PREDRAGIMAGES/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

PREDRAGIMAGES/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

What Do Lab Values Mean?

Understanding a patient’s lab values—which can impact dental treatment—is key to providing comprehensive care.

This course was published in the March 2019 issue and expires March 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss why understanding a patient’s complete blood count is important to providing safe dental care.

- Identify the oral health effects of low red blood cell count, low platelets, and low white blood cell count.

- Explain the meaning of lab results for patients with diabetes and how these impact the provision of oral health care.

- List the systemic health problems that require lab values in order to ensure the safe provision of oral health care.

At the turn of the 21st century, the United States Surgeon General, David Satcher, MD, PhD, acknowledged for the first time that oral health was an integral part of overall health.1 This statement inextricably linked oral health outcomes to systemic conditions. While this idea had been ingrained in the oral health care field for several decades, it continues to remain artificially separated from general medical care.2 Medical colleagues may not be aware of the implications of oral health on their patients’ systemic problems, therefore, dental hygienists cannot rely on medical practitioners to educate patients concerning the oral-systemic link.3

Evidence-based research has shown a relationship between oral health and many significant medical conditions, including coronary heart disease, respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, and low birth weight babies.4–7 Part of the dental hygienist’s role is to investigate potential systemic conditions that may affect dental treatment.3 Dental hygienists are responsible for regular and thorough examination and interpretation of patients’ medical histories; medication regimens, including side effects and interactions; and current oral health status. As such, dental hygienists must be comfortable reading and interpreting patient lab values in order to support and deliver safe and effective patient care that considers individual systemic factors.

Requesting lab values for patients with complex medical issues or patients who are undergoing extensive medical treatment is crucial to providing safe and effective dental care with positive outcomes. Knowing what lab information is needed from a patient’s medical team and how, in turn, those lab results affect dental health or treatment can be confusing. What’s more, collaboration with a patient’s nurse, nurse practitioner, or physician can sometimes elicit more questions than answers. Clear and concise explanations of the dental treatment planned and concerns regarding patients’ current health status must be communicated, so that the medical team can give appropriate recommendations to ensure patient safety.

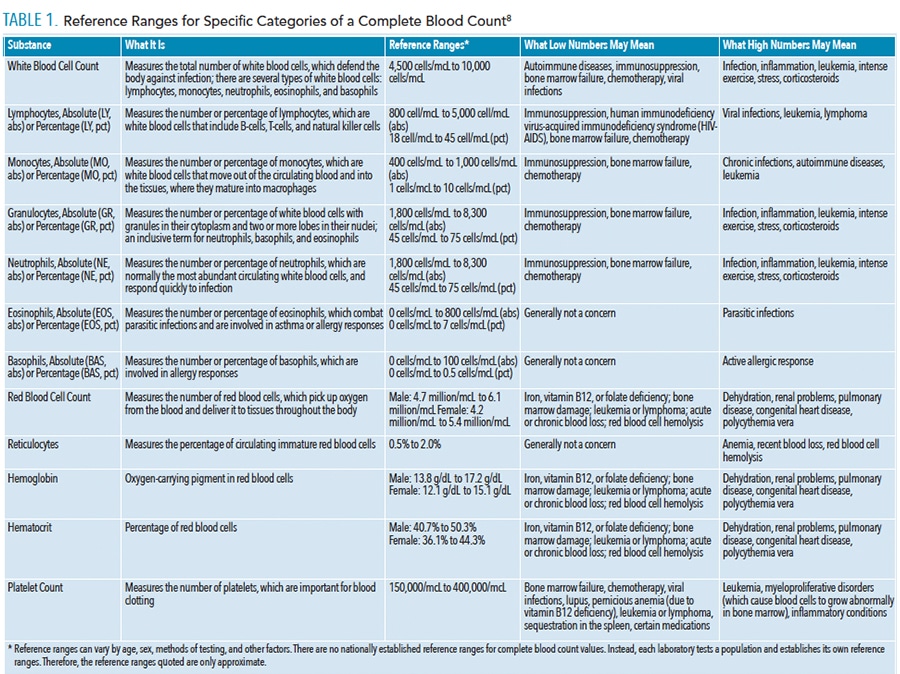

The most general blood work consists of a complete blood count, which reflects a patient’s current blood cell levels and can help identify any blood abnormalities. Complete blood count with differential further breaks down the blood cell values and provides a clearer picture of any deficiencies that may affect dental treatment. Table 1 lists reference ranges for specific categories of a complete blood count with a differential lab test and how values outside of the reference range may indicate disease.8

LOW BLOOD CELL COUNT

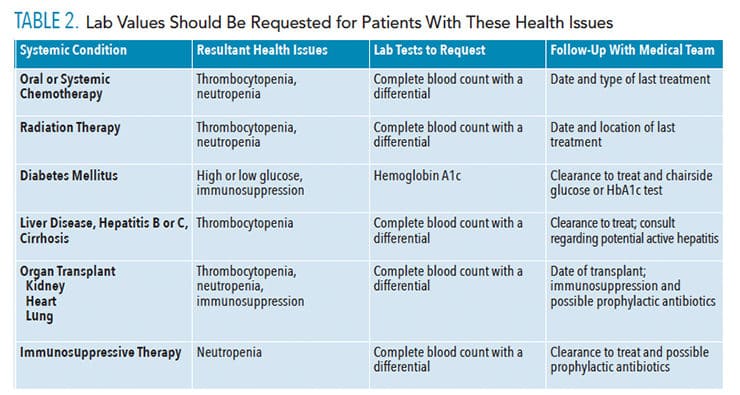

While not routinely requested for dental treatment, a review of recent lab results are appropriate if the medical history indicates medically compromised conditions. Table 2 lists the conditions that may require such a review. Abnormally low red blood cell and hematocrit counts (anemia) may contribute to poor wound healing. Consideration of this risk should be addressed before beginning nonsurgical periodontal therapy. For these patients, the use of periodontal medicaments may assist with healing and reduce infection risk.

PLATELETS

Platelets are critical for blood clotting. If platelet numbers are low, there is an increased risk for excessive bleeding and a potentially dangerous situation in the dental chair. When performing nonsurgical periodontal therapy on a patient with abnormally low platelet levels (thrombocytopenia), topical hemostatic agents can be used to help control bleeding.

WHITE BLOOD CELLS

White blood cell counts, or more specifically neutrophil values, provide information on a patient’s risk for infection. Patients with a compromised immune system—from cancer therapy, organ transplant, or human immunodeficiency virus—are at risk for opportunistic infections and may have delayed wound healing. These patients require evaluation for bacterial, fungal, and viral infections and need to be judiciously screened for oral cancer. Complete blood count with a differential provides further details on white blood cell counts, including neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and basophils. In particular, specific knowledge of a patient’s acute neutrophil count can help medical and dental providers to better evaluate a patient’s immune health and his or her ability to fight infection or recover from invasive treatment.9

Diabetes Mellitus

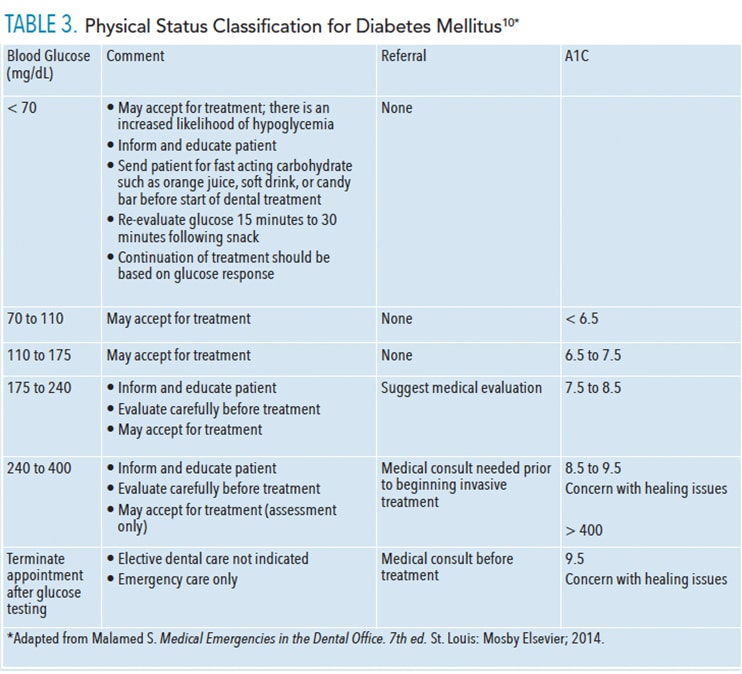

Poorly controlled type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus may also interfere with wound healing and patient safety during treatment. Chairside glucose test can give a snapshot of the patient’s real-time status, and is important for assessing risk of acute emergency in the dental setting. Hemoglobin A1c can also be tested chairside and will give a better determination of overall glucose control. Hemoglobin A1c provides a better picture of immune function, wound healing, and procedure tolerance. Table 3 (page 40) provides guidelines for evaluating glucose and HbA1c levels.10 For patients with type 1 diabetes, chairside testing is recommended prior to the initiation of invasive treatment such as nonsurgical periodontal debridement or extraction. General glucose testing for diabetic control is indicated for patients who exhibit an active periodontal disease, slow wound healing, or other opportunistic infections.10

SYSTEMIC HEALTH PROBLEMS

The most common systemic health issues that may put patients at risk for infection or bleeding are listed in Table 2. Prior to the initiation of treatment, oral health professionals should request lab values for patients who are under a physician’s care for any of the health issues listed in Table 2 to ensure their safety.

Patients with neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count values < 2.0) may require premedication prior to dental treatment to prevent sepsis.9,11,12 The decision for perioperative antibiotic coverage needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis in conjunction with the patient’s physician. Antibiotic coverage for dental procedures with absolute neutrophil count < 2.0 and deferral of treatment if absolute neutrophil count < 1.0 may be necessary.12 Patients with neutropenia are at increased risk for periodontal diseases and odontogenic infections, therefore, prompt and regular professional oral care is imperative. Subclinical or opportunistic oral infections may further weaken an already compromised immune system.9

Normal platelet counts can range from 150,000/μL to 440,000/μL. Thrombocytopenia, or platelet counts < 50,000/μL, increase patients’ risk for excessive or uncontrolled bleeding during dental procedures or post-operatively.9,13 Most invasive surgical procedures can be carried out safely with a platelet count above 50,000/μL, if there are no other confounding coagulation deficiencies.14,15 Patients with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis may have extremely low platelet counts. Consultation with the supervising physician and lab tests to evaluate platelet counts help determine the need for collaboration with the patient’s medical team. Treatment may include infusions of platelets or fresh frozen plasma before or after dental surgery to aid with clotting.15,16

CONCLUSION

The American Dental Hygienists’ Association Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice state that dental hygienists are responsible and accountable for the assessment of data collected during the appointment. Careful review of a patient’s medical history—including requesting lab work and/or medical consultations to ensure safe and effective care—is part of the dental hygiene process of care.17 Dental hygienists should evaluate and consult with the dentist or other health care providers to provide patient-centered comprehensive care. By knowing the type of lab tests to request and what the lab values may indicate about the patient’s ability to tolerate treatment, oral health professionals are better prepared to serve medically complex patients safely and confidently.

Interprofessional care and communication are paramount to the effective treatment and safety of the public. By properly addressing the oral-systemic link and ensuring safe treatment, the dental and medical communities can work together to improve the population’s health and reduce health disparities among high-risk populations.18,19

REFERENCES

- Oral Health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2000;28:685–695.

- Institute of Medicine. Advancing Oral Health in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

- Fried J. Interprofessional collaboration: If not now, when? J Dent Hyg. 2013;87:Suppl:41–43.

- Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1465–1482.

- Needleman I, Hirsch N. Oral health and respiratory diseases. Evid Based Dent. 2007;8:116.

- Graziani F, Gennai S, Solini A, Petrini M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic observational evidence on the effect of periodontitis on diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:167–187.

- Kumari P, Mendiratta S, Sharma S, Popli S. Prevalence and relationship between maternal periodontal disease and preterm low birth weight baby. J Fetal Med. 2016;3:85–91.

- Blood Test Results: CBC Explained. Available at: iwmf.com/ sites/ default/ files/ docs/ bloodcharts_ cbc(1).pdf. Accessed February 19, 2019.

- Zimmermann C, Meurer M, Grando L, Gonzaga Del Moral J, da Silva Rath I, Tarvares S. Dental treatment in patient with leukemia. J Oncol. 2015;2015:1–14.

- Malamed S. Medical Emergencies in the Dental Office. 7th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2014.

- Palmason S, Marty FM, Treister NS. How do we manage oral infections in allogeneic stem cell transplantation and other severely immunocompromised patients? Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2011;23:579.

- Fillmore WJ, Leavitt BD, Arce K, Dental extraction in the neutropenic patient. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:2386–2393.

- Exodontia Info. Post-Op Instructions for Patient on Medications Affecting Blood Clotting. Available at: http:/ / exodontia.info/ Bleeders_ Post-Op_ Instructions.html Accessed February 19, 2019.

- Joint Professional Advisory Committee. Transfusion in Surgery. Available at: transfusionguidelines.org/ transfusion-handbook/ 7-effective-transfusion-in-surgery-and-critical-care/ 7-1-transfusion-in-surgery/ . Accessed February 19, 2019.

- Cocero N, Bezzi M, Martini S, Carossa S. Oral surgical treatment of patient with chronic liver disease: assessment of bleeding and its relationship with thrombocytopenia and blood coagulation parameters. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75:28–34.

- Bansai N, Jindal M, Gupta ND, Shukla P. Clinical guidelines for periodontal management of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: current considerations. Int J Oral Health Sci. 2017;7:30–34.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/ resources-docs/ 2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2019.

- Braun PA, Cusick A. Collaboration between medical providers and dental hygienists in pediatric health care. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2016;16:59–67.

- Parker J, Dolce M. Defining the dental hygienist’s role in improving population health through interprofessional collaboration. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91:4–5.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2019;17(3):37–40.

This is an excellent article! The highlight of treating patients living with HIV in a Ryan White Clinic was the ability to access their entire blood work. We required it every 3 months! It gave me the skills to interpret a whole-istic view of my patient’s health. This should be the standard of care for all patients that have a chronic disease!