What Oral Health Professionals Need to Know About the AAP’s Classification System

The new system is designed to support clinicians in their ability to provide individualized, patient-centered care.

A system of classification for periodontal and peri-implant diseases allows clinicians to properly diagnose and treat individuals with periodontal and peri-implant conditions. The American Academy of Periodontology’s (AAP) 1999 classification system was based on an infection and host response model. The 1999 system recognized both dental plaque-induced gingival diseases and nonplaque-induced gingival lesions along with seven categories of periodontal diseases and conditions. These categories were chronic periodontitis, aggressive periodontitis, periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic disease, necrotizing periodontal diseases, abscesses of the periodontium, periodontitis associated with endodontic lesions, and developmental or acquired deformities and conditions.1

In 2017, the AAP revised the 1999 system to be consistent with current knowledge on pathophysiology. The updated system now aligns periodontal diagnosis in a manner similar to a medical diagnosis. The method of making a diagnosis in oncology served as a model for the new periodontal classification system.2 In oncology, the diagnosis is based on the stage of severity of the disease process, the extent and distribution of the pathologic damage, the complexity of management, and a grading that relates to the rate of disease progression and risk factors that facilitate disease progression.

Incorporating this medical model into the diagnosis of periodontitis allows for a more individualized diagnosis for each case. It takes into account the severity, extent, and distribution of the destruction of periodontal tissues and the rate of progression of disease and responsiveness to therapy. The criteria for staging includes local risk factors that add to the complexity of the disease, while grading incorporates systemic risk factors that contribute to the rate of progression of the disease. Incorporating risk factors that may confound therapy and alter the prognosis of the disease also provides clinicians with guidelines to establish an appropriate diagnosis. This helps the clinician determine whether providing periodontal therapy is beneficial or if extraction would be a more realistic approach.

By generating a more predictable prognosis, this categorization of the patient’s clinical, radiographic, and systemic health information results in a more individualized therapeutic approach to case management.

THE 2017 CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

The 2017 classification provides case definitions and identifies three forms of periodontitis. Aggressive periodontitis—previously described as bone loss associated with young patients—and chronic periodontitis—a disease process associated with adults—have been combined into one category: periodontitis.3–5 Necrotizing periodontal disease and periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic disease are the second and third categories.6,7

To individualize a diagnosis of periodontitis for each patient, the amount of clinical attachment loss is first recorded. This clinical information is supplemented with recording the pattern, extent and rate of radiographic bone loss. In addition, other factors, such as the level of plaque accumulation relative to the severity of attachment loss, smoking, and diabetes, are introduced, as they increase the risk for and rate of continued attachment loss.

STAGING

In the 2017 system, the severity is described as the stage of the disease.8 In the 1999 system, clinical attachment loss was the key metric to describe the severity of the disease process. In the new system, clinical attachment loss remains the primary factor, supplemented with radiographically determined bone loss. Staging also involves accounting for lost teeth or those that will most likely be lost due to periodontitis. Other factors involved in staging are furcation status, degree of restorative difficulty, occlusal traumatism and determination of the need for complex rehabilitation.

The stages are as follows:9

Stage I: Initial periodontitis with < 15% bone loss, no tooth loss due to periodontitis

Stage II: Moderate periodontitis with bone loss in the coronal 1⁄3 of the root; no tooth loss due to periodontitis

Stage III: Severe periodontitis with bone loss in the mid 1⁄3 of the root with the likely loss of some teeth

Stage IV: Bone loss in the apical 1⁄3 of the root and the likely loss of the remaining dentition.

EXTENT AND DISTRIBUTION OF DISEASE

Extent and distribution of disease are also incorporated into the diagnosis under staging, based on the number of teeth affected. The extent refers to the percentage of teeth involved, and distribution refers to the type of teeth involved. The system records the extent using the terms localized and generalized. Localized indicates less than 30% of the dentition is affected, and generalized indicates more than 30% of the dentition is affected. Distribution refers to the type of teeth involved. For example, the bone loss may only be associated with molars and incisors. The distribution of bone loss only affecting molars and incisors typically occurs in the disease process formally diagnosed as localized aggressive periodontitis in the 1999 classification.

GRADING

In the new system, the progression of bone loss is recorded as the grade of the disease: A: slow, B: medium, and C: rapid.

Without previous patient records, grading is determined by dividing the patient’s percentage of bone loss by his/her age. With previous radiographs, a more precise grading is determined by dividing the patient’s percentage of bone loss over the last 5 years by his/her age. Grade A is less than 0.5, Grade B ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, and Grade C is greater than 1.0.

A patient’s grading score can change over time, even with bone loss present. If after 5 years no additional bone loss occurs, the grading score could improve. This grading indicates that the patient is stable or, in medical terms, in remission. As the patient still has bone loss, the diagnosis continues to be periodontitis; however, the condition could be described as health on a reduced periodontium. Patients with a history of periodontitis always remain at risk for future periodontal destruction and should be maintained accordingly.

CLINICAL CASE-BASED REVIEW

To better understand this concept, the following case studies may be helpful. They include two men with similar probing depth measurements and a similar percentage of radiographic bone loss. Each patient presents to a new dentist for an initial visit with 5 mm to 6 mm probing depths, minimal gingival recession, and no occlusal discrepancies. Radiographic indications of generalized bone loss extending apically to the middle 1⁄3 of the root length are noted for both patients. Records indicate that both patients were compliant with a biannual recare program. Tooth mobility is not significant for either patient.

The first patient is 40, obese, and presents with type II diabetes with an average HGA1c of 8.5 over the past 3 years. He smokes ½ pack of cigarettes per day. Recent radiographs are compared to radiographs exposed 5 years ago by a previous dentist. The comparison reveals a significant change in bone levels over that time: initial bone loss of 5% increases to 40% bone loss 5 years later. The bone loss is vertical or angular in architecture. This patient’s oral hygiene is fair and he has been seen twice a year for a prophylaxis. Bleeding on probing is 50% of probed sites. The level of plaque is not commensurate with the severe level of bone loss.

The second patient is 55, in good health, has a low BMI, has fair oral hygiene, and is a former smoker. He stopped smoking at age 32. Radiographs taken 5 years ago indicate 15% bone loss. Recent radiographs indicate bone loss at 40%. Therefore the change in bone loss over the past 5 years is 35%. Radiographs indicated horizontal bone loss. Bleeding on probing is less than 10% of probed sites.

Using the previous 1999 system, both patients are classified at the initial visit with the same diagnosis: chronic periodontitis. A routine treatment plan would be generated. This would include four quadrants of scaling and root planing with a re-evaluation at 1 month. The possibility of surgery would likely have been introduced to both patients at the initial consultation.

The new system would describe the diagnosis for the first patient as periodontitis, generalized, stage III, grade C. The diagnosis includes a grade C as the rate of bone loss is determined by taking the percentage of bone loss over the past 5 years (35%) and dividing it by the patient’s age (40). The result is 0.85, which should be B grade. However the reported smoking, diabetes, and > 10% bleeding on probing as risk factors downgrade his grade to C.

This diagnostic information allows the clinician to formulate a treatment plan that not only includes phase I therapy, but also smoking cessation and a discussion of diabetes management. In terms of treatment and prognosis, the grading of his condition indicates a poor prognosis. Moreover, surgical intervention would not be recommended if the patient continues to smoke and maintain elevated blood glucose levels.

The diagnosis for the second patient would be periodontitis, generalized, stage III, grade B. Although the bone loss percentage (ie, severity) is the same as the first patient, the rate of bone loss over the past 5 years is medium. This was determined by dividing change in bone loss over the past 5 years (35%) by his age (55), which equals 0.63. This is less than 1 and greater than 0.5, therefore a grade B. There is no risk related to smoking and diabetes to downgrade this result.

A treatment plan of scaling and root planing would be indicated for the second patient’s diagnosis. If probing depths reduce to 3 mm or 4 mm post phase I therapy and the patient’s bone levels stay the same over the next 5 years, the patient will still have a diagnosis of periodontitis but his grade would change to A. This indicates the patient is stable. He now has health on a reduced periodontium; however, he must remain in maintenance care. Patients who have been treated for periodontitis must be monitored and maintained indefinitely.

The diagnosis known as aggressive periodontitis was associated with severe bone loss observed in teenagers and young adults in the 1999 classification system. No longer included in the new classification, the next case will demonstrate how to classify a patient with this clinical and radiographic appearance using the stage and grading components of the new system.

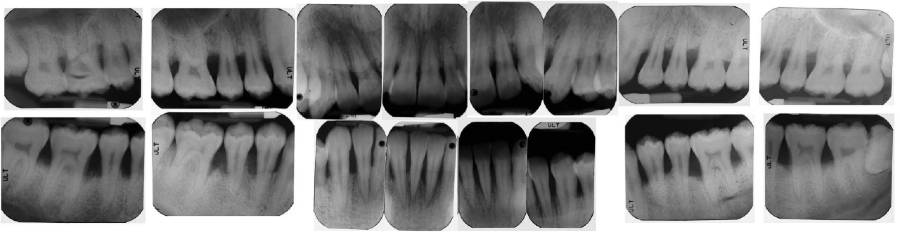

Figure 1 and Figure 2 represent clinical and radiographic findings of a 19-year-old African American man in good health with generalized 5 mm to 7 mm probing depths, fair oral hygiene, and radiographs indicating 50% bone loss. Fifty percent bone loss is severe. As previous periapical radiographs were not available, the grade was determined by dividing his bone loss of 50% by his age (19), which equals 2.63. This indicates very rapid bone loss. The diagnosis is periodontitis generalized, stage III, grade C.

A treatment plan would include scaling and root planing in conjunction with antibiotic therapy. As the disease process is severe and the rate of progression rapid, the patient would be advised that, without therapy, his prognosis likely includes tooth loss.

CLASSIFICATION FOR PERI-IMPLANT DISEASE

Peri-implant health is clinically characterized by the lack of erythema, edema, and bleeding on probing. Although probing depths greater than 3 mm are a concern around the natural dentition, defining a range of probing depths associated with peri-implant health is not possible.10

Peri-implant mucositis associated with peri-implant soft tissues is distinguished by inflammation and bleeding on probing.11 The bacterial etiology of peri-implant mucositis is the same microbiota associated with gingivitis. Similar to gingivitis, peri-implant mucositis can be reversed with good self-care and professionally provided treatment procedures that reduce biofilm.12 Another potential nonplaque induced peri-implant mucositis is subgingival cement retention. Prevention can be achieved through the use of provisional cement and thorough removal of post-crown cementation.

Peri-implantitis is a pathologic condition of the mucosal and supporting osseous tissues associated with a dental implant. Clinical findings include peri-implant mucosal inflammation accompanied by bleeding on probing, suppuration, increased probing depths and radiographic indication of bone loss around the implant fixture. Comparative radiographs will indicate progressive loss of supporting bone.

The etiology of peri-implantitis is bacterial plaque. The composition of subgingival bacteria associated with peri-implantitis is similar to the microbiota associated with periodontitis.13 Risk factors include poor plaque control, prosthetic restorations that are difficult to clean, lack of professional maintenance and history of severe periodontitis.14 Current evidence indicates that peri-implant mucositis precedes peri-implantitis. Without treatment, peri-implantitis is likely to progress resulting in implant loss. Criteria for diagnosis are: presence of bleeding and/or suppuration on gentle probing, probing depths of ≥ 6 mm and bone levels ≥ 3 mm apical to the most coronal portion of the intraosseous part of the implant.

Prevention is critical to implant health.15 The keys of success are: case selection, site preparation, cleansable prosthetic design, and recare program. When mucositis occurs, therapy must be provided to eliminate the implant-associated plaque so that mucositis can be reversed. Left untreated, mucositis may proceed to peri-implantitis.

Once the diagnosis of peri-implantitis is made, efforts should be initiated to stop the progression of disease. This may include nonsurgical therapy and subsequent surgical intervention. Presently, the literature is not completely clear on an overall process of management of progressing bone loss around implants. What has been demonstrated is that, in some circumstances, the progression of disease can be stopped and we can achieve peri-implant health around the implant.10

CONCLUSION

The AAP’s new classification system is designed to support oral health professionals in their ability to provide individualized, patient-centered care. With more specific parameters defining periodontal health and disease, as well as peri-implant problems, we are well prepared to provide the best possible care to our patients.

REFERENCES

- Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6.

- Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S159–S172.

- Papapanou PN, Sanz M, et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S173–S182.

- Needleman I, Garcia R, Gkranias N, et al. Mean annual attachment, bone level and tooth loss: a systematic review. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S120–S139.

- Fine DH, Patil AG, Loos BG. Classification and diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S103–S119.

- Billings M, Holtfreter B, Papapanou PN,Mitnik GL, Kocher T, Dye BA. Age-dependent distribution of periodontitis in two countries: findings from NHANES 2009 to 2014 and SHIP-TREND 2008 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S140–S158.

- Herrera D, Retamal-Valdes B, Alonso B, Feres M. Acute periodontal lesions (periodontal abscesses and necrotizing periodontal diseases) and endo-periodontal lesions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S85–S102.

- Albandar JM, Susin C, Hughes FJ. Manifestations of systemic diseases and conditions that affect the periodontal attachment apparatus: case definitions and diagnostic considerations. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S183–S203.

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, Chapple I, Jepsen S Kenneth S. Kornman KS, Brian L. Mealey BL, Papapanou PN, Sanz M, Tonetti MS A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S1–S8.

- Berglundh T, Armitage G, et al. Peri-implant diseases and conditions:Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S313–S318.

- Heitz-Mayfield LJA, Salvi GE. Peri-implant mucositis. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S257–S266.

- Pontoriero R1, Tonelli MP, Carnevale G, Mombelli A, Nyman SR, Lang NP. Experimentally induced peri-implant mucositis. A clinical study in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;5:254-9.

- Mombelli A, De´caillet F. The characteristics of biofilms in peri-implant disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl. 11):203–213.

- Schwarz F, Derks J, Monje A, Wang H-L. Peri-implantitis. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S267–S290.

- Jepsen S, Berglundh T, Genco R, Aass AM, Demirel K, Derks J, Figuero E, Giovannoli JL, Goldstein M, Lambert F, Ortiz-Vigon A, Polyzois I, Salvi GE, Schwarz F, Serino G, Tomasi C, Zitzmann NU. Primary prevention of peri-implantitis: managing peri-implant mucositis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(Suppl 16):S152–157.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2020;18(6):16-18,21.