Unscrambling the Periodontitis-Diabetes Connection

A large body of evidence demonstrates that diabetes mellitus and periodontitis are closely linked but the association remains complex.

This course was published in the June 2015 issue and expires June 30, 2018. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the association between diabetes mellitus and periodontitis.

- Explain the mechanisms involved in the interactions between the two conditions.

- Identify the implications for management of dental patients with diabetes.

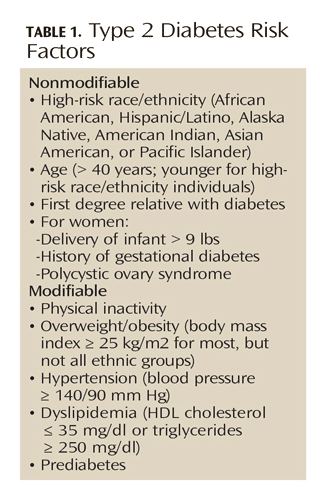

Data from the International Diabetes Federation suggest that approximately 382 million people are affected by diabetes worldwide and that the prevalence has been increasing every year in most countries.1 About 46% of individuals affected by diabetes in the world today remain undiagnosed. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 29.1 million individuals are affected by diabetes in the US.2 Although the percentage of those who remain undiagnosed in the US is—at 28% —lower than the worldwide percentage, it is still significant.3

Prediabetes is an intermediate metabolic state characterized by mild hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. Prediabetes places people at increased risk for type 2 diabetes and vascular disease.4,5 Several large multicenter clinical trials have demonstrated that timely intervention among individuals with prediabetes can return glucose levels to normal range.6,7

Diabetes has many commonalities with periodontitis. Both are prevalent, chronic diseases that often remain undiagnosed. They both disproportionately affect similar segments of the population. Finally, successful outcomes in both conditions depend heavily on intensive interventions, lifestyle modifications, and life-long maintenance. Oral health professionals are thus uniquely positioned to understand the challenges faced by patients with diabetes.

Diabetes has many commonalities with periodontitis. Both are prevalent, chronic diseases that often remain undiagnosed. They both disproportionately affect similar segments of the population. Finally, successful outcomes in both conditions depend heavily on intensive interventions, lifestyle modifications, and life-long maintenance. Oral health professionals are thus uniquely positioned to understand the challenges faced by patients with diabetes.

Diabetes is a well-established risk factor for periodontitis. The adverse effects of diabetes on periodontal status have been extensively studied,8-10 and the consensus is that the relative risk for periodontitis in patients with diabetes is approximately three-fold that of patients without diabetes. Diabetes can increase the prevalence, but also the severity and progression of periodontitis. Studies also suggest that the severity of periodontitis and response to periodontal therapy in patients with diabetes depends on the patient’s level of glycemic control, presence of other complications, and how long the individual has had diabetes.

Children and adolescents with diabetes had significantly increased gingival inflammation and attachment loss compared to controls.11,12 Regression analyses revealed statistically significant differences in periodontal destruction between cases and controls across different periodontal disease definitions tested, and the effect of diabetes on periodontal destruction remained significant among children age 6 to 11 and 12 to 18. Further, regression analysis of children with diabetes demonstrated a strong positive association between mean hemoglobin A1c (a measure of long-term glucose control) over a 2-year period and periodontitis.13

Studies show that periodontal microbiota are mostly unaltered by diabetes.14 However, emerging techniques and the ability to study the whole microbiome may provide a different perspective in the future.

Hyperglycemia amplifies the host response to bacterial challenges by promoting a series of pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant changes.10,14 The exact mechanistic pathways involved are not fully understood. Hyperglycemia drives the formation and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and leads to increased expression and activation of their chief receptor (RAGE). AGEs directly, and via their interaction with RAGE, can negatively affect cellular phenotype and function, leading to enhanced inflammation, oxidative stress, and compromised tissue repair. Hyperglycemia also directly promotes oxidative stress, and both inflammation and oxidative stress can contribute to further AGE formation. These pathways appear to perpetuate a vicious cycle of inflammatory stress in the diabetic periodontium. As normal reparatory mechanisms are impaired, the net result is accelerated periodontal tissue destruction. Importantly, these pathogenic mechanisms appear similar to those that underlie the development of other complications in diabetes.

Periodontal infections can adversely impact health outcomes in individuals with diabetes, as well.10,15 In cross-sectional studies, periodontitis in subjects with diabetes was associated with the risk for retinopathy, neuropathic foot ulceration, and subclinical heart disease. In a large, longitudinal study of subjects with type 2 diabetes, self-reported presence of fewer teeth and complete edentulism was related to an increased risk of death from all causes, cardiovascular disease (CVD)-associated death, and nonCVD-associated death.16 In other longitudinal observational studies, severe periodontitis increased the risk of poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetes, was associated with a higher prevalence of proteinuria and CVD complications in type 1 diabetes, predicted cardio/renal disease-related mortality in type 2 diabetes, and predicted overt nephropathy and stage 5 renal disease in type 2 diabetes.17–20 Periodontitis also may predict development of type 2 diabetes in previously healthy individuals.21,22

Systematic reviews of available randomized clinical trials (RCTs) demonstrated a modest, but statistically significant effect of periodontal therapy on HbA1c reduction in diabetes.23–25 However, a recent multicenter randomized controlled trial of 514 subjects with type 2 diabetes and moderate to severe periodontitis who were randomized to scaling/root planing (test group), or delayed treatment (untreated control group) did not support this finding.26 The investigators concluded that periodontal therapy did not have a significant effect on levels of HbA1c at 3 months or 6 months. The study has been criticized, with some suggesting that periodontitis was not comprehensively treated and that patients started off with relatively good glycemic control and were mostly obese—all factors that may have limited the effects of periodontal treatment. A recent editorial in support of this trial stressed that the study population was actually representative of the general US population and of what would be expected in terms of metabolic changes following standard periodontal therapy.27

Finding the answer to the question of whether periodontal treatment can affect diabetes outcomes is no simple task. The interaction between these two multifactorial chronic diseases is complex, and issues related to the timing of the periodontal intervention and/or the control of other contributory factors may come into play. It is important to note that RCTs are not meant to be “proof-of-principle” studies. Rather, they ask a specific question in a study population, with the goal to ultimately inform public health policy.

Finding the answer to the question of whether periodontal treatment can affect diabetes outcomes is no simple task. The interaction between these two multifactorial chronic diseases is complex, and issues related to the timing of the periodontal intervention and/or the control of other contributory factors may come into play. It is important to note that RCTs are not meant to be “proof-of-principle” studies. Rather, they ask a specific question in a study population, with the goal to ultimately inform public health policy.

Inflammation contributes to enhanced insulin resistance and poor glycemic control and is critically involved in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its complications.28 Further, a number of studies have demonstrated that periodontal bacteria and locally produced inflammatory mediators in individuals with periodontitis are shed into the circulation and, as a result, increase systemic inflammation.29 Thus, inflammation appears to be the key underlying mechanism. Treatment of periodontitis, at least in individuals without diabetes, also appears to have the potential to lower levels of systemic inflammatory mediators30 and may improve insulin sensitivity and glycemic control in diabetes.

UNDIAGNOSED PATIENTS

The importance of early identification of those who are affected by diabetes and remain undiagnosed cannot be overstated, as an overwhelming body of evidence has demonstrated that type 2 diabetes is preventable and that early identification and treatment can limit the disease’s life-threatening complications.31–34

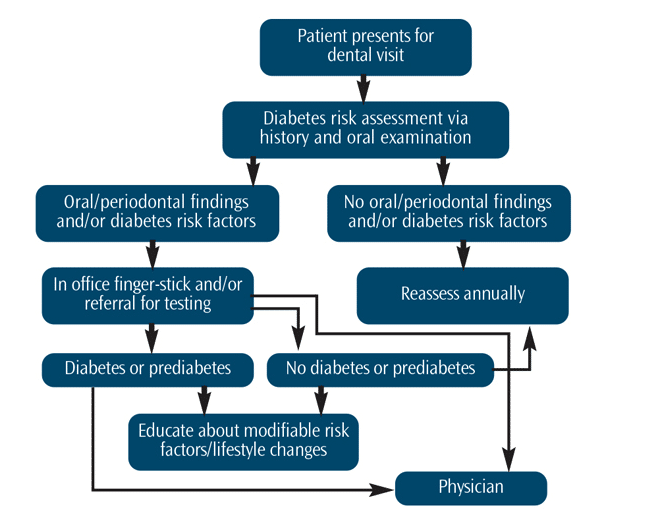

Periodontitis appears to manifest relatively early in individuals with diabetes and, in recent years, studies have assessed whether dental settings may offer a contact point where previously unrecognized dysglycemia can be identified.35–38 In these studies, simple algorithms that use easily identifiable risk factors and oral findings were shown to correctly identify the majority of unrecognized diabetes/prediabetes cases. As expected, the addition of a chairside HbA1c blood test further increased correct identification of cases. Subsequent studies showed that implementation of diabetes screening in dental practices is feasible and that most patients and oral health professionals believe that the dental visit is a good opportunity for early diabetes identification.39,40

Thus, a two-stage identification approach5 could be proposed for dental professionals (Figure 1). First, periodontal findings are considered in patients who present with other easily identifiable risk factors. In those patients with an increased risk, a point-of-care blood test can be applied. In any case, dental patients at-risk for diabetes should be informed about their risk factors and referred to a physician for further evaluation and treatment.

A challenge with diabetes identification in dental settings is the need for patients to follow-up with their physicians for a definitive diagnosis and initiation of therapy. Evidence has suggested that prediabetes identification warrants patient education regarding modifiable risk factors and lifestyle changes.3 In a pilot study, an approach to improving outcomes was assessed in dental patients who presented with diabetes risk factors and previously unrecognized hyperglycemia.41 Specifically, 101 subjects identified with potential diabetes or prediabetes were randomized into two interventions. In the control intervention, subjects were informed about their risk and advised to see a physician for further evaluation. In the test intervention, patients received a detailed explanation of their risk factors, were given a written report for the physician, and were contacted at 2 months and 4 months to inquire whether medical follow-up had occurred and to reiterate its importance. Seventy-three participants returned for the 6-month re-evaluation visit. The two intervention groups did not significantly differ. Overall, 84% of subjects reported having visited a physician and 49% reported at least one positive lifestyle change as a result of the intervention. In those identified with potential diabetes, HbA1c was significantly reduced compared to baseline. These findings suggest that diabetes risk assessment and education by dental professionals may contribute to improved outcomes.

PARTNERING FOR OPTIMAL CARE

Diabetes care must be team-based and patient-centered. Studies have reported that individuals with diabetes are less likely to visit a dentist in a given year than the controls and that the leading reason for not seeing a dentist is “lack of perceived need.”42 Further, only a fraction of patients with diabetes are aware of their increased risk for periodontitis.43–45 Raising awareness is, therefore, important, and every health professional can contribute.46

Medical professionals can raise awareness by discussing oral health and its importance to overall health with their patients and by advising patients with diabetes to seek regular dental care. As part of their initial evaluation by a physician, all patients with diabetes should be referred for a comprehensive oral/periodontal evaluation. Subsequent periodontal examinations should occur annually as part of diabetes management. For children with diabetes, annual oral screening for periodontal changes is recommended starting at age 6. Medical professionals can also briefly screen their patients with diabetes for oral and periodontal changes. They can ask about symptoms, such as sore, bleeding gums; sensitive or loose teeth; or bad taste or smell in the mouth. They can perform a quick visual assessment of the mouth for signs of food debris or plaque around teeth, red, swollen, receding or bleeding gingiva, loose teeth, separation of teeth, missing teeth, and abscesses.

Patients with diabetes should be informed by all health care providers that they are at increased risk for periodontitis. If they have periodontitis, glycemic control may be more difficult and they are at higher risk for complications. The importance of good oral and overall health behaviors should be emphasized. Points to include are good control of glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels; an effort to maintain a healthy lifestyle (healthy diet, exercise, and good oral hygiene); and, finally, the need for regular professional check-ups.

As dental hygienists are intimately involved in dental patients’ periodontal care, as well as in oral disease prevention and oral health education, they have the unique opportunity to provide diabetes risk assessment, communicate risk information, and offer health education.

REFERENCES

- International Diabetes Federation. International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Available at: idf.org/diabetesatlas/introduction/summary. Accessed: March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

- Inzucchi SE. Diagnosis of diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:542–550.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The prevalence of retinopathy in impaired glucose tolerance and recent-onset diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabet Med. 2007;24:137–144.

- Tabak AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379:2279–2290.

- Yamaoka K, Tango T. Efficacy of lifestyle education to prevent type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2780–2786.

- Jeon CY, Lokken RP, Hu FB, van Dam RM. Physical activity of moderate intensity and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:744–752.

- Lamster IB, Lalla E, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW. The relationship between oral health and diabetes mellitus. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(Suppl):19S–24S.

- Mealey BL, Rose LF. Diabetes mellitus and inflammatory periodontal diseases. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes.2008;15:135–141.

- Lalla E, Papapanou PN. Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: a tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:738–748.

- Lalla E, Cheng B, Lal S, et al. Periodontal changes in children and adolescents with diabetes: a casecontrol study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:295–299.

- Lalla E, Cheng B, Lal S, et al. Diabetes mellitus promotes periodontal destruction in children. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:294–298.

- Lalla E, Cheng B, Lal S, et al. Diabetes-related parameters and periodontal conditions in children. J Periodontal Res.2007;42:345–349.

- Taylor JJ, Preshaw PM, Lalla E. A review of the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl 14):S113–134.

- Borgnakke WS, Ylostalo PV, Taylor GW, Genco RJ. Effect of periodontal disease on diabetes: systematic review of epidemiologic observational evidence. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl 14):S135–152.

- Li Q, Chalmers J, Czernichow S, et al. Oral disease and subsequent cardiovascular disease in people with type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study based on the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified-Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2320–2327.

- Taylor GW, Burt BA, Becker MP, et al. Severe periodontitis and risk for poor glycemic control in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1085–1093.

- Thorstensson H, Kuylenstierna J, Hugoson A. Medical status and complications in relation to periodontal disease experience in insulin-dependent diabetics. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:194–202.

- Saremi A, Nelson RG, Tulloch-Reid M, et al. Periodontal disease and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:27–32.

- Shultis WA, Weil EJ, Looker HC, et al. Effect of periodontitis on overt nephropathy and end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:306–311.

- Demmer RT, Jacobs DR, Jr., Desvarieux M. Periodontal disease and incident type 2 diabetes: results from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and its epidemiologic follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1373–1379.

- Ide R, Hoshuyama T, Wilson D, Takahashi K, Higashi T. Periodontal Disease and Incident Diabetes: a Seven-year Study. J Dent Res. 2011;90:41–46.

- Simpson TC, Needleman I, Wild SH, Moles DR, Mills EJ. Treatment of periodontal disease for glycaemic control in people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD004714.

- Teeuw WJ, Gerdes VE, Loos BG. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control of diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:421–427.

- Engebretson S, Kocher T. Evidence that periodontal treatment improves diabetes outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2013;84:S153–169.

- Engebretson SP, Hyman LG, Michalowicz BS, et al. The effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy on hemoglobin A1c levels in persons with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2523–2532.

- Pihlstrom BL, Buse JB. Diabetes and periodontal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:1208–1210.

- Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:98–107.

- Loos BG. Systemic markers of inflammation in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2106–2115.

- Paraskevas S, Huizinga JD, Loos BG. A systematic review and meta-analyses on C-reactive protein in relation to periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:277–290.

- The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986.

- Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–853.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403.

- American Diabetes Association Position Statement. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care.2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–S80.

- Lalla E, Kunzel C, Burkett S, Cheng B, Lamster IB. Identification of unrecognized diabetes and pre-diabetes in a dental setting. J Dent Res. 2011;90:855–860.

- Lalla E, Cheng B, Kunzel C, Burkett S, Lamster IB. Dental findings and identification of undiagnosed hyperglycemia. J Dent Res. 2013;92:888–892.

- Genco RJ, Schifferle RE, Dunford RG, Falkner KL, Hsu WC, Balukjian J. Screening for diabetes mellitus in dental practices: a field trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:57–64.

- Bossart M, Calley KH, Gurenlian JR, Mason B, Ferguson RE, Peterson T. A pilot study of an HbA1c chairside screening protocol for diabetes in patients with chronic periodontitis: the dental hygienist’s role. Int J Dent Hyg. 2015 Mar 23. Epub ahead of print.

- Barasch A, Safford MM, Qvist V, Palmore R, Gesko D, Gilbert GH. Random blood glucose testing in dental practice: a community-based feasibility study from The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:262–269.

- Rosedale M, Strauss S. Diabetes screening at the periodontal visit: patient and provider experiences with two screening approaches. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10:250–258.

- Lalla E, Cheng B, Kunzel C, Burkett S, Ferraro A, Lamster IB. Six-month outcomes in dental patients identified with hyperglycaemia: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:228–235.

- Tomar SL, Lester A. Dental and other health care visits among U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1505–1510.

- Moore PA, Orchard T, Guggenheimer J, Weyant RJ. Diabetes and oral health promotion: a survey of disease prevention behaviors. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:1333–1341.

- Sandberg GE, Sundberg HE, Wikblad KF. A controlled study of oral self-care and self-perceived oral health in type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:28–33.

- Allen EM, Ziada HM, O’Halloran D, Clerehugh V, Allen PF. Attitudes, awareness and oral healthrelated quality of life in patients with diabetes. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:218–223.

- Chapple IL, Genco R, Working group 2 of joint EFP-AAP. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40 Suppl 14:S106–112.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2015;13(6):55–59.