent on skills and training provided in school and through continuing education to locate and critically appraise ongoing research that is published in the dental hygiene and health-related literature. However, these skills are not enough to create a change in our practice behavior. We must also value what we have learned and relate it to our own clinical judgment and experiences, as well as place that information in the context of the patient populations that we treat and within our unique practice settings. This framework is the underlying basis of practicing with an evidence-based philosophy. Recognizing that clinicians often do not feel confident in their ability to locate and interpret original studies, companies are developing clinical decision software tools that sort, organize, summarize, and present best evidence obtained from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. These systems are already available in medicine, and are now in development for dentistry. The future of dental hygiene practice will be strongly supported by the use of these systems.

CONCLUSION

Given the fast rate of scientific and technological advances, dental hygienists must become better prepared to keep pace with the ever-changing rate of knowledge growth. Additional training will be required to ensure that dental hygienists are adequately prepared to treat the medically complex, aging population. Dental hygiene academic programs must evolve to accommodate the integration of new information, with a corresponding raise in the entry-level to clinical practice. Clinical practice standards must continue to evolve to reflect best practices supported by scientific research. Tools to assist with the translation and implementation of scientific evidence into our practice behavior will be essential to support dental hygiene education and practice during the coming decades.

References

- US Centers for Disease Control. Life expectancy. Death: Final Data for 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/deaths_2010_release.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2013.

- Meyer, J. Centenarians 2010: 2010 Census Special Reports. Available at: www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/reports/c2010sr-03.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2013.

- World Life Expectancy. Health Profile: United States. Available at: www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/country-health-profile/united-states. Accessed March 11, 2013.

- Genco RJ, Williams RC, eds. Periodontal Disease and Overall Health: A Clinician’s Guide. Yardly, Pa: Professional Audience Communications Inc; 2010.

- Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med. 2004;38:613–619.

- Korper SP, Raskin IE. The Impact of Substance Use and Abuse by the Elderly: The Next 20 to 30 Years. In: Korper SP, Council CL, eds. Substance Abuse by Older Adults: Estimates of Future Impact onthe Treatment System.Available at: www.oas.samhsa.gov/aging/chap1.htm. Accessed March 11, 2013.

- Han B, Gfroerer JC, Colliver JD, Penne MA. Substance use disorder among older adults in the United States in 2020. Addiction. 2009;104:88–96.

- National Institute on Aging. HIV, AIDS, and Older People. Available at: www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/hiv-aids-and-older-people. Accessed March 11, 2013.

- Fahmy V, Hatch SL, Hotopf M, Stewart R. Prevalences of illicit drug use in people aged 50 years and over from two surveys. Age Ageing. 2012;41:553–556.

- Nowak AJ. Paradigm shift: Infant oral health care—primary prevention. J Dent. 2011;39(Suppl):S49–S55.

- Harris R, Gamboa A, Dailey Y, Ashcroft A. One-to-one dietary interventions undertaken in a dental setting to change dietary behaviour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD006540.

- Bonifait L, Grenier D. Cranberry polyphenols: potential benefits for dental caries and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:a130.

- Daglia M, Papetti A, Mascherpa D, et al. Plant and fungal food components with potential activity on the development of microbial oral diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:274578.

- Yoo S, Murata RM, Duarte S. Antimicrobial traits of tea- and cranberry-derived polyphenols against Streptococcus mutans. Caries Res. 2011;45:327–335.

- Yusibov V, Streatfield SJ, Kushnir N. Clinical development of plant-produced recombinant pharmaceuticals: vaccines, antibodies and beyond. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7:313–321.

- Smith DJ. Prospects in caries vaccine development. J Dent Res. 2012;91:225–226.

- Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2009, Featuring the Burden and Trends in Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Associated Cancers andHPV Vaccination Coverage Levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:175–201.

- Nelson R. HPV cancers increase, vaccination rates remain low. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/777343. Accessed March 11, 2013.

- Wong, KY, Do, YK. Are there socioeconomic disparities in women having discussions on human papillomavirus vaccine with health care providers? BMC Womens Health. 2012;12:33.

- Anilkumar K, Monisha AL. Role of friendly bacteria in oral health – a short review. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2012;10:3–8.

- Samot J, Badet C. Antibacterial activity of probiotic candidates for oral health. Anaerobe. 2013;19:34–38.

- Twetman S, Keller MK. Probiotics for caries prevention and control. Adv Dent Res. 2012;24:98–102.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. Centennial Celebration of Dental Hygiene 1913-2013; 74-76, 78, 80, 82.