The Evolution of Dental Hygiene Education

Dental hygiene education has changed dramatically since the first class of dental hygienists graduated in 1914.

The year 2013 presents an opportunity for dental hygienists to commemorate not only the centennial anniversary of the profession, but 100 years of advancement in dental hygiene education, as well. In the early 1900s, some forward-thinking dentists shifted the focus of dentistry from surgical applications to preventive oral health care, which basically moved dentistry from treating disease to maintaining health. The oral hygiene movement gained momentum with Alfred C. Fones, DDS, who realized the need for providing preventive care and educating children about how to properly care for their teeth.1 The first dental hygienists who were educated by Fones and went to work in Bridgeport, Conn, schools produced amazing outcomes, with some schools noting caries reductions of up to 67.5%, with an average decrease in decay of 33.9% overall.

Similar to dental education, dental hygiene education’s history includes a transition from apprenticeship to formal education programs. By 1916, dental hygiene education was formalized by its establishment in institutions of higher education. One of these first formal programs—the Forsyth Training School for Dental Hygienists in Boston—still exists today. Now known as the Forsyth School of Dental Hygiene, it is part of the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.

Similar to dental education, dental hygiene education’s history includes a transition from apprenticeship to formal education programs. By 1916, dental hygiene education was formalized by its establishment in institutions of higher education. One of these first formal programs—the Forsyth Training School for Dental Hygienists in Boston—still exists today. Now known as the Forsyth School of Dental Hygiene, it is part of the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.

Dental hygiene curriculum started out as a 9-month to 1-year program of study. In 1935, high school graduation became a requirement for admission, and by 1947, dental hygiene education expanded to 2 years of formal study. In 1931, 16 dental hygiene education programs existed, and by 1935, this number had more than doubled to 34.

![]() PROFESSIONAL BENCHMARKS

PROFESSIONAL BENCHMARKS

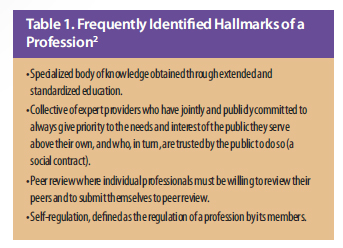

Professions must achieve certain hallmarks to cement their status (Table 1).2 Dental hygiene achieved one of those benchmarks with the establishment of a national professional organization, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA), in 1923. Dental hygiene’s first professional journal followed in 1927 with the Journal of the ADHA.1 Since then, ADHA has served as a major advocate and supporter of quality educational standards.

Licensure of dental hygienists grew from three states in 1916 to all states by 1951. Accreditation of dental hygiene education was established in 1952 through a joint effort of ADHA and the American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Dental Education (CODA). By 1955, all existing dental hygiene programs had been reviewed. In 1962, the first national board examination for dental hygienists was introduced, and by 1966, 40 licensing state boards accepted and used the exam as a requirement for licensure. Unfortunately, dental hygiene has yet to achieve the benchmarks of peer review and self-regulation.

PROLIFERATION OF 2-YEAR DEGREE PROGRAMS

The years between 1945 and 1975 have been described as the mass education era.3 The United States had emerged from World War II as the most powerful nation on earth—enjoying significant growth and prosperity.

During this period, 600 public institutions of higher learning were established; 500 were 2-year colleges. The federal government’s role in higher education included such acts as the 1963 Health Professions Educational Assistant Act, the 1963 Vocational Education Act, and the 1971 Comprehensive Health Manpower Act.

All of these were aimed at increasing manpower in the health care professions. Combined, these events greatly impacted dental hygiene education as they initiated the movement of dental hygiene programs from university-based programs to 2-year institutions. From the 1960s to the 1980s, there was a rapid expansion in dental hygiene education, resulting in 201 entry level dental hygiene programs in the US with the bulk of these programs located within 2-year community colleges. On the eve of the 21st century, 260 entry-level dental hygiene programs existed with only 54 of them residing in 4-year institutions.4 As of January 2013, there were 334 entry-level programs with still only 54 or 16% located in 4-year universities.5 A study commissioned by the ADHA in 2007 found that 60.6% of practicing dental hygienists held an associate degree as their highest level of education, yet they often graduate from 2-year institutions with coursework equivalent to 3 years or 4 years of higher education.6 CODA, which recognized the complexity of dental hygiene treatment, required expanded curricula—resulting in many associate-level dental hygiene programs requiring prerequisites equivalent to 1 year of college-level coursework. The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, identified this problem in 1939 and developed a baccalaureate degree program to accommodate the curriculum demands.

For the same reasons, ADHA adopted a policy supporting the baccalaureate degree as the minimum entry level credential for practice nearly three decades ago in 1986, yet efforts to raise the educational requirements have met with little success.

OUTSIDE INFLUENCE

The US is one of the few countries that does not have a federal ministry of education to oversee educational standards and philosophies. Education scholar Martin Trow, PhD, suggests that this lack of federal oversight allows for the influence of outside forces on American educational institutions, as opposed to being driven by academic standards alone.7 While there is much debate about whether federal oversight would be beneficial, Trow’s theory does ring true in dental hygiene education, which has been profoundly affected by forces from outside the profession. These influencers, which include factions within the dental profession, recognized the increased market demand for preventive health care services, as well as the financial gain inherent in employing additional personnel to provide these services, and thus, encouraged the move of dental hygiene educational programs to 2-year institutions, as well supported an uncontrolled growth in student enrollment. By increasing the number of dental hygienists in the workforce, the law of supply and demand automatically decreases wages. Second, the presence of less educated personnel keeps pay deflated and discourages the ability of the profession to attain more autonomy. However, the addition of degree-completion programs has helped address this problem. Dental hygienists with associate degrees who have earned more than 90 credit hours can now seek admission to degree-completion programs where they earn credits equal to an additional academic year, culminating in a baccalaureate degree.

WOMEN IN HIGHER EDUCATION

The experience of women in general is also relative to the evolution of dental hygiene education.8 Paula S. Fass, PhD, coined the term “split-work pattern of employment” to describe how decisions were made in higher education during the mid-1900s.8 Data at this time showed that college-educated women were more likely to reenter the job market in their mid-30s than those with less education, and they were much more likely to remain working into their 60s. A debate ensued about whether women’s curricula should parallel men’s, or be designed to uniquely fit women’s circumstances. Interestingly, Eunice C. Roberts, PhD, assistant dean of faculty at Indiana University, used dental hygiene as an example of a women’s curricula that established “dead-end programs, offering no basis for job advancement.” Her concern was that when dental hygienists wanted to advance their degrees in fields like biology and chemistry, they often found themselves inadmissible to graduate schools without first taking more undergraduate courses. One solution to this predicament was the establishment of graduate dental hygiene programs. In the 1960s, the first graduate programs in dental hygiene were initiated at Columbia University, University of Iowa, University of Michigan, and University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Today, there are approximately 22 master degree programs and 58 degree-completion programs that provide dental hygienists with the opportunity to advance their education and careers.

FOCUS ON RESEARCH

FOCUS ON RESEARCH

Research and scholarship aimed at improving oral health should be central to dental hygiene education. Whether it is teaching students how to access valid and reliable information or conduct original research, evidence should factor heavily into the future of dental hygiene education.9

Faculty who are actively engaged in the conduction and evaluation of research will form the backbone of evidence-based dentistry, exemplifying the characteristics of critical thinking and problem-solving that all health care professionals should possess. Faculty and students should understand the importance and benefts of research and graduate education. All dental hygienists, regardless of their practice settings and professional interests, should embrace the National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda, which provides a research infrastructure for the profession.10

Maintaining dental hygiene graduate education programs is critical to furthering this mission. Additionally, increasing the number of dental hygienists with doctoral degrees is essential to the development of researchers and scientists in the profession. The 2005 ADHA report “Focus on Advancing the Profession” recommended that a doctoral degree program in dental hygiene be created.11 Providing advanced education specific to the discipline allows for greater opportunities in advancing the art and science of the profession of dental hygiene. To date, this has not become a reality but continues to be explored.

DIVERSITY

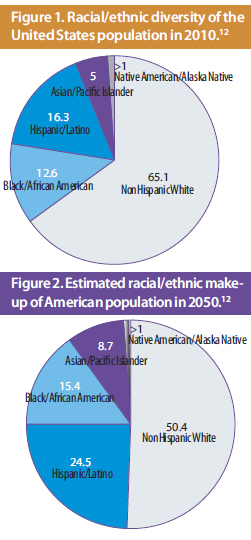

Dental hygiene was founded on the model of a female allied dental health provider. Unfortunately, very little about this model has changed over the past 100 years. In a 2007 survey of American dental hygienists, nearly 99% were women, and almost 92% were identified as nonHispanic white.6 Figure 1 illustrates the level of diversity present in the general population,12 while Figure 2 provides a glimpse of what the make-up may be in 2050.

Data show that patients often prefer to see health care providers who are of the same race.13 Dental education leaders must continue to examine and develop best practices for increasing diversity within their student bodies, as well as their faculty.

![]() FROM PUBLIC TO PRIVATE PRACTICE SETTINGS

FROM PUBLIC TO PRIVATE PRACTICE SETTINGS

The profession of dental hygiene has also transitioned from school-based public health settings to almost entirely private practice. An ADHA survey conducted in 1939 reported that the majority of dental hygienists were employed in private practice settings.1 Another survey conducted in the early 1950s found that more than two-thirds of all dental hygienists were employed in private practice. This trend continued in 1962 with more than 80% of dental hygienists working in private practice, and by 2007, 92% reported a private dental practice as their primary work site.6 Currently, significant segments of the American population do not receive any oral health care through this traditional system. An Institute of Medicine report published in 1995, “Dental Education at the Crossroads: Challenges and Change,” identified the reduction of significant disparities in oral health status and access to care as top priorities for policymakers, practitioners, and educators.9 Clearly, one of the challenges in academia is the preparation of dental hygienists to deliver quality oral health care to all segments of the US population and to be responsive to an evolving health care delivery system. The establishment of a dual-licensed dental hygienist/advanced dental therapist program at Metropolitan State University in Minneapolis, as well as the introduction of other mid-level providers, is addressing this issue.

This graduate level dental hygiene provider is trained in both preventive and therapeutic oral health care services and, through state legislation, has been awarded direct access to dental patients through a collaborative agreement with a licensed dentist.

TECHNOLOGY REVOLUTION

In many ways the foundations of dental hygiene education have remained the same through the years, with didactic instruction provided in basic and dental sciences, and clinical instruction central to the education of dental hygienists. The advancement of science, however, has resulted in the expansion of the curricula. Likewise, technology has changed the practice of dental hygiene and the education of dental hygiene students. Digital radiography, electronic patient records, cordless handpieces, and lasers are just a few examples of how technology has changed the landscape of clinical practice. The Internet, mobile technology, and dental simulators have affected the way that education is delivered, as well. In 1999, the first degree-completion program provided entirely online began at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, and in 2000, an online graduate dental hygiene program was introduced.

The ability to use technology to increase access to higher education has significantly advanced dental hygiene education. Distance education has provided the opportunity for many more dental hygienists to further their education. Roberts could not have imagined in 1997 the ability of technology to overcome her concerns about educational programs “offering no basis for job advancement.”8

CONCLUSION

The past 100 years have resulted in dental hygiene evolving in various ways. Through advanced education programs, the utilization of technology, and research and scholarship aimed at improving oral health care, dental hygienists have played an integral role in meeting the population’s oral health care needs. The introduction of new workforce models for dental hygienists is yet another opportunity to continue to further the profession. It is encouraging to see the advanced dental therapy educational program become a reality through the collaboration of a diverse group of individuals working together to increase access to oral health care services for all citizens.14 Through celebrating our accomplishments and continuing to further these efforts, dental hygiene education is positioned for another exciting 100 years.

REFERENCES

- Motley WE. History of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association: 1923-1982. Chicago: American Dental Hygienists’ Association; 1986:1–26.

- Welie JVM. Is dentistry a profession? Part 2. The hallmarks of professionalism. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004;70:599–602.

- Cohen AM. The Shaping of American Higher Education. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1998:175–290.

- American Dental Association. Survey of Allied Dental Education, 1997-98. Chicago: American Dental Association; 1998.

- American Dental Association. Search DDS/DMD Programs. Available at: www.ada.org/267.aspx. Accessed February 14, 2013.

- Wing P, Langelier MH. Survey of Dental Hygienists in the United States, 2007: Executive Summary. Rensselaer, NY: Center for Health Workforce Studies, School of Public Health, University of Albany,State University of New York; 2007.

- Trow MA. American higher education. In: Goodchild LF, Wechsler HS, eds. The History of Higher Education. 2nd ed. Needham Heights, Mass: Simon and Schuster; 1997:571–586.

- Fass PS. The female paradox: higher education for women, 1945-1963. In: Goodchild LF, Wechsler HS, eds. The History of Higher Education. 2nd ed. Needham Heights, Mass: Simon and Schuster; 1997:699–723.

- Field M. Dental Education at the Crossroads: Challenges and Changes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1995.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. National dental hygiene research agenda. Available at: www.adha.org/resources-docs/7111_National_Dental_Hygiene_ Research_Agenda.pdf.Accessed February 14, 2013.

- Focus on Advancing the Profession. Chicago: American Dental Hygienists’ Association; 2005.

- United States Census Bureau. United States Census 2010. Available at: www.census.gov/2010census/. Accessed February 14, 2013.

- Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:101–110.

- Dollins H, Bray KK, Gadbury-Amyot C. A qualitative case study of the legislative process of the hygienist-therapist bill in a large Midwestern state. J Dent Hyg. In press.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. Centennial Celebration of Dental Hygiene 1913-2013; 46-48, 50, 52, 54-55 .

PROFESSIONAL BENCHMARKS

PROFESSIONAL BENCHMARKS FROM PUBLIC TO PRIVATE PRACTICE SETTINGS

FROM PUBLIC TO PRIVATE PRACTICE SETTINGS